Key Points

We report the first dedicated prospective study in HIV-Burkitt lymphoma demonstrating safety and efficacy in a multi-institutional setting.

We offer a new therapeutic option by modifying an existing regimen and making it much less toxic.

Abstract

The toxicity of dose-intensive regimens used for Burkitt lymphoma prompted modification of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC) for HIV-positive patients. We added rituximab, reduced and/or rescheduled cyclophosphamide and methotrexate, capped vincristine, and used combination intrathecal chemotherapy. Antibiotic prophylaxis and growth factor support were required; highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was discretionary. Thirteen AIDS Malignancy Consortium centers enrolled 34 patients from 2007 to 2010. Median age was 42 years (range, 19-55 years), 32 of 34 patients were high risk, 74% had stage III to IV BL and CD4 count of 195 cells per μL (range, 0-721 cells per μL), and 5 patients (15%) had CD4 <100 cells per μL. Twenty-six patients were receiving HAART; viral load was <100 copies per mL in 12 patients. Twenty-seven patients had at least one grade 3 to 5 toxicity, including 20 hematologic, 14 infectious, and 6 metabolic. None had grade 3 to 4 mucositis. Five patients did not complete treatments because of adverse events. Eleven patients died, including 1 treatment-related and 8 disease-related deaths. The 1-year progression-free survival was 69% (95% confidence interval [CI], 51%-82%) and overall survival was 72% (95% CI, 53%-84%); 2-year overall survival was 69% (95% CI, 50%-82%). Modifications of the CODOX-M/IVAC regimen resulted in a grade 3 to 4 toxicity rate of 79%, which was lower than that in the parent regimen (100%), without grade 3 to 4 mucositis. Despite a 68% protocol completion rate, the 1-year survival rate compares favorably with 2 studies that excluded HIV-positive patients. This trial was registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00392834.

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is an aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) characterized by obligate MYC gene expression driving a nearly 100% growth phase fraction. BL accounts for 1% to 2% of adult NHL but is more common in children and adolescents. Most patients present with advanced disease involving multiple extranodal sites. Historically, BL was one of the first cancers to respond to chemotherapy,1 but early relapses occurred, often in the central nervous system (CNS) with rapid disease progression.2 Cure rates of 50% to 60% were achieved in early-stage patients with high-dose cyclophosphamide, antimetabolites, and prophylactic intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy. However, only 20% of patients with bone marrow or CNS involvement achieved durable responses.3-5 In 1996, Magrath et al6 reported a 92% 2-year event-free survival (EFS) rate in HIV-negative adult and pediatric patients after intensive chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC). Results were particularly impressive in patients with bone marrow and/or CNS involvement, with an 80% 2-year disease-free survival rate. Although inferior to the Magrath report, an international multicenter phase 2 study demonstrated a 2-year EFS of 65% and 2-year overall cure rate of 72.8%, with excellent results even in high-risk patients stratified by the International Prognostic Index.6,7 Other regimens that incorporate high-dose cytarabine and methotrexate and intensive IT prophylaxis have also been similarly successful.8,9

In contrast to BL in the general population, BL comprised 25% to 40% of HIV-associated NHL before the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).10-12 BL was more recently estimated at 10%, although this study included 31% NHL unspecified.13 Patients with HIV-BL closely resemble the general BL population in terms of stage, marrow involvement (33% to 35%), CNS involvement (17% to 19%),14 and histology.15 Prior to HAART, combination chemotherapy was less successful for patients with HIV-associated NHL than for HIV-negative patients with similar NHL histopathology. Early deaths were often the result of opportunistic infection.16 However, improved immune function in the HAART era has led to a reevaluation of full-dose chemotherapy. Moreover, HIV-positive patients with BL and preserved immune function may benefit from more aggressive chemotherapeutic approaches with acceptable toxicities.3 Finally, retrospective analyses suggest that HAART era HIV-positive BL patients do poorly with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) –like regimens,17 but may do well with intensive regimens.18 Nonetheless, because of the perceived risk of increased hematologic and infectious complications, many patients with HIV-associated BL continue to be treated with CHOP and other moderate-dose chemotherapy despite inferiority in HIV-negative BL patients.

The AIDS Malignancy Consortium 048 (AMC 048; Rituximab and Combination Chemotherapy in Treating Patients With Newly Diagnosed, HIV-Associated Burkitt’s Lymphoma) trial, which to the best of our knowledge was the first dedicated phase 2 clinical therapeutic study in HIV-associated BL, sought to determine whether intensive therapy was feasible and appropriate in the HAART era. We prospectively studied a further modification of the CODOX-M/IVAC regimen previously reported in 14 HIV-negative patients,19 after noting that the various BL regimens had not been prospectively compared.

Patients and methods

Eligibility

This research protocol was approved by each site’s institutional review boards and all participants gave written informed consent. Patients with documented HIV infection and newly diagnosed untreated BL or atypical BL per World Health Organization criteria20 were eligible. As of 2009, the new World Health Organization criteria replaced “atypical BL” with “B cell lymphoma unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma.”

Adequate cardiac (ejection fraction ≥50%), renal (serum creatinine of ≤1.5 mg/dL or creatinine clearance ≤60 mL/minute), and hepatic function (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase ≤3 × the upper limit of normal and a direct bilirubin level of ≤2.0 mg/dL) was required unless it was secondary to antiretroviral therapy, in which the total bilirubin cutoff was ≤3.5 mg/dL, provided that the direct bilirubin was normal. An absolute neutrophil count ≥1000/µL and platelets ≥50 000/µL were necessary unless they were disease-related. A Karnofsky performance status >30% was required, given the aggressiveness of this disease and the often severely debilitated nature of the patients at initial presentation. Prior malignancies were excluded unless the patient had been disease free >5 years other than having curatively treated cutaneous basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma, carcinoma in situ of the cervix, or cutaneous Kaposi’s sarcoma. Nonmeasurable disease (eg, isolated bone marrow involvement) was allowed.

Patients could enroll onto the study after a prephase treatment of steroids for up to 7 days alone or in combination with a non-CHOP regimen necessary for patient stabilization (eg, cyclophosphamide for normalization of disease-related hyperbilirubinemia). In addition, patients could be enrolled after 1 cycle of CHOP or fractionated CHOP (eg, CODOX) with or without rituximab. This allowed patients to enroll if they had either newly diagnosed HIV infection after chemotherapy initiation or minimal therapy for disease stabilization elsewhere and were transferred to a tertiary care center.

For evaluation of occult leptomeningeal disease, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was obtained prior to systemic chemotherapy unless thrombocytopenia or leukemic disease precluded safe lumbar puncture. Three cubic centimeters of CSF was evaluated for CD19, CD10, and CD45 by routine flow cytometry methods at each institution. If there were sufficient cells, κ and λ light chain assays were also performed. For subsequent lumbar punctures, only cell count and cytology were required.

Treatment plan

Treatment in AMC 048 (Table 1) was based on the original National Cancer Institute Magrath regimen6 and subsequent modifications made by Lacasce et al.19 The goals of additional changes pursued in AMC 048 and their brief rationales are included in the supplemental Data available at the Blood Web site. Pretreatment evaluations included standard blood work, total body computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging scan, bone marrow biopsy, and CSF analysis, including routine studies, cytology, and flow cytometry. Positron emission tomography scan was recommended but not required.

Table 1.

AMC 048 treatment plan

| Treatment | Day | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14-28 | |

| Regimen A: R-CODOX-M* | ||||||||||||||

| Rituximab 375 mg/m2 IVPB | X† | |||||||||||||

| Cyclophosphamide 800 mg/m2 IVPB | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 IVP‡ | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 IVP | X | |||||||||||||

| Pegfilgrastim 6 mg§ | X | |||||||||||||

| Methotrexate 3000 mg/m2 IVPB|| | X (day 15) | |||||||||||||

| Leucovorin IVPB | X¶ | |||||||||||||

| Cytarabine 50 mg IT | X# | X** | ||||||||||||

| Methotrexate 12 mg IT | X# | |||||||||||||

| G-CSF†† | X†† (approximately day 18) | |||||||||||||

| Regimen B: IVAC* | ||||||||||||||

| Rituximab 375 mg/m2 IVPB | X | |||||||||||||

| Ifosfamide 1500 mg/m2 IVCI | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Mensa 1500 mg/m2 IVCI | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Etoposide 60 mg/m2 IVCI | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Cytarabine 2000 mg/m2 IVPB (no cap) every 12 h × 4 doses | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Methotrexate 12 mg IT | X | |||||||||||||

| Pegfilgrastim 6 mg§ | X | |||||||||||||

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IVCI, intravenous continuous infusion; IVP, intravenous push; IVPB, intravenous piggyback.

Patients with low-risk disease received 3 cycles of regimen A. Patients with high-risk disease received 4 alternating cycles of regimens A and B.

Rituximab was given once each cycle. Acute presentation of high-grade lymphoma and scheduling constraints may make it difficult to administer rituximab on the first day of each cycle. Rituximab was given up to 3 days before a chemotherapy cycle and any time within the cycle such that a total of 4 doses were given with this regimen for patients with high-risk disease. A missed dose was made up within 28 days of the last dose of IVAC.

Vincristine maximum 2-mg dose. Delays by a few days were allowed to accommodate scheduling or treatment of constipation.

Methotrexate levels were drawn 24, 48, and 72 hours after treatment, with anticipated decrement in levels of 10-fold every 24 hours.

Leucovorin was administered 24 hours after methotrexate and was initiated with a dose of 200 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) followed by 25 mg/m2 IV every 6 hours until the methotrexate level reached <50 nmol/L. Leucovorin was titrated for delayed methotrexate clearance or increases in creatinine.

Methotrexate (12 mg intrathecally [IT]) mixed with cytarabine (50 mg IT) given on day 1. Hydrocortisone 50 mg was given to reduce arachnoiditis.

G-CSF: Restarted after methotrexate levels had dropped below 50 nmol/L and continued until absolute neutrophil count (ANC) reached >1000 cells per μL.

If pegfilgrastim was not available, G-CSF was given once per day until ANC >1000 cells per μL was substituted.

Patients with high-risk disease received additional IT cytarabine 50 mg on day 3.

The protocol required baseline CSF flow cytometry, but it was completed in only 15 patients. The flow cytometry was performed at the individual site referencing an appendix that specified immediate processing and cell count–dependent antibody staining. Specifically, a cell count of zero engendered a 3-color flow of CD19 κ and λ in a single tube. A cell count of one required 2 tubes for evaluation separating out the κ and λ while duplicating the other antibodies. Additional evaluations were at the discretion of the laboratory.

Treatment administration

Per the original CODOX-M/IVAC regimen, we defined low-risk disease as stage I, with a single focus of disease <10 cm and normal lactate dehydrogenase or intra-abdominal disease only and total resection and normal lactate dehydrogenase after surgery. Patients with low-risk disease received 3 cycles of rituximab and CODOX-M (R-CODOX-M). All other patients were considered high risk and received R-CODOX-M/IVAC in an R-CODOX-M/IVAC/R-CODOX-M/IVAC sequence for a total of 4 cycles. Because anasarca, pleural effusions, or ascites can cause methotrexate pooling and delayed clearance, treatment could be given in a reverse sequence: IVAC/R-CODOX-M/IVAC. R-CODOX-M cycles were to remain 21 to 28 days long.

Patients with CNS disease were to be treated with an intensified prophylaxis regimen. If the patient had CNS disease, treatment of the leptomeninges with liposomal cytarabine and methotrexate was matched to the appropriate cycle. Specifically, liposomal cytarabine was administered on day 1 or 3 of the CODOX-M cycle and was not administered in any of the IVAC cycles. IT methotrexate was administered in the IVAC cycles. Details are provided in supplemental Data. Of note, no patients with parenchymal CNS disease at diagnosis were enrolled. Details of prophylaxis for Pneumocystis, Mycobacterium avium complex, and neutropenic fever are outlined in supplemental Data.

Correlative studies

Immunohistochemistry studies were performed by using standard techniques for p53, interferon regulatory factor 4/multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (IRF4/MUM1), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) –encoded small RNAs (EBERs) in situ hybridization.

Statistics

The primary end point was 1-year overall survival (OS) because treatment failures tend to be either immediate or within the first few months after treatment completion. Relapse after 1 year of follow-up after treatment of BL is exceedingly rare.

A sample size of 31 patients was needed to test the null hypothesis that the 1-year OS rate was 0.65 against the alternative that it was 0.85 at the 1-sided 0.10 significance level with power of 0.90 using a nonparametric survival model.21 To allow for a 10% dropout rate, 34 patients were enrolled. An early stopping rule was to be invoked for treatment-related mortality, including infection-related death, and was derived by determining the number of infection-related deaths. This would occur <10% of the time if the true infection-related mortality rate was <4%. This stopping rule was designed to detect a twofold or greater increased risk of treatment-related death compared with AMC 010.22 The stopping rule had a power of 0.90. The remainder of the statistical methods can be found in supplemental Data.

Results

Patient characteristics

From 2007 to 2010, 13 AMCs enrolled 34 patients (Table 2), all but 2 of whom were high risk. Four had evidence of leptomeningeal disease, none had parenchymal CNS disease, 88% were male, 65% were white, 15% were African American, and 24% were Hispanic. The median age was 42 years (range, 19-55 years). Only 9% were IV drug users. Median HIV viral load was 1819 copies per μL with only 12 patients having a viral load <100 copies per μL and only 1 patient having <20 copies per μL. Most patients (26 of 31) were given HAART at study entry, and 3 patients were receiving their second or greater HAART regimens. The median CD4 count was 195 cells per μL (range, 0-721 cells per μL). CD4 was less than 100 cells per μL in 5 patients (15%). HIV replication was measured at initiation, at completion of chemotherapy, and every 4 months for 2 years. Of 10 patients with undetectable HIV viral load at baseline, 2 had detectable HIV viral loads during the study. Of 8 patients who were not receiving antiretroviral therapy at baseline, 2 began receiving antiretroviral therapy during the study.

Table 2.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 | 88 |

| Female | 4 | 12 |

| Race | ||

| White | 22 | 65 |

| African American | 5 | 15 |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 3 |

| Asian | 2 | 6 |

| Unknown | 4 | 12 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 8 | 24 |

| Non-Hispanic | 26 | 76 |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 42.0 | |

| Range | 19-55 | |

| CDC risk group | ||

| Homosexual/bisexual contact | 14 | 41 |

| Heterosexual contact | 10 | 29 |

| IVDU | 3 | 9 |

| Heterosexual contact and IVDU | 1 | 3 |

| Homosexual/bisexual and heterosexual contact | 3 | 9 |

| Other (needle sticks, congenital HIV, unknown) | 3 | 9 |

| Receiving HAART at diagnosis | 26 | 76 |

| Absolute CD4 count (n = 33) | ||

| Median | 195.0 | |

| SD | 174.6 | |

| Min-max | 0-721 | |

| HIV load (n = 33) | ||

| Median | 1819 | |

| Min-max | Undetectable-1 187 968 | |

| Ann Arbor stage | ||

| I | 4 | 12 |

| II | 2 | 6 |

| IIE | 1 | 3 |

| III | 2 | 6 |

| IV | 25 | 74 |

| Karnofsky performance status | ||

| 40%-60% | 7 | 23 |

| >70% | 26 | 77 |

| Local pathology diagnosis (n = 35) | ||

| BL | 33 | 97 |

| Burkitt-like lymphoma | 1 | 3 |

| Central pathology diagnosis (n = 25) | ||

| BL | 17 | 71 |

| High-grade, unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma with features intermediate between DLBCL and atypical BL | 3 | 21 |

| Indeterminate between DLBCL and BL | 1 | 7 |

| DLBCL | 3 | 6 |

| High-grade NHL, not otherwise specified | 1 | 7 |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IVDU, intravenous drug user; SD, standard deviation.

Central pathology review

Pathology reported by the referring institution was BL in all but 1 patient who had atypical BL. Central pathology review was performed for 25 of 34 patients. Other patients did not have available immunohistochemistry slides or tissue blocks. The diagnosis was BL (19), high-grade lymphoma with features intermediate between BL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (2), DLBCL (3), and high-grade NHL, not otherwise specified (1). All evaluable patients were CD20+CD10+ and had a Ki-67 of 90% (4) or >95% (21). Fluorescence in situ hybridization for MYC using a break-apart probe was performed for patients in whom the immunophenotype and morphology were not obvious for a diagnosis of BL. Two of the patients with questionable immunophenotype and morphology had myc rearrangements and high proliferation rate, but both had large cells, which are morphologically consistent with DLBCL, not BL. One of these patients was BCL2-positive and BCL6-negative, which ruled out BL, and the second patient was BCL6-postive and was considered to have MYC-positive germinal center-DLBCL. A third patient was classified as having DLBCL because of clear morphologic features, but no material was available for fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis. Because of interobserver variability, all patients were included in the analysis.

Treatment outcomes

Details of toxicities are provided in Table 3. Grade 3 to 4 toxicity occurred at least once in 27 patients. In 20 patients, toxicity was hematologic: 17 patients had anemia, 16 had neutropenia despite prophylactic hematopoietic growth factors, and 21 had thrombocytopenia. Grade 4 transfusion level anemia occurred in 6 patients (18%) and thrombocytopenia occurred in 20 (59%); 26 patients had nonhematologic grade 3 to 4 toxicities, with electrolyte and neurologic disturbances being the most common. Neutropenic fever occurred in 8 (24%) of 34 patients.

Table 3.

AEs at the patient level (most severe grade)

| AE | Grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/2 | 3/4 | 5 | |

| Total | 27 | 4 | |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 21 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 16 | 0 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Allergic reaction | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary/thoracic | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Cardiac | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Opthalmologic | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| GI | 10 | 6 | 1 |

| Pain | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | 3 | 13 | 1 |

| Metabolic (excluding tumor lysis) | 6 | 34 | 0 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Neurologic | 6 | 7 | 1 |

| Myelodysplasia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Renal | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Psychiatric | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Dermatologic | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Nonmalignancy complications of HIV | N/A | N/A | 1 |

N/A, not applicable.

Table 4 outlines treatment completion status; 68% of patients completed the treatment. Early termination of therapy was a result of disease progression in 9%, adverse events in 12%, and patient withdrawal in 3%. Adverse events leading to early termination were hematologic (3), neurologic (2), or hepatic/infectious (1).

Table 4.

Treatment status

| Status | Low risk (n = 2) | High risk (n = 32) | Total (n = 34) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Treatment completed per protocol | 2 | 100 | 21 | 66 | 23 | 68 |

| Disease progression | 0 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 9 | |

| Early termination | ||||||

| Adverse event | 0 | 5 | 16 | 5 | 15 | |

| Patient withdrawal | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Counts did not recover within time frame to begin cycle 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Other complicating disease | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | ||

Patient #6 terminated treatment because of low platelet count (grade 4) and infection (grade 3) possibly related to doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Patient #3 terminated treatment because of left hemiparesis (grade 3), possibly related to cytarabine and vincristine. Patient #1 terminated treatment because of confusion (grade 3) unrelated to treatment. Patient #27 terminated treatment because of grade 3 encephalopathy and grade 3 pneumonitis/pulmonary infiltrates. The encephalopathy was reported as possibly related to treatment. (This patient with pretreatment cirrhosis died 35 days later because of hepatic failure with contributing causes listed as hepatitis B, cirrhosis, pneumonia, and HIV, and death as a result of treatment toxicity was reported.) Patient #30 terminated treatment because of grade 4 neutropenia and grade 3 white blood cell count, which were probably/possibly related to treatment.

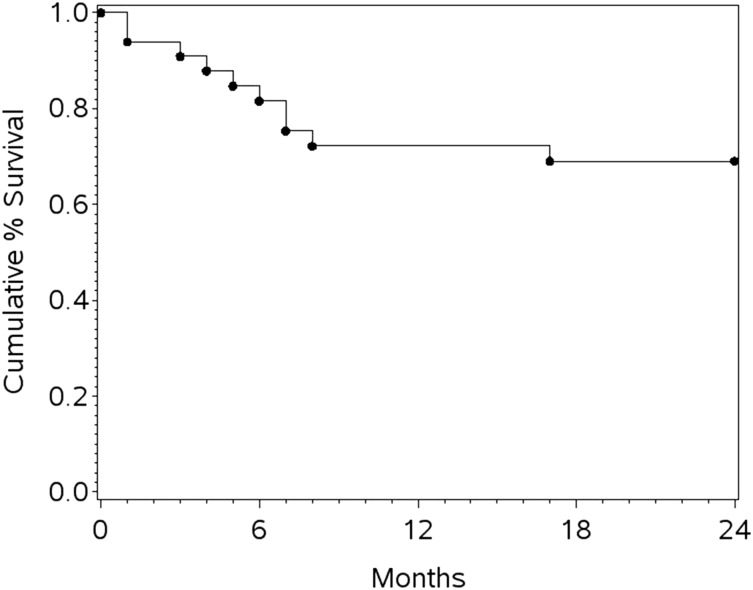

The last patient completed treatment in 2011, and the protocol required 2-year follow-up after the last treatment in 2013. The analysis was completed in 2014. The median follow-up was 26 months. Despite early terminations, the 1-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 69% (95% CI, 51%-82%), the 1-year OS (the primary end point) was 72% (95% CI, 53%-85%), and 2-year OS was 69% (95% CI, 50%-82%) (Figure 1). When restricted to 19 patients with confirmed BL by central pathology review, the 1-year PFS was 72.2% (95% CI, 45.6%-87.4%) and OS was 78% (95% CI, 51%-91.0%). Not surprisingly, the 1-year OS was superior for those who completed all 4 cycles of treatment (86% [95% CI, 62%-95%]) compared with those who did not (48% [95% CI, 18%-73%]; P < .001, log-rank test). Of note, little drop-off was seen after the first year, with only 1 patient progressing between years 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Cumulative survival for all enrolled patients.

Overall, 11 patients died. One patient died of treatment-related toxicity characterized by encephalopathy, with hepatic failure, hepatitis B, and pneumonia being contributing causes. This patient entered the study with cirrhosis but met eligibility criteria. Eight died of systemic disease progression, including 1 patient who died as a result of CNS disease who did not have CNS disease at baseline. During the follow-up period, 1 patient died in remission of fungal infection and 1 died of nonmalignant complications of HIV.

At study entry, 26 of 31 patients were receiving HAART. The complete response and 1-year OS did not show a statistically significant difference based on receipt of HAART at study entry, possibly because of small numbers of patients, as it was higher for those receiving HAART (86% vs 50%), possibly because of small numbers of patients. Similarly, low baseline CD4 (<100) or high baseline CD4 (≥100) did not predict a different outcome with respect to these measures.

Correlative studies

The immunohistochemistry panel was performed as feasible, depending on the availability of material. Non-BL–defining proteins did not correlate with OS: EBER positive (8 of 16) or negative and p53 positive (10 of 10) or negative. Notably, however, staining for p53 fell into 3 groups: 9 had <10%, 3 had 30% to 60%, and 8 had 80% to more than 95%. IRF4/MUM1 staining was not significantly associated with OS. There were 6 MUM1-positive patients, 2 of whom died and 14 MUM1-negative patients, 3 of whom died. The hazard ratio for MUM1-positive vs MUM1-negative for OS was 1.42 (95% CI, 0.24-8.53; P = .70). Within the subset of patients with confirmed BL, MUM1-positivity also did not predict survival (hazard ratio, 1.70; 95% CI, 0.24-12.05). None of the patient tissues stained for the multidrug-resistant protein.

Occult leptomeningeal disease

We sought to investigate the use of flow cytometry to identify cytologically occult leptomeningeal disease at baseline in BL and determine its prognostic significance. CSF by cell count and cytology in 15 evaluable patients was negative in 12, positive in 2, and atypical in 1. Flow cytometry did not identify disease in the 12 cytology-negative patients. Flow cytometry was positive in 3 patients: one with atypical cytology, one with positive cytology, and one with unavailable cytology.

EBV in tumor

EBV-driven lymphomas may develop via a unique pathway that may be more resistant to chemotherapy. Alternatively, nuclear factor kappa B activation in these tumors may create a new therapeutic target. As noted above, EBER staining (positive or negative) was variable in our sample (8 of 16) but did not predict for OS.

Discussion

AMC 048 modified the CODOX-M/IVAC regimen to reduce toxicity while maintaining or improving the survival rate of patients with HIV-associated BL. The study was initiated at a time when treating HIV-related lymphoma intensively was controversial because of excess chemotherapy-related toxicity in the pre-HAART era. Retrospective studies, including one of CODOX-M/IVAC in the HAART era,18 suggested that high-risk patients with HIV-related BL could do well with intensive chemotherapy. In AMC 048, the 1-year OS was 72% (95% CI, 53%-85%), reasonably within reach of our 85% goal. We also reduced morbidity, which compared favorably to the nearly universal toxicity of the unmodified parent regimen. Of particular note, we eliminated grade 3 and 4 mucositis. Nonhematologic toxicities were also manageable except in 1 patient with pretreatment cirrhosis who died of liver failure.

In this study, despite early terminations, 1-year PFS was 69% (95% CI, 51%-82%), 1-year OS (the primary end point) was 72% (95% CI, 53%-85%), and 2-year OS was 69% (95% CI, 50%-82%). A study of 30 patients with HIV-associated BL treated with CODOX-M/IVAC resulted in a 3-year OS of 52% and EFS of 75%.23 Similarly, an international study of CODOX-M/IVAC in BL patients not infected with HIV reported a 2-year EFS of 65% and 2-year overall cure rate of 72.8%.7 Nonetheless, our results were inferior to the previous Magrath report of 92% 2-year EFS,6,7 which included 39 adults and 33 children and no patients with HIV infection.

Although we cannot say which individual modification contributed to the success of the program, rituximab may have had a positive impact. One study in HIV-negative patients treated with a hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone/cytarabine/methotrexate regimen strongly suggested that rituximab improved relapse-free survival and OS compared with a historical cohort.24 In another retrospective study of 80 BL patients who received CODOX-M/IVAC, 50% were treated with rituximab. Rituximab was associated with a trend in improvement of 3-year OS of 77% vs 66%, and HIV-positive patients did as well as HIV-negative patients. Regardless, it seems likely that with current supportive care, rituximab does not contribute adversely to toxicity in our modified CODOX-M/IVAC regimen, which was of concern in the AMC 010 study of CHOP with or without rituximab in HIV-related NHL, particularly in the subpopulation of patients with CD4 <50 cells/uL.25

Additionally, limiting the dose of high-dose methotrexate, as previously done by Lacasce,19 and moving it to day 15 outside the CODOX day 10 nadir likely lowered both the incidence of severe mucositis and the rate of neutropenic fever. The incidence of hematologic toxicity, which occurred in 24% of patients, was lower than the nearly 100% toxicity in the unmodified parent regimen. Although we hypothesized that the improved tolerability led to on-time drug administration and overall improved outcomes, this would need to be confirmed in a randomized trial. Similar to the procedures in Lacase,19 we capped vincristine at 2 mg and had no grade 3 to 4 peripheral neuropathy. Although it was unusual, we cannot exclude that vincristine may have played a role in the patient who experienced hemiparesis (a central neurotoxicity). Similarly, we do not attribute toxicity to vincristine in the case of hepatic encephalopathy, which occurred in the patient who died of exacerbation of preexisting cirrhosis (by eligible baseline liver function tests) 35 days after therapy initiation.

Recently, Dunleavy et al26 reported a phase 2 trial in BL using short-course infusional etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and hydroxydaunorubicin plus rituximab (SC-EPOCH-R) for 3 cycles in 11 HIV-positive patients and full-course dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in an additional 19 non-HIV patients. Their 95% EFS and 100% OS exceed our study results. However, the small sample size leads to overlapping 95% CIs for both EFS (72% to 100%) and OS (60% to 98%) with our AMC 048 study. Moreover, none of the 11 HIV-positive patients treated with SC-EPOCH with dose-dense rituximab (SC-EPOCH-RR) had CNS disease, whereas 4 of our patients entered the study with leptomeningeal disease. We suspect the EPOCH backbone is ill suited to treatment of CNS disease because none of the agents included in EPOCH have significant CNS penetration. We postulate that this would be particularly problematic in the setting of baseline CNS parenchymal disease. Although such patients were eligible for our study, none had this baseline characteristic. It is also possible that the CODOX-M/IVAC backbone is more effective for those at high risk of CNS metastases or leptomeningeal disease at presentation.

With regard to toxicity, 88% of the SC-EPOCH-RR/EPOCH-R cycles were administered to outpatients, whereas the AMC 048 regimen required hospitalization for both the high-dose methotrexate and IVAC. Neutropenic fever was similar in the two studies: it occurred in 22% of patients vs 24% of patients in AMC 048. A phase 3 comparison trial between the AMC 048 and the SC-EPOCH-RR regimen would be difficult to conduct because of the rarity of this disease. A large ongoing national confirmatory phase 2 trial (CTSU 9177/AMC 086) of an outpatient regimen of EPOCH-R in BL is currently enrolling patients and includes those with HIV.

In our study, we prospectively analyzed the incidence of cytology-negative but flow cytometry–positive occult leptomeningeal disease. By using the flow cytometric techniques available at the time, which were specified by protocol, none of the 12 cytology specimens studied were flow cytometry positive. In contrast, Hegde et al27 using similar techniques reported that 11 (22%) of 51 patients had positive multicolor flow cytometry in the absence of positive cytology. Their study population had 91% untreated DLBCL with only 9% BL. HIV infection was documented in 54% of those patients. Despite aggressive schedules of direct installation of CSF chemotherapy, including 7 via lumbar puncture and 3 via Ommaya reservoir, 5 patients (45%) had CNS relapse and died. In contrast, in patients at increased risk of CNS involvement but with negative flow cytometry results, the relapse risk was only 8% (3 of 40). In AMC 048, our CNS relapse rate was very low (n = 1) and occurred in a patient with CNS baseline involvement. This may reflect the use of systemic high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine in our regimen, which was not part of the EPOCH study. Given our low rate of CNS relapse, it is not clear that the currently available multiparameter flow with higher sensitivity would yield a different result.

Given that only 19 (76%) of 25 patients had BL after central pathology review, a sensitivity analysis demonstrated that outcomes for confirmed BL did not differ from those with other histologies. Moreover, although dose intensification rather than CHOP-based therapy is important for BL, its benefit for other histologies, such as DLBCL with c-MYC rearrangement, or B-cell lymphoma (unclassifiable) with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL, is less clear. Preliminary data from an ongoing prospective study suggests that EPOCH-R is efficacious for DLBCL with MYC or both MYC and BCL-2 translocation.28 Nonetheless, it is possible that these 5 patients may have been overtreated on AMC 048.

Because we were interested in identifying mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance, we studied p53 mutations and the chemotherapy efflux pump referred to as the multidrug resistance protein. Although p53 staining was nearly dichotomized in our study, it was not predictive of outcome, perhaps because of the small study size. None of the samples stained for multidrug resistance. In our study, protein expression of MUM1/IRF4A, a gene of plasma cell differentiation, also failed to confer a worse prognosis. Further investigations of these markers of potential drug resistance in larger studies are warranted.

Finally, with respect to HAART, its use was at the discretion of the individual investigator. At study entry, 26 of 31 patients were receiving HAART. The protocol specified that physicians could continue or discontinue therapy at the initiation of chemotherapy. In addition, HAART could be discontinued as needed for toxicity. Of note, HAART regimens were exclusive of zidovudine, given its myelosuppression. HIV replication was measured at initiation and completion of chemotherapy and every 4 months for 2 years. Of 10 patients with undetectable HIV viral load at baseline, 2 were found to have detectable HIV viral loads during the study. Of 8 patients who were not receiving antiretroviral therapy at baseline, 2 began antiretroviral therapy during the study. We cannot make any definitive conclusions about the role of HAART regarding outcomes.

Concurrent vs discontinued HAART therapy is a controversial area of investigation. Fearing drug interactions, the National Cancer Institute investigators discontinued HAART therapy during EPOCH for HIV-associated NHL (largely DLBCL); 5-year PFS and OS were 79% and 80%, respectively.29 With HAART reinitiation, HIV suppression and baseline CD4 were regained within 6 months. Because HIV viral suppression and immune reconstitution correlate with sustained disease-free survival,30 HAART reinitiation is highly desirable and all patients completing BL treatment receive HAART even if it is interrupted during chemotherapy.

In summary, in AMC 048, we were able to aggressively treat HIV-infected patients with BL and achieve high rates of long-term disease remission with a modified intensive CODOX-M/IVAC plus rituximab (CODOX-M/IVAC-R) regimen that minimized drug-related toxicity. Although CTSU 9177/AMC 086 is investigating an outpatient regimen of EPOCH-R in BL, the modified AMC 048 version of CODOX-M/IVAC-R may better serve patients who present with CNS disease or are at high risk for CNS relapse (eg, patients with bone marrow, testicular, or multiple extranodal sites), because it contains high-dose cytarabine and methotrexate, drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier. Consequently, AMC 048 represents a reasonable treatment option in the appropriate setting, possibly irrespective of HIV status.

Acknowledgments

This trial was supported by Grant No. U01CA121947 from the National Cancer Institute for the AIDS Malignancy Consortium.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.N., J.Y.L., E.C., R.A., and L.K. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and R.B., E.R., L.R., and N.W.-J. performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of members of the AIDS Malignancy Consortium can be found in the supplemental Data.

Correspondence: Ariela Noy, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: noya@mskcc.org.

References

- 1.Burkitt D. Long-term remissions following one and two-dose chemotherapy for African lymphoma. Cancer. 1967;20(5):756–759. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1967)20:5<756::aid-cncr2820200530>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostronoff M, Soussain C, Zambon E, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma in adults: a retrospective study of 46 cases. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1992;34(5):389–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straus DJ. Treatment of Burkitt’s lymphoma in HIV-positive patients. Biomed Pharmacother. 1996;50(9):447–450. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(97)86004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straus DJ, Huang J, Testa MA, Levine AM, Kaplan LD National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Prognostic factors in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: analysis of AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol 142—low-dose versus standard-dose m-BACOD plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(11):3601–3606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan LD, Straus DJ, Testa MA, et al. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Low-dose compared with standard-dose m-BACOD chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(23):1641–1648. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706053362304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magrath I, Adde M, Shad A, et al. Adults and children with small non-cleaved-cell lymphoma have a similar excellent outcome when treated with the same chemotherapy regimen. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):925–934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mead GM, Sydes MR, Walewski J, et al. UKLG LY06 collaborators. An international evaluation of CODOX-M and CODOX-M alternating with IVAC in adult Burkitt’s lymphoma: results of United Kingdom Lymphoma Group LY06 study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(8):1264–1274. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas DA, Cortes J, O’Brien S, et al. Hyper-CVAD program in Burkitt’s-type adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2461–2470. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patte C, Michon J, Frappaz D, et al. Therapy of Burkitt and other B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and lymphoma: experience with the LMB protocols of the SFOP (French Paediatric Oncology Society) in children and adults. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1994;7(2):339–348. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(05)80206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Gaidano G, et al. AIDS-related Burkitt’s lymphoma. Morphologic and immunophenotypic study of biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103(5):561–567. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.5.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine AM. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma. Blood. 1992;80(1):8–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beral V, Peterman T, Berkelman R, Jaffe H. AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;337(8745):805–809. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson TM, Morton LM, Shiels MS, Clarke CA, Engels EA. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes in HIV-infected people during the HAART era: a population-based study. AIDS. 2014;28(15):2313–2318. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spina M, Tirelli U, Zagonel V, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma in adults with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection: a single-institution clinicopathologic study of 75 patients. Cancer. 1998;82(4):766–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davi F, Delecluse HJ, Guiet P, et al. Burkitt’s Lymphoma Study Group. Burkitt-like lymphomas in AIDS patients: characterization within a series of 103 human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(12):3788–3795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill PS, Levine AM, Krailo M, et al. AIDS-related malignant lymphoma: results of prospective treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(9):1322–1328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.9.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim ST, Karim R, Tulpule A, Nathwani BN, Levine AM. Prognostic factors in HIV-related diffuse large-cell lymphoma: before versus after highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8477–8482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ES, Straus DJ, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. Intensive chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC) for human immunodeficiency virus-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1196–1205. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacasce A, Howard O, Lib S, et al. Modified magrath regimens for adults with Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphomas: preserved efficacy with decreased toxicity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(4):761–767. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000141301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conover W. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. Practical Nonparametric Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan LD, Lee JY, Ambinder RF, et al. Rituximab does not improve clinical outcome in a randomized phase 3 trial of CHOP with or without rituximab in patients with HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma: AIDS-Malignancies Consortium Trial 010. Blood. 2005;106(5):1538–1543. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montoto S, Wilson J, Shaw K, et al. Excellent immunological recovery following CODOX-M/IVAC, an effective intensive chemotherapy for HIV-associated Burkitt’s lymphoma. AIDS. 2010;24(6):851–856. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283301578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas DA, Faderl S, O’Brien S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with hyper-CVAD plus rituximab for the treatment of adult Burkitt and Burkitt-type lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;106(7):1569–1580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan LD, Lee J, Ambinder RF. Rituximab does not improve clinical outcome in a randomized phase 3 trial of CHOP with or without rituximab in patients with HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma: AIDS-Malignancies Consortium Trial 010. Blood. 2005;106(5):1538-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunleavy K, Little RF, Pittaluga S, et al. The role of tumor histogenesis, FDG-PET, and short-course EPOCH with dose-dense rituximab (SC-EPOCH-RR) in HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115(15):3017–3024. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegde U, Filie A, Little RF, et al. High incidence of occult leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry in newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas at risk for central nervous system involvement: the role of flow cytometry versus cytology. Blood. 2005;105(2):496–502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunleavy KF, Fanale M, LaCasce A, et al. Preliminary Report of a Multicenter Prospective Phase II Study of DA-EPOCH-R in MYC-Rearranged Aggressive B-Cell Lymphoma [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 395. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little RF, Pittaluga S, Grant N, et al. Highly effective treatment of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma with dose-adjusted EPOCH: impact of antiretroviral therapy suspension and tumor biology. Blood. 2003;101(12):4653–4659. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antinori A, Cingolani A, Alba L, et al. Better response to chemotherapy and prolonged survival in AIDS-related lymphomas responding to highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15(12):1483–1491. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108170-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]