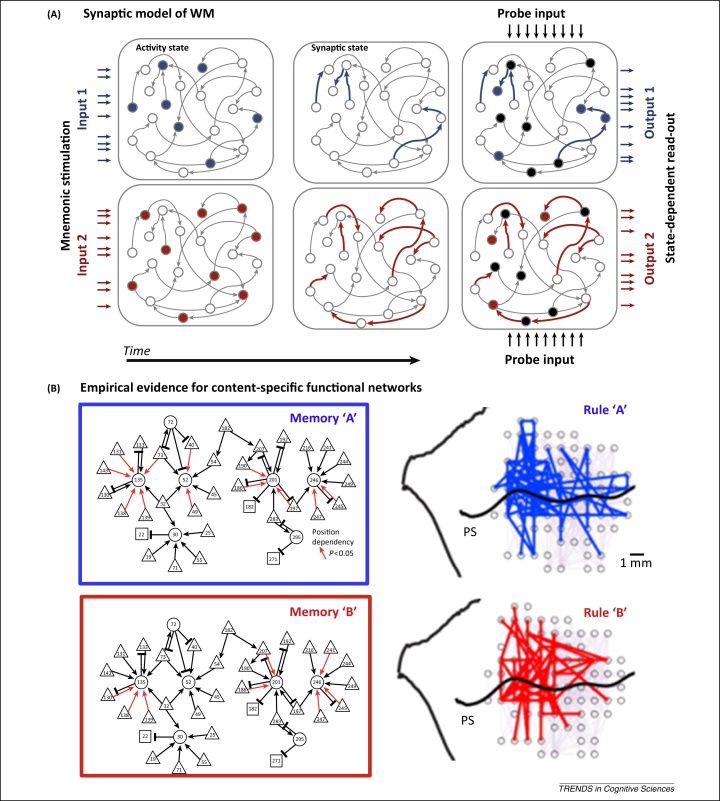

Figure 2.

Maintaining ‘activity-silent’ working memory (WM) in functional connectivity. (A) Schematic of the synaptic model of WM described in [23]. Task-relevant input (left-side horizontal arrows, blue for ‘Memory A’ and red for ‘Memory B’) drives a stimulus-specific activity state (filled circles) that in turn triggers a specific pattern of short-term synaptic plasticity between cells (bold arrows). Memory is read out from this synaptic trace via the context-dependent response at retrieval (black filled circles, same for ‘Memory A’ and ‘Memory B’). The probe-driven response will be patterned by the hidden state of synaptic efficacy, resulting in a discriminable output pattern (right-side horizontal arrows). (B) Empirical evidence for content-specific functional networks. Simultaneous recordings in rat frontal cortex revealed direction-specific patterns of synaptic efficacy (red arrows) between cells [putative pyramidal (triangles); putative interneuron (circle); unclassified (square)], encoding direction during a WM-based maze task (left panel; adapted from [34] with permission from Nature Publishing Group). This is consistent with a role for short-term synaptic plasticity in WM. In the monkey prefrontal cortex (PFC) (PS, principal sulcus), different task rules are associated with specific functional networks (synchronised electrodes for rule ‘A’ in blue, rule ‘B’ in red) coupled by synchrony at ∼30 Hz (left panel; adapted from [36]). This is consistent with the idea that coherence could also play a role in constructing functional networks for flexible behaviour.