Abstract

Protein quality control (proteostasis) depends on constant protein degradation and resynthesis, and is essential for proper homeostasis in systems from single cells to whole organisms. Cells possess several mechanisms and processes to maintain proteostasis. At one end of the spectrum, the heat shock proteins modulate protein folding and repair. At the other end, the proteasome and autophagy as well as other lysosome-dependent systems, function in the degradation of dysfunctional proteins. In this review, we examine how these systems interact to maintain proteostasis. Both the direct cellular data on heat shock control over autophagy and the time course of exercise-associated changes in humans support the model that heat shock response and autophagy are tightly linked. Studying the links between exercise stress and molecular control of proteostasis provides evidence that the heat shock response and autophagy coordinate and undergo sequential activation and downregulation, and that this is essential for proper proteostasis in eukaryotic systems.

Keywords: autophagy, exercise, heat shock response, HSP70, humans, protein breakdown, protein synthesis

Abbreviations: AKT, v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; ATG, autophagy-related; BECN1, Beclin 1, autophagy related; EIF4EBP1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FOXO, forkhead box O; HSF1, heat shock transcription factor 1; HSP, heat shock protein; HSPA8/HSC70, heat shock 70kDa protein 8; IL, interleukin; LC3, MAP1LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; MTMR14/hJumpy, myotubularin related protein 14; MTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; NR1D1/Rev-Erb-α, nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PPARGC1A/PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 α; RHEB, Ras homolog enriched in brain; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SQSTM1/p62, sequestosome 1; TPR, translocated promoter region, nuclear basket protein; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; ULK1, unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1

Introduction

Protein quality control is fundamental to intracellular homeostasis. Central to this quality is a balance between protein folding and protein degradation, the former controlled by cellular chaperones of the heat shock response,1 and the latter by the ubiquitin-proteasome system,2 autophagy,3 and other lysosome-dependent systems.4 Recent data support the idea that these systems influence each other.5,6 Existing in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the heat shock protein chaperone system of protein folding and assembly as well as regulation of degradation of denatured proteins is more evolutionarily ancient7 compared to autophagy, which is exclusively a eukaryotic process. Given the greater evolutionary age of the heat shock system compared to autophagy, as well as the fact that the heat shock protein response functions in both protein conservation and degradation, a question arises of whether and how they are coordinated. Recent data5 provide support for the idea that heat shock response does, in fact, exert control over autophagy.

Exercise results in widespread protein degradation followed by a similarly large scale building phase.8 Thus, exercise can be used to follow the cross-regulation of protein breakdown and rebuilding, including novel regulatory paths that might exist. We propose that there is such a novel, previously unappreciated regulated crosstalk between heat shock-governed protein synthesis and folding and the protein degradation state driven by autophagy. In this review, by using the complex stress of exercise, we will discuss the model of cooperation between autophagy and heat shock response and highlight evidence suggesting an interaction and control between those 2 systems.

Basic concepts

The role of autophagy and heat shock response in protein homeostasis

To be fully functional, proteins, after translation, fold into the correct 3-dimensional structure. In the crowded intracellular environment with a high risk of aggregation, a protein requires assistance to assume its native and functionally physiological conformation and avoid hydrophobic tangles, precipitation, and inappropriate protein interactions. In addition, intracellular problems (spontaneous transcriptional and translational errors, sudden increase in protein synthesis or excess of synthesized subunits, incorrect cellular localization, or the damaging effect of highly reactive free radicals) as well as extracellular stressors (high temperature, hypoxia, radiation, toxic chemicals, endotoxins, and osmotic pressure) can alter the folding capacity of a cell leading to translational arrest as well as the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins.9-14

To insure protein homeostasis, cells employ several systems. These include intracellular removal or processing of misfolded proteins,15 involving cellular chaperones, the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and autophagy. Intracellular or pericellular processing of abnormal proteins is a simple way of protein elimination, but if not controlled properly, may lead to cell death, dysregulation of homeostasis, and diseases such as Huntington,16 amyloidosis,17 Alzheimer,18 or Parkinson.19 The ubiquitin-proteasome system deals primarily with endogenous proteins. In this process, the poly-ubiquitin-protein complex binds to the regulatory unit of the proteasome, which unfolds and translocates the substrate proteins into the central chamber for proteolytic digestion.20

At basal levels or stress conditions, eukaryotic cells employ autophagy to remove misfolded proteins, large protein aggregates, and whole damaged organelles inaccessible to smaller proteolytic systems.21 Under starvation conditions, autophagy represents an effective physiological response providing a biofuel from degraded macromolecules to maintain sufficient ATP production for adaptive macromolecular synthesis to survive stressful conditions.22 There are 3 primary types of autophagy: chaperone-mediated autophagy, microautophagy, and macroautophagy. In chaperone-mediated autophagy, cytosolic proteins with a signature exposed pentapeptide motif (KFERQ)23,24 are targeted by HSPA8/HSC70 (heat shock 70 kDa protein 8). After motif recognition by HSPA8 and subsequent binding to LAMP2A (lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2A), target proteins undergo unfolding and translocate into the lysosomal lumen where they are degraded.25 During microautophagy, a small invagination of the lysosomal membrane sequestering cytosolic content is formed. After pinching off into the lysosomal lumen, the vacuole is degraded.26 Macroautophagy (referred to hereafter as autophagy) can also be subdivided into several main stages. During the initial step, double- or multimembrane autophagic vacuoles called autophagosomes are formed by engulfing a portion of the cytoplasm or a damaged organelle.27,28 Next, the autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes forming autolysosomes that degrade the captured material.27,29,30

Whereas autophagy is ubiquitous in eukaryotic cells,31 the heat shock protein (HSP) chaperone system is a feature of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. All living organisms employ the HSP system to convert nascent proteins into their native conformation7 and to mediate the degradation of irreversibly denatured proteins that accumulate in the cells in response to various stressors. Thus, autophagy and the heat shock response represent 2 functionally distinct systems of cellular protein quality control. Under cellular stress conditions, these 2 systems are likely to complement each other. A recent study5 provided evidence that cells under certain conditions prioritize the HSP response over autophagy, and the heat shock response inhibits autophagy under conditions when both systems are activated.

The role of autophagy in physiology of skeletal muscle

Growing evidence suggests that the right level of autophagy, along with the ubiquitin-proteasome system, is critical to homeostasis of skeletal muscle.32 Two main approaches focusing on activation or inhibition of autophagy have been undertaken to delineate the role of autophagy in regulating the physiology of skeletal muscle.

Inhibition of autophagy in autophagy-related (ATG) 5 and ATG7 conditional knockout mice models leads to a small reduction in body growth, degenerative changes in muscle tissue, reduction in myofiber size, accumulation of protein aggregates, abnormal mitochondria, and reduction in muscle force leading to severe weakness.33,34 Similarly, reduced autophagy in col6a−/−/collagen VI-deficient mice results in the accumulation of dysfunctional organelles and promotes apoptosis and muscle atrophy.35 Mutant mice with normal levels of basal autophagy but deficient in exercise- or starvation-induced autophagy show lower endurance, impaired glucose metabolism, and inhibited glucose uptake by skeletal muscle after a single bout of exercise. Moreover, the autophagy mutant mice lack chronic exercise-induced protection against glucose intolerance when fed a high-fat diet.36 The importance of autophagy in the development of endurance capacity was further demonstrated in becn1 (VPS30/ATG6) heterozygous mice showing reduced basal autophagy flux, number of mitochondria, and capillary density in skeletal muscle.37 Interestingly, diminished autophagy levels in sedentary Becn1 heterozygotes does not influence the exercise performance when compared with wild-type animals, but completely prevents the development of muscle adaptation and physical endurance in response to several weeks of involuntary training among Becn1 heterozygotes. To sum up, these studies demonstrate that autophagy plays a fundamental role in skeletal tissue homeostasis and, when deficient, leads to impaired physical performance.

Recent studies have also shown that aggravated autophagy contributes to muscle loss. In mice, activation of the FOXO (forkhead box O) transcription factors results in enhanced autophagy and lysosomal proteolysis leading to muscle atrophy.38,39 Similarly, increased autophagy levels in a transgenic mouse model expressing a mutant Sod1 (superoxide dismutase 1, soluble) gene that mediates antioxidative defense are associated with muscle atrophy and a profound reduction in muscle strength.40 In centronuclear myopathy, a naturally occurring mutation leading to inactivation of MTMR14/hJumpy (myotubularin-related protein 14) activates autophagy, suggesting that aggravated autophagy is important in the etiology of centronuclear myopathy.41 Excessive autophagy contributing to muscle wasting has also been shown in tumor-bearing animals,42 in a systemic burn injury model in mice,43 in patients with progressive stages of lung cancer cachexia,44 and in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients.45

These studies suggest that aggravated/excessive autophagy is responsible for the loss of muscle mass, whereas defective autophagy leads to the degeneration of muscle fiber, severe reduction in muscle strength, and metabolic disorders. Future studies are needed to clearly define the role of autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology in skeletal muscle. In addition, identifying potential and effective therapeutic approaches focusing on autophagy management in disease should be a priority of the upcoming research.

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of autophagy

Metabolic adaptations are primarily mediated by AMPK (adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase) and AKT/protein kinase B (v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog),46,47 and both are important in autophagy regulation. AMPK controls food intake in the hypothalamus, promotes glucose and fatty acid uptake and oxidation in heart and skeletal muscle, inhibits fatty acid synthesis in adipocytes and liver, and inhibits insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells.48,49 AKT regulates cellular metabolism through glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, glycolysis, and protein synthesis.50

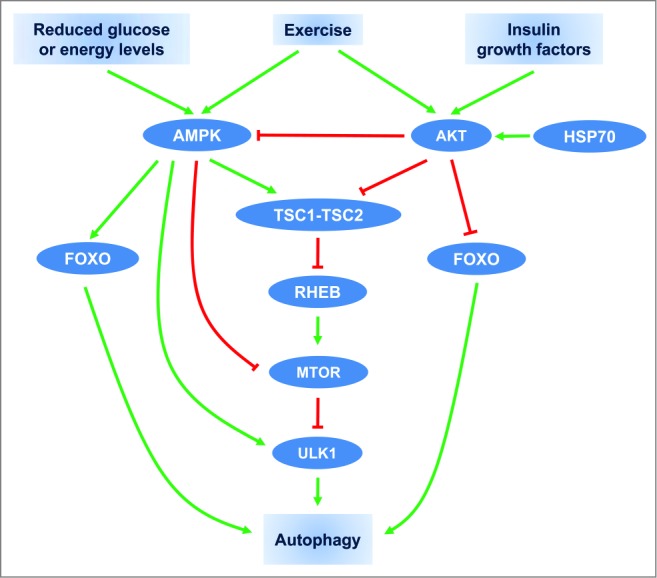

Prolonged exercise, a physiological condition represented by high energy requirements, activates both AMPK51-53 and AKT,54,55 that modulate the activity of TSC (tuberous sclerosis complex) consisting of the TSC1-TSC2 tumor suppressor heterodimer that is involved in autophagy regulation (Fig. 1). Downstream of TSC, a small protein, the RAS-like GTPase RHEB (Ras homolog enriched in brain), cycles between an active GTP-bound form and an inactive GDP-bound form.56 Reduced glucose or energy levels increase the AMP/ATP ratio and results in the activation of AMPK and TSC.49 This activation of AMPK and TSC leads to augmentation of the RHEB-GDP levels, inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) pathway and leads to inhibition of cell growth and activation of autophagy.46,48,49 In contrast, activated AKT directly phosphorylates TSC2 and inhibits its function.57 Reduced activity of TSC2 by AKT increases RHEB-GTP levels resulting in MTOR activation58,59 and autophagy inhibition. Additionally, AKT may also activate the MTOR pathway by the inhibition of AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of TSC247 and AMPK may inhibit MTOR directly by modulating its phosphorylation site.60-62 Moreover, direct physical interaction between AMPK or MTOR and ULK1 (unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1) plays a crucial role in the regulation of mammalian autophagy.63-69 Under conditions of nutrients abundance, the activated MTOR phosphorylates ULK1 and prevents its interaction with AMPK. Conversely, under starvation conditions, AMPK-induced MTOR inhibition prevents MTOR from binding to ULK1. Subsequently, AMPK directly interacts with and phosphorylates ULK1 resulting in its activation and leading to autophagy initiation.65 As suggested recently, this complex modulation of ULK1 activity by AMPK and MTOR may represent the regulation of autophagy and metabolism accordingly to the availability of glucose and amino acids.63

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of autophagy regulation by exercise, hormonal, and nutrient signals. Arrow-headed (green) lines and bar-headed (red) lines indicate activation and inhibition, respectively.

In addition to the MTOR pathway, AMPK and AKT have been reported to control glucose metabolism and autophagy through modulation of FOXO family transcription factors. AMPK through the transcriptional activation of Foxo3/Foxo3a suppresses gluconeogenesis in the liver.70 Interestingly, it has been recently shown that exercise-induced AKT phosphorylation suppresses the hepatic gluconeogenesis through a decreased association between FOXO1 and PPARGC1A/PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 α).71 In addition, AKT activation suppresses FOXO3 activation and autophagy independently of MTOR.39 Conversely, AMPK triggers autophagy in skeletal muscle through activation of FOXO3 and interaction with ULK1.72 We have shown that HSP70 exerts its inhibitory effect on autophagy via the increased AKT pathway.5 To sum up, AMPK and AKT are responsible for controlling metabolic equilibrium and play a critical role in modulating skeletal muscle mass through fine adjustments of protein expression. Future studies are required to delineate the role of HSP70 and other members of the heat shock response on intracellular targets involved in autophagy regulation under physiological and pathological conditions.

A correspondence between immune and muscle cells

Glucose is an important nutrient for contracting muscle.73 During exercise glucose uptake rises significantly and reaches a peak (41% of glucose contribution in muscle metabolism) at 90 min during exercise.74 This initial glucose involvement is replaced by free fatty acids whose contribution of total muscle metabolism extends to 62% at 240 min of exercise.74 Muscle tissue is the main glutamine depot containing 90% of the body's glutamine reserves and during catabolic stress in humans, muscles are a primary organ of glutamine synthesis and release to the blood.75,76 Glutamine is the most abundant free amino acid in the body and it is critical for the proper functioning of the immune cells that utilize it at high rates for antigen presentation and cytokines production.77,78 In addition, macrophage-derived cytokine stimulates glutamine synthesis in muscle cells.79 This loop of interaction between cytokines and glutamine represents cooperation and codependence between muscle and the immune system. Another link involving the immune system and insulin target cells (muscle) has been demonstrated in the development of metabolic syndrome. In this model, an attenuated autophagy by fatty acid in macrophages leads to activation and release of inflammasome and proinflammatory cytokine IL1B/IL-1β that in turn inhibits normal insulin signaling in liver, adipose, and muscle tissues resulting in insulin resistance.80

Cooperation between heat shock response and autophagy during heat stress and the unfolded protein response

Heat stress response modulates autophagy

Heat stress denatures proteins and alters translation. It is also a potent stimulus of the heat shock response. Thus, it is not surprising that heat exerts a complex effect on autophagy. In one of the earliest studies describing the effect of a physiologically relevant increase in temperature on autophagy induction in isolated rat hepatocytes, the highest autophagy levels were detected at 37°C reflecting the normal body temperature, whereas temperature elevation to 40°C reduced the autophagic sequestration.81 Later, by utilizing different cellular techniques and models, it was shown that heat stress, as high as 43°C, induces autophagy.82 Heat exposure also triggers autophagy in a human hepatoma cell line,83 rat cardiomyocytes,84 human alveolar basal epithelial cells,5 a mouse spermatocyte cell line,85 and human cervical cancer cells.86 Moreover, recent studies have shown that deletion of the heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1), increases basal autophagy levels.5 Treatment with a constitutively active HSF1 mutant inhibits the basal level of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3-II) protein and prevents induction of autophagy in heat-treated cells.82

In animals, similar to cell culture studies, heat exposure upregulates autophagy proteins in the rat cerebellar Purkinje cells87 and hepatocytes,88 but not in the pancreatic cells.89 These studies suggest that autophagy remains under regulatory control of the heat shock response, but more studies are needed to fully define the hierarchy of importance among proteins involved in autophagy regulation.

Interactions between the heat shock response and autophagy during the unfolded protein response

Besides hyperthermia, conditions generating the unfolded protein response upregulate both the heat stress response and autophagy. Treatment with a highly selective, reversible inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, bortezomib, resulting in mitochondrial dysregulation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress triggers autophagy and the cellular chaperone HSP70 in melanoma cell lines.90 Similarly, exposure to the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat activates the heat stress response and ER stress and leads to an increased accumulation of unfolded proteins resulting in autophagy induction.91 In 2 independent cell culture studies, HSP70 and HSF1 were shown to be required in autophagosomes formation. In mouse embryonic fibroblasts, panobinostat-induced formation of autophagic vesicles was prevented by HSP70 knockout,92 whereas, in human breast adenocarcinoma cells, exposure to the chemotherapeutic agent carboplatin increased autophagy as indicated by an increase in LC3 punctate structures and LC3 and ATG7 protein expression that was prevented by knockdown of HSF1.93 It was also reported that silencing of TPR (translocated promoter region, nuclear basket protein) a component of the nuclear pore complex leading to a significant reduction in nuclear pore numbers results in a significant increase in autophagy that is associated with an increase in heat stress response in HeLa cells (see a comprehensive diagram illustrating the intracellular mechanisms regulating autophagy in translocated promoter region, nuclear basket protein-depleted cells).94 In mouse with progression of Alzheimer-like deficits, the autophagy-activating agent rapamycin (an inhibitor of MTOR) results in HSF1 activation and HSPs overexpression in the brain. Rapamycin-fed animals express a reduced amyloid-β content in the brain, demonstrating that rapamycin treatment improves protein homeostasis by removing damaged proteins through autophagy and fixing unfolded proteins via increased chaperone activity.95 Although the exact role and relationship between autophagy and the heat stress response under stressful conditions remains to be determined, they cooperate in maintaining cellular homeostasis by facilitating appropriate folding of partially unfolded proteins or removing irreversibly damaged proteins to help the cell in coping with the cellular stress.86,88,96

Cooperation between the heat shock response and autophagy during exercise in animals and in humans

The effect of exercise on muscle growth

Muscle growth is only possible when protein synthesis exceeds protein breakdown, meaning there is a positive anabolism. Resistance exercise is important and well known in development of muscle mass (hypertrophy). In humans, resistance exercise increases protein synthesis97-106 and improves protein balance during the recovery phase in the skeletal muscle,8,107,108 but not during acute bouts of resistance exercise.109 Similar to resistance exercise, low intensity aerobic training110 causes a significant increase in fractional synthetic rate in the leg muscle. In contrast, in female deltoid muscle, neither resistance nor swimming exercise, when performed separately, had a significant effect on net muscle protein synthesis, but when combined stimulated increased muscle protein synthesis above baseline levels.111 Similarly, there was no change in protein synthesis or protein breakdown in vastus lateralis shortly after an acute bout of resistance exercise.112 Interestingly, the effect of exercise on protein synthesis seems to depend on the type, or protein measurement (mixed vs. myofibrillar), and training status of the subjects (trained vs. untrained). In response to acute resistance exercise, there was a significant increase in mixed protein synthesis in untrained subjects but not in the trained athletes:113 however, the myofibrillar protein synthesis rate was elevated in both untrained and trained subjects in response to resistance exercise.114,115

The effect of the training protocol and muscle protein synthesis is documented in exercise literature as well. Both resistance116-118 and endurance119 exercise training result in a marked increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis rate. However, a 12-wk regimen of high-intensity resistance exercise did not alter the whole body protein synthesis.120

The role of autophagy and other lysosome systems in exercise-induced muscle growth remains to be determined.

Exercise and HSP70 protein expression in animals

Heat shock proteins comprise a family of chaperones, whose expression is induced in response to a wide variety of physiological and environmental insults, including high temperature, oxidative stress, heavy metal exposure, and ionizing radiation.121-123 The primary function of these heat shock proteins is to fold nascent proteins and refold denatured proteins after cellular stress.7,124,125 The heat shock proteins also modulate physiology of a single cell or whole organism by regulating signaling pathways,126 cell survival,127 tight junction permeability,128-130 cytokine expression,131 and protein degradation.25,132

HSP70 is the most highly conserved member in the HSP family and has been studied in the response to acute exercise or exercise training in animals. Brief (5 min) eccentric exercise produces no increase in HSP70 protein expression in the muscle tissue,133 but longer and more exhaustive treadmill running134,135 or eccentric exercise136,137 results in a significant increase in HSP70 protein expression in cardiac and skeletal muscles. Elevated HSP70 levels are also observed in lung and kidney in response to strenuous endurance exercise.138

Findings on aerobic training on muscle HSP70 protein expression are conflicting. A high-intensity aerobic exercise protocol involving treadmill running (5 d) elevated HSP70 protein expression in both cardiac135 and skeletal muscle.139 Conversely, no increase in HSP70 was observed in animals exposed to either the continuous (low intensity and longer duration) or to the intermittent exercise protocol (high intensity and short duration).136,140

In conclusion, exercise (acute or training) raises the HSP70 levels but the magnitude of the response depends on the intensity141 and type of exercise.138

Exercise-induced HSP70 protein expression in humans

Our studies were among the first to show the effect of acute exercise on HSP70 protein expression in human peripheral white blood cells. Ryan et al. showed that treadmill exercise results in no apparent increase in HSP70 protein expression in human leukocytes.142 Similarly, 2 50-min bouts of moderate intensity aerobic exercise143,144 do not affect HSP70 levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). In our recent studies, strenuous treadmill running (rectal temperature of 40°C) produces a time-dependent increase in HSP70 protein expression in peripheral leukocytes, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.5 Similarly, a short (4 min) bout of “all-out” cycling results in a nonsignificant increase in HSP70 protein expression in monocytes and lymphocytes.145 On the contrary, running in a hot environment (40°C) with body temperature exceeding 39°C results in a significant increase in HSP70 in PBMCs within 1 h after exercise146 following an increase in HSP70 gene147 and transcript expression.148,149

Exhaustive endurance exercise has been consistently shown to trigger heat stress response in human leukocytes. In subjects who completed a half marathon (21.1 km) with an increased plasma creatine kinase activity indicating exercise-induced skeletal muscle damage and rectal temperature reaching 44°C, there is a post-exercise increase in HSP70 protein expression in monocytes and granulocytes that remains elevated for up to 1 d post-exercise.149,150 Similarly, exhaustive treadmill exercise,148,151 strenuous cycling,152,153 or repeated sprint cycle exercise154 augments HSP70 protein expression in leukocytes that lasts up to 48 h post exercise.

In skeletal muscle, moderate155 or high intensity exercise156 does not alter HSP70 protein expression within 3 h after cessation of exercise, despite the fact that HSP70 mRNA levels are upregulated 4 min post exercise156 and stay elevated 3 h after exercise termination.156,157 However, a significant effect of exercise on HSP70 protein expression in human skeletal muscle has been observed as early as 8 h post exercise158 and expression remains elevated up to 7 d after exercise termination.158-166

When examining exercise training effects on HSP70 protein expression in humans, it has been shown that a 7-d heat acclimation protocol consisting of 2 50-min exercise bouts in a warm environmental chamber elevates subjects’ core temperature to ≥ 39°C and results in a significant increase in HSP70 protein expression in peripheral leukocytes at 4-h post-exercise.144 Similarly, a 10-d acclimation program involving treadmill walking or running in a hot environment augments HSP70 content in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.143,167,168 Elevation of HSP70 in response to high-intensity and long-term training is also found after an 11-d training program, but not in response to short or moderate intensity exercise.146,169-172

Besides exercise intensity, training status and the type of exercise seem to exert considerable effect on HSP70 expression. In untrained subjects, 5-8 wk of triceps brachii training produce a significant increase in HSP70,173 whereas 12 wk of concentric contraction of biceps brachii decrease HSP70 protein expression in trained athletes.174 Taken together, exhaustive endurance (acute or training) exercise triggers a heat stress response in peripheral leukocytes as well as in skeletal muscles, but the magnitude of HSP70 expression depends on exercise intensity and training status.175 Future studies are needed to clearly determine the minimum amount of physical activity for increased heat stress response.

Exercise modulates autophagy in animals

Most scientific interest in autophagy and exercise has been observed in the last 4 y, despite the fact that the first study showing upregulated autophagy levels in response to exercise was published 3 decades ago.176 In these older studies, strenuous physical exercise associated with the appearance of necrotic fibers in skeletal muscle results in the most pronounced changes in autophagy levels between 2 and 7 d after exercise and returns to baseline within 2 wk after exertion. Recently these results were confirmed in mice performing a short but more strenuous exercise.177 Even low intensity aerobic exercise (10 m/min for 90 min), however, augments autophagy in the gastrocnemius muscle, and this effect is more pronounced in the fasted than in a fed state, suggesting that a decreased INS/insulin-AKT pathway in the fasted state exerts a less evident inhibitory effect on autophagy.178

It has also been shown that exercise-induced autophagy is not limited to skeletal muscle, and that it is also upregulated in adipose tissue, pancreatic β cells, and the brain.36,179

Deficiency of NR1D1/Rev-Erb-α (nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1), a nuclear receptor involved in controlling hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism results in dysfunctional mitochondria, their reduced biogenesis, and increased mitochondrial clearance via autophagy, as well as reduced exercise capacity. By contrast, pharmacological activation of NR1D1 with a synthetic ligand, SR9009, improves mitochondrial function and exercise endurance,180 suggesting that autophagy represents an important adaptive mechanism in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis under stress conditions.

The effect of exercise training on autophagy regulation seems to be multifactorial, and appropriate autophagy levels are fundamental for the well-being of an organism. Under basal conditions, the highest autophagy levels are observed in tonic, oxidative muscles (soleus). In plantaris muscle composed of both glycolytic and oxidative fibers, intermediate autophagy levels are observed; the lowest levels of autophagy proteins are present in glycolytic white vastus lateralis. Voluntary exercise training does not enhance already high basal autophagy levels in oxidative soleus muscle, but enhances basal autophagy flux in plantaris muscle.37 Besides skeletal muscle, aerobic training upregulates autophagy proteins (BECN1, ATG7, and LC3) in aortic and cardiac tissues.181,182 Moreover, it seems that autophagy also depends on the type of exercise. A 5-wk swimming program decreases gene expression of autophagy proteins (LC3), whereas 5 wk of wheel running increases Lc3 mRNA in the gastrocnemius.183

Autophagy is responsible for the removal of dysfunctional proteins, but uncontrolled and exceptionally upregulated autophagy may be harmful and lead to deleterious consequences. In rats, exposure to an effective antitumor agent, doxorubicin, results in cardiotoxicity that is associated with an increased oxidative stress and the upregulation of cellular proteolytic systems, including autophagy. Although aerobic training exerts no significant change on autophagic genes and proteins in control animals, it prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiac muscle damage and significantly reduces autophagy proteins.184 Similarly, transient middle cerebral artery occlusion leads to neurological dysfunctions and increases LC3 accumulation in the peri-infarct region. Physical exercise training improves neurological function and inhibits autophagosome accumulation in this region.185 In rats, pharmacologically induced diabetes results in increased muscle atrophy, reduction in diameter of the muscle fibers, and increased autophagy. Exercise training reverses these changes, increases muscle mass, and reduces autophagy levels.186 In mice with experimentally induced myopathy and increased autophagy proteins (LC3-II and SQSTM1/p62), 6 wk of exercise training prevents these changes leading to an improvement in muscle function and a decrease in atrophy.187

There is growing evidence suggesting that exercise, through the activation of previously suppressed autophagy, may provide beneficial effects. In dystrophic mice, voluntary exercise improves markers of oxidative capacity and autophagy levels, suggesting that exercise-induced autophagy levels account for exercise benefits.188 It has been reported that mutation in the Col6a−/−/collagen VI gene results in skeletal muscle myopathy that is characterized by myofiber degeneration and decrease in muscle strength.189 The Col6a−/− mutant mice fail to trigger autophagy in response to exercise and this appears to worsen the dystrophic condition in the mice.177 Long-term resistance training (9 wk) prevents age-related muscle atrophy and is associated with increased autophagy levels in rat gastrocnemius muscles.190 Similarly, regular aerobic exercise prevents an age-related decrease in autophagy proteins (BECN1 and ATG7), suggesting that exercise plays an important role in skeletal muscle remodeling through the modulation of the degradation of the crucial muscle proteins.191,192 Taken together, these studies demonstrate the requirement of autophagy in exercise-mediated development of skeletal muscle adaptation and physical endurance. They also suggest that exercise by controlling autophagy adjusts its intensity to the appropriate levels. Future studies are needed to show that autophagy contributes to the beneficial effect of exercise in disease prevention and life-span extension.

Exercise modulates autophagy in humans

Recently, studies have shown that 1 h of aerobic exercise (70–80% of VO2 max) in a warm (30°C) environment results in a significant increase in autophagy in peripheral leukocytes.5 Interestingly, glutamine supplementation resulting in an increase in HSP70 protein expression prevents this exercise-induced increase in autophagy, suggesting that autophagy remains under inhibitory control of the heat stress response. In human skeletal muscles, ultra-endurance running (149 km for more than 18 h) produces a significant increase in autophagy proteins (LC3-II and ATG12). These changes correlate with low plasma insulin levels, reduced activation of AKT, FOXO3, MTOR, and EIF4EBP1 (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1) and concurrent upregulation of AMPK.193 Conversely, a single bout of resistance exercise has no effect112 or reduced autophagy levels in both older and younger adults194 in skeletal muscle. Similar to resistance training, a short (20 min) sub-maximal aerobic exercise (cycle ergometer corresponding to 81% VO2 max) exerts no significant effect on autophagy regulation in human skeletal muscle.195 Finally, future research is needed to investigate the effect of exercise (intensity and type) on autophagy regulation in humans and to determine the role of autophagy under physical performance. A key question is to identify, besides exercise, optimal strategies including nutritional modifications that help autophagy work more effectively.

Autophagy and heat shock – cooperation through the complex stress of exercise

Model of control

The heat shock response was fully functional during the evolution of the system of autophagy. In addition, heat shock both manages denatured polypeptides and is essential for protein translocation, multimer assembly, refolding, and protein synthesis. Finally, cells must constantly switch between damaged protein clearance and rebuilding. These principles argue for a cooperative interaction between these 2 protein management systems, heat shock response and autophagy, where one exacts either activation or inhibitory control over the other. A recent study5 suggests that this is indeed the case and that the heat shock response regulates autophagy. Single gene overexpression of the HSP70 protein, the main executor of the heat shock response, inhibits starvation- or rapamycin-induced autophagy. In addition, under control conditions, HSF1, the central regulator of the heat shock response, negatively regulates autophagy.5 The molecular basis for modulation of autophagy by heat shock response includes activation of the AKT-MTOR pathway.

Additional evidence from blockage with other proteostasis pathways supports the above view. Pharmacologically induced proteasome inhibition upregulates autophagy in mouse cardiomyocytes,196 human prostate cancer cells,197 and human breast cancer cells.198 In mouse fibroblasts, autophagy is activated by selective blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy.199 Similarly, knockdown of an essential autophagy gene (ATG5) results in upregulation of chaperone-mediated autophagy in mouse embryonic fibroblasts.200 Inhibition of the proteasome by using MG132 activates autophagy in mouse embryonic fibroblasts through a downregulation of the AKT-TSC-MTOR pathway.201 Similarly, inhibition of the HSP70-dependent proteasomal pathway by methylene blue enhances degradation of androgen receptor through induction of autophagy, suggesting that the level of the heat shock response affects the activity of autophagy.202 Pretreatment with a chemical chaperone, 4-phenylbutyric acid, prevents an ER stress-induced decrease in the MTOR pathway and results in autophagy inhibition. In colorectal cancer cells, transient knockdown of HSP70 expression (siRNA) potentiates, whereas HSP70 overexpression (adenovirus to express HSP70) prevents, an increase in autophagy induced by the pro-apoptotic agent OSU-03012.203 Moreover, mild heat preconditioning associated with HSP70 overexpression inhibits heat-induced autophagy and this effect is diminished by HSP70 inhibition with triptolide pretreatment.84 The above studies indicate that the heat shock response and autophagy are linked and that autophagy remains under regulatory control of the heat shock response. In addition, we propose that HSP70 itself acts as a part of the intracellular control mechanism, switching the cell from the degradation phase to the building and protein synthesis phase.

Exercise as a model

The genesis of our hypothesis of heat shock regulatory control over autophagy was grounded in part upon the concept that cells must constantly switch between protein breakdown/clearance and rebuilding. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the complex stress of exercise. Consistent with cell-based studies of heat shock regulation of autophagy, it has been demonstrated that glutamine supplementation as a heat shock activator prior to exercise results in a significant increase in HSP70 protein expression in human PBMCs. This pre-exercise increase in HSP70 prevents the expected increase in autophagy in response to exercise in human subjects.5

The responses of skeletal muscle to exercise provide an example of physiological adaptations to constantly changing physical activity of an organism. At the cellular level, changes in intracellular temperature, pH, and energy status during exercise pose homeostatic challenges. In addition, the adaptation to work also poses significant challenges to the systems involved in breakdown, transport, and synthesis of proteins. In this regard, the skeletal muscle tissue is highly regulated by protein turnover comprised of degradation and rebuilding of the muscle fibers. In response to decreased mechanical stress, skeletal muscle tissue undergoes rapid atrophy characterized by the loss of mass and size.204,205 On the other hand, mechanical stimulation of the tissue leads to increased mitochondrial content,206 improved insulin sensitivity,207 enhanced muscle strength, and increased size.208 During catabolic conditions, muscle proteins are catabolized to maintain gluconeogenesis in the liver,209 but excessive degradation of the muscle tissue may be extremely damaging for the organism, leading to muscle wasting and even death. In patients with lung cancer cachexia, enhanced autophagy has been shown to increase muscle proteolysis, suggesting that impaired or exaggerated autophagy in the muscle tissue plays a role in the etiology of pathological conditions and is responsible for the damage of the muscle tissue.42,44

The immediate post-exercise phase is characterized by increases in catabolic signals such as IL6/interleukin 6 and protein turnover. In healthy, active human subjects, infusion of recombinant IL6 causes a significant increase in the net release of amino acids from the muscle.210 IL6, among other pro-inflammatory cytokines, has also been implicated in the development of a cachectic conditions in skeletal muscles211 and is also responsible for activation of autophagy in cell culture models.212

We propose that recovery from and adaptation to exercise represents a single, unified physiological response resulting from cooperation between autophagy and the heat shock response, 2 protein management systems. In this model, the initial phase of exercise-induced damage activates protein turnover to recycle and reclaim amino acids and to remove damaged proteins. This phase is mediated by a host of factors that drive autophagy. Turnover must be stopped to allow for repair. This protein synthesis and protein folding is regulated by heat shock proteins. When the cellular response to exercise is seen as a continuous process of coordinated breakdown and repair, this concept, coupled with the evidence that HSP70 may control autophagy,5 supports a model in which HSP control of autophagy is the mechanism by which the organism adapts to exercise. During this collaboration, autophagy and HSP function in concert in order to build muscle and create the adaptation. We propose that HSP serves as a switch that turns off autophagy and allows the organism to shift from reclamation to building.

The combined activities of autophagy and the heat shock response in exercise adaptation

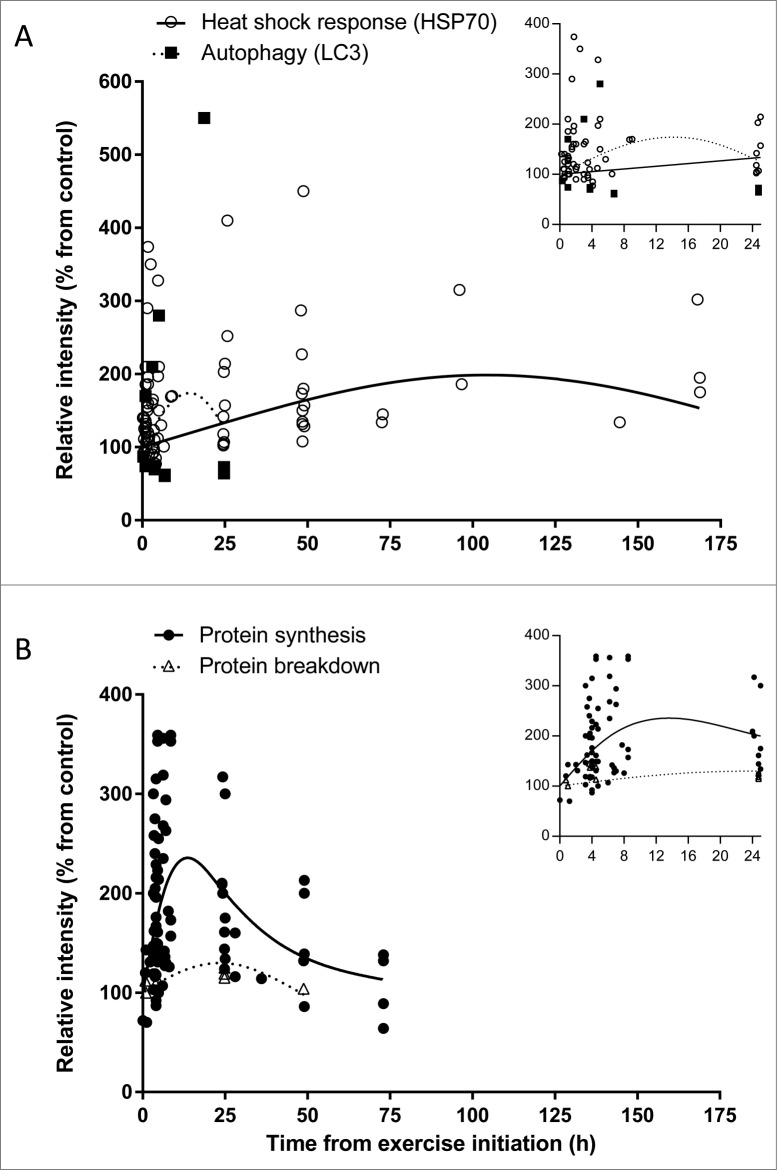

We undertook an analysis of the temporal relationship between the heat shock response, represented by changes in HSP70 protein expression, and autophagy, represented by changes in LC3 following exercise. We conducted a systematic search of PubMed focusing on the terms “exercise, autophagy, HSP70, protein synthesis, protein breakdown, and humans.” Four measures (autophagy, heat shock response, protein synthesis, and breakdown) have been included in the analysis presented in Figure 2 in support of this model. In our analysis, we collected and analyzed 1) 22 publications (with a total of 231 subjects) studying the effect of acute exercise on HSP70 protein expression in humans; 2) 5 publications (with a total of 70 subjects) examining the effect of acute exercise on autophagy activation; 3) 20 publications (with a total of 204 subjects) investigating the effect of acute exercise on protein synthesis in humans, and 4) 6 publications (with a total of 61 subjects) testing the effect of acute exercise on protein breakdown in humans. The following inclusionary and exclusionary criteria were used in our analysis: exercising human (both females and males) subject studies were used regardless of 1) age of participants , 2) training status of subjects, 3) exercise intensity (low, moderate, or high), 4) type of exercise (aerobic [running, cycling, or rowing] or resistance), 5) collected tissue (muscle tissue or white blood cells), 6) protein measurement (western blot analysis, flow cytometry, or immunostaining). Only studies with calculated relative protein intensity of LC3 (marker of autophagy) or HSP70 (marker of the heat stress response) were used in the analysis, followed by normalization to the control, pre-exercise, or baseline values and set to 100%. For resistance exercise, when duration of exercise was not provided, only time after exercise was used for the analysis, otherwise time from the initiation of the exercise was used. Due to exceptionally high (1000-3200 fold increase with standard error reaching ± 3000 compared with a combined average of 164 ± 1 in other studies) HSP70 protein expression, a study by Khassaf et al.160 was excluded from the analysis. We used linear and nonlinear regression analyses to describe relationships between time since initiation of exercise and HSP70 protein expression, autophagy, synthesis, and breakdown. Analyses accounted for random study effects, but did not weight study effect sizes by their precision, as variance estimates were not available for all studies. Prior to analyses, effect sizes on the percent scale were log-transformed (ln[Effect_ Size/100]) to improve normality of residual errors and homogeneity of variances. Models did not include an intercept, which constrained fitted models to predict 100% response at the initiation of exercise. Nonlinear regression with study random effects was used to analyze synthesis rate data. In addition we conducted exploratory analyses to assess whether trajectories differed with respect to whether measurements were made on skeletal muscle or on PBMCs.

Figure 2.

Time-course effect of acute exercise on (A) heat shock response (HSP70) and autophagy (LC3), and (B) protein synthesis and protein breakdown in humans based on acute exercise trials listed in Tables S1-4. Each dot represents 1 measurement. In both panels (A and B) the X-axis represents the time from the start of exercise, that is the sum of times in hours representing duration of exercise and collection time post-exercise; in panel (A), the Y-axis represents relative intensity of HSP70 protein expression (Table S1) or LC3 protein expression (Table S2); in panel (B), the Y-axis represents relative intensity of protein synthesis (Table S3) or protein breakdown (Table S4). (Insets) Expanded views of the first 25-h time point. Axes titles removed for clarity. The X-axis represents time from the start of exercise in hours, and the Y-axis represents relative intensity (% from control). In the (A) inset the Y-axis scale was truncated to improve clarity.

Time since initiation of exercise explained significant amounts of variation in HSP70 (P < 0.001), protein synthesis (P <0.001), and protein breakdown (P = 0.01), but not for autophagy (P > 0.15). As shown in Fig. 2, the analysis of human exercise studies demonstrates that autophagy represented by LC3 protein expression has only been measured ≤ 24 h after completion of exercise with 8 out of 12 points showing reduced expression shortly after exercise. Overall, a quadratic polynomial model shows a peak 1.75-fold increase in LC3 protein expression during the initial, degradation phase of exercise, about 14 h from the start of exercise. However, the relationship between time and autophagy appears to be different for PBMCs and muscle. Three points with increasing expression <8 h after exercise initiation were measured in PBMCs by Dokladny et al.,5 whereas 8 of 9 skeletal muscle observations had reduced expression. Given the limited number of autophagy measurements analyzed, additional studies are needed to assess autophagy measured in PBMCs and skeletal muscle. In contrast to the apparent initial increase and decline in autophagy within 24 h, cellular HSP70 levels rise to peak levels at about 105 h after exercise initiation (∼2-fold increase when compared with pre-exercise values) and then decline. These changes in autophagy and HSP70 levels correlate with changes in measures of protein breakdown and protein synthesis. In response to one bout of exercise, the rate of protein breakdown shows a modest change since exercise began increasing, to about 30% above baseline at about 24 h and then decreasing. Protein synthesis rate increased about 2-fold in the first 8 hours after initiation of exercise and gradually approached baseline after 24 h. Peak synthesis rate was predicted to be between 8 and 12 h; however, we found no studies with measurements in this range and therefore additional research is needed to determine the peak and duration of increased synthesis rate.

Conclusions

In the present review, we proposed a model of cooperation and control between autophagy and the heat shock response during exercise in humans. Our model has been supported by the direct cellular data of the effect of exercise on heat shock response and autophagy in humans. The model shows that autophagy is primarily upregulated in the initial degradation phase of exercise, whereas heat shock response is mainly activated in the building and protein synthesis phase of exercise. The model also suggests that heat shock response represented by HSP70 is an intracellular control mechanism switching the cell from the initial degradation phase (autophagy) to the building and protein synthesis phase. More studies are needed to fully determine the relationship between exercise and autophagy in exercising humans and animals and also to delineate the role of the heat shock response in regulation of other proteolytic systems in cell culture models, animals, and humans. As more research occurs and data accumulate, refinement of this model may help us understand the factors and conditions influencing the interactions between various intracellular systems responsible for maintaining protein homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vojo Deretic, Ph.D. and Matt Cotten, Ph.D. for their editorial comments.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 2011; 475:324-32; PMID:21776078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Low P. The role of ubiquitin-proteasome system in ageing. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2011; 172:39-43; PMID:21324320; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 2008; 451:1069-75; PMID:18305538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cuervo AM, Wong E. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: roles in disease and aging. Cell research 2014; 24:92-104; PMID:24281265; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cr.2013.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dokladny K, Zuhl MN, Mandell M, Bhattacharya D, Schneider S, Deretic V, Moseley PL. Regulatory coordination between two major intracellular homeostatic systems: heat shock response and autophagy. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:14959-72; PMID:23576438; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.462408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang J, Bridges K, Chen KY, Liu AY. Riluzole increases the amount of latent HSF1 for an amplified heat shock response and cytoprotection. PloS one 2008; 3:e2864; PMID:18682744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0002864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 2002; 295:1852-8; PMID:11884745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Phillips SM, Tipton KD, Aarsland A, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR. Mixed muscle protein synthesis and breakdown after resistance exercise in humans. Am J Physiol 1997; 273:E99-107; PMID:9252485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mosser DD, Martin LH. Induced thermotolerance to apoptosis in a human T lymphocyte cell line. J Cell Physiol 1992; 151:561-70; PMID:1295903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hotchkiss R, Nunnally I, Lindquist S, Taulien J, Perdrizet G, Karl I. Hyperthermia protects mice against the lethal effects of endotoxin. Am J Physiol 1993; 265:R1447-57; PMID:8285289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mailhos C, Howard MK, Latchman DS. Heat shock protects neuronal cells from programmed cell death by apoptosis. Neuroscience 1993; 55:621-7; PMID:8413925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Musch MW, Ciancio MJ, Sarge K, Chang EB. Induction of heat shock protein 70 protects intestinal epithelial IEC-18 cells from oxidant and thermal injury. Am J Physiol 1996; 270:C429-36; PMID:8779904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chu EK, Ribeiro SP, Slutsky AS. Heat stress increases survival rates in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated rats. Crit Care Med 1997; 25:1727-32; PMID:9377890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murata M, Gong P, Suzuki K, Koizumi S. Differential metal response and regulation of human heavy metal-inducible genes. J Cell Physiol 1999; 180:105-13; PMID:10362023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tyedmers J, Mogk A, Bukau B. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11:777-88; PMID:20944667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Polling S, Hill AF, Hatters DM. Polyglutamine aggregation in Huntington and related diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 769:125-40; PMID:23560308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moreno-Gonzalez I, Soto C. Misfolded protein aggregates: mechanisms, structures and potential for disease transmission. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2011; 22:482-7; PMID:21571086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mohamed A, Cortez L, de Chaves EP. Aggregation state and neurotoxic properties of alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2011; 12:235-57; PMID:21348837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lynch-Day MA, Mao K, Wang K, Zhao M, Klionsky DJ. The role of autophagy in Parkinson's disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2:a009357; PMID:22474616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem 1999; 68:1015-68; PMID:10872471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klionsky DJ, Codogno P. The mechanism and physiological function of macroautophagy. J Innate immun 2013; 5:427-33; PMID:23774579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. The N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1845-6; PMID:23656658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiang HL, Terlecky SR, Plant CP, Dice JF. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science 1989; 246:382-5; PMID:2799391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dice JF. Peptide sequences that target cytosolic proteins for lysosomal proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci 1990; 15:305-9; PMID:2204156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: a unique way to enter the lysosome world. Trends Cell Biol 2012; 22:407-17; PMID:22748206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mortimore GE, Lardeux BR, Adams CE. Regulation of microautophagy and basal protein turnover in rat liver. Effects of short-term starvation. J Biol Chem 1988; 263:2506-12; PMID:3257493 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2011; 27:107-32; PMID:21801009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 20:460-73; PMID:23725295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012; 11:709-30; PMID:22935804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Backues SK, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy gets in on the regulatory act. J Mol Cell Biol 2011; 3:76-7; PMID:20947614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 2010; 40:280-93; PMID:20965422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Activation of autophagy is required for muscle homeostasis during physical exercise. Autophagy 2011; 7:1405-6; PMID:22082869; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.7.12.18315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Masiero E, Agatea L, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Loro E, Komatsu M, Metzger D, Reggiani C, Schiaffino S, Sandri M. Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab 2009; 10:507-15; PMID:19945408; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raben N, Hill V, Shea L, Takikita S, Baum R, Mizushima N, Ralston E, Plotz P. Suppression of autophagy in skeletal muscle uncovers the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and their potential role in muscle damage in Pompe disease. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17:3897-908; PMID:18782848; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/ddn292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grumati P, Coletto L, Sabatelli P, Cescon M, Angelin A, Bertaggia E, Blaauw B, Urciuolo A, Tiepolo T, Merlini L, et al. Autophagy is defective in collagen VI muscular dystrophies, and its reactivation rescues myofiber degeneration. Nat Med 2010; 16:1313-20; PMID:21037586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, An Z, Loh J, Fisher J, Sun Q, et al. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature 2012; 481:511-5; PMID:22258505; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lira VA, Okutsu M, Zhang M, Greene NP, Laker RC, Breen DS, Hoehn KL, Yan Z. Autophagy is required for exercise training-induced skeletal muscle adaptation and improvement of physical performance. FASEB J 2013; 27:4184-93; PMID:23825228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1096/fj.13-228486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab 2007; 6:472-83; PMID:18054316; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, Masiero E, Rudolf R, Del Piccolo P, Burden SJ, Di Lisi R, Sandri C, Zhao J, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab 2007; 6:458-71; PMID:18054315; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dobrowolny G, Aucello M, Rizzuto E, Beccafico S, Mammucari C, Boncompagni S, Belia S, Wannenes F, Nicoletti C, Del Prete Z, et al. Skeletal muscle is a primary target of SOD1G93A-mediated toxicity. Cell Metab 2008; 8:425-36; PMID:19046573; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vergne I, Roberts E, Elmaoued RA, Tosch V, Delgado MA, Proikas-Cezanne T, Laporte J, Deretic V. Control of autophagy initiation by phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase Jumpy. EMBO J 2009; 28:2244-58; PMID:19590496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Penna F, Costamagna D, Pin F, Camperi A, Fanzani A, Chiarpotto EM, Cavallini G, Bonelli G, Baccino FM, Costelli P. Autophagic degradation contributes to muscle wasting in cancer cachexia. Am J Pathol 2013; 182:1367-78; PMID:23395093; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hosokawa S, Koseki H, Nagashima M, Maeyama Y, Yomogida K, Mehr C, Rutledge M, Greenfeld H, Kaneki M, Tompkins RG, et al. Title efficacy of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor on distant burn-induced muscle autophagy, microcirculation, and survival rate. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013; 304:E922-33; PMID:23512808; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00078.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Op den Kamp CM, Langen RC, Snepvangers FJ, de Theije CC, Schellekens JM, Laugs F, Dingemans AM, Schols AM. Nuclear transcription factor kappa B activation and protein turnover adaptations in skeletal muscle of patients with progressive stages of lung cancer cachexia. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 98:738-48; PMID:23902785; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3945/ajcn.113.058388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hussain SN, Sandri M. Role of autophagy in COPD skeletal muscle dysfunction. J Appl Physiol 2013; 114:1273-81; PMID:23085958; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/japplphysiol.00893.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007; 8:774-85; PMID:17712357; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hahn-Windgassen A, Nogueira V, Chen CC, Skeen JE, Sonenberg N, Hay N. Akt activates the mammalian target of rapamycin by regulating cellular ATP level and AMPK activity. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:32081-9; PMID:16027121; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M502876200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hardie DG, Scott JW, Pan DA, Hudson ER. Management of cellular energy by the AMP-activated protein kinase system. FEBS letters 2003; 546:113-20; PMID:12829246; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00560-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab 2005; 1:15-25; PMID:16054041; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Coffer PJ, Jin J, Woodgett JR. Protein kinase B (c-Akt): a multifunctional mediator of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Biochem J 1998; 335 ( Pt 1):1-13; PMID:9742206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Winder WW, Hardie DG. Inactivation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle during exercise. Am J Physiol 1996; 270:E299-304; PMID:8779952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fujii N, Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Smith JT, Habinowski SA, Kaijser L, Mu J, Ljungqvist O, Birnbaum MJ, Witters LA, et al. Exercise induces isoform-specific increase in 5'AMP-activated protein kinase activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 273:1150-5; PMID:10891387; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wojtaszewski JF, Nielsen P, Hansen BF, Richter EA, Kiens B. Isoform-specific and exercise intensity-dependent activation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 2000; 528 Pt 1:221-6; PMID:11018120; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00221.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sakamoto K, Aschenbach WG, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Akt signaling in skeletal muscle: regulation by exercise and passive stretch. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003; 285:E1081-8; PMID:12837666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sakamoto K, Hirshman MF, Aschenbach WG, Goodyear LJ. Contraction regulation of Akt in rat skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:11910-7; PMID:11809761; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112410200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Y, Gao X, Saucedo LJ, Ru B, Edgar BA, Pan D. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5:578-81; PMID:12771962; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4:658-65; PMID:12172554; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev 2003; 17:1829-34; PMID:12869586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1110003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Stocker H, Kozma SC, Hafen E, Bos JL, Thomas G. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell 2003; 11:1457-66; PMID:12820960; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00220-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bolster DR, Crozier SJ, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. AMP-activated protein kinase suppresses protein synthesis in rat skeletal muscle through down-regulated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:23977-80; PMID:11997383; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.C200171200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kimura N, Tokunaga C, Dalal S, Richardson C, Yoshino K, Hara K, Kemp BE, Witters LA, Mimura O, Yonezawa K. A possible linkage between AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling pathway. Genes Cells 2003; 8:65-79; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cheng SW, Fryer LG, Carling D, Shepherd PR. Thr2446 is a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) phosphorylation site regulated by nutrient status. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:15719-22; PMID:14970221; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.C300534200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13:132-41; PMID:21258367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mizushima N. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2010; 22:132-9; PMID:20056399; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science 2011; 331:456-61; PMID:21205641; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1196371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee JW, Park S, Takahashi Y, Wang HG. The association of AMPK with ULK1 regulates autophagy. PloS one 2010; 5:e15394; PMID:21072212; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0015394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shang L, Wang X. AMPK and mTOR coordinate the regulation of Ulk1 and mammalian autophagy initiation. Autophagy 2011; 7:924-6; PMID:21521945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.7.8.15860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Shang L, Chen S, Du F, Li S, Zhao L, Wang X. Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:4788-93; PMID:21383122; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1100844108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Roach PJ. AMPK ->ULK1 ->autophagy. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31:3082-4; PMID:21628530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.05565-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Greer EL, Oskoui PR, Banko MR, Maniar JM, Gygi MP, Gygi SP, Brunet A. The energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase directly regulates the mammalian FOXO3 transcription factor. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:30107-19; PMID:17711846; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M705325200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Cintra DE, Frederico MJ, de Pinho RA, Velloso LA, De Souza CT. Acute exercise modulates the Foxo1/PGC-1alpha pathway in the liver of diet-induced obesity rats. J Physiol 2009; 587:2069-76; PMID:19273580; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sanchez AM, Csibi A, Raibon A, Cornille K, Gay S, Bernardi H, Candau R. AMPK promotes skeletal muscle autophagy through activation of forkhead FoxO3a and interaction with Ulk1. J Cell Biochem 2012; 113:695-710; PMID:22006269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcb.23399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Richter EA, Hargreaves M. Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol Rev 2013; 93:993-1017; PMID:23899560; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00038.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ahlborg G, Felig P, Hagenfeldt L, Hendler R, Wahren J. Substrate turnover during prolonged exercise in man. Splanchnic and leg metabolism of glucose, free fatty acids, and amino acids. J Clin Invest 1974; 53:1080-90; PMID:4815076; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI107645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Newsholme P. Why is L-glutamine metabolism important to cells of the immune system in health, postinjury, surgery or infection? J Nutr 2001; 131:2515S-22S; discussion 23S-4S; PMID:11533304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Castell LM, Newsholme EA. The relation between glutamine and the immunodepression observed in exercise. Amino Acids 2001; 20:49-61; PMID:11310930; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s007260170065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Newsholme EA, Crabtree B, Ardawi MS. The role of high rates of glycolysis and glutamine utilization in rapidly dividing cells. Biosci Rep 1985; 5:393-400; PMID:3896338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF01116556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Newsholme P, Curi R, Pithon Curi TC, Murphy CJ, Garcia C, Pires de Melo M. Glutamine metabolism by lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils: its importance in health and disease. J Nutr Biochem 1999; 10:316-24; PMID:15539305; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0955-2863(99)00022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chakrabarti R. Transcriptional regulation of the rat glutamine synthetase gene by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Eur J Biochem 1998; 254:70-4; PMID:9652396; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:408-15; PMID:21478880; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gordon PB, Kovacs AL, Seglen PO. Temperature dependence of protein degradation, autophagic sequestration and mitochondrial sugar uptake in rat hepatocytes. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1987; 929:128-33; PMID:3593777; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhao Y, Gong S, Shunmei E, Zou J. Induction of macroautophagy by heat. Mol Biol Rep 2009; 36:2323-7; PMID:19152020; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11033-009-9451-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Han J, Xu X, Qin H, Liu A, Fan Z, Kang L, Fu J, Liu J, Ye Q. The molecular mechanism and potential role of heat shock-induced p53 protein accumulation. Mol Cell Biochem 2013; 378:161-9; PMID:23456460; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11010-013-1607-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hsu SF, Chao CM, Huang WT, Lin MT, Cheng BC. Attenuating heat-induced cellular autophagy, apoptosis and damage in H9c2 cardiomyocytes by pre-inducing HSP70 with heat shock preconditioning. Int J Hyperthermia 2013; 29:239-47; PMID:23590364; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/02656736.2013.777853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zhang M, Jiang M, Bi Y, Zhu H, Zhou Z, Sha J. Autophagy and apoptosis act as partners to induce germ cell death after heat stress in mice. PloS one 2012; 7:e41412; PMID:22848486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0041412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Nivon M, Richet E, Codogno P, Arrigo AP, Kretz-Remy C. Autophagy activation by NFkappaB is essential for cell survival after heat shock. Autophagy 2009; 5:766-83; PMID:19502777; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.8788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Li CW, Lin YF, Liu TT, Wang JY. Heme oxygenase-1 aggravates heat stress-induced neuronal injury and decreases autophagy in cerebellar Purkinje cells of rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013; 238:744-54; PMID:23788171; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1535370213493705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Oberley TD, Swanlund JM, Zhang HJ, Kregel KC. Aging results in increased autophagy of mitochondria and protein nitration in rat hepatocytes following heat stress. J Histochem Cytochem 2008; 56:615-27; PMID:18379016; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1369/jhc.2008.950873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kim JN, Lee HS, Ryu SH, Kim YS, Moon JS, Kim CD, Chang IY, Yoon SP. Heat shock proteins and autophagy in rats with cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Gut and liver 2011; 5:513-20; PMID:22195252; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.4.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Selimovic D, Porzig BB, El-Khattouti A, Badura HE, Ahmad M, Ghanjati F, Santourlidis S, Haikel Y, Hassan M. Bortezomib/proteasome inhibitor triggers both apoptosis and autophagy-dependent pathways in melanoma cells. Cell Signal 2013; 25:308-18; PMID:23079083; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Rao R, Balusu R, Fiskus W, Mudunuru U, Venkannagari S, Chauhan L, Smith JE, Hembruff SL, Ha K, Atadja P, et al. Combination of pan-histone deacetylase inhibitor and autophagy inhibitor exerts superior efficacy against triple-negative human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2012; 11:973-83; PMID:22367781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yang Y, Fiskus W, Yong B, Atadja P, Takahashi Y, Pandita TK, Wang HG, Bhalla KN. Acetylated hsp70 and KAP1-mediated Vps34 SUMOylation is required for autophagosome creation in autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:6841-6; PMID:23569248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1217692110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Desai S, Liu Z, Yao J, Patel N, Chen J, Wu Y, Ahn EE, Fodstad O, Tan M. Heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) controls chemoresistance and autophagy through transcriptional regulation of autophagy-related protein 7 (ATG7). J Biol Chem 2013; 288:9165-76; PMID:23386620; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112.422071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Funasaka T, Tsuka E, Wong RW. Regulation of autophagy by nucleoporin Tpr. Sci Rep 2012; 2:878; PMID:23170199; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep00878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pierce A, Podlutskaya N, Halloran JJ, Hussong SA, Lin PY, Burbank R, Hart MJ, Galvan V. Over-expression of heat shock factor 1 phenocopies the effect of chronic inhibition of TOR by rapamycin and is sufficient to ameliorate Alzheimer's-like deficits in mice modeling the disease. J Neurochem 2013; 124:880-93; PMID:23121022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/jnc.12080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nivon M, Abou-Samra M, Richet E, Guyot B, Arrigo AP, Kretz-Remy C. NF-kappaB regulates protein quality control after heat stress through modulation of the BAG3-HspB8 complex. J Cell Sci 2012; 125:1141-51; PMID:22302993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.091041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cuthbertson DJ, Babraj J, Smith K, Wilkes E, Fedele MJ, Esser K, Rennie M. Anabolic signaling and protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle after dynamic shortening or lengthening exercise. Am J Physiol EndocrinolMetab 2006; 290:E731-8; PMID:16263770; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00415.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Etheridge T, Atherton PJ, Wilkinson D, Selby A, Rankin D, Webborn N, Smith K, Watt PW. Effects of hypoxia on muscle protein synthesis and anabolic signaling at rest and in response to acute resistance exercise. Am J Physiol EndocrinolMetab 2011; 301:E697-702; PMID:21750270; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00276.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dreyer HC, Fujita S, Cadenas JG, Chinkes DL, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Resistance exercise increases AMPK activity and reduces 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 2006; 576:613-24; PMID:16873412; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Dreyer HC, Drummond MJ, Pennings B, Fujita S, Glynn EL, Chinkes DL, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Leucine-enriched essential amino acid and carbohydrate ingestion following resistance exercise enhances mTOR signaling and protein synthesis in human muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294:E392-400; PMID:18056791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00582.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Moore DR, Phillips SM, Babraj JA, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Myofibrillar and collagen protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle in young men after maximal shortening and lengthening contractions. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005; 288:E1153-9; PMID:15572656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00387.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Fry CS, Drummond MJ, Glynn EL, Dickinson JM, Gundermann DM, Timmerman KL, Walker DK, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Aging impairs contraction-induced human skeletal muscle mTORC1 signaling and protein synthesis. Skeletal muscle 2011; 1:11; PMID:21798089; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/2044-5040-1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Tang JE, Lysecki PJ, Manolakos JJ, MacDonald MJ, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Bolus arginine supplementation affects neither muscle blood flow nor muscle protein synthesis in young men at rest or after resistance exercise. J Nutr 2011; 141:195-200; PMID:21191143; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3945/jn.110.130138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chesley A, MacDougall JD, Tarnopolsky MA, Atkinson SA, Smith K. Changes in human muscle protein synthesis after resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol 1992; 73:1383-8; PMID:1280254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. MacDougall JD, Gibala MJ, Tarnopolsky MA, MacDonald JR, Interisano SA, Yarasheski KE. The time course for elevated muscle protein synthesis following heavy resistance exercise. Can J Appl Physiol 1995; 20:480-6; PMID:8563679; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/h95-038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Miller BF, Olesen JL, Hansen M, Dossing S, Crameri RM, Welling RJ, Langberg H, Flyvbjerg A, Kjaer M, Babraj JA, et al. Coordinated collagen and muscle protein synthesis in human patella tendon and quadriceps muscle after exercise. J Physiol 2005; 567:1021-33; PMID:16002437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]