Abstract

Background:

Studies of familial cancers have found that only a small subset of tissues are affected by inherited mutations in a given tumour suppressor gene (TSG) or proto-oncogene (POG), even though the mutation is present in all tissues. Previous tests have shown that tissue specificity is not due to the presence vs absence of gene expression, as TSGs and POGs are expressed in nearly every type of normal human tissue. Using published microarray expression data we tested the related hypothesis that tissue-specific expression of a TSG or POG is highest in tissue where it is of oncogenic importance.

Methods:

We tested this hypothesis by examining whether individual TSGs and POGs had higher expression in the normal (noncancerous) tissues where they are implicated in familial cancers relative to those tissues where they are not. We examined data for 15 TSGs and 8 POGs implicated in familial cancer across 12 human tissue types.

Results:

We found a significant difference between expression levels in susceptible vs nonsusceptible tissues. It was found that 9 (60%, P<0.001) of the TSGs and 5 (63%, P<0.001) of the POGs had their highest expression level in the tissue type susceptible to their oncogenic effect.

Conclusions:

This highly significant association supports the hypothesis that mutation of a specific TSG or POG is likely to be most oncogenic in the tissue where the gene has its highest level of expression. This suggests that high expression in normal tissues is a potential marker for linking cancer-related genes with their susceptible tissues.

Keywords: tumor suppressors, proto-oncogenes, familial cancer, Peto's paradox, gene expression

The tissue specificity of an inherited predisposition to cancer has been known of and speculated upon for a long time (Morgan, 1922; Little, 1923). It is a pattern seen in both tumour suppressor genes (TSGs) and proto-oncogenes (POGs). For example, inherited mutations in the TSG BRCA1 severely increase the risk of cancer in breast and ovarian tissues, but cause no added risk of cancer in many other tissue types (Welcsh and King, 2001). Similarly, inherited mutations in the KIT POG specifically increase the risk of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (Lindor et al, 2008).

Attempts to explain these phenomena have largely focussed on TSGs (Bignold, 2004), with the usual assumption being that a given TSG acts as a critical cancer suppressor in the predisposed tissues, but not in those tissues with no elevated risk of hereditary cancer (Weinberg, 1988; Horowitz et al, 1990). For example, Weinberg (1988; Horowitz et al, 1990) proposed that RB1 had been recruited by evolutionary processes for the regulation of cell division in retinal and bone tissues, given that RB1 germline mutations were associated with high lifetime risks of retinoblastoma (Knudson, 1971) and osteosarcoma (Stratton et al, 1989).

This explanation of tissue specificity was formalised into an evolutionary model of cancer suppression by Nunney (1999). The model is based on multistage carcinogenesis and quantifies how cancer risk increases with a larger body size (more cells) and a longer lifespan (more cell divisions) (a relationship strongly supported by data from humans and dogs; Nunney, 2013), and how increased pre-reproductive risk drives natural selection for tissue-specific increases in cancer suppression. This recognition that cancer suppression is an evolving trait resolves the paradox first noted by Peto (1977): why don't large long-lived humans have much higher rates of cancer than small short-lived mice? This suppression is predicted to involve either tissue-specific mechanisms that directly reduce the risk of the target cancer (e.g., a TSG upregulated in a single tissue) or more general mechanisms affecting all tissues that would also lower the risk of all cancers. Examples of general mechanisms (global telomerase suppression, and early contact inhibition) have already been identified in large and long-lived rodents (Seluanov et al, 2007, 2009). Tissue-specific mechanisms are harder to detect, but the serendipitous availability of tissue-specific mutations would predict that different TSGs may be recruited independently over time in different tissues within a species, and that different TSGs may be recruited in the same tissue in different species clades.

One potential consequence of this evolutionary process would be that TSGs are only expressed in tissues where they actively suppress carcinogenesis. However, most TSGs and POGs are expressed in every type of normal human tissue. This was first investigated using RB1 that was found to be expressed in every tissue tested (Friend et al, 1986; Fung et al, 1987; Lee et al, 1988). Studies of other genes have found the same pattern in gene expression (Fearon, 1997; Vogelstein and Kinzler, 2004) and protein data (Plevová et al, 2005).

The ubiquitous expression of TSGs and POGs has thus been recognised as an enigma of cancer research (Knudson, 1989; Weinberg, 1989, 2007; Eng and Ponder, 1993; Brown and Solomon, 1997; Fearon, 1997; Bignold, 2004; Vogelstein and Kinzler; 2004), prompting alternative explanations that do not predict differences in expression across tissue types (see Bignold, 2004; Friedenson, 2010). For example, it has been proposed that the specificity of BRCA1 to breast and ovarian cancers might result from BRCA1 mutations being less likely to induce apoptosis in breast and ovarian tissues than in other tissues (Elledge and Amon, 2002, see also Monteiro, 2003). However, such ad hoc hypotheses lack generality because they fail to explain why such tissue specificity is the rule rather than the exception.

Recent work on TSGs suggests that their level of expression, rather than presence or absence, may be an important indicator of the cancer suppressing activity. The TSGs have multiple functions affecting tissues generally, in addition to their roles in cancer suppression (Venkitaraman, 2002; Silver and Livingston, 2012); however, a higher tissue-specific level of expression may indicate a role in suppressing cancer in the target tissue. Berger et al (2011) recently argued that higher levels of TSG expression correspond to lower cancer risk. For example, mice with slightly reduced expression levels (80%) of the TSG Pten have intermediate mammary tumour incidence compared with Pten+/+ (100%) and Pten+/− (50%) mice (Alimonti et al, 2010). In humans, haploinsufficiency of the TSGs PTEN (Marsh et al, 1998) and TP53 (Varley et al, 1997) has been linked to cancer, and this runs counter to the expectation that a single copy of a TSG is sufficient to suppress cancer. In such cases, loss-of-heterozygosity events of the remaining wild-type allele were not found. This suggests that, at least in some cases, a 50% reduction in expression substantially reduces the protective effect of a TSG.

Overall, these findings suggest that TSGs may be expressed at constitutively higher levels in the tissues where they are recruited to suppress cancer relative to those in which they are not. This hypothesis has been tested by two studies to date; however, support was weak or absent. Plevová et al (2005) examined the protein expression levels of the DNA mismatch repair tumour suppressors, MLH1 and MSH2, commonly associated with colorectal and uterine cancers. They found that both proteins had significantly higher expression in the susceptible tissues, but only if nonsusceptible testes tissue that showed the highest expression level for both proteins was excluded. Lage et al (2008) used microarray data from noncancerous samples of 73 tissues to examine the relative expression of 51 genes linked to hereditary cancer and did not find the predicted pattern in POGs or TSGs.

The two-hit role of TSGs in cancer suppression is well established; however, it is also possible for POGs to be recruited to provide one-hit protection (Nunney, 1999). The role of POGs in transmitting growth signals (Bunz, 2008) appears to make them less likely candidates for cancer suppression, as it requires that each added POG defines a new necessary signal for tissue growth. However, POGs are implicated in some familial cancers (the first was RET; Mulligan et al, 1993) and their possible role in the evolution of cancer suppression needs to be investigated. To this end, we were interested in testing the same hypothesis in POGs that has been proposed for TSGs: that a POG has higher expression in the susceptible tissue type(s) assuming that a susceptible tissue is where the POG provides a required signal for tissue growth.

The goal of this study was to test the prediction that TSGs and POGs implicated in familial cancer in a specific tissue are expected to have a high level of expression in that tissue. Using 15 TSGs and 8 POGs implicated in various tissue-specific familial cancers, we tested for higher expression in the affected tissue across 12 tissue types (plus some additional subtypes) using published mRNA expression data from normal (noncancerous) tissues.

Materials and Methods

Gene expression data set

We used data from 35 independently published microarray data sets documenting gene expression for a range of human tissues (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1) using the HG-U133A Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA) platform. These data were compiled and normalised by Zheng-Bradley et al (2010), and the data set is publicly available online at ArrayExpress (Accession no. E-MATB-27). The multistudy data set was downloaded using the Bioconductor software (Gentleman et al, 2004) in R (R Development Core Team, 2008). All probe sets were retained in our subset. Most cancer-related genes were covered by a single probe set. In those cases where two probe sets were present (RB1 and PTCH1), these were included as replicate measures of expression.

Table 1. The 12 broad tissue categories and the 38 subtissue types contained in the analysed multistudy data set that was compiled from 35 independent studies.

| Tissue category | Sample size | Original data source |

|---|---|---|

| Adipocyte | 14 | 1, 2 |

| Adipose tissue normal | 8 | |

| Adipose-derived adult stem cells | 6 | |

| Bone | 7 | 3 |

| Bone | 7 | |

| Brain+nerve | 150 | 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| Amygdala | 1 | |

| Brain | 39 | |

| Caudate nucleus | 30 | |

| Cerebellum | 26 | |

| Frontal cortex | 27 | |

| Hippocampus CA1 | 5 | |

| Hypothalamus | 20 | |

| Prefrontal cortex | 2 | |

| Endocrine organs | 7 | 7, 10 |

| Thyrocyte | 6 | |

| Thyroid gland | 1 | |

| Epithelium | 33 | 11 |

| Bronchial epithelium | 33 | |

| Gastrointestinal organs | 13 | 12, 13 |

| Oesophagus epithelium | 7 | |

| Small intestines | 6 | |

| Head+neck | 33 | 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 |

| Conjuctiva | 4 | |

| Hypopharynx | 3 | |

| Oropharynx | 1 | |

| T cell | 9 | |

| Tonsil | 10 | |

| Trabecular meshwork cell | 6 | |

| Heart+muscle | 74 | 19, 20, 21, 22,23, 24, 25, 26 |

| Heart | 36 | |

| Myometrium | 12 | |

| Skeletal muscle | 17 | |

| Smooth muscle | 9 | |

| Immune system | 25 | 15, 27, 28 |

| CD34+ blood cell thymus | 1 | |

| Lymph node | 10 | |

| Thymocyte | 14 | |

| Female reproductive | 34 | 26, 29, 30, 31 |

| Ovary | 4 | |

| Placenta basal plate | 21 | |

| Smooth muscle | 1 | |

| Theca | 8 | |

| Male reproductive | 12 | 32, 33 |

| Prostate gland | 11 | |

| Testis | 1 | |

| Skin | 25 | 26, 34, 35 |

| Endothelial cells | 8 | |

| Epidermis | 5 | |

| Keratinocyte | 8 | |

| Skin | 4 | |

| Total | 427 |

The total number of biological samples being tested for each broad tissue category and its corresponding subtissues is shown. Each of the 35 independent studies are listed in numerical code next to the tissue categories for which they contributed data. See Supplementary Table S1 for the complete reference corresponding to each code number. For additional details, see Zheng-Bradley et al (2010).

In our analysis we used all of the broad tissue categories used to group the biological samples in the data set except for cell line and liver, because cell line samples may not accurately reflect expression at the tissue level in vivo, and the liver tissue category contained only a single sample. We also removed tissues annotated as ‘disease' or ‘neoplasia' as only normal tissue was being analysed. The final 12 tissue categories used in the analysis and their corresponding sample sizes are represented in Table 1.

Criteria for selecting genes

Our initial screen required that a TSG or POG could be included in the analysis only if it was implicated in cancer via both germline and somatic mutations (using Supplementary Table S1 in Futreal et al, 2004). Both types of mutational effect were included in the screen in order to select only those TSGs and POGs likely to increase susceptibility across a range of developmental conditions in which the genes are mutated. For example, if a gene had a germline effect, but no known somatic effect, then this could indicate that the oncogenic activity of the mutant gene was restricted to very early development, a possibility our analysis of adult tissue could not detect.

In our second screen, we identified tissues significantly at risk from germline mutation using the criterion that lifetime cancer risk (by age 70 years) for individuals carrying a mutation in the target gene had to be ≥25% using median values from Lindor et al (2008). When relative risk (RR) scores were reported, the RR was converted using baseline risk data (x) from Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) (Ries et al, 2008), that is, (x)(RR) ≥25. For some genes, the 25% criterion excluded all tissue types. For these genes alone, a single tissue type that most exceeded a lower threshold of 15% lifetime risk was retained.

In applying this second screen it was found that of the POGs identified in the first screen, only RET (multiple endocrine neoplasia type II), HRAS, and KIT were included in Lindor et al (2008). RET passed the second screen. However, as the absence of the other POGs was probably because of their relatively recent discovery as hereditary cancer genes, we used other sources to assess risk. Each one of these genes was associated with only one major cancer type, as reported in the Cancer Gene Census (Futreal et al, 2004; Supplementary Table S1), and all of these cancer types were found to be above the 25% lifetime risk threshold using data from OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; see Hamosh et al, 2005).

Cancers affecting a tissue not represented in the 12 tissue types were not considered (e.g., colorectal cancer). Also excluded were (1) cancer types with diverse tissues of origin such as harmartomas and desmoid tumours, and (2) cancer types with unknown tissues of origin, such as rhabdoid tumours.

Statistical tests

All statistical tests were performed in the statistical program R (R Development Core Team, 2008), with the exception of the nested ANOVA model for which Minitab 16 (Minitab Inc., Pennsylvania, PA, USA) was used. The normality and equal variance assumptions of the log2(expression) data for each gene were tested using the Jarque–Bera test and the Bartlett test. As the data for several genes were found to be nonnormal, in most cases nonparametric statistical tests were performed.

Tissue and subtissue categories

All statistical testing for higher expression in susceptible tissues relative to nonsusceptible tissues were performed initially using the 12 broad tissue categories with (usually) one tissue identified as ‘susceptible' for each gene and the remainder grouped as ‘nonsusceptible'. For some genes it was possible to use subtissue data (given an adequate sample size >2; see Table 1) to refine the initial analysis by identifying the susceptible subtissue within the susceptible tissue using OMIM (Hamosh et al, 2005), so that the remaining subtissue samples of that tissue type could be grouped as ‘nonsusceptible subtissues', creating a 13th category.

Comparing gene expression in susceptible vs nonsusceptible tissue groups

The grand mean expression values of each gene in its susceptible vs nonsusceptible tissues/subtissues were compared using the one-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test applied separately to TSGs and POGs. The one-tailed test was performed, given the directional alternate hypothesis of higher expression in susceptible tissue. For each gene, the grand means were calculated as the unweighted average of the means of the relevant tissue/subtissue groups.

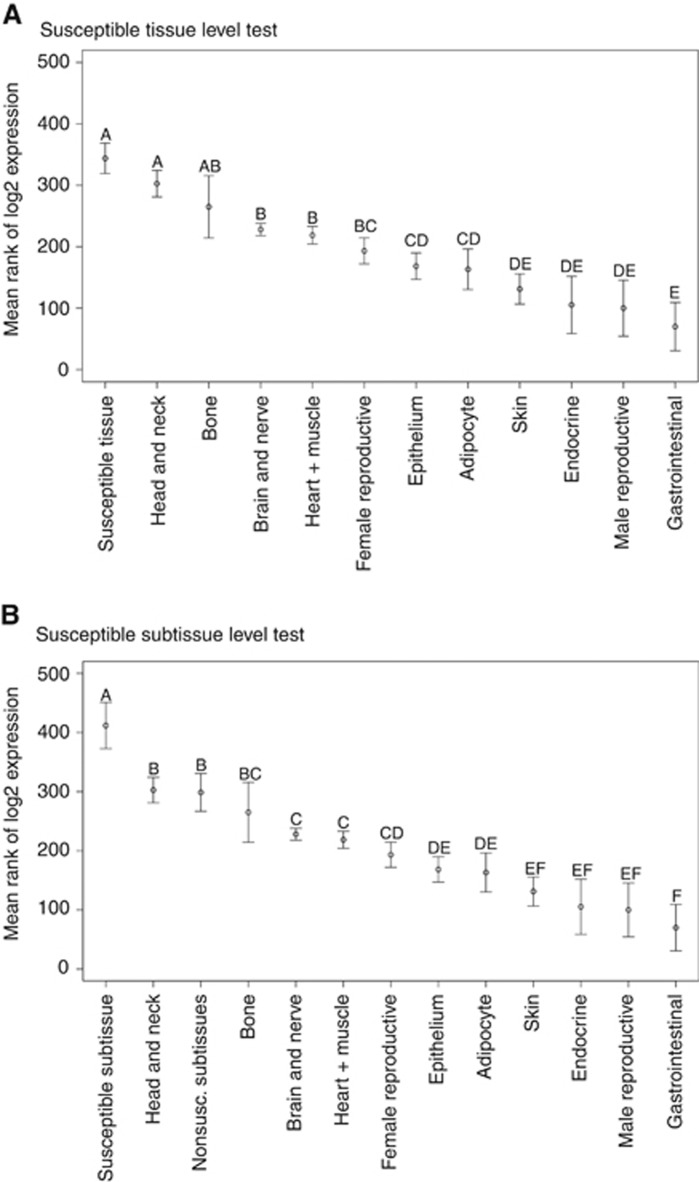

In a second analysis, each gene was tested individually. First, for each gene, we tested for significant differences in expression levels among the tissue/subtissue groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test. If significant expression-level differences between tissues were established (P<0.05 after Bonferroni correction for testing multiple genes), the Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparison test was performed across the tissue types. In this a posteriori test, which controlled the family-wise error rate at 0.05, the tissue means were ranked and grouped by significance, with the ‘A' group corresponding to the highest expression level. Tissues could be assigned to more than one group, for example, expression in a tissue classified as ‘AB' would only be significantly higher than tissues not in groups ‘A' or ‘B'. Only those tissue types marked as ‘A' alone (i.e., not ‘AB' etc.) were considered most highly expressed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparison test are diagrammed for the ATM tumour suppressor gene for its initial test based on (A) tissue category and (B) the final test using the susceptible subtissue. The figure shows the significance categories (A, AB, and so on) separating the samples. In the subtissue test, the susceptible tissue category (Immune System) was divided into a susceptible subtissue (lymph node) and a nonsusceptible subtissue (two subtissues) grouping (see Table 1).

The number of ‘A' classifications assigned to the susceptible tissue/subtissue of TSGs or POGs relative to the total number of ‘A' classifications was used to determine whether there was a nonrandom association. The statistical significance of the relationship was determined by simulated resampling of the data to determine the distribution of the number of ‘A's expected to be assigned to the susceptible group under the null hypothesis. A total of 10 000 trials were run and each trial involved cycling through each of the TSGs (or POGs) in turn and taking a random sample of size 1 or 2 (corresponding to the number of susceptible tissues for that gene) from the observed distribution of letter groupings for that gene. The number of ‘A's chosen across all TSGs (or POGs) was the score for that trial. The statistical significance of the observed score was evaluated based on its position relative to the null distribution.

Tests of lab effect

We examined the effect of using data from different laboratories, as these effects are known to be strong (Zilliox and Irizarry, 2007). Most labs tested only one tissue type, and hence to avoid subtissue variation we only compared labs that used the same subtissue type to represent that tissue. The resulting data set was analysed using a nested ANOVA model (Model: Expression=Subtissue+Gene+Lab(Subtissue)+Gene × Subtissue+Gene × Lab(Subtissue)), with Gene and Subtissue as fixed effects, and Lab as a random effect. Of interest is the Gene × Lab(Subtissue) interaction where the null expectation is that the ordering of expression across genes is constant for a given subtissue. We also calculated the (Pearson) correlation for gene expression levels both within and between labs. Within labs the multiple correlation coefficients were averaged using the Fisher's z-transform (z=(1/2)ln[(1+r)/(1−r)]), and between labs the correlation was based on the average expression levels of each lab.

Results

We identified 36 genes that had both hereditary and somatic mutations linked to cancer, of which 28 were represented by the probe sets within the expression array. Of these 36 genes, 23 (15 TSGs and 8 POGs) satisfied our criteria for a high-risk familial effect, with each affecting a single susceptible tissue, with the exception of PRKAR1A, a TSG that defined two susceptible tissues (Table 2). Within this group, it was possible to identify susceptible vs nonsusceptible subtissues within the susceptible tissue category in 11 TSGs and 2 POGs (Table 2).

Table 2. The susceptible tissue/subtissue and cancer type associated with the TSGs and POGs identified for analysis, plus the expression of these genes in susceptible vs nonsusceptible tissues.

| Gene type | Gene | High-penetrance cancer | Susceptible tissue type | Kruskal–Wallis test P-value | Expression (susc. tissue) | Expression (other tissues) | Significance category | Relative expression | Susceptible subtissue | Rel. expr. in susc. subtissue | Subtissue significance category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour suppressor genes | ATM | Leukaemia, lymphoma | Immune system | 5.06E−15 | 2.886±0.472 | −0.028±0.206 | A (2) | 7.54 | Lymph node | 11.68 | A (1) |

| STK11 | gastrointestinal polyps | Gastrointestinal | 5.06E−15 | 1.814±0.173 | 0.108±0.224 | A (2) | 3.26 | Small intestine | 3.34 | A (3) | |

| NF1 | Glioma, other CNS cancers | Brain and nerve | 5.06E−15 | 0.645±0.076 | −0.432±0.205 | A (1) | 2.11 | NA | |||

| RB1 | Osteosarcoma | Bone | 5.06E−15 | 0.62±0.203 | −0.060±0.123 | A (2) | 1.60 | NA | |||

| SMAD4 | Gastrointestinal polyps | Gastrointestinal | 1.29E−03 | 0.878±0.324 | 0.260±0.106 | A (2) | 1.53 | Small intestine | 2.21 | A (1) | |

| CDKN2A | Melanoma | Skin | 2.99E−07 | 0.904±0.510 | 0.386±0.389 | B | 1.43 | Epidermis | 0.41 | E | |

| MEN1 | Parathyroid adenoma | Endocrine | 5.06E−15 | −0.246±0.139 | −0.758±0.249 | B | 1.43 | Thyrocyte | 1.26 | A (7) | |

| BRCA2 | Prostate | Male reproductive | 1.17E−10 | 0.106±0.190 | −0.237±0.194 | BC | 1.27 | Prostate gland | 1.01 | A (6) | |

| PRKAR1A | Myxoma | Heart and muscle | 5.06E−15 | 0.655±0.099 | 0.015±0.331 | BC | 1.56 | Heart | 2.36 | A (2) | |

| PHOX2B | Neuroblastoma | Brain and nerve | 2.02E−12 | −0.066±0.067 | 0.134±0.203 | BC | 0.87 | NA | |||

| PTCH1 | Skin basal cell | Skin | 5.06E−15 | −0.069±0.116 | 0.136±0.156 | BC | 0.69 | Keratinocyte | 0.86 | BC | |

| MLH1 | Endometrial | Female reproductive | 5.06E−15 | −0.211±0.088 | −0.387±0.190 | CD | 1.13 | Placenta basal plate | 1.19 | CD | |

| BRCA1 | Ovarian | Female reproductive | 5.06E−15 | −0.779±0.070 | −0.394±0.173 | CDE | 0.77 | Ovary | 0.77 | DE | |

| TP53 | Osteosarcoma | Bone | 5.06E−15 | −0.378±0.045 | −0.222±0.172 | D | 0.90 | NA | |||

| MSH2 | Ovarian | Female reproductive | 5.06E−15 | −0.807±0.081 | −0.487±0.157 | DE | 0.80 | Ovary | 1.67 | A (3) | |

| PRKAR1A | Testicular | Male reproductive | 5.06E−15 | −0.198±0.260 | 0.093±0.335 | EF | 0.82 | NA | |||

| TSG average: | 0.368±0.254 | −0.130±0.082 | |||||||||

| Proto-oncogenes | RET | Medullary thyroid | Endocrine | 1.40E−11 | 7.097±2.437 | 0.158±0.164 | A (3) | 122.77 | NA | ||

| TSHR | Thyroid adenoma | Endocrine | 7.13E−03 | 6.588±4.292 | 0.868±0.399 | A (1) | 52.72 | NA | |||

| MPL | Myeloproliferative disorder | Bone | 1.08E−12 | 2.594±0.598 | 0.519±0.211 | A (1) | 4.21 | NA | |||

| ALK | Neuroblastoma | Brain and nerve | 5.06E−15 | 0.697±0.065 | −0.261±0.108 | A (1) | 1.94 | NA | |||

| EGFR | Non-small-cell lung cancer | Epithelium | 5.06E−15 | 0.473±0.056 | 0.112±0.186 | A (5) | 1.28 | NA | |||

| LMO1 | Neuroblastoma | Brain and nerve | 7.59E−07 | 0.179±0.076 | 0.106±0.140 | ABCD | 1.05 | NA | |||

| KIT | Gastrointestinal stromal tumour | Gastrointestinal | 5.06E−15 | 1.053±0.255 | 1.062±0.138 | CD | 0.99 | Small intestine | 0.79 | CD | |

| HRAS | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Heart and muscle | 5.06E−15 | −0.743±0.089 | −0.76±0.329 | DE | 1.01 | Skeletal muscle | 1.6 | C | |

| POG average: | 2.24±1.06 | 0.225±0.209 |

Abbreviations: CNS= central nervous system; NA=not applicable; POG=proto-oncogene; Rel. expr.=relative expression; susc.=susceptible; TSG=tumour suppressor gene.

For each gene, results are shown for the Kruskal–Wallis test across the 12 broad tissue categories (P-value=significance after Bonferroni correction) and the significance categories assigned to the susceptible tissue in the subsequent Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparison test. For genes in significance category ‘A', the total number of tissues tied in that category is given in parentheses. Also shown are the log2 expression (±1 s.e.) of each gene in the susceptible tissue type, the mean for the 11 other tissues and the ratio of these expression levels. For those genes that could also be analysed at the level of subtissue, the results from the subtissue analysis are also shown.

Analysis of the average expression of the 15 TSGs and 8 POGs showed that both groups had significantly higher expression in susceptible tissue categories, where mutations result in familial cancer, relative to nonsusceptible tissue categories. The mean log2 expression levels (±1 s.e.) of TSGs in susceptible and nonsusceptible tissue were 0.368±0.254 and −0.130±0.082, respectively, and in POGs they were 2.24±1.06 and 0.225±0.209, respectively (Table 2) (Wilcoxon signed rank test: TSGs, V=89, P=0.05, d.f.=14; POGs, V=35, P=0.008, d.f.=7). This reflected the finding that 10 of 15 TSGs and 7 of 8 POGs had a higher expression level in the susceptible tissue categories relative to the mean of the nonsusceptible tissue categories (Table 2). The same trend was also found when the susceptible tissue was more narrowly defined as a subtissue (Wilcoxon signed rank test: TSGs, V=91, P=0.04, d.f.=14; POGs, V=33, P=0.02, d.f.=7), again with 10 of 15 TSGs and 7 of 8 POGs having a higher expression level in the susceptible subtissue relative to the mean of the nonsusceptible tissues (Table 2).

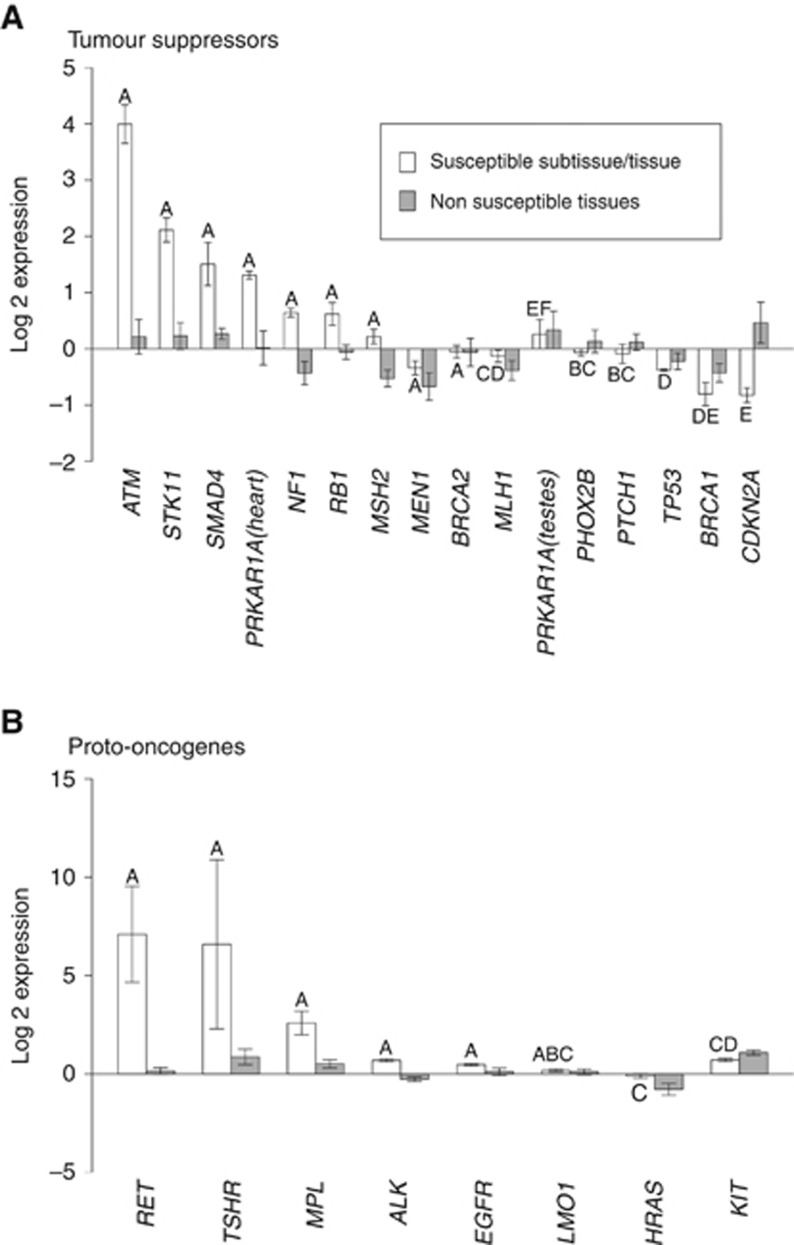

We next examined the more stringent hypothesis that in its susceptible tissue or subtissue the expression level of a TSG or POG is in the statistically most highly expressed tissue (or group of tissues) for that gene. We first established that there was highly significant differences in expression among tissues for all 23 genes (Kruskal–Wallis test; P<0.01 in all cases, after Bonferroni correction; see Table 2). A posteriori testing to assign a significance category to each susceptible tissue showed that 33% (5 out of 15) of TSGs and 63% (5 out of 8) of POGs were most highly expressed in their susceptible tissue (Table 2). Data resampling tests identified these patterns to be significant for both TSGs (P=0.02) and POGs (P=0.0003). The pattern for TSGs became much stronger when we refined the analysis using, where possible, expression data from susceptible subtissue rather than from the broad tissue category. Of the 11 TSGs where a susceptible subtissue was identified, 4 out of the 8 that were not characterised by significance category ‘A' in the initial tissue-level analysis moved into significance category ‘A' in the subtissue analysis. The 3 TSGs significant at the tissue category level remained so in the subtissue analysis (Table 2), so that 9 out of 15 TSGs (60% P=0.0001) had their significantly highest expression in their susceptible tissue (Figure 2A). There was no difference in the number of ‘A's between the subtissue and the broad tissue category score for POGs (Table 2), and hence their significance was unchanged (P=0.0003). The overall pattern in POGs is shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

Expression levels (±1 s.e.) in susceptible tissues relative to nonsusceptible tissues for (A) TSGs and (B) POGs. The ‘Susceptible Subtissue/Tissue' bars show the mean of log expression for the susceptible subtissue (where possible) or of the susceptible tissue. The ‘Nonsusceptible Tissue' bars show the average of the mean values for the nonsusceptible tissues. The letters above each ‘Susceptible Subtissue/Tissue' bar show its relevant significance category. The abbreviation for each gene is given on the x axis.

We examined whether using data from different laboratories added significant variation within our tissue groupings using the cases where it was possible to test for heterogeneity in the ranking of the expression values of all genes within the same subtissue. There were six types of subtissue that were used in more than one lab, with two or three labs per subtissue (Table 3). With lab nested within subtissue, ANOVA revealed a highly significant Gene by Lab (Subtissue) interaction (P<0.001; Table 3), indicating that, for at least some genes, the ranking of the expression levels across subtissues varied among labs. This laboratory effect would lessen the chance of the data revealing a consistent pattern.

Table 3. Variation in gene expression levels within and between laboratories testing the same subtissue.

| Tissue category | Subtissue | Lab ID | Sample size | Within-lab correlation (r) | Between-lab correlation (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain+nerve | Caudate nucleus | E-AFMX-6 | 29 | 0.715 | 0.732 |

| GSE3790 | 1 | NA | |||

| Heart+muscle | Heart | GSE2240 | 23 | 0.722 | 0.880 |

| GSE974 | 13 | 0.606 | |||

| Heart+muscle | Smooth muscle | E-MEXP-569 | 8 | 0.749 | 0.570 |

| E-MEXP-66 | 1 | NA | |||

| Endocrine organs | Thymocyte | E-MEXP-337 | 13 | 0.623 | 0.853 |

| GSE1460 | 1 | NA | |||

| Brain+nerve | Brain | GSE5392 | 23 | 0.582 | 0.662 |

| E-LGCL-5 | 15 | 0.679 | 0.301 | ||

| E-TABM-145 | 1 | NA | 0.598 | ||

| Heart+muscle | Skeletal muscle | GSE3307 | 9 | 0.797 | 0.822 |

| GSE6011 | 7 | 0.803 | 0.793 | ||

| GSE1786 | 1 | NA | 0.449 |

|

Expression=subtissue+gene+lab(subtissue)+subtissue × gene+lab(subtissue) × gene | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | d.f. | SS | F-value | P-value |

| Subtissue | 5 | 155.5 | 6.97 | 0.003 |

| Gene | 22 | 1003.7 | 11.86 | <0.001 |

| Lab(subtissue) | 8 | 22.8 | 1.1 | 0.362 |

| Subtissue × gene | 110 | 2510.6 | 6.14 | <0.001 |

| Lab(subtissue) × gene | 176 | 554.2 | 4.18 | <0.001 |

| Error | 3303 | 2489.0 | ||

The subtissues and their corresponding laboratories (represented by an ArrayExpress experiment ID) are given along with the number of tissue samples that were tested in each lab. For each lab (with sample size >1) an average within-lab correlation was calculated using the expression values across all 23 genes in each sample. For each subtissue, the pairwise correlation between all labs is given (in the order lab 1 vs 2, 1 vs 3, and 2 vs 3) using the mean expression values across all 23 genes for each lab. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) model and results of the data analysis are shown at the bottom of the table.

Despite this heterogeneity, the correlation in gene expression across labs was generally quite high. Of the 10 possible pairwise correlations, 5 explained >50% of the variance in the ranking (i.e. r2>0.5), whereas 4 explained <33% variance (Table 3).

Another potential source of variation is between replicate samples within labs. Using the same set of labs, the correlation in the gene expression values within labs was the same, averaging 0.705 (vs 0.704 between labs; Table 3), with all values explaining >33% of the variance (and 5 out of 9 explaining >50% of the variance). However, it is clear that the consistency of replication within labs is relatively poor.

Discussion

We examined the expression levels of 15 TSGs and 8 POGs implicated in a high risk of familial cancer and found that a gene's highest expression was typically found in the tissue susceptible to the cancer with which it was associated. Specifically, the overall expression level was generally higher in susceptible tissue (or subtissue) compared with the average of nonsusceptible tissue for both TSGs (10 out of 15 TSGs, P<0.05) and POGs (7 out of 8 POGs, P<0.05) and, more importantly, that gene expression in the susceptible tissue (or subtissue) was within the highest expression group observed in 9 out of 15 TSGs (P<0.001) and in 5 out of 8 POGs (P<0.001). Despite the high level of variability in the data (see below), 3 TSGs and 3 POGs showed a level of expression significantly higher in their susceptible tissue (or subtissue) than in all 11 (or 12) other types (see Table 2). The remainder showed high expression in their susceptible tissue (or subtissue) that could not be statistically distinguished from levels in some other tissues; however, our statistical testing (via data resampling) incorporated this ambiguity in establishing the highly significant relationship between high expression and the susceptible tissue.

This relationship was predicted by the hypothesis of Weinberg (1988; Horowitz et al, 1990) that TSGs have been evolutionarily recruited in the susceptible tissues to suppress cancer and that this has occurred via upregulation of the expression of different genes in different tissues. This is a basic assumption of the model of Nunney (1999) for the evolution of cancer suppression: if a given cancer results in a significant loss of fitness, then natural selection will act on any genetic variation for tissue-specific expression of TSGs and POGs that results in a decrease in the occurrence of that cancer during the pre-reproductive and reproductive period.

Proto-oncogenes were found to show the same pattern as TSGs. This result could be due to POGs being recruited as additional cancer suppressors in a manner analogous to TSGs. This would require that each added POG adds one more necessary tissue-specific signalling pathway and hence one more ‘hit' in the progression of multistage carcinogenesis. An alternative possibility is that POGs generally have constitutively higher expression in the tissues in which they have a critical role in tissue development and maintenance (Sharma and Sen, 2013). If so, hereditary cancers arising from mutations in a specific POG occur because the tissue is especially sensitive to growth signals sent by that POG, or because such mutations have a bigger effect of perturbing some other potentially oncogenic cell function than mutations in a POG that is expressed at lower levels. The link between high expression and an important role in cell signalling is appealing, and may be a very general pattern; however understanding the potential role of POGs in the evolution of cancer suppression requires a comparative approach to determine whether larger, longer-lived organisms tend to have additional layers of highly expressed POGs associated with a given tissue.

A previous study (Lage et al, 2008) failed to find a consistent relationship between the expression of TSGs and POGs in susceptible relative to nonsusceptible tissues. They did find a trend towards overexpression of POGs in susceptible tissues consistent with our results; however, they also found a trend for the underexpression of TSGs in susceptible tissues. This difference is likely because of differences in methodology. For each gene–disease combination, the authors ranked the tissues by their degree of susceptibility based upon the number of times a tissue was co-mentioned in the PubMed literature with a disease of the given gene. The most highly mentioned 25 tissues were considered as the susceptible tissues for the given disease–gene combination in their statistical test. The use of 25 susceptible tissues for a given disease–gene combination is expected to mask the pattern that we were looking for: the evolutionary recruitment of cancer suppression in a very tissue-specific manner.

Our finding that the highest level of expression of a TSG or a POG generally occurs in the tissue susceptible to the oncogenic effects of that gene was highly statistically significant, but it was only established for 14 of the 23 genes examined. However, it is likely that our results are conservative given a range of biological and experimental factors that could act to mask the relationship between gene expression and cancer suppression activity. A number of experimental factors can cause unpredictable variation in the measures of gene expression. One important source of variation in expression that our study has highlighted is the precise nature of the tissue samples. The results of subtissue tests showed that in eight tests on TSGs where the susceptible tissue was not in the most highly expressed group, the outcome was reversed for four of the TSGs when the susceptible subtissue was used (Table 2). This result shows that reliable results can only be obtained when the specific cell type(s) that are susceptible to the cancer are examined.

Other important sources of experimental variation acting to mask general patterns were between-sample (within-lab) variation and between-lab variation. Within labs using the same subtissue, the average correlation in the expression of the 23 genes was r=0.705. This leaves 50% of the variance unexplained because of between-sample effects. When all within-lab expression values were averaged to minimise the between-sample variance and these averages were compared between labs, the correlation was not improved (r=0.704), highlighting substantial between-lab variation. This high level of between-lab variation (vs within-lab, between sample variation) was substantiated using ANOVA that revealed a highly significant lab(subtissue) × gene interaction (P<0.001; see Table 3). The same Affymetrix array was used by all labs and hence this was not the source of the variation. Many factors could contribute to both the between-sample and between-lab variation including the nature and physiological state of the patients sampled (gender, age, ethnicity, general health).

It may be possible to control for many of these factors in future studies by standardising tissue collection protocols, and by using either protein levels directly or higher quality gene expression data such as RNAseq. However, other biological factors may still act to mask the association between expression and tissue susceptibility. For example, some of these genes may only act as critical cancer suppressors, and thus be highly expressed, during certain periods of development. This possibility has been proposed (but not supported) in the relationship between the RB1 gene and retinoblastoma (Lee et al, 1988). In our study, two DNA-repair TSGs, MSH2 and BRCA1, both of which predispose to ovarian cancer, were found to have low expression in the ovaries, but extremely high expression in testes tissue. As ovarian tissues stop dividing before adulthood, but adult testes tissues continue to proliferate, the expression of these genes in ovarian tissues may be highest during early development. The small sample size of pre-adult tissues in our data set precluded the testing of this hypothesis. It would be useful to include tissue from different developmental stages (e.g., infant, child, adult) in future analyses. Alternatively, the failure to find elevated expression in the ovaries may be because of choosing an inappropriate susceptible tissue, as many high-grade serous ovarian tumours have been found to originate in the fallopian tube (Kurman and Shih, 2010).

In conclusion, our findings support the hypothesis that a high level of expression is a marker of oncogenic importance in both TSGs and POGs, as predicted under the model of Nunney (1999) for the evolution of cancer suppression. This approach has potential clinical applications. First, cancer-related genes showing unusually high expression in normal tissue can be examined further for a possible role in the sporadic cancers of that tissue. Second, the finding of high expression of a known TSG or POG in a particular cell type is a potentially useful tool for identifying candidate genes in our search for causes of familial cancers. Third, high expression can be used to determine the specific cell type involved in cancers that have unknown origin and yet the gene is known (such as rhabdoid tumours and SMARCB1). In addition, beyond the basic task of linking genes to cancers, mimicking or generating the signals from these genes may ultimately provide methods of cancer prevention for the susceptible tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carlo Maley and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable revisions. We also thank Sonia Peterson, Sasha Prokuda, Syed Ahmed and Derek O'Meara for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License

Supplementary Material

References

- Alimonti A, Carracedo A, Clohessy JG, Trotman LC, Nardella C, Egia A, Salmena L, Sampieri K, Haveman WJ, Brogi E, Richardson AL, Zhang J, Pandolfi PP. Subtle variations in Pten dose determine cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2010;42 (5:454–458. doi: 10.1038/ng.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AH, Knudson AG, Pandolfi PP. A continuum model for tumour suppression. Nature. 2011;476 (7359:163–169. doi: 10.1038/nature10275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignold LP. The cell-type-specificity of inherited predispositions to tumours: review and hypothesis. Cancer Lett. 2004;216 (2:127–146. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MA, Solomon E. Studies on inherited cancers: outcomes and challenges of 25 years. Trends Genet. 1997;13 (5:202–206. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunz F. Principles of Cancer Genetics. Springer: New York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elledge SJ, Amon A. The BRCA1 suppressor hypothesis: an explanation for the tissue-specific tumor development in BRCA1 patients. Cancer Cell. 2002;1 (2:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng C, Ponder BA. The role of gene mutations in the genesis of familial cancers. FASEB J. 1993;7 (10:910–919. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.10.8102106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER. Human cancer syndromes: clues to the origin and nature of cancer. Science. 1997;278 (5340:1043–1050. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenson B. A theory that explains the tissue specificity of BRCA1/2 related and other hereditary cancers. J Med Med Sci. 2010;1 (8:372–384. [Google Scholar]

- Friend SH, Bernards RA, Rogelj S, Weinberg RA, Rapaport JM, Albert DM, Dryja TP. A human DNA segment with properties of the gene that predisposes to retinoblastoma and osteosarcoma. Nature. 1986;323 (6089:643–646. doi: 10.1038/323643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung YK, Murphree AL, T'ang A, Qian J, Hinrichs SH, Benedict WF. Structural evidence for the authenticity of the human retinoblastoma gene. Science. 1987;236 (4809:1657–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.2885916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4 (3:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5 (10:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33 (Suppl 1:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JM, Park SH, Bogenmann E, Cheng JC, Yandell DW, Kaye FJ, Minna JD, Dryja TP, Weinberg RA. Frequent inactivation of the retinoblastoma anti-oncogene is restricted to a subset of human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87 (7:2775–2779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Shih IM. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34 (3:433–443. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf3d79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson AG. Hereditary cancers: clues to mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:661–666. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68 (4:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage K, Hansen NT, Karlberg EO, Eklund AC, Roque FS, Donahoe PK, Szallasi Z, Jensen TS, Brunak S. A large-scale analysis of tissue-specific pathology and gene expression of human disease genes and complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105 (52:20870–20875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810772105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EY, To H, Shew JY, Bookstein R, Scully P, Lee WH. Inactivation of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene in human breast cancers. Science. 1988;241 (4862:218–221. doi: 10.1126/science.3388033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindor NM, McMaster ML, Lindor CJ, Greene MH. Concise handbook of familial cancer susceptibility syndromes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008;38:3–93. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little CH. The relation of genetics to the problems of cancer research. Harvey Lect. 1923;17:65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh DJ, Dahia PL, Coulon V, Zheng Z, Dorion-Bonnet F, Call KM, Little R, Lin AY, Eeles RA, Goldstein AM, Hodgson SV, Richardson A, Robinson BG, Weber HC, Longy M, Eng C. Allelic imbalance, including deletion of PTEN/MMAC1, at the Cowden disease locus on 10q22-23, in hamartomas from patients with Cowden syndrome and germline PTEN mutation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;21 (1:61–69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199801)21:1<61::aid-gcc8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro AN. BRCA1: the enigma of tissue-specific tumor development. Trends Genet. 2003;19 (6:312–315. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Some Possible Bearings of Genetics on Pathology. New Era Printing Co: Lancaster, PA; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan LM, Kwok JB, Healey CS, Elsdon MJ, Eng C, Gardner E, Love DR, Mole SE, Moore JK, Papi L, Ponder MA, Telenius H, Tunnacliffe A, Ponder BAJ. Germ-line mutations of the RET proto-oncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Nature. 1993;363 (6428:458–460. doi: 10.1038/363458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunney L. Lineage selection and the evolution of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Biol Sci. 1999;266 (1418:493–498. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunney L. The real war on cancer: the evolutionary dynamics of cancer suppression. Evol Appl. 2013;6 (1:11–19. doi: 10.1111/eva.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R.1977Epidemiology, multistage models, and short-term mutagenicity tests The Origins of Human CancerHH Hiatt, JD Watson, JA Winsten, (eds)Vol. 41403–1428.Cold Spring Harbor Conferences on Cell Proliferation. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: New York [Google Scholar]

- Plevová P, Sedláková E, Zapletalová J, Křepelová A, Skýpalová P, Kolář Z. Expression of the hMLH1 and hMSH2 proteins in normal tissues: relationship to cancer predisposition in hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Virchows Arch. 2005;446 (2:112–119. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2008R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; ISBN 2-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org . [Google Scholar]

- Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF, Lewis DR, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2005. National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Seluanov A, Chen Z, Hine C, Sasahara TH, Ribeiro AA, Catania KC, Presgraves DC, Gorbunova V. Telomerase activity coevolves with body mass not lifespan. Aging Cell. 2007;6 (1:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seluanov A, Hine C, Azpurua J, Feigenson M, Bozzella M, Mao Z, Catania KC, Gorbunova V. Hypersensitivity to contact inhibition provides a clue to cancer resistance of naked mole-rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106 (46:19352–19357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905252106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Sen JM. Molecular basis for the tissue specificity of β-catenin oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2013;32 (15:1901–1909. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver DP, Livingston DM. Mechanisms of BRCA1 tumor suppression. Cancer Discov. 2012;2 (8:679–684. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton MR, Williams S, Fisher C, Ball A, Westbury G, Gusterson BA, Fletcher CD, Knight JC, Fung YK, Reeves BR. Structural alterations of the RB1 gene in human soft tissue tumours. Br J Cancer. 1989;60 (2:202. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varley JM, Evans DG, Birch JM. Li-Fraumeni syndrome—a molecular and clinical review. Br J Cancer. 1997;76 (1:1. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkitaraman AR. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell. 2002;108 (2:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10 (8:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA. Finding the anti-oncogene. Sci Am. 1988;259 (3:44–51. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0988-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA. The molecular basis of retinoblastomas. Ciba Found Symp. 1989;142:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA. The Biology of Cancer. Vol. 1. Garland Science: New York; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Welcsh PL, King MC. BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10 (7:705–713. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng-Bradley X, Rung J, Parkinson H, Brazma A. Large scale comparison of global gene expression patterns in human and mouse. Genome Biol. 2010;11 (12:R124. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-r124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilliox MJ, Irizarry RA. A gene expression bar code for microarray data. Nat Methods. 2007;4 (11:911–913. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.