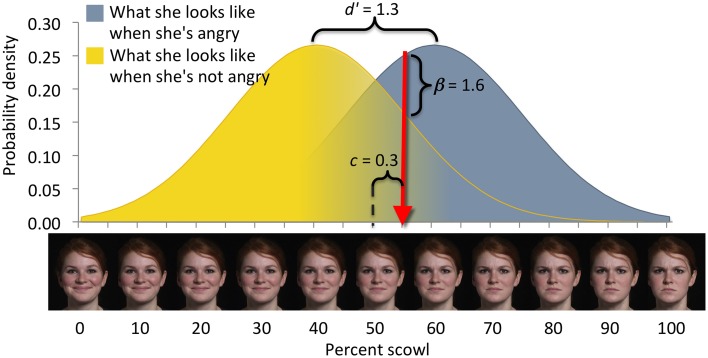

Figure 4.

Elements of the signals framework (after Lynn and Barrett, 2014). In emotion perception, for example, facial expressions are evaluated by one person (the perceiver) to determine the emotional state of another person (the sender). Signals, depicted on the x-axis, comprise two categories: targets (defining, e.g., what the sender looks like when she is angry) and foils (defining, e.g., what the sender looks like when she is not angry). Signals from either category vary over a perceptual domain such as “scowl intensity.” Any signal (i.e., a particular scowl intensity) can arise from either category, with a likelihood given by the target and foil distributions. Perceivers therefore, experience uncertainty about the category membership of any particular signal. Here, the perceiver responds to facial expressions to the right of criterion (red arrow) as if they were angry, and to facial expressions to the left of criterion as if they were not angry. Perceivers make a decision between two options and the perceptual uncertainty yields four possible outcomes: (1) Classifying a stimulus as a target when it is a target is a correct detection. (2) Classifying a stimulus as a target when it is a foil is a false alarm. (3) Classifying a stimulus as a foil when it is a target is a missed detection. (4) Classifying a stimulus as a foil when it is a foil is a correct rejection. Measures of sensitivity (e.g., d') characterize perceptual uncertainty, depicted here as overlap of the target and foil distributions. Measures of bias (e.g., c or beta) characterize the decision criterion's location in the perceptual domain. Sensitivity and bias are derived from the numbers of correct detections and false alarms committed over a series of decisions (Macmillan and Creelman, 2005). Perceptual uncertainty causes the perceiver to make mistakes regardless of his or her degree of bias; missed detections cannot be reduced without increasing false alarms.