Abstract

Objective

Focus on cancer survivorship and quality of life (QOL) is a growing priority. The aim of this study was to identify and describe the most salient psychosocial concerns related to sexual functioning among African-American (AA) prostate cancer survivors and their spouses.

Methods

Twelve AA prostate cancer survivors and their spouses participated in semi-structured individual interviews. The interviews assessed couples’ experiences with psychosocial adjustment and sexual functioning posttreatment for localized prostate cancer. The data were analyzed using the constant comparison method and content analysis.

Results

In this qualitative study of couples surviving prostate cancer, there were divergent views between the male prostate cancer survivors and their female partners, particularly regarding sexual functioning. For the males, QOL issues emerged as the primary area of concern, whereas survival of their husbands was considered most important among the female spouses. The male respondents expressed unease with the sexual side effects of their cancer treatment, such as erectile dysfunction and decreased sexual desire and satisfaction. Female spouses recognized decreased sexual desire in their partners following treatment, but this was not considered a primary concern.

Conclusions

Patients and their spouses may have differing perceptions regarding QOL and the impact of sexual functioning on survivorship. This study points to the need for further research and intervention development to address these domains with a goal to improve QOL.

Keywords: prostate cancer, cancer survivorship, psychosocial, sexual functioning, African-Americans, quality of life

Introduction

Eighty-nine percent of prostate cancers in African-American (AA) men are diagnosed at stages where the 5-year relative survival rate approaches 100% [1]. While more men are surviving prostate cancer, little is known about the psychosocial issues related to sexual functioning AA men experience due to prostate cancer treatment [1–4]. AA cancer survivors reportedly encounter multiple sociocultural barriers in seeking medical and psychosocial information, treatment, and care [5]. However, no studies to date have focused on AA men with prostate cancer and thus the applicability of these findings remains unclear.

An estimated 33–98% of prostate cancer survivors report poor quality of life (QOL) due to sexual dysfunction after treatment [6]. Common domains of sexual dysfunction include reduced sexual desire, erectile dysfunction (ED), and decreased sexual satisfaction [7]. These domains can produce psychological and relational stress and associated changes in survivors’ sex lives [8]. Several studies have identified negative psychological consequences commonly associated with treatment for prostate cancer, such as reduced feelings of masculinity, anxiety, depression, stress, and problems coping [9–11]. Other effects include diminished self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy and self-consciousness regarding sexual performance and the ability to sexually satisfy their partners, collectively resulting in a restricted and isolated lifestyle and embarrassment [5,12].

Recent studies have documented the adverse impact of prostate cancer treatment on a spouse’s QOL, which ultimately influences how effectively the couple copes with and adjusts to challenges of the illness [4,6]. Kim et al. refers to the interdependent impact of the QOL of one spouse and its impact on the other as an actor effect and partner effect [13]. This dyadic mutuality, described in the context of psychological distress, has also been described in other studies [14–17]. These studies show that spouses often report increased emotional and psychological stress, such as anxiety, depression, anger, fear, and loneliness, and are at increased risk of suffering greater psychological distress than the cancer patient [4,14–17].

This is the first known study to qualitatively examine and describe the psychosocial issues related to the sexual functioning of AA couples surviving prostate cancer. The study findings are part of a larger investigation of the salient psychosocial issues of AA prostate cancer survivors and their spouses and will assist in the development of culturally appropriate interventions to improve QOL.

Methods

Sample

A purposive sampling strategy was implemented to recruit participants. A sampling frame of 65 AA prostate cancer survivors was developed through the cancer registry of a major cancer center and the client network of a nonprofit state-based organization. Inclusion criteria for the male participants included: (a) diagnosed and treated for prostate cancer within the last 5 years and at least 1 year post-diagnosis; (b) age 40–70 years; (c) AA heterosexual, married male; and (d) no diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer or any other type of cancer. Couples were enrolled based on inclusion criteria for the male and the willingness of his spouse to participate.

Design

The study commenced upon approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of a major university. After informed consent procedures, semi-structured, in-person interviews were conducted with AA prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. The individual interviews with the couple were conducted concurrently to improve the validity of the responses, ensuring that data were not unduly influenced by the comments of one’s partner. The interviews were audio taped and professionally transcribed. At the completion of the interview, each interviewee received a $50 gift card to a local supercenter store, as approved by the IRB.

Interview guide

To establish content validity, the interview guide was pilot tested with a convenience sample of four AA couples treated for prostate cancer. Based on results from the pilot test and feedback from internal reviewers, the interview guide was revised by the study team. This revised interview guide was reviewed by clinical experts to establish face validity. The interview guide consisted of 8 primary interview questions and 15 possible probe questions.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using a combination of content analysis and the constant comparison method [18]. The study codebook consisted of a priori codes, derived from existing literature and emergent codes, identified as data analysis progressed. Two members of the study team coded each transcript independently, and codings were compared to ensure reliability. ATLAS.ti (version 5.2) software was used to manage and analyze the text produced during the interviews.

Results

Of the 65 AA eligible prostate cancer survivors contacted through an introductory letter, the response rate was 49%. Upon screening, 12 survivors were subsequently found eligible. Reasons for ineligibility include: (a) over the age of 70; (b) time since diagnosis and treatment was beyond study parameters; or (c) change of spouse since diagnosis and/or treatment. Male participants were between 51 and 70 years of age, with a mean of 59.75 years. Couples were married throughout prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment, and the length of marriage ranged from 5 to 46 years.

Among the 12 couples, surgery and radiation were the most common forms of treatment, with 33.3% (four) reporting surgery, 42% (five) reporting radiation therapy, and 25% (three) reporting a combination of surgery and radiation therapy. Of the eight individuals who received radiation therapy, 88% (seven) reported having brachytherapy or seed implants. For the 11 couples reporting ED, some form of oral medication was recommended. The couple that reported no ED described some decreased libido and was the only couple that underwent hormone therapy. Five of the 12 couples discussed changes in libido following prostate cancer treatment.

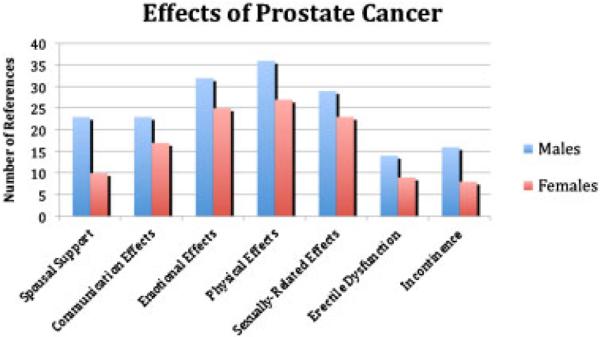

In the following section, a summary of key themes is discussed in the context of sexual functioning. Figure 1 reflects the frequency of reporting key themes between the men and their spouses. The broad range of convergent and divergent psychosocial concerns identified by the men and their spouses are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Effects of prostate cancer treatment on African-American couples

Table 1.

Perceived psychosocial concerns of prostate cancer among African-American survivors and their spouses

| Themes | Male prostate cancer survivors | Female spouses |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual functioning | Concern about loss of sexual desire and performance | Concerns for husband’s wellness |

| ‘It takes away your sex drive and it changes your lifestyle.’ | ‘It affected that way (sexually), but… we love each other so it didn’t have a big barrier… the main thing was him being cured.’ |

|

| ‘You don’t have any feelings… for sex [sexual desire]… That really upset my whole life.’ |

‘When he was first diagnosed, my main concern was to save his life.’ |

|

| ‘I know I do need some help to get an arousal… but it varies and (my doctor) recommends (one kind of drug) for that and another for maintaining and I wanna get with it but it may just be gone.’ |

‘I think one of the biggest problems once a man finds out he has prostate cancer… he’s thinking that’s the end of his sex life. To some men that’s the same as the end of their whole life.’ |

|

| ‘Sometimes inside of me I feel like I want to make love… but it’s not there… so I just block it out of my mind.’ |

‘He has mood swings if he can not perform… it gets to him… it’s hard for me seeing him upset.’ |

|

| ‘I’m not happy with the way it turned out… it’s been 4 years and still can’t have a sex drive.’ |

||

| Communication | Focus on difficulties with patient– provider communication | Focus on difficulties with partner communication |

| ‘They tell you to accept it or at least it could happen… so you sit and wait for it to happen.’ |

‘I don’t know if he talked to the doctor about like a penile implant or anything to help. He never explains to me what he wants.’ |

|

| ‘I was given a few prescriptions so I guess they knew it might be a problem.’ |

‘We know part of him is not there… but he didn’t explain that he would like to have things like that (Viagra)… and I don’t think he will’ |

|

| ‘They told me it’ll take time for your nature to come back to you… I didn’t know what to expect… I think they should have explained it a little better to me.’ |

‘They put him on Viagra and I don’t know what else to tell you, cause that’s all I know… he don’t say nothing or do nothing so what am I gonna do?’ |

|

| ‘They told me I might have… some impotence [erectile dysfunction], but not that I could not get no erection.’ |

||

| Social support | Spouse’s support regarding sexual functioning | Change in sexual relationship with spouse |

| ‘My wife go along with me, sex is out of the question… she don’t worry about it and I don’t worry about it.’ |

‘We used to travel… go all the time… that was our alone time… he don’t plan no trips with me no more… don’t do nothing.’ |

|

| ‘I think she may have lost some interest [at time of diagnoses]— that’s the way I felt, but I don’t know how she really felt. She never said it.’ |

‘Sexually, I’m not attracted to him because of it [i.e. erectile dysfunction]’ |

|

|

Management

techniques |

Lack of effective treatments for erectile dysfunction | Minimal information about prostate cancer treatment |

| ‘They try to give me pills… I try some needle stuff… still don’t work.’ |

‘He’s tried Viagra, and he says it doesn’t do him much good.’ | |

| ‘I’m scared to take those pills… I take enough medications.’ | ‘He took it the first time, said his head hurt and so there’s no sex life.’ |

|

| ‘I took ‘em, they don’t work… so what’s the point?’ | ‘Condoms but that was all.’. | |

| ‘They try to give me pills… where I could live my life but it just don’t work.’ |

‘I was pretty upset… I asked the doctor what is this gonna do to his sex life… and he really never addressed it…’ |

|

|

Marital role

delineation |

Affect on masculinity and manhood | Impact of marriage commitment and affection |

| ‘You lose your confidence… that’s the biggest thing in a man’s life… he’s like a nobody, he’s a peon… it’s a drawback, always on your mind.’ |

‘It’s different… I mean, you have sex but you don’t have to have sex all the time to love a person, you know.’ |

|

| ‘The (lack of) erections are what’s holding me back on everything. My sexual activity was a big part of my life you know cause I’m a man that’s just nature.’ |

||

| Temporal orientation | Self-evaluation of purpose and meaning of life | Impact of length of time married |

| ‘I guess most men my age… don’t know if… it’s age or what… I always been a active man all my life but now not quite as much… and it doesn’t bother me… anymore.’ |

‘Because of our age and the many years we’ve been together, it’s not a problem…’ |

|

| ‘I kinda block that (sex) out of my mind… like I said, I’m 69 years old and I had enough fun in my life… so one way or another, you gotta give up certain things.’ |

‘You know, a lotta people think sex is everything but when you start getting older then you start realizing a lotta different things about sex; you understand what I’m sayin.’ |

|

| ‘I’m not a young man and eventually it’s (sex) gonna stop anyway so I’m not really worried about it.’ |

Males’ perceptions of sexual functioning

When asked to describe the impact of prostate cancer treatment on their sexual relationships, the male participants frequently discussed ED as a primary side effect of treatment, contributing to increased distress and either temporary or permanent sexual dysfunction. Most men noted having reduced ability to perform sexually. Some of the participants discussed how the loss of sexual desire or reduced capacity to perform sexually due to ED influenced their sense of masculinity or manhood, resulting in decreased self-confidence and self-esteem.

For some of the men, ED was a topic of concern because they had been informed before treatment to anticipate such side effects by their physician or in literature regarding prostate cancer treatment. However, some men felt they did not have enough information about the possibility of ED. Most of the male participants felt they were given many options about ways to manage ED but without counseling or in-depth detail on each option. Many were frustrated that these options did not seem to work. About half of the men were reluctant to use any type of ED treatment or management. Oral medications were the most frequently mentioned treatment option for ED. Among those who had tried oral medications, most expressed disappointment in the results achieved and no longer used them.

Men stated the support of their spouse, family, and friends was beneficial during the diagnosis and treatment of their cancer, yet they rarely reported open communication about their treatment and symptoms with their spouses. A small minority of men reported discussing either potential or actual loss of sexual functioning with their wives. However, most men seemed to speculate how their wives felt, suggesting a lack of discussion about their sexual challenges. Some male participants were less concerned about their decreased ability to have an erection or, in some cases, the total loss of sexual desire, owing to the encouragement and support received from their spouse. The majority of men, even those who said sex was not important or their relationship with their spouse was still good without sex, appeared conflicted or concerned about the loss or reduction of this aspect of their lives.

Females’ perceptions of sexual functioning

Although sexual functioning emerged as an area of concern, the survival of their husbands was considered most important among the female spouses. The majority of women recognized decreased sexual desire in their partners following prostate cancer treatment. These same women noted they were unsure of the etiology of the loss or decrease in sex drive.

The women conveyed their distress and frustration given their limited knowledge of prostate cancer, minimal communication about their partners’ treatment, and the lack of support and services for partners of cancer patients. Most women reported their spouse had tried some type of oral medication or procedure to regain or retain erectile functioning, but they were sometimes unfamiliar with the details of their partner’s treatment. About half of the women noted the physician only mentioned sex as part of discussions about the need to use condoms immediately after prostate seed implants (i.e. radiation). Minimal information was communicated to the spouses regarding their husband’s treatment options and/or available services.

Approximately half of the women said the reduced sexual desire and sexual activity were not problematic. Often, this was attributed to the couples’ age, the length of the time the couple has been together, and/or the level of commitment of the couple. Instead, most women said they were more concerned about their husband’s distress over the loss of sexual functioning than they were for themselves. However, some were unaware of their husband’s true feelings due to limited discussions about sexual functioning. A few women reported some conflict over the loss of sexual activity in their relationship; yet, they had difficulty articulating these feelings.

Discussion

The findings of this exploratory study are generally consistent with earlier QOL research in prostate cancer and other disease sites, linking increased psychosocial morbidity with sexual dysfunction. This study is among the first to qualitatively describe the psychosocial issues of sexual dysfunction from the perspective of AA couples. Although the husbands in this study tended to focus on sexual dysfunction as the source for most of their posttreatment distress, the intrinsic link of social relationships, sexuality, and manhood was of more concern. The majority of men discussed the impact of decreased sexual functioning on their overall concept of masculinity, confidence, self-esteem, and their ability to relate to their spouses. The wives noted the change in self-esteem and confidence among their husbands following treatment. As a result of this change in masculinity and sexuality, the husbands reported an increase in psychological distress, feelings of social isolation, and an inability to communicate with their spouses.

Our findings represent a unique contribution to the literature, providing new information on the role of sociocultural factors, such as seeking medical information, social support, communication strategies, management techniques, marital role delineation, and temporal orientation, related to psychosocial issues of sexual dysfunction among AA men and their spouses. The majority of couples reported an increased need for social support, but was hampered by ineffective communication and coping strategies. Couples reported minimal exchanges between each other regarding the extent and impact of the effects of treatment on overall QOL. Similar to other studies, the husbands reported frustrations with their relationships and often found it difficult to share their concerns with their wives [19,20]. Additionally, couples agreed that being part of a strong, positive, committed, and supportive relational dyad with good communication skills could serve as a buffer against psychological distress. The lack of available information was found to adversely impact the couples’ ability to effectively communicate and cope with the effects of treatment. Wives also expressed an interest in being involved in the treatment decision-making process, given their role as the primary caregiver.

Conclusions

The exact impact and extent of successful adaptation of changes in body and self-image, masculinity, sexuality, and uncertainty remains unclear among AA prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. This study of AA couples surviving prostate cancer highlights the need for more indepth investigations of psychosocial issues, in general, and sexual functioning, in particular.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Stasha Roberts and Will Tarver for their support and assistance during this study. This research was supported in part by funding from the American Cancer Society, Institutional Research Grant #60132530120.

Footnotes

This article was published online on February 24, 2010. An error was subsequently identified in the author affiliations. The publishers wish to apologise for this error. This notice is included in the online and print versions to indicate that both have been corrected [April 16, 2010].

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures for African Americans, 2009–2010. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council . In: From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Committee on Cancer SurvivorshipHewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garos S, Kluck A, Aronoff D. Prostate cancer patients and their partners: differences in satisfaction indices and psychological variables. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1394–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powe BD, Hamilton J, Hancock N, et al. Quality of life of African American cancer survivors: a review of the literature. Cancer. 2007;109:435–445. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: exploring the meanings of ‘erectile dysfunction’. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders S, Pedro LW, Bantum EO, Galbraith ME. Couples surviving prostate cancer: long-term intimacy needs and concerns following treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10:503–508. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassouna MM, Heaton JP. Prostate cancer: 8 urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Can Med Assoc J. 1999;160:78–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berteroö C. Altered sexual patterns after treatment for prostate cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9:245–251. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009005245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lev EL, Eller LS, Gerjerman B, et al. Quality of life of men treated with brachytherapies for prostate cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirl WF, Mello J. Psychological complications of prostate cancer. Oncology. 2002;16:1448–1453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visser A, van Andel G, Willems P, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life of men with prostate cancer 3 months after diagnosis: the role of psychosocial factors and comparisement with benign prostate hyperplasia patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:225–232. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler L, Downe-Wamboldt B, Marsh SD, Jarvi K. Quality of life post-radical prostatectomy: a male perspective. Urol Nurs. 2001;21:282–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw CK, Smith TG. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:230–238. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soloway CT, Soloway MS, Kim SS, Kava BR. Sexual, psychological and dyadic qualities of the prostate cancer ‘couple’. BJU Int. 2005;95:780–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couper J, Bloch S, Love A, Macvean M, Duchesne GM, Kissane D. Psychosocial adjustment of female partners of men with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:937–953. doi: 10.1002/pon.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manne S, Babb J, Pinover W, Horwitz E, Ebbert J. Psychoeducational group intervention for wives of men with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:37–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl. 1965;12:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harden J, Schafenacker A, Northouse L, et al. Couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: focus group research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:701–709. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.701-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banthia R, Malcarne VL, Varni JW, Ko CM, Robins Sadler G, Greenbergs HL. The effects of dyadic strength and coping styles on psychological distress in couples faced with prostate cancer. J Behav Med. 2003;26:31–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1021743005541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]