Abstract

Opsonin-independent phagocytosis of Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is important in defense against neonatal GBS infections. A recent study indicated a role for GBS pilus in macrophage phagocytosis. We studied 163 isolates from different phylogenetic backgrounds and those possessing or lacking the gene encoding the pilus backbone protein, Spb1 (SAN1518, PI-2b) and spb1-deficient mutants of wild-type (WT) serotype III-3 GBS 874391 in non-opsonic phagocytosis assays using J774A.1 macrophages. Numbers of GBS phagocytosed differed up to 23-fold depending on phylogenetic background; isolates possessing spb1 were phagocytosed more than isolates lacking spb1. Comparing WT GBS and isogenic spb1-deficient mutants showed WT was phagocytosed better compared to mutants; Spb1 also enhanced intracellular survival as mutants were killed more efficiently. Complementation of mutants restored phagocytosis and resistance to killing in J774A.1 macrophages. Spb1 antiserum revealed surface expression in WT GBS and spatial distribution relative to capsular polysaccharide. spb1 did not affect macrophage nitric oxide and TNF-alpha responses; differences in phagocytosis did not correlate with N-acetyl D-glucosamine (from GBS cell wall) according to enzyme-linked lectin-sorbent assay. Together, these findings support a role for phylogenetic lineage and Spb1 in opsonin-independent phagocytosis and intracellular survival of GBS in J774A.1 macrophages.

Keywords: GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS, STREPTOCOCCUS AGALACTIAE, MACROPHAGE, PHAGOCYTOSIS, PILUS, INTRACELLULAR SURVIVAL

1. INTRODUCTION

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is an important cause of infection in newborns, pregnant women and older persons with chronic medical illness [1]. Early onset neonatal infection results from exposure of infants to bacteria that colonize (usually asymptomatically) the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tracts of their mothers [2]. Up to 72% of infants born to colonized mothers also become colonized by ascending spread of GBS after rupture of membranes or direct contact with infected amniotic fluid or urogenital secretions [2, 3]. GBS also causes pneumonia, bacteraemia, and skin and soft tissue infections including urinary tract infections [4, 5].

Immune clearance of GBS is mediated in part by anti-capsular antibody. A deficiency of serum anti-type III capsular polysaccharide antibody increases the risk of infection with serotype III GBS [6]. In neonates, anti-capsular IgG is acquired transplacentally from mothers; however, GBS capsular polysaccharide is poorly immunogenic, even after multiple exposures, and only 10-20% of women have levels of type-specific antibody high enough to be able to confer protection to their infants [7]. Neonates also have lower serum concentrations of complement factors than do adults [8]. Thus, opsonin-independent defenses are important in resistance to GBS [9, 10]. In addition, serotype III GBS can survive inside macrophages for extended periods following non-opsonic phagocytosis [11-13] and induce macrophage apoptosis [14, 15], which may contribute to defective inflammatory responses during neonatal GBS infection [16].

GBS are divided into ten serotypes, based on the composition of the capsular polysaccharide. Types I, II, III, and V are the major serotypes that cause infection in neonates [17]. The population structure of GBS is clonal and phylogenetic lineages can be identified by analysis of multi-locus enzyme electrophoresis, restriction-digestion patterns (RDP) of chromosomal DNA, or multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [18-20]. RDP analysis provides whole-genome comparisons that are highly discriminatory and useful for epidemiological studies whereas MLST, based on 500 bp nucleotide sequences of seven housekeeping genes is important for studying genetic lineage and population structure of GBS [18, 21, 22]. In the case of type III GBS, this classification has been associated with differences in virulence. RDP subtype III-3 (equivalent to MLST type ST-17) GBS, for example, are responsible for a disproportionate number of neonatal infections [18-20, 23]. In a search for virulence factors unique to RDP III-3 GBS subtractive hybridization experiments identified DNA sequences present only in RDP III-3 isolates, but not in less invasive phylogenetic subgroups [24]. This led to the identification of the gene encoding the GBS invasin, surface protein of GBS 1 (spb1), which encodes a protein that promotes invasion of epithelial cells [25]. Recently, spb1 was shown to be part of the pilus locus and Spb1 has been identified as Pilus Island (PI)-2b; the pilus backbone protein in GBS strains 874391 (serotype III), COH1 (III) and A909 (Ia) [26-28]. A more recent study by Maisey et al (2008) showed that another variant of the pilus backbone protein, PilB, present in GBS NCTC10/84 (V) promotes phagocyte resistance and systemic virulence [29].

In this study, we investigated whether phylogenetic lineage (i.e. serotype and RDP subtype) and spb1 affects the ability of J774A.1 macrophages to phagocytose and kill GBS in the absence of opsonin. The results show that the efficiency at which phagocytosis and intracellular survival of GBS occurs in macrophages is dependent on phylogenetic lineage, and this is, in part, related to the presence of Spb1.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Bacteria

The majority of isolates of each serotype and subtype of GBS used are described elsewhere [20] (Table 1). Additional isolates of each subtype were also used to total 163 isolates. An isogenic mutant of III-3 GBS 874391 expressing a markedly truncated copy of spb1 (Spb1-/tr) and a Spb1-/tr strain complemented in trans by a full-length plasmid-encoded copy of spb1 (strain Spb1trC) were also used [25]. An in-frame deletion mutant of the complete spb1 gene in GBS 874391 (Spb1-/-) was generated at Institut Pasteur according to methods described elsewhere [28, 30] and provided for this study. This complete in-frame deletion mutant and its complemented strain (Spb1C) were used to compare results generated with the truncated Spb1-/tr mutant. GBS were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth and agar with 5 μg/ml erythromycin as indicated.

Table 1.

RDP subtype, total number of isolates tested (N) and number possessing (positive) spb1 by Southern blot.

| RDP | N | Positive for spb1 | Representative GBS Isolate(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ia-1 | 7 | 7 | 842088, 874279, 873325, 843963, 882201 |

| Ia-2 | 14 | 0 | 871922, 853817, 873843, 841557 |

| Ia-3, 4 | 7 | 7 | 510012, 560249, 841254, 853402, 630653 |

| Ib-1 | 14 | 1 | 570322 |

| II-1 | 2 | 0 | 854029 |

| II-2 | 5 | 0 | Washington |

| II-3 | 2 | 0 | Evans |

| III-1 | 3 | 0 | 880557 |

| III-2 | 18 | 0 | C44, 871952, 843118, 872809, 530119 |

| III-3 | 41 | 41 | 874391, 610577, 620543, I43, I27, I30 |

| III-4 | 3 | 3 | 870071 |

| V-1 | 2 | 0 | 861815 |

| V-2 | 5 | 0 | 883014 |

| V-3 | 21 | 2 | 900225 |

| VI-1 | 9 | 0 | 861963 |

| VIII-1 | 10 | 10 | 880373 |

2.2 Southern Blot Hybridization

A spb1 probe was prepared by amplifying the 5’ coding region by PCR (spb1 sense 5’ GATAGCTTTTGCCCTCGAGACAGGG 3’, antisense 5’ CAGTGCTAGAAACATAATAGAATTCATATTG GGAAAC 3’). The amplification product was cloned into a pCR2.1 phagemid vector (Invitrogen). The probes were excised by digestion with EcoR I and purified from agarose gel (QIAEX II gel purification kit, Qiagen Inc., Valencia CA). Genomic DNA was prepared from GBS as previously described [25]. For dot blots, DNA was applied to nylon membranes, and hybridized with P32dCTP-labelled spb1 probe (Nick Translation Kit, Amersham).

2.3 Macrophage Culture

J774A.1 murine macrophages (No. TIB-67, ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown as previously described [14]. Human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs) were obtained by treating U937 cells (No. CRL-1593.2 ATCC) with 50 ng ml−1 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate as described elsewhere [15]. For NO assays, 15 mM BH4 (a cofactor for NO synthesis) was added prior to infection [31-34].

2.4 Phagocytosis and Intracellular Survival Assays

Monolayers of macrophages were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 bacteria per macrophage for 2 h. GBS were quantified by OD600nm (Spectronic Genesys 20, Milton Roy, USA) and colony counts on agar. After infection monolayers were washed with PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria and fresh tissue culture media (TCM) with (or without) 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 100 μg ml−1 gentamicin were added. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 (30 min as t=0, or 24 h). Monolayers (n=3) were rinsed with PBS, and macrophages were lysed with 0.01% Triton X100 in distilled water. GBS were quantified by colony counts [12]. Exclusion of antibiotics allowed analysis of total cell-associated (bound, internalized) and intracellular surviving GBS.

2.5 Expression of Spb1 and Generation of Antisera

The sequence for Spb1 was amplified from GBS 874391 DNA using 5’ GGCGGCCTCGAGGCTGAGACAGGGACAATTAC 3’ and 5’ GGCGGCGGATCCTCACTCAGTACCTTTGTTATTTTC 3’ (restriction sites for XhoI and BamHI underlined) primers. The amplicon did not include the sequence for the C-terminal ’LPSTG’ motif and the remaining C-terminus. The amplicon was subcloned into the E. coli vector pET15b (Novagen Inc.) and the recombinant plasmid (pESpb1) was transformed into E. coli Rosetta (DE3) plysS (Novagen Inc.). The DNA sequence was verified by sequencing of the pESpb1 plasmid. For expression, bacteria were grown in LB both containing 0.2% glucose, 50 mg/ml ampicillin and 30 mg/ml chloramphenicol at 37°C. Isopropyl thio-β-D-galactoside was added (0.4 mM) for induction. For purification, frozen E. coli were lysed in 20 mM HEPES, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 mM benzamidine hydrochloride pH 7.3 by repeated freezing and thawing. The suspension was treated with DNAse I and cell free extract collected by centrifugation at 18,000 rpm for 1 hr. Recombinant Spb1 was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography on TALON (Clonetech Inc.) columns using imidazole (5–300 mM). Fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris HCl buffer pH 8.0. Purified protein was used to immunize rats for raising anti-Spb1 polyclonal sera.

2.6 Immunoblotting

GBS cell-wall extracts were prepared using mutanolysin (200 U/ml) for digestion at 37°C overnight as described elsewhere [30]. Purified Spb1 from E. coli or GBS cell-wall extracts were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels containing 1% SDS. For some blots, proteins were boiled in formic acid (pH 2.0, 5 min), lyophilized, and resuspended in running buffer in an attempt to increase entry of proteins into the resolving gel [35-37]. Proteins were electro-blotted to nitrocellulose, incubated with 1% BSA in PBST, washed, incubated with anti-Spb1 serum (1:500), washed, and incubated with goat anti-rat IgG-horseradish peroxidase (1:5000, Biorad). After washing, bands were visualized with a 4-chloro-1napthol/H2O2 substrate (Biorad).

2.7 Immunogold and capsular-specific TEM

Localization of Spb1 in GBS 874391 was initially analyzed using TEM essentially as previously described [38, 39]. Briefly, bacteria from 5 ml overnight THB cultures (150 rpm 37°C) were adhered to glow discharged formvar coated copper grids, and after blocking, samples were reacted with anti-Spb1 sera (1:100) and IgG gold conjugate (10 nm diameter, dilution 1:25). Cells were not fixed with paraformaldehyde [40] but were prepared carefully to minimize potential loss of surface-associated Spb1. In subsequent experiments undertaken to investigate the location of Spb1 and distribution in relation to the capsular polysaccharide (destroyed by standard methods above) cells were high pressure frozen in a Leica EMPACT2 freezer and processed using the following protocols. Cells to be used for detailed morphological studies of capsule were cryosubstituted in 1% osmium tetroxide 0.5% uranyl acetate 5% water in acetone, gradually warmed to room temperature and embedded in Epon resin. Cells for immunolabelling studies were cryosubstituted in 0.2% uranyl acetate 5% water in acetone, warmed to −50oC and embedded in Lowicryl HM20 resin which was polymerised under UV light. All TEM observations were made using a JEOL 1010 microscope operated at 80kV and images were captured using an Olympus SoftImaging Veleta digital camera. Surface expression of Spb1 in different GBS isolates was analyzed by enumerating the number of gold particles per cell for 40-50 cells (on one grid) and the average ±SD calculated.

2.8 Measurement of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine among GBS isolates

We used an enzyme-linked lectin-sorbent assay with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) that binds to N-acetyl D-glucosamine (NAG) and N-acetyl neuraminic acid specifically, as described elsewhere [41]. Briefly, GBS were grown in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate (Nunc, 442587) coated with 100 μg ml−1 poly-L-lysine. After washing with PBST, GBS were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for 1 hr and two-fold dilutions of 1.25 μg ml−1 peroxidase-labeled WGA (Sigma) were added. Plates were washed after 1 hr and visualized by adding 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; Sigma). Wells with THB alone, and wells with sodium azide (0.05% wt/vol; added 10 min prior to fixation) were used to estimate nonspecific binding and any influence of endogenous peroxidases. NAG-containing polysaccharide was estimated by plotting Abs 405 nm versus the logarithm of the concentration of lectin. Replicate wells (n=8) were stained with crystal violet to quantify bacterial attachment to wells [38] to compare isolates with equivalent attachment.

2.9 Measurement of Nitric Oxide and Cytokine Determination

To determine whether Spb1 affects the macrophage inflammatory response we measured nitric oxide (NO) and TNF-α, which are major components of the macrophage inflammatory response to GBS [42]. Levels of NO in cell culture supernatants were determined using the Greiss reaction [43]. Triplicate samples were assayed in duplicate and concentrations were extrapolated from a sodium nitrite standard curve. Levels of TNF-α in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA (Endogen, MA). Data shown represent mean values ± SD from one independent experiment, representative of two.

2.10 Statistical Analysis

Differences in phagocytosis and intracellular survival of GBS were compared by ANOVA, or Mann-Whitney U test for data not normally distributed or groups where equal variances not assumed (SPSS v9.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Prevalence of spb1 among GBS serotypes and RDP subtypes

Southern blotting of 163 GBS isolates indicated that 70 isolates possessed a homologue of spb1 (Table 1). In general, the presence of spb1 correlated with phylogenetic RDP subtype, but not necessarily capsular serotype. For example, all type III-3 and III-4, but no type III-1 or III-2 isolates possessed a Spb1 homologue. There were two exceptions: DNA from 1 of the 14 1b-1 isolates and 2 of the 21 V-3 isolates tested hybridized with the spb1 probe. Thus, spb1 is widely distributed among clinical GBS isolates and its presence is generally associated with particular phylogenetic RDP subtypes.

3.2 Non-opsonic phagocytosis and intracellular survival of GBS serotypes and RDP subtypes in J774A.1 macrophages

We analyzed phagocytosis of GBS as total cell-associated GBS (bound and internalized) since adherence initiates the phagocytic process leading to internalization. A mean of 4.03 ± 0.07 × 106 GBS were recovered from macrophages following the infection period (t=0 h) (Fig. 1A). Numbers of GBS phagocytosed varied up to 23-fold depending on phylogenetic type, with type III-4 having the highest number (1.83 ± 0.04 × 107) and type III-2 the lowest number (7.90 ± 0.44 × 105). Variability in phagocytosis of phylogenetic subtypes was greatest amongst serotype III isolates (23-fold, III-2 vs. III-4), whereas phagocytosis of serotype Ia (3.2-fold) and V isolates (2.6-fold) was less variable. Comparison of phagocytosis of isolates possessing spb1 with those not possessing spb1 (Fig. 1B) demonstrated that the mean number of GBS phagocytosed for subtypes possessing spb1 was significantly greater than those lacking spb1 (9.87 ± 0.7 ×106 CFU vs. 3.02 ± 0.03 × 106 CFU, p=0.03).

Figure 1. Non-opsonic phagocytosis and intracellular survival of GBS in J774A.1 macrophages.

Mean number of phagocytosed (total cell-associated: bound and internalized) GBS isolates possessing spb1 (n=7) vs. those lacking spb1 (n=10) (A), and surviving at 24 h (C); 1-3 isolates per subtype. Analysis of combined phagocytosis (B) and survival (D) data of all isolates possessing spb1 vs. those lacking spb1 showed an effect of spb1 independent of phylogenetic lineage. Data represent three independent experiments (ANOVA *p<0.05; **p<0.001). Mean phagocytosis (E) and survival (F) of GBS of spb1-possessing types (RDP Ia-1/Ia-3; n=9, and III-3/III-4; n=6) and spb1-deficient types (RDP Ia-2; n=4, and III-1/III-2; n=6). Data were analysed by Mann-Whitney U test and are representive of three independent experiments (*p<0.05).

To compare the rate of killing of GBS of different phylotypes by macrophages, the number of GBS surviving after 24 h was determined by antibiotic protection assay. A mean of 1.85 ± 0.11 × 104 viable GBS were recovered at 24 h. Recovery of viable GBS ranged from 1.44 ± 0.22 × 102 (V-2) to 4.47 ± 0.47 × 105 (III-3); a 3000-fold difference (Fig. 1C). Several isolates that were phagocytosed more efficiently had a proportionally greater number of surviving GBS at 24 h. However, this was not true for all serotypes and subtypes tested (e.g. Ia-2 and V-3 types resisted intracellular killing whereas III-4, V-2, and VIII-1 types were killed more efficiently). Comparing intracellular survival after normalizing to phagocytic uptake revealed similar trends towards lower intracellular survival of spb1-deficient strains within serotypes with the exception of GBS type Ia-2 (not shown). Overall, comparison of intracellular survival shows that the difference in uptake between spb1-possessing and -deficient isolates was maintained at 24 h (Fig. 1D) but the difference was no greater than the difference in initial uptake.

Thus, phylogenetic lineage of GBS influences both non-opsonic phagocytosis by J774A.1 macrophages and intracellular survival of GBS. Comparison of a cross-section of GBS RDP subtypes isolates possessing spb1 demonstrated that they are phagocytosed more efficiently than isolates lacking spb1.

3.3 Spb1 enhances phagocytosis of serotypes Ia and III GBS and promotes intracellular survival of serotype III GBS in J774A.1 macrophages

Serotypes Ia and III GBS are among those disproportionally associated with neonatal disease [4] and may possess or lack spb1 (Table 1). We analyzed multiple representative isolates of RDP subtypes of these serotypes that possess or lack spb1 to determine whether the presence of spb1 correlates with phagocytosis and intracellular survival. First, we compared RDP type Ia-2 isolates (lacking spb1), with type Ia-1/Ia-3 isolates possessing spb1, and type III-1/III-2 isolates (lacking spb1), with type III-3/III-4 isolates possessing spb1. The mean number of GBS of spb1-possessing RDP types Ia-1/Ia-3 phagocytosed was significantly greater compared to spb1-deficient Ia-2 isolates (p=0.045; Fig. 1E). Similarly, significantly fewer GBS of spb1-deficient RDP types III-1/III-2 were phagocytosed compared to spb1-possessing type III-3/III-4 GBS (p=0.037; Fig. 1E). The individual data points from these assays were: Phagocytosis (Table 2): RDP Ia-1/Ia-3; n=9 (log10 CFU 7.56, 7.37, 7.51, 7.31, 7.01, 7.14, 7.17, 7.19, 6.74), and III-3/III-4; n=6 (7.46, 7.38, 7.39, 7.31, 7.12, 7.26), and RDP Ia-2; n=4 (7.11, 6.39, 6.98, 7.04), and III-1/III-2; n=6 (7.37, 6.22, 7.15, 7.20, 5.90, 6.28); survival (Table 2): III-3/III-4; n=6 (5.83, 5.83, 5.50, 5.95, 5.34, 3.87), and III-1/III-2; n=6 (5.70, 3.42, 4.95, 5.32, 3.42, 3.67).

Table 2.

Phagocytosis and intracellular survival of spb1-possessing and -deficient serotype Ia and III GBS in J774A.1 macrophages according to RDP type.

| RDP type | MLST types described | Mean Phagocytosis (Log10 ± SD) | Mean Intracellular Survival (Log10 ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ia-2 | ST-23 | 6.88 ± 0.29 | 4.9 ± 0.23 |

| Ia-1/Ia-3 | ST-4,5,23/ST-7 | 7.22 ± 0.24 | 5.59 ± 0.14 |

| III-1/III-2 | ST-23,25,163/ST-19,21 | 6.68 ±0.62 | 4.41 ± 1.02 |

| III-3/III-4 | ST-17,29,31,163/ST-1 | 7.32 ± 0.11 | 5.39 ± 0.78 |

Comparing intracellular survival at 24 h, the mean number of GBS of spb1-possessing RDP types Ia-1/Ia-3 was double that of spb1-deficient type Ia-2 isolates (Fig. 1F; not statistically significant). However, the mean number of spb1-possessing type III-3/III-4 GBS surviving (4.89 ± 0.09 ×105) was significantly higher compared to spb1-deficient type III-1/III-2 GBS (7.06 ± 0.06 × 104; p=0.04; Fig. 1F). We next analyzed serotype II GBS isolates since no serotype II isolates in this study were positive for spb1 (Table 1). A mean of 5.18 ± 1.24 × 106 spb1-deficient type II GBS were phagocytosed and 4.88 × 105 survived at 24 h; numbers comparable to spb1-deficienttype III-1/III-2 and Ia-2 isolates. Thus, the presence of spb1 among multiple RDP subtypes of serotypes Ia, III, and II GBS is associated with increased non-opsonic phagocytosis, and increased intracellular survival of serotype III GBS.

RDP grouping of GBS isolates is not sufficiently discriminatory to associate phenotypes with specific isolates since isolates may harbor multiple differences in addition to Spb1. Therefore, we next compared phagocytosis and survival of WT GBS RDP III-3 strain 874391 and its spb1-deficient isogenic mutant Spb1-/tr to determine the effect of Spb1 in an otherwise identical genomic background. The truncated mutant (Spb1-/tr) was phagocytosed in significantly fewer numbers compared to GBS 874391 (p<0.04; Fig. 2A); similar results were observed in experiments using the complete deletion mutant (Spb1-/-). Moreover, significantly more GBS 874391 survived compared to isogenic spb1-deficient mutants at 24 h (p<0.05; Fig. 2B). Phagocytosis and intracellular survival of spb1-deficient mutants were restored to levels comparable to the WT by introduction of a plasmid expressing full length Spb1 in trans (Fig. 2A-B). Thus, spb1 promotes non-opsonic phagocytosis and intracellular survival of type III-3 GBS.

Figure 2. Surface expressed Spb1 promotes phagocytosis of type III-3 GBS.

Phagocytosis and survival of III-3 GBS 874391 and its truncated (Spb1-/tr) and complete deletion (Spb1-/-) mutants in J774A.1 macrophages. Fewer mutants were phagocytosed (A) and survived (B) compared to the WT strain (*p≤0.04, Mann-Whitney U test). Complementation of the deletion (Spb1trC, Spb1C) restored phagocytosis and survival phenotypes. Data shown is two independent experiments (black vs. grey 874391). SDS-PAGE of recombinant (Rc) Spb1 purified with imidazole (5–300 mM) (C; Ln 1: marker; 2-6: increasing imidazole concentrations). Immunoblots (D-F) and dot blots (G) of Spb1 in WT, spb1-deficient (Spb1-/tr, Spb1-/-), and complemented mutants (Spb1trC and Spb1C). (D) Ln 1: WT; 2: Spb1-/tr; 3: Spb1trC; 4: Rc Spb1. (E) Ln 1: WT; 2: Spb1-/tr; 3: Spb1trC; 4: Spb1-/-; 5: Spb1C; 6: Rc Spb1. (F) Ln 1: WT; 2 Rc Spb1. Immunogold TEM showing surface expression of Spb1 in WT 874391 (H-I), scale bars: 500 and 80 nM.

3.4 Expression and localization of spb1 in GBS

To analyze the expression of Spb1 in WT RDP III-3 GBS 874391 we generated a polyclonal antiserum. Recombinant Spb1 was expressed in E. coli as a soluble protein, which migrated as single band of ~50 kDa on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2C, calculated MW 50.1 kDa). Initial immunoblotting of cell wall extracts showed a major band of ~50 kDa and a ladder of higher molecular weight bands in GBS 874391 and its complemented mutant Spb1trC, which were absent in the spb1-deficient mutant (Spb1-/tr; Fig. 2D). Subsequent immunoblotting showed Spb1 expression at comparable levels in complemented strains (Spb1trC and Spb1C) and an absence of Spb1 in mutants (Fig. 2E). In our initial immunoblots Spb1 entered the resolving gel and laddering patterns were observed (Fig. 2F); subsequent blots of mutant and complemented strains showed entry of Spb1 into the resolving gel but the laddering was less prominent (Fig. 2E); heating the proteins at 75°C and use of 4-12% Criterion XT Precast Gels (Biorad, 345-0124) did not promote entry of proteins into the resolving gel nor laddering. Due to inconsistencies in western blotting we performed colony blots, which confirmed Spb1 expression patterns in WT, mutant and complemented strains (Fig. 2G). Expression of Spb1 in GBS 874391 was then analyzed by immunogold TEM using Spb1 antiserum that showed specific staining of Spb1 on the surface of the WT (Fig. 2H-I) but not in the mutants. Notably, expression of Spb1 on individual cells of GBS 874391 was highly variable; some cells expressed Spb1 around the entire surface of the cell (Fig. 2H-I), whereas other cells (within the same preparation, on one grid) expressed very little or no detectable Spb1 (not shown).

We then analyzed a collection of serotype Ia GBS RDP subtypes to determine whether surface expression of Sbp1 also varied between individual cells within a single population for these isolates. Measurement of gold particles on 40-50 individual cells of seven spb1+ Ia-1 strains (881426, 882201, 880800, 842088, 874279, 873325, 843963) and five spb1- Ia-2 strains (853817, 871922, 830467, 873843, 841557) provided average numbers of gold particles per cell for each strain, which were significantly higher for all Ia-1 strains tested compared to all Ia-2 strains (Table 3). Spb1 surface expression patterns varied considerably between individual cells within a single GBS population as observed for WT type III-3 GBS 874391. TEM panels for several type Ia-1 isolates that showed varied Spb1 surface expression patterns are given in Fig. 3A-H.

Table 3.

Quantitation of Spb1-specific gold labeling in serotype Ia GBS isolates according to RDP type.

| RDP Type | spb1 | Strain | Average No. of Spb1-specific Gold Labels Cell−1 ±SD* | Total No. of Spb1-negative Cells in a Grid Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia-1 | + | 881426 | 1.17 ±1.08 | 17/48 (35.4%) |

| + | 882201 | 1.24 ±1.95 | 12/21 (57.1%) | |

| + | 880800 | 2.44 ±1.11 | 3/48 (6.25%) | |

| + | 842088 | 2.35 ±1.56 | 5/48 (10.4%) | |

| + | 874279 | 1.35 ±1.02 | 9/48 (18.8%) | |

| + | 873325 | 2.81 ±1.53 | 4/48 (8.3%) | |

| + | 843963 | 1.48 ±0.95 | 5/48 (10.4%) | |

| Ia-2 | - | 853817 | 0.15 ±0.42 | 36/41 (87.8%) |

| - | 871922 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 43/43 (100%) | |

| - | 830467 | 0.06 ±0.24 | 31/33 (93.9%) | |

| - | 873843 | 0.13 ±0.34 | 40/46 (87.0%) | |

| - | 841557 | 0.09 ±0.60 | 44/45 (97.8%) |

spb1-possessing strains of RDP subtype 1a-1 displayed a significantly higher average number of Spb1-specific gold labels per cell compared to 1a-2 strains as measured for 40-50 individual cells within one GBS population on a single TEM grid using immunogold assay (p=0.001, all 1a-1 strains vs all 1a-2 strains, Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 3. Surface expression patterns of Spb1 on cells of type Ia-1 GBS within a single population.

High surface expression of Spb1 on some cells occurred around the entire cell surface in some Ia-1 strains (882201, A-B). In others, focal Spb1 surface expression occurred in distinct localized areas (strain 874279, C-D) or at points of intimate contact between cells (strain 842088, E-F). Regional surface expression of Spb1 around distal areas of streptococcal chains or pairs with a complete absence of labelling on other joined cells (strain 880800, G-H) was common. In some cells within a single population (on same TEM grid) no Spb1 expression was detected; inset panels show examples of these non-expressing cells. Open arrowheads indicate areas without labelling, closed arrowheads indicate areas of Spb1 labelling, all scale bars: 200 nM.

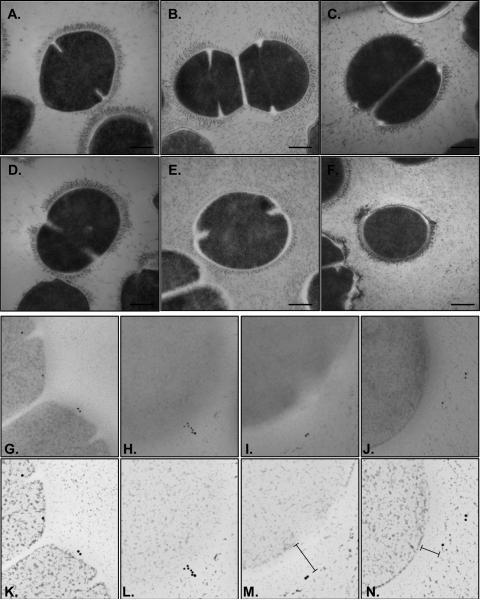

Finally, we sought to investigate the spatial distribution of Sbp1 in relation to capsular polysaccharide since capsule may influence the functional availability of Spb1 and macrophage binding. Patterns of capsule expression were characterized in GBS using modified TEM methods optimized for capsule using previously described methods [44-46] to preserve capsule structure. The findings illustrated in Figure 4A-F provide novel insight into GBS capsule architecture and highlight that major variation exists in capsule expression between different GBS cells within a single population. Capsule expression ranged from broad-based extensions of 70nm beyond the cell surface to no capsule in other areas on individual cells (Fig. 4F) and between different cells. Others cells expressed no capsule (Fig. 4B, bottom left) while some within the same population expressed a thick dense capsule around the entire cell surface (Fig. 4B). This diversity in capsule expression within a population was noted amongst all strains tested. This technique appeared to abolish the antigenicity of Spb1 during capsule stabilization because immunogold staining of these sections was unsuccessful (not shown). We therefore prepared cryosubstituted cells embedded in resin to enable immunogold staining of Spb1 on cells that would retain Spb1 antigenicity but also provide at least some information on capsule presence. In these sections Spb1 was detected at every level of capsule location starting from the base at the cell surface (Fig. 4G), throughout the capsule interior (Fig. 4H), and beyond the most outer layer of capsule (Fig. 4I-J). The sparse immunogold labels in these sections reflect the thin (60nm) preparations so the region of the capsule of each cell observed in each section is only an extremely small proportion of the entire capsule. Rendered panels of these TEM images highlight the location of Spb1 in relation to capsule (Fig. 4K-N). Collectively, these findings illustrate that major variation that exists in capsule expression between GBS cells in a population and show the scattered distribution of Spb1 throughout the layers and beyond the surface of capsule in different GBS cells.

Figure 4. Spatial location of surface expressed Spb1 relative to capsule.

Variable capsule expression in WT III-3 GBS 874391 (A), its complete Spb1-/- deletion mutant (B), and Ia-1 strains 882201 (C), 880800 (D), 874279 (E), and 842088 (F) as assessed by cryosubstitution TEM. High expression (>70nm wide) graduated down to low expression (<20nm), and often no capsule, around cell surfaces in all strains. Immunogold Spb1labeling was detected throughout the capsule location from the base at the cell surface (G), throughout the interior of the capsule (H), and beyond the outer limit of the capsule (I-J) in sections stained using a modified protocol used to retain Spb1 antigenicity. Rendered panels below highlight the location of Spb1 in relation to capsule (K-N). Scale bars, A-F are 250nm. All panels G-N are 500nm wide.

3.5 Non-opsonic phagocytosis and survival of GBS in human macrophages

Due to the possibility that responses in murine macrophages may not reflect responses in human cells we next compared murine-derived data sets with assays using human U937 HMDMs and a subset of 8 GBS isolates. GBS isolates were chosen on the basis of their phenotypes in J774A.1 cells (V-2, VIII-1) and/or RDP groupings within serotypes Ia and III. Among these isolates type III-3 (spb1-possessing) was phagocytosed most efficiently (1.58 ± 0.04 × 107) whereas type V-2 (spb1-) least efficiently (1.00 ± 1.10 × 104; Fig. 5A); type III-3 (spb1-possessing) GBS was phagocytosed significantly better compared to type III-2 GBS (spb1-), supporting a distinction between spb1-possessing and -deficient serotype III GBS isolates, as observed in murine macrophages. Phagocytosis of the V-2 isolate was signficantly lower compared to the mean phagocytosis of all the other isolates (**p<0.05), as observed in murine macrophages. Taken together, these data are consistent with J774A.1 assays, in which type III-3 and VIII-1 GBS were phagocytosed most efficiently and type V-2 least efficiently.

Figure 5. Phagocytosis and survival of GBS in U937 HMDMs.

GBS isolates that showed significant phenotypes in murine macrophages (V-2, VIII-1) and isolates of type Ia-1/2/3/4 (842088, 871922, 510012, 560249) and III-2/3 RDP groups (C44, 874391) were analyzed in phagocytosis (A) and survival assays (B) using HMDMs. Fewer GBS types III-2 and V-2 were phagocytosed and survived at 24 h vs. III-3 GBS and other isolates respectively (*p=0.002 and p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U test). Increased phagocytosis and survival of WT GBS 874391 vs. its isogenic spb1-deficient mutant Spb1-/tr was also observed in HMDMs (C; *p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U test). Data represent at least two independent experiments.

A mean of 2.00 ± 1.2 × 105 GBS were recovered from HMDMs at 24 h (Fig. 5B). Overall, differences in intracellular survival were consistent with observations in murine macrophages (compare Fig. 5B, 1C noting GBS Ia-1/2/3/4, III-2/3, V-2, VIII-1). Finally, analysis of WT GBS 874391 and its isogenic mutants demonstrated that the WT was phagocytosed and survived in HMDMs significantly better than the mutants (Fig. 5C; truncated deletion mutant shown, similar trend observed for Spb1-/-). Thus, phylogenetic background and spb1 affect non-opsonic phagocytosis and GBS survival in HMDMs.

3.6 Expression of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine in GBS isolates

Phagocytosis of GBS has been associated with the Mac-1 receptor [47], which contains lectin binding sites for saccharides including those containing NAG. We therefore analyzed NAG expression among isolates with different phagocytosis indices that possess or lack Spb1 to investigate any correlation between phagocytosis and NAG expression. We limited comparison of NAG expression among isolates to those that exhibited equivalent attachment to microtiter wells as assessed by crystal violet staining, which showed notable standard deviations (not shown). Comparing WGA binding between Spb1-deficient and Spb1-possessing isolates showed no difference in the dose response curves between the mean OD405 values of these groups (Fig. 6A). Similar comparisons between 4 Spb1-deficient isolates and 6 Spb1-possessing isolates of serotype Ia (Fig. 6B), also showed no differences in lectin binding. Analogous results were observed for serotype V isolates (Fig. 6C). Comparisons of serotype III isolates were not possible due to differences in attachment to microtiter plate wells (not shown). In control assays following adsorption of growth media OD405 values were low (mean 0.547 ±0.16) compared to blank wells with substrate alone (mean 0.390 ±0.07) indicating a low level of non-specific binding. Endogenous bacterial peroxidase production did not affect nor interfere with the assay since cultures treated with sodium azide, a cytochrome oxidase inhibitor, displayed a similar dose-response curve compared to non-treated cultures (not shown).

Figure 6. Peroxidase-linked lectin-sorbent assay with WGA for NAG analysis.

Crystal violet staining shows attachment of GBS to microtiter plate surfaces (A), and comparisons between isolates with equivalent attachment (B), or within groups of serotype Ia (C), or V (D) isolates with equivalent attachment, showed no correlation between NAG expression and phagocytosis. Data represent mean values ± SD of one independent experiment representative of two experiments.

3.7 Macrophage activation by GBS occurs independently of Spb1

Phagocytosis of GBS triggers expression of nitric oxide (NO) and TNF-α, markers of macrophage activation [42]. Thus, we compared NO and TNF-α induced by WT GBS 874391 and its spb1-deficient Spb1-/tr mutant to determine if increased GBS phagocytosis and survival was associated with macrophage activation. However, secretion of NO and TNF-α by J774A.1 macrophages infected with the Spb1-/tr mutant did not differ significantly compared to WT (Fig. 7A-B). In U937 HMDMs the responses to WT GBS versus the Spb1-/tr mutant were slightly increased, but not statistically significant (Fig. 7C-D). Neither NO nor TNF-α were detected in supernatants of uninfected macrophages. Thus, Spb1 does not significantly impact the macrophage NO and TNF-α response.

Figure 7. Production of NO and TNF-α in macrophages infected with GBS 874391 and its spb1-deficient mutant.

Shown is the mean ± SEM concentration of nitrite (A) and TNF-α (B) in supernatants of J774A.1 (A, C) and HMDMs (B, D) infected with WT GBS 874391 and it's spb1-deficient mutant (no significant differences; Spb1-/tr mutant shown). Data represent triplicate samples from one independent experiment, representative of two.

4. DISCUSSION

The efficiency at which macrophages phagocytose and kill GBS in the absence of opsonins is critical in early defense against this pathogen. Capsule modulates GBS phagocytosis [47, 48], however, the role of surface proteins such as Spb1 in nonopsonic phagocytosis is less understood. Here, we demonstrate that the GBS invasin, Spb1, enhances the efficiency of non-opsonic macrophage phagocytosis and confers a survival advantage inside macrophages. These effects appear to be independent of NAG expression and inflammation comprising NO and TNF-α responses. Most of the experiments in this study used J774A.1 macrophages with confirmatory assays in HMDMs for only a few selected GBS isolates. This is a limitation of the current study since observations in J774A.1 cells may not apply to other macrophage cell lines. Moreover, although our findings are consistent with those recently reported by Maisey et al. [29] the degree of effect imparted by the pilus protein in our macrophage phagocytosis and intracellular survival assays is notably lower.

The majority of GBS isolates possessing spb1 in our study were phagocytosed more efficiently than isolates without Spb1, and serotype Ia and III isolates that possessed spb1 were phagocytosed more efficiently compared to serotype-matched RDP-paired isolates lacking spb1. However, RDP comparisons are not sufficiently discriminatory to assign phenotypes to isolates given the large size of the GBS pangenome [49]. In this regard our use of isogenic spb1-deficient mutants confirmed the impact of Spb1 in the absence of other variables. These assays confirmed that spb1-deficient type III-3 GBS is phagocytosed less efficiently compared to its parent spb1-possessing GBS. Prior reports that have shown that trypsin treatment of GBS inhibits opsonin-independent phagocytosis support the notion that protein ligands such as Spb1 are important in these interactions [50, 51]. In the case of Spb1 the protein may act directly as a ligand for non-opsonic receptor-mediated phagocytosis as suggested elsewhere [29]; it may also influence macrophage binding to other GBS structures. Immunogold-based electron microscopy revealed variable surface expression of Spb1 is between cells in a given population and this has implications for understanding pilus expression in GBS. Whether regulation of pilus expression differs between cells remains unknown. In a broader sense these findings may be reflective of a potential for lifestyle adaption in GBS analogous to Gram-negative bacteria where expression of fimbriae in cells varies under different environmental conditions to enable fitness traits for different niches.

Measurement of intracellular survival showed that spb1 promotes GBS survival following non-opsonic phagocytosis. Intracellular survival was significantly compromised amongst a collection of spb1-deficient type III isolates and was confirmed using GBS 874391 and its isogenic spb1-deficient mutants. Although a similar phenomenon has been described for N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (NAG), which promotes GBS uptake and intracellular survival [51], in this study, NAG expression did not correlate with phagocytosis among the isolates analyzed. Our detailed analysis of Sbp1 in relation to capsule by TEM offers revealing insight into its functional availability and presence beyond the capsule where it could bind to other molecules. A high degree of variability in capsule expression within and between GBS cells in a given population suggests that capsule would influence the availability of Spb1. These findings also offer new understanding of capsule expression in GBS, which in addition to switching and gene transfer events described previously [52, 53] may impact the lifestyle of GBS in the host environment. This observations on Spb1 in relation to GBS capsule require further investigation. The ability of Spb1 to augment survival was not however, associated with macrophage responses related to TNF-α and NO release. Thus, the molecular mechanism by which Spb1 promotes intracellular survival of GBS, which appears to influence disease pathogenesis as suggested elsewhere [29] is unknown. Enhanced phagocytosis and intracellular survival would allow GBS to evade other components of host immunity such as neutrophils, specific opsonic recognition, and complement. In infected patients, bacterial survival in an intracellular niche such as macrophages could avoid exposure of GBS to antibiotics. Finally, the positive effect of Spb1 on intracellular survival inside macrophages may represent a novel interventional target that could be investigated to improve the intracellular killing of GBS in these cells.

This study demonstrates that opsonin-independent phagocytosis and intracellular survival of GBS depends on phylogenetic background and spb1. Spb1 might represent a target for intervention aimed at improving phagocytic killing after bacterial recognition. Future studies should focus on mechanisms by which Spb1 achieves these functions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported with grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (455901, 569674), National Institutes of Health (ROI AI40918 and P30 CA21765), the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, the Thrasher Research Fund, Griffith University, and an Australian Academy of Sciences Fellowship (G.C.U.). The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable input of Shaynoor Dramsi at Institut Pasteur for enabling GBS mutant construction, technical advice, and for excellent critical review of the manuscript. We thank April Whiting of University of Utah, and Feng Ying C. Lin of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health for assistance with isolate collection and provision of some isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker CJ. Group B Streptococcal infections. In: Stevens DL, Kaplan EL, editors. Streptococcal Infections. Clinical aspects, microbiology, and molecular pathogenesis. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 222–237. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker CJ, Barrett FF. Transmission of group B streptococci among parturient women and their neonates. J Pediatr. 1973;83:919–925. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrieri P, Cleary PP, Seeds AE. Epidemiology of group-B streptococcal carriage in pregnant women and newborn infants. J Med Microbiol. 1977;10:103–114. doi: 10.1099/00222615-10-1-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards MS, Baker CJ. Group B streptococcal infections in elderly adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:839–847. doi: 10.1086/432804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulett KB, Benjamin WH, Jr., Zhuo F, Xiao M, Kong F, Gilbert GL, Schembri MA, Ulett GC. Diversity of group B streptococcus serotypes causing urinary tract infection in adults. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2055–2060. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00154-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker CJ, Kasper DL. Correlation of maternal antibody deficiency with susceptibility to neonatal group B streptococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:753–756. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604012941404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker CJ, Rench MA, Edwards MS, Carpenter RJ, Hays BM, Kasper DL. Immunization of pregnant women with a polysaccharide vaccine of group B streptococcus. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1180–1185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811033191802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards MS. Complement in neonatal infections: an overview. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986;5:S168–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fettucciari K, Rosati E, Scaringi L, Cornacchione P, Migliorati G, Sabatini R, Fetriconi I, Rossi R, Marconi P. Group B Streptococcus induces apoptosis in macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165:3923–3933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman MP, Johnson JT, Rothlein R, Hughes BJ, Smith CW, Anderson DC. Role of pulmonary phagocytes in host defense against group B streptococci in preterm versus term rabbit lung. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:818–826. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornacchione P, Scaringi L, Fettucciari K, Rosati E, Sabatini R, Orefici G, von Hunolstein C, Modesti A, Modica A, Minelli F, Marconi P. Group B streptococci persist inside macrophages. Immunology. 1998;93:86–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulett GC, Bohnsack JF, Armstrong J, Adderson EE. Beta-hemolysin-independent induction of apoptosis of macrophages infected with serotype III group B streptococcus. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1049–1053. doi: 10.1086/378202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valenti-Weigand P, Benkel P, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS. Entry and intracellular survival of group B streptococci in J774 macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2467–2473. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2467-2473.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulett GC, Maclean KH, Nekkalapu S, Cleveland JL, Adderson EE. Mechanisms of group B streptococcal-induced apoptosis of murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175:2555–2562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulett GC, Adderson EE. Regulation of Apoptosis by Gram-Positive Bacteria: Mechanistic Diversity and Consequences for Immunity. Current Immunology Reviews. 2006;2:119–141. doi: 10.2174/157339506776843033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemming VG, McCloskey DW, Hill HR. Pneumonia in the neonate associated with group B streptococcal septicemia. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130:1231–1233. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1976.02120120065011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuchat A. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:497–513. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones N, Bohnsack JF, Takahashi S, Oliver KA, Chan MS, Kunst F, Glaser P, Rusniok C, Crook DW, Harding RM, Bisharat N, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing system for group B streptococcus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2530–2536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2530-2536.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musser JM, Mattingly SJ, Quentin R, Goudeau A, Selander RK. Identification of a high-virulence clone of type III Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) causing invasive neonatal disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4731–4735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi S, Detrick S, Whiting AA, Blaschke-Bonkowksy AJ, Aoyagi Y, Adderson EE, Bohnsack JF. Correlation of phylogenetic lineages of group B Streptococci, identified by analysis of restriction-digestion patterns of genomic DNA, with infB alleles and mobile genetic elements. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1034–1038. doi: 10.1086/342950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohnsack JF, Takahashi S, Detrick SR, Pelinka LR, Hammitt LL, Aly AA, Whiting AA, Adderson EE. Phylogenetic classification of serotype III group B streptococci on the basis of hylB gene analysis and DNA sequences specific to restriction digest pattern type III-3. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1694–1697. doi: 10.1086/320717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Kong F, Zhao Z, Gilbert GL. Comparison of a 3-set genotyping system with multilocus sequence typing for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus) J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4704–4707. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4704-4707.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming KE, Bohnsack JF, Palacios GC, Takahashi S, Adderson EE. Equivalence of high-virulence clonotypes of serotype III group B Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:505–508. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohnsack JF, Whiting AA, Bradford RD, Van Frank BK, Takahashi S, Adderson EE. Long-range mapping of the Streptococcus agalactiae phylogenetic lineage restriction digest pattern type III-3 reveals clustering of virulence genes. Infect Immun. 2002;70:134–139. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.134-139.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adderson EE, Takahashi S, Wang Y, Armstrong J, Miller DV, Bohnsack JF. Subtractive hybridization identifies a novel predicted protein mediating epithelial cell invasion by virulent serotype III group B Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6857–6863. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6857-6863.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brochet M, Couve E, Zouine M, Vallaeys T, Rusniok C, Lamy MC, Buchrieser C, Trieu-Cuot P, Kunst F, Poyart C, Glaser P. Genomic diversity and evolution within the species Streptococcus agalactiae. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1227–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosini R, Rinaudo CD, Soriani M, Lauer P, Mora M, Maione D, Taddei A, Santi I, Ghezzo C, Brettoni C, Buccato S, Margarit I, Grandi G, Telford JL. Identification of novel genomic islands coding for antigenic pilus-like structures in Streptococcus agalactiae. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:126–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dramsi S, Caliot E, Bonne I, Guadagnini S, Prevost MC, Kojadinovic M, Lalioui L, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P. Assembly and role of pili in group B streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1401–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maisey HC, Quach D, Hensler ME, Liu GY, Gallo RL, Nizet V, Doran KS. A group B streptococcal pilus protein promotes phagocyte resistance and systemic virulence. FASEB J. 2008;22:1715–1724. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-093963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lalioui L, Pellegrini E, Dramsi S, Baptista M, Bourgeois N, Doucet-Populaire F, Rusniok C, Zouine M, Glaser P, Kunst F, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P. The SrtA Sortase of Streptococcus agalactiae is required for cell wall anchoring of proteins containing the LPXTG motif, for adhesion to epithelial cells, and for colonization of the mouse intestine. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3342–3350. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3342-3350.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhoeckx KC, Bijlsma S, de Groene EM, Witkamp RF, van der Greef J, Rodenburg RJ. A combination of proteomics, principal component analysis and transcriptomics is a powerful tool for the identification of biomarkers for macrophage maturation in the U937 cell line. Proteomics. 2004;4:1014–1028. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause SW, Rehli M, Kreutz M, Schwarzfischer L, Paulauskis JD, Andreesen R. Differential screening identifies genetic markers of monocyte to macrophage maturation. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:540–545. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron ML, Granger DL, Weinberg JB, Kozumbo WJ, Koren HS. Human alveolar and peritoneal macrophages mediate fungistasis independently of L-arginine oxidation to nitrite or nitrate. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1313–1319. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneemann M, Schoedon G, Hofer S, Blau N, Guerrero L, Schaffner A. Nitric oxide synthase is not a constituent of the antimicrobial armature of human mononuclear phagocytes. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1358–1363. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMichael JC, Ou JT. Structure of common pili from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:969–975. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.969-975.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collinson SK, Emody L, Muller KH, Trust TJ, Kay WW. Purification and characterization of thin, aggregative fimbriae from Salmonella enteritidis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4773–4781. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4773-4781.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson DL, White AP, Rajotte CM, Kay WW. AgfC and AgfE facilitate extracellular thin aggregative fimbriae synthesis in Salmonella enteritidis. Microbiology. 2007;153:1131–1140. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/000935-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulett GC, Mabbett AN, Fung KC, Webb RI, Schembri MA. The role of F9 fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in biofilm formation. Microbiology. 2007;153:2321–2331. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/004648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allsopp LP, Totsika M, Tree JJ, Ulett GC, Mabbett AN, Wells TJ, Kobe B, Beatson SA, Schembri MA. UpaH is a newly identified autotransporter protein that contributes to biofilm formation and bladder colonization by uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1659–1669. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01010-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valle J, Mabbett AN, Ulett GC, Toledo-Arana A, Wecker K, Totsika M, Schembri MA, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. UpaG, a new member of the trimeric autotransporter family of adhesins in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4147–4161. doi: 10.1128/JB.00122-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leriche V, Sibille P, Carpentier B. Use of an enzyme-linked lectinsorbent assay to monitor the shift in polysaccharide composition in bacterial biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1851–1856. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.1851-1856.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ulett GC, Adderson EE. Nitric oxide is a key determinant of group B streptococcus-induced murine macrophage apoptosis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1761–1770. doi: 10.1086/429693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuehr DJ, Kwon NS, Gross SS, Thiel BA, Levi R, Nathan CF. Synthesis of nitrogen oxides from L-arginine by macrophage cytosol: requirement for inducible and constitutive components. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:420–426. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammerschmidt S, Wolff S, Hocke A, Rosseau S, Muller E, Rohde M. Illustration of pneumococcal polysaccharide capsule during adherence and invasion of epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4653–4667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4653-4667.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nixon SJ, Webb RI, Floetenmeyer M, Schieber N, Lo HP, Parton RG. A single method for cryofixation and correlative light, electron microscopy and tomography of zebrafish embryos. Traffic. 2009;10:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graham LL, Harris R, Villiger W, Beveridge TJ. Freeze-substitution of gram-negative eubacteria: general cell morphology and envelope profiles. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1623–1633. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1623-1633.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albanyan EA, Edwards MS. Lectin site interaction with capsular polysaccharide mediates nonimmune phagocytosis of type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5794–5802. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5794-5802.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antal JM, Cunningham JV, Goodrum KJ. Opsonin-independent phagocytosis of group B streptococci: role of complement receptor type three. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1114–1121. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1114-1121.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Donati C, Medini D, Ward NL, Angiuoli SV, Crabtree J, Jones AL, Durkin AS, Deboy RT, Davidsen TM, Mora M, Scarselli M, Margarit y Ros I, Peterson JD, Hauser CR, Sundaram JP, Nelson WC, Madupu R, Brinkac LM, Dodson RJ, Rosovitz MJ, Sullivan SA, Daugherty SC, Haft DH, Selengut J, Gwinn ML, Zhou L, Zafar N, Khouri H, Radune D, Dimitrov G, Watkins K, O'Connor KJ, Smith S, Utterback TR, White O, Rubens CE, Grandi G, Madoff LC, Kasper DL, Telford JL, Wessels MR, Rappuoli R, Fraser CM. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagao PE, Costa e Silva-Filho F, Benchetrit LC, Barrucand L. Cell surface hydrophobicity and the net electric surface charge of group B streptococci: the role played in the micro-organism-host cell interaction. Microbios. 1995;82:207–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monteiro GC, Hirata R, Jr., Andrade AF, Mattos-Guaraldi AL, Nagao PE. Surface carbohydrates as recognition determinants in non-opsonic interactions and intracellular viability of group B Streptococcus strains in murine macrophages. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cieslewicz MJ, Chaffin D, Glusman G, Kasper D, Madan A, Rodrigues S, Fahey J, Wessels MR, Rubens CE. Structural and genetic diversity of group B streptococcus capsular polysaccharides. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3096–3103. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3096-3103.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martins ER, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M. Evidence for rare capsular switching in Streptococcus agalactiae. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1361–1369. doi: 10.1128/JB.01130-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.