Abstract

We study the Medicare Part D prescription drug insurance program as a bellwether for designs of private, non-mandatory health insurance markets, focusing on the ability of consumers to evaluate and optimize their choices of plans. Our analysis of administrative data on medical claims in Medicare Part D suggests that fewer than 25 percent of individuals enroll in plans that are ex ante as good as the least cost plan specified by the Plan Finder tool made available to seniors by the Medicare administration, and that consumers on average have expected excess spending of about $300 per year, or about 15 percent of expected total out-of-pocket cost for drugs and Part D insurance. These numbers are hard to reconcile with decision costs alone; it appears that unless a sizeable fraction of consumers place large values on plan features other than cost, they are not optimizing effectively.

Keywords: Medicare, prescription drugs, health insurance demand

1. Introduction

Medicare Part D gives the Medicare-eligible population of seniors access to a subsidized market for non-mandatory standardized prescription drug coverage through contracts sponsored by private insurance firms and approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This market, which began operation in 2006, is representative of a trend toward “consumer-directed healthcare” that relies on consumer behavior and competition among insurers and accountable care organizations to attain satisfactory allocation of health care resources with limited government regulation. It is one model for more comprehensive reform of health care insurance (see Newhouse, 2004; Bach and McClellan, 2005; Buntin et al., 2006; Goodman, 2006; and the references therein). Overall, Medicare Part D is considered a success story: Despite a rocky start, enrollment rates are high1, consumers have a broad choice of insurers, and premiums are lower than anticipated by policymakers and insurers (Heiss, McFadden, and Winter, 2006, 2007; Goldman and Joyce, 2008; Duggan, Healy, and Scott-Morton, 2008).2

Despite these successes, making optimal, or even just reasonable, decisions in the Part D market is difficult for seniors. Individuals who are not on employer retirement plans or low-income subsidies have to decide whether to enroll in Part D, and if they do enroll must choose among more than 30 competing stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans (PDP) in most Medicare regions, or alternately Medicare Advantage (MA) plans that bundle a prescription drug benefit with health maintenance coverage. In evaluating plans, individuals face uncertainty with respect to their future health status and drug needs, and rather complicated benefit schedules and formularies, including a coverage gap in most PDP plans and other peculiar institutional features of the Part D program described later in some detail. To navigate these decisions successfully, consumers need to know their current health conditions and drug use, and understand the risk that they will have different drug needs in the future; they need to process this information together with plan features to form realistic expectations regarding drug-related expenditures under alternative plans; and they need to adopt a decision-making protocol that accounts for expected costs and risk, and maximizes their preferences. Failure to choose a good plan could result from violation of any of these elements.

Poor plan choices by seniors can obviously reduce individual welfare, and offset the potential gain from having menus of alternatives. Further, failure of consumers to consistently “vote with their feet” and reject inferior plans blunts the market pressure on insurers to operate efficiently.3 Part D is an informative experiment on how consumers behave in real-world decision situations with a complex, ambiguous structure and high stakes, and may yield predictions for how they will handle plan choices in the new general health insurance exchanges that will implement the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

The quality of plan choice was considered a major issue from the start of the Part D program (see, e.g., Neuman and Cubanski, 2009). How seniors decide whether to enroll in Medicare Part D and what plans they select determines the impact of CMS policies regarding the entry and offerings of insurers in the Part D market: regulation of formulary and benefit designs (FBD); information provided by the government to consumers, pharmacists, and providers; and regulation of the content and scope of marketing by insurers. CMS has undertaken an extensive program of outreach to provide relevant information and guidance to consumers. In particular, these efforts include its Plan Finder, an internet tool that gives the available plans, premiums, and out-of-pocket costs for any list of prescription drugs (her “medicine cabinet”) specified by the consumer. This tool can help consumers collect and process relevant information on predicted needs, and if consumers pay attention to Plan Finder’s recommendations, remove an important source of poor plan choices. Other flaws in decision-making, such as inattention and procrastination, may require different interventions, for example auto-enrollment with Plan Finder recommendations as defaults while allowing consumers to opt out or override. We return to these issues in the concluding section.

In this paper, we examine how well consumers did in choosing their Medicare Part D insurance plan in the first few years of the program. We use the 20% samples of Medicare claims records that have recently become available for scientific research to construct working samples of Medicare enrollees in stand-alone Part D plans for the years 2006, 2007, and 2008. The size of the dataset – our yearly analysis samples comprise about 1.2 million observations – allows for a great level of detail in the construction of drug use and cost variables. For the individuals in these samples, we compute total drug-related costs for their chosen plans and for all the plans that were available to them. We then calculate the ex ante losses from not choosing optimal plans. For this purpose, we develop an expected utility framework that allows for uncertainty about drug needs in the coming year. We also study alternative decision rules and assumptions with respect to expectations formation.

A number of papers have considered the quality of plan choices in Medicare Part D, but mostly with rather specific or small samples, and also with somewhat inconsistent findings. We briefly review three recent studies, and refer the reader to these papers for additional references.4

Abaluck and Gruber (2011) use comprehensive pharmacy data provided by Wolters Kluwer that cover almost one-third of all third-party prescription drug transactions. They match these data with information on the characteristics of all the plans available to the individuals in the dataset. Abaluck and Gruber find that in their plan choice, individuals place more weight on plan premiums than on expected out-of-pocket costs. Also, individuals value plan financial characteristics in excess of their possible impacts on financial expenses or risk, while placing almost no value on variance-reducing aspects of plans.

Ketcham et al. (2012) analyze a large data set from a “single insurer that sells Part D plans (PDPs) and administers PDPs sold by other companies”. The data contain information on individuals’ chosen and available plans, prescription drug use and spending, and other characteristics. Their analysis focuses on the issue of whether the choices of Medicare Part D enrollees improved over the first two years of the Medicare Part D program in terms of reducing overspending, defined as “the consumers annual ex post out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for insurance and prescription drugs above the cost of the cheapest alternative, where the alternatives include other Part D plans as well as having no coverage”. They find large reductions in ex post overspending from 2006 to 2007, which they attribute mostly to plan switching. These findings contrast with those of Kling et al. (2012) who argue that consumers’ choices are subject to substantial “comparison frictions” and arrive at a more pessimistic conclusion about consumers’ ability to choose the best plans.

Zhou and Zhang (2012) show that in 2009, only 5.2 percent of beneficiaries chose the cheapest Medicare Part D plan (given their current drug needs). They use a 5 percent sample of Medicare Part D claims together with publically available formulary data. Since their approach and data are generally similar to ours but they arrive at slightly different findings, we return to that paper when we present our results in section 4.3.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we describe the data and the approach taken for simulating the relevant attributes of alternative plans available to each consumer. We use Medicare administrative data on drug spending to characterize Part D enrollment decisions in Section 3. In Section 4, we present an analytical framework for analyzing ex ante and ex post optimization failures, along with the results. Section 5 concludes.

2. Data

In this section, we first describe in Section 2.1 the construction of our working samples. Section 2.2 then describes how we simulate the relevant costs consumers face under alternative plans; this includes constructing the plan formularies (which are not publically available in the years of our analysis) from the universe of claims records. We check the validity of these simulations in section 2.3. The use of claims data, the rather complex structure of Medicare Part D, and the lack of publically available formulary information for Part D plans, made these constructions demanding. We document our procedures in some detail; additional information can be found in the appendices.

2.1 Data sources and definition of working samples

This study is based upon the Medicare claims records of a 20 percent representative sample of the approximately 45 million people enrolled in Medicare in the years 2006, 2007, and 2008. Each person enrolled in Medicare has a Health Insurance Claim (HIC) code, which they retain for life (tracked through a change in the HIC code of their primary beneficiary when necessary). The sample, obtained from CMS under a special data use agreement, selects all enrollees with HIC codes ending in ‘0’ or ‘5’; this includes 9,086,340 Medicare beneficiaries in 2006; 9,299,848 in 2007; and 9,530,609 in 2008. People enrolled in any year appear longitudinally across all the years in which they are enrolled by virtue of retaining their HIC code with the same terminal digit. The sample grows each year as new people become eligible to enroll (primarily by reaching age 65 or developing a qualifying disability), and shrinks as people become ineligible (primarily through death or recovery from a qualifying disability).

The sample data include Medicare Parts A and B claims records for 2002–2008, and Part D claims records for 2006–2008, censored to the left for persons who initially enroll in Medicare before 2002, and censored to the right for persons whose enrollment ends after 2008. A major advantage of the claims data is the size and representativeness of the sample; a drawback is that these administrative records contain no clinical data on medical conditions, very limited data on the socioeconomic status of enrollees, and no data on risk preferences, perceptions, or decision-making circumstances that might be used to identify social or behavioral sources of poor plan choices.

To study Part D plan choices of seniors, we form working samples of Part D enrollees who have unrestricted choice among all the plans available in their Medicare region, and have sufficient data on their health, drug use, out-of-pocket costs, and premiums to evaluate the quality of their plan choices. These working samples include 1,139,469 people in 2006, 1,249,301 in 2007, and 1,307,396 in 2008. The working samples screen out (1) persons under age 65, (2) persons who do not qualify for Medicare benefits because they live outside the U.S., (3) persons not enrolled in Part D, (4) enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans, (5) persons who are dual-eligible5 or on low-income subsidies (LIS), (6) persons on retiree plans who do not have unrestricted plan choice, (7) persons who are not enrolled in continuous Part D stand-alone plan coverage throughout the year, (8) persons who are enrolled in employer group waiver (EGWP) plans, and (9) persons who are without prior year claims information (when the analysis requires this information).6

Screens (1) and (2) define our target population; we exclude people under age 65, who are on Medicare due to institutionalization or qualifying disabilities, because their health is quite different from that of the senior population. Screen (3) excludes Part D non-enrollees, and screen (4) excludes Medicare Advantage enrollees, because their claims records to not include comparable data on health conditions and drug use. Screens (5) and (6) exclude people who have restricted choice alternatives and subsidized costs. Enrollees who pass screens (1) through (6) are all enrolled in stand-alone PDP. Screens (7) through (9) exclude people with incomplete information on drug options, cost, or use. Our final working sample records contain Part D enrollment status and (encrypted) plan choice in each of the years 2006, 2007, and 2008, and all prescription drug claims, including medications, benefits paid, total prescription costs, and copayments.

The screens that define our working samples are substantive selections from the overall age 65+ target population. First, they exclude people who (endogenously) choose either no drug coverage or a Medicare Advantage plan that includes drug coverage. Second, they exclude people who have drug coverage through a channel in which they do not see the full premiums, copayments, and alternatives of stand-alone PDP. Third, they exclude people who become newly eligible for Medicare within the year, people who die before the end of an enrollment year, and people who switch into or out of Medicare Advantage coverage voluntarily or as a result of institutionalization. Thus, our working samples under-represent new Medicare enrollees because we have insufficient observed health history to evaluate their choices; this is an issue because initial Plan D choice may have a strong influence on subsequent choices due to inertia and switching costs. Our samples also under-represent terminal enrollees who in the last year of life are likely to incur new health conditions and drug needs. We find that the selected populations from which the working samples are drawn have higher shares of females and whites, and more chronic health conditions, than the overall age 65+ population; this is attributable primarily to the exclusion of people on retiree health plans. Thus, our working samples contain people with relatively well-defined and complete plan choice sets. Conclusions about plan choice behavior from these samples do not necessarily generalize to the overall population of seniors. However, our samples avoid significant self-selection and coverage issues in populations such as the customers of specific pharmacy chains that have been sources of samples used in earlier research.

Appendix A details the selection process, with Table A1 giving the number of people remaining after each screening step, with their average age, the shares of females and of whites, and the average number of chronic health conditions. Because of the screens we apply, the numbers of beneficiaries at various steps in Table A1 do not match up directly with published statistics. Consider the 20 percent sample in 2007. Of the 9,299,848 beneficiaries on the denominator file, 87 percent are identified as having some form of prescription drug coverage at some point in 2007. This is a little less than the 90 percent coverage rate targeted by CMS and achieved in various enrollment reports; the difference may be under-reporting in the denominator file of some forms of coverage that are counted by CMS in total coverage, or exclusion of some denominator file groups in the reporting of coverage rates. The share of the 9,299,848 beneficiaries with Part D coverage at some point in 2007 is 56.1 percent, and with Part D coverage throughout the year is 48.7 percent. These shares exclude individuals with creditable or retiree coverage who are not enrolled in Part D, and individuals who move between stand-alone Part D and other plans (e.g., Medicare Advantage), or who become newly eligible during the year. Table A2 gives a breakdown by age of the patterns of part and full-year Medicare enrollment, and indicates the selection resulting from screening new enrollees and terminal enrollees from our working samples.

Table A1.

Definition and properties of working samples

| Number | % Total | Age | % Female | % White | # chronic conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | ||||||

| Total | 9,086,340 | 100 | 70.7 | 55.7% | 83.6% | |

| U.S. residents aged 65+ | 7,120,960 | 78 | 75.3 | 57.7% | 85.7% | |

| Enrolled in Part D | 3,764,474 | 41 | 75.6 | 63.2% | 82.3% | |

| Enrolled in standalone Part D Plan (PDP) | 2,639,297 | 29 | 75.8 | 65.3% | 82.4% | 1.68 |

| Non dual-eligible, Non-LIS | 1,466,200 | 16 | 75.0 | 62.5% | 94.2% | 2.68 |

| Non-employer group waiver plan | 1,332,955 | 15 | 75.0 | 63.1% | 94.3% | 2.90 |

| Continuously enrolled | 1,139,469 | 13 | 75.2 | 63.8% | 94.7% | 3.18 |

| Prior year data available | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2007 | ||||||

| Total | 9,299,848 | 100 | 70.6 | 55.5% | 83.4% | |

| U.S. residents aged 65+ | 7,235,063 | 78 | 75.3 | 57.5% | 85.5% | |

| Enrolled in Part D | 4,003,149 | 43 | 75.6 | 62.6% | 82.5% | |

| Enrolled in standalone Part D Plan (PDP) | 2,712,376 | 29 | 75.9 | 64.7% | 82.6% | 2.14 |

| Non dual-eligible, Non-LIS | 1,535,704 | 17 | 75.0 | 62.1% | 93.8% | 3.35 |

| Non-employer group waiver plan | 1,418,070 | 15 | 75.0 | 62.6% | 94.1% | 3.57 |

| Continuously enrolled | 1,249,301 | 13 | 75.2 | 63.4% | 94.6% | 3.83 |

| Prior year data available | 1,147,353 | 12 | 75.4 | 64.0% | 94.8% | 3.93 |

| 2008 | ||||||

| Total | 9,530,609 | 100 | 70.5 | 55.3% | 83.2% | |

| U.S. residents aged 65+ | 7,403,722 | 78 | 75.2 | 57.3% | 85.4% | |

| Enrolled in Part D | 4,215,955 | 44 | 75.5 | 62.0% | 82.7% | |

| Enrolled in standalone Part D Plan (PDP) | 2,749,743 | 29 | 75.8 | 64.2% | 82.8% | 2.46 |

| Non dual-eligible, Non-LIS | 1,589,870 | 17 | 75.0 | 61.5% | 93.8% | 3.48 |

| Non-employer group waiver plan | 1,450,372 | 15 | 75.0 | 62.1% | 94.2% | 3.74 |

| Continuously enrolled | 1,307,396 | 14 | 75.2 | 63.0% | 94.6% | 4.02 |

| Prior year data available | 1,230,347 | 13 | 75.4 | 63.5% | 94.7% | 4.10 |

Table A2.

Medicare enrollment by age in 2007

| Age January 2007 | stayers | entrants | leavers (death) | Leavers (other) | entrants and leavers (other) | entrants and leavers (death) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start: | January | After January | January | January | After January | After January |

| Stop: | December | December | Before December | Before December | Before December | Before December |

| 64 | 98,214 | 393,088 | 2,704 | 24 | 71 | 1,435 |

| 65 | 444,480 | 4,720 | 5,934 | 88 | 17 | 9 |

| 66 | 421,186 | 2,016 | 6,198 | 79 | 9 | 6 |

| 67 | 402,074 | 1,243 | 6,193 | 70 | 11 | 7 |

| 68 | 395,671 | 972 | 6,753 | 77 | 5 | 3 |

| 69 | 374,095 | 831 | 6,985 | 66 | 5 | 3 |

| 70 | 355,531 | 602 | 7,258 | 58 | 7 | 6 |

| 71 | 345,095 | 535 | 7,784 | 77 | 9 | 2 |

| 72 | 330,193 | 435 | 8,298 | 86 | 6 | 2 |

| 73 | 306,904 | 355 | 8,434 | 73 | 5 | 1 |

| 74 | 306,732 | 357 | 9,154 | 80 | 5 | 4 |

| 75 | 295,700 | 324 | 9,600 | 86 | 2 | 4 |

| 76 | 293,876 | 250 | 10,578 | 102 | 8 | 2 |

| 77 | 273,060 | 221 | 10,660 | 76 | 7 | 5 |

| 78 | 265,997 | 211 | 11,437 | 82 | 2 | 2 |

| 79 | 256,164 | 146 | 12,335 | 87 | 0 | 4 |

| 80 | 237,797 | 125 | 12,633 | 91 | 4 | 2 |

| 81 | 223,355 | 124 | 13,321 | 70 | 0 | 2 |

| 82 | 210,338 | 99 | 13,925 | 73 | 1 | 4 |

| 83 | 189,343 | 81 | 13,754 | 77 | 0 | 2 |

| 84 | 171,297 | 56 | 13,977 | 75 | 2 | 2 |

| 85 | 157,259 | 65 | 14,348 | 63 | 0 | 2 |

| 86 | 134,761 | 41 | 13,946 | 57 | 0 | 2 |

| 87 | 108,484 | 39 | 12,474 | 45 | 1 | 0 |

| 88 | 95,107 | 23 | 12,449 | 36 | 0 | 1 |

| 89 | 77,746 | 23 | 11,273 | 25 | 1 | 0 |

| 90+ | 295,594 | 63 | 60,510 | 41 | 0 | 3 |

Source: Tabulations from 20% sample of Medicare enrollees

For people in the 20 percent sample facing a plan choice in an end-of-year enrollment period, we use indicators of health conditions from the Chronic Condition Warehouse classification and coding provided by CMS, described in Appendix A. Table A3 lists these health conditions, and their prevalence in the working samples; these are basis for the counts of health conditions that appear in Table A1.7

Table A3.

Health conditions and working sample prevalence

| Chronic condition | Reference Time Period (# years) | Number/Type of Claims to Qualify | Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |||

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | 1 | 1 inpatient claim | 2.0% | 2.8% | 3.1% |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 3 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 2.4% | 3.5% | 3.6% |

| Alzheimers Disease, Senile Dementia, Related Disorders | 3 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 5.5% | 7.8% | 8.1% |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/Carrier claims | 9.7% | 12.5% | 12.9% |

| Breast Cancer | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 3.5% | 4.3% | 4.5% |

| Cataract | 1 | 1 HOP/carrier claim | 49.4% | 59.0% | 61.2% |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 2 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 7.0% | 10.5% | 12.2% |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 12.5% | 16.3% | 17.1% |

| Colorectal Cancer | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 1.5% | 2.0% | 2.1% |

| Depression | 1 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 12.7% | 16.9% | 18.2% |

| Diabetes | 2 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 20.6% | 26.1% | 27.5% |

| Endometrial Cancer | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Glaucoma | 1 | 1 carrier claim | 14.8% | 18.0% | 18.9% |

| Heart Failure | 2 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 14.3% | 19.1% | 19.7% |

| Hip/Pelvic Fracture | 1 | 1 impatient claim | 1.5% | 2.2% | 2.4% |

| HIV/AIDS | 1 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 64.6% | 76.6% | 77.6% |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 2 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 32.6% | 40.4% | 41.7% |

| Lung Cancer | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 0.6% | 0.9% | 1.0% |

| Osteoperosis | 1 | 1 inpatient or HOP/carrier claim | 23.8% | 29.3% | 30.9% |

| Prostate Cancer | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 3.7% | 4.5% | 4.8% |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis/Osteoarthritis | 2 | 2 inpatient or HOP/carrier claims | 21.9% | 28.0% | 30.0% |

| Stroke | 1 | 1 inpatient or 2 HOP/carrier claims | 8.0% | 10.7% | 11.3% |

Source: Chronic Condition Warehouse, http://www.ccwdata.org/chronic-conditions/index.htm for the diagnostic codes assigned to each health condition. For HIV/AIDS which is not coded by CCW, we use ICD-9 DX codes 042XX 043XX 044XX 07953 V08XX; these are taken from CMS’s HCC risk model.

A key variable in our analysis is an individual’s total drug bill (TDB) in her chosen stand-alone Part D plan, defined as the annual sum of pharmacy prices of her prescriptions (her medicine cabinet) reported in her Part D claims files.8 Figure 1 gives the cumulative distribution functions of 2006, 2007, and 2008 total drug bills in our final working samples. These distributions are virtually identical, even though the bills are in nominal dollars, indicating that trends in pharmacy benefit management, changes in drug prices and the patent status of some major branded drugs, and changes in the drug needs of the population in stand-alone PDP coverage have effectively cancelled each other out. Also shown in Figure 1 is CMS’s forecast in 2002 of the distribution of 2006 drug bills, based on the 1998 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, which was used by government agencies and some insurers to predict the costs of providing Part D coverage. In retrospect, this forecast substantially over-estimated the mean drug bill and the dispersion of drug bills. The 2002 forecast had a mean of $2732 (s.d. $3395) compared with a mean of $2050 (s.d. $2146) in the 2006 realization. The descriptive statistics for the realized total drug bills in 2006, 2007, and 2008 are reported in Table 1. The table also shows the correlations of drug bills across years, which are fairly high (above to 75% for adjacent years). We return to these numbers when we describe enrollment choices in section 3 below.

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution functions of annual total drug bills

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for observed total drug bills

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | $2050 | $2258 | $2299 |

| Median | $1679 | $1831 | $1811 |

| Percent Zero | 6.1% | 3.7% | 3.5% |

| s.d. | $2146 | $2551 | $2906 |

|

| |||

| Correlations | |||

| TDB 2006 | 0.768 | 0.631 | |

| TDB 2007 | 0.797 | ||

Note: All figures are in current dollars.

2.2 From prescription drug claims data to simulated plan choices

For each beneficiary in our working samples in each of the years 2006, 2007, and 2008, we observe a complete record of each prescription filled and submitted to Medicare for reimbursement. Each claim includes detailed information on the pharmacy price9 and copayment for the particular drug and quantity dispensed, days supplied, on which tier the insurance plan classifies the drug, the benefit phase associated with each claim, the National Drug Classification (NDC) code of the drug, and the prescription’s date. We also observe for each beneficiary the critical determinant of benefit phase in Part D plans, the cumulative true out-of-pocket (TrOOP) cost in a benefit year, defined by CMS as enrollee out-of-pocket payments for drugs contained in a plan’s formulary (including drugs covered on appeal).

We assume that consumers care about annual out-of-pocket (AOOP) costs, which we define as annual TrOOP costs plus over-the-counter and off-formulary prescription drug purchases that do not generate claims, and about annual total drug-related expenditures, the sum of annual plan premiums and AOOP costs, which we term consumer inclusive cost (CIC).10 However, we have no data on drug purchases that do not generate claims. Therefore, for chosen plans we approximate AOOP costs by annual TrOOP costs and CIC (the sum of premium and AOOP) by the sum of premium and TrOOP costs. For people who purchase drugs that do not generate claims, these approximations will understate total drug-related expenditures and miss some medications.

Our study of choice behavior starts from a simulation of each beneficiary’s annual TrOOP and AOOP costs, and CIC, for each available stand-alone Part D plan in his region. There are two main parts to this simulation: (1) determining the formulary and benefit design (FBD) for each plan, and (2) running each beneficiary through these FBDs to estimate annual TrOOP and AOOP costs, and CIC, based on each plan’s rules and copayment provisions.

2.2.1 Construction of empirical FBDs

There are five types of Part D stand-alone PDPs approved by CMS: Standard, Actuarially Equivalent, Basic Alternative, Generic Extended, and Full Extended. A Standard plan has an administratively specified benefit schedule with four phases determined by an annual deductible, an initial coverage phase with a 25 percent copayment, a gap or doughnut hole with no coverage when TrOOP is between the level determined by an initial coverage limit (ICL) and a catastrophic coverage threshold (CCT), and a catastrophic phase above the CCT with a 5 percent (or equivalent) copayment. Table 2 gives the Standard plan benefit parameters for each year in our data, and the drug price index used by CMS to adjust these parameters each year. Actuarially Equivalent plans differ from the Standard plan only by substituting copayment tiers for copayment percentages, keeping benefit generosity the same on average. Basic Alternative plans are like Actuarially Equivalent plans, but eliminate the deductible phase, and are required to be at least as generous as the Standard plan. Enhanced plans resemble Basic Alternative plans, but add gap coverage at the equivalent of a 25 percent copayment rate, for generic drugs only in Generic Enhanced plans, and for all formulary drugs in Full Enhanced plans. Because Enhanced plans reduce OOP costs through the gap phase, higher drug bills are required to reach the CCT.11

Table 2.

Characteristics of Medicare Part D plans

Characteristics fixed by plan

|

Characteristics specific to drugs within a plan

|

| Characteristics established by Medicare standard plan parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| Deductible | $250 | $265 | $275 |

| TrOOP at Initial Coverage Limit (ICL) | $1,750 | $1,866 | $1,951 |

| Initial Coverage Limit | $2,250 | $2,400 | $2,510 |

| TrOOP limit for catastrophic coverage | $3,600 | $3,850 | $4050 |

| Drug bill for catastrophic coverage | $5,100 | $5451.25 | $5,726.75 |

| Copayment, Deductible < Bill < ICL | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| Copayment, catastrophic coverage: | |||

| Generic or Preferred Multi-Source | $2.00 | $2.15 | $2.25 |

| Other Drugs | $5.00 | $5.35 | $5.60 |

| Drug Cost Index | 1.000 | 1.067 | 1.116 |

The Part D data identify plan types, but CMS confidentiality rules encrypt the identities of individual plans. Consequently, we cannot assign published plan formularies from public CMS records to these encrypted identifiers, and thus are unable to calculate from actual formularies the benefits and out-of-pocket costs for plans available but not chosen.12 As a substitute, we construct an empirical formulary for each insurance plan that is the union of all the NDC codes of claims of enrollees in our Part D working sample who are in plans with the same formulary identifier in a specified year. Appendix B details this construction, and its limitations.

Our data give, for each drug appearing in the empirical formulary of a plan, its branded/generic/preferred status classification, tier classification (with processing of off-tier claims detailed in Appendix B), and pharmacy price (total cost). We estimate a benefit design for each plan based on drug classification, phase-dependent empirical tier copayment rate, days supplied, and the type of pharmacy that fills the prescription. At the end of this construction, we have an empirical FBD for each plan and year that we use to estimate the annual TrOOP cost of any specified list of prescriptions supplied under that plan.

2.2.2 Simulation of TrOOP and AOOP costs, and CIC, for alternative plans

Each person in our working sample is characterized by an observed medicine cabinet (MC) – the list of prescriptions a person has filled over a year – which we obtain from her claims records. As noted earlier, observed medicine cabinets exclude over-the-counter and off-formulary prescription drugs that do not generate claims. In making plan choices, a person may consider their medicine cabinet in the previous year and other “what if” medicine cabinets that they might require contingent on future health conditions. To study the quality of plan choices, we impute for various medicine cabinets “what if” AOOP costs in the available plans, both chosen and alternative. To do this, we plug each medicine cabinet into the empirical FBD for each available plan to estimate TrOOP costs, add in the pharmacy price of drugs in the medicine cabinet that are not in the plan’s formulary to estimate AOOP costs, and finally add in annual premiums to estimate CIC.

Several important behavioral assumptions enter this estimation, and affect the interpretation of choice quality. First, we assume that over-the-counter and off-formulary drug purchases in a chosen plan continue to be made under any alternative plan, so that in plan comparisons these purchases wash out. However, it is possible that some off-formulary drug purchases under a person’s chosen plan will be covered at lower net out-of-pocket cost in an alternative plan, in which case we overstate the net AOOP difference between the alternative and chosen plan. Second, we make the no-substitution assumption that the medicine cabinet will not be modified under alternative plans, so that exactly the same drugs and dosages are used. If instead the person adjusts their medicine cabinet to the alternative plan, substituting therapeutically equivalent drugs and/or adjusting dosages to obtain lower copayments, then our estimation will again overstate the net AOOP difference between the alternative and chosen plans. Then, under these behavioral assumptions, our analysis may conclude incorrectly that a chosen plan is superior to an alternative plan, but should never conclude incorrectly that a chosen plan is inferior to an alternative plan.

To test the no substitution assumption, we also consider a therapeutic substitution assumption. Under that alternative, if a medicine cabinet contains a drug that is not in the formulary of one of the available alternative plans, this drug is replaced in all plans, including the chosen plan, by a therapeutic equivalent with the lowest copayment. In general, this may understate actual AOOP in the chosen plan, but the estimation allows an “apples-to-apples” comparison of plan costs. However, it is possible that if a person prefers a specific drug to a lower cost therapeutic equivalent in their chosen plan, and another plan does not have this specific drug in their formulary but has a lower cost therapeutic equivalent, our analysis could incorrectly conclude that the chosen plan is inferior to this alternative plan. If medicine cabinets are predetermined by patient and provider preferences, then the no substitution assumption is the most appropriate. However, if medicine cabinets are endogenously determined by patients and providers interacting with pharmacy benefit managers and insurers, then the therapeutic substitution assumption is more appropriate. Details of the estimation of TrOOP, AOOP, and CIC for alternative plans and medicine cabinets are given in Appendix C.

2.2.3 Validity of the simulation

The simulation’s internal validity is tested by examining simulated minus actual AOOP spending, with no substitution in the simulation, for each beneficiary in their chosen plan. Actual AOOP is defined here as the sum of patient payments not reimbursed by a third party, all qualified third party payments, and patient liability reductions due to coordination of benefits from other payers. The median difference in simulated minus actual AOOP is $0, the mean difference is −$13.62, and the correlation coefficient exceeds 0.99. This compares favorably to a similar simulation check presented in Ketcham et al. (2012). Figure 2 displays the distribution of this difference; for more than 99.6 percent of the beneficiaries, the difference is less than $500 in absolute value. The small size of these differences for most beneficiaries suggests that the simulation performs reasonably well and is likely accurate for predicting AOOP spending in the plans not chosen.

Figure 2.

Distribution of differences between actual and simulated OOP costs

However, there are still some outliers for whom the difference between simulated and actual AOOP is large. Figure 3 plots the empirical mean of simulated AOOP cost in 2007 against overall drug bill for consumers on various plans, and compares this with the designed standard plan benefit schedule. The figure indicates that the simulated benefits for Standard and Actuarially Equivalent plans conform well to the designed schedule over the phases where benefits are paid, but give somewhat higher AOOP costs when drug bills are in the gap. This may be a statistical artifact, or may be evidence that consumers are being surcharged on drugs purchased in the gap where there is no coverage. The AOOP costs for plans with brand and generic gap coverage show the expected reduction of AOOP costs in the gap phase. The relatively higher AOOP costs for plans covering only generics in the gap phase may suggest that branded drugs are the primary cost driver at that level of spending. For comparability of chosen and non-chosen plans, we use hereafter annual imputed adjusted AOOP costs of a medicine cabinet, with or without therapeutic substitution, rather than a mix of observed AOOP costs for the chosen plan and imputed AOOP costs for alternative plans.

Figure 3.

Empirical means of 2007 simulated out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for alternative plan types and the Part D standard plan designed benefit schedule, conditioned on annual total drug bill

3. Enrollment choices

We begin our analysis of the administrative data on Medicare Part D by looking at the enrollment decision; this complements earlier research that used survey data such as Winter et al. (2006) and Heiss et al. (2006, 2009).

The Part D program is heavily subsidized, with insurers reimbursed from government general revenues for about 75 percent of overhead and benefits paid out, with fairly tightly regulated formulary and benefit design and competitively determined premiums. As a result, the program is first-year actuarially favorable for most eligible people, even before considering the value of reducing risk and the option value of avoiding delayed enrollment penalties if a Part D plan becomes attractive in the future (Winter et al., 2006).

The marketing and information provided on Part D policies by insurers and by CMS focus on the expected benefits rather than on risk reduction. In particular, the CMS Plan Finder invites users to list current drugs, and then provides a list of available plans ranked by out-of-pocket cost if the current drug use continues through the coming year. While consumers could in principle use Plan Finder on a “what if” basis by introducing counterfactual drugs and dosages, it would be cumbersome to do this and combine the results into an analysis of expected plan benefits and costs. No direct information is provided on the likelihood that the person will have different drug needs, the ability of plans to meet these needs, and the reduction in risk offered by plans with more generous coverage. As a result, consumers are nudged toward lowest cost plans under the static forecast that current drug use will continue without change, rather than being nudged toward overall risk management.

This said, the set of current drugs taken and the total drug bills (TDB) are good predictors of one-year-ahead drug needs. Table 1 above shows that the pairwise correlations of TDB between adjacent years over the period 2006, 2007, and 2008 are all above 0.75; the table also provides descriptive statistics for each year. These statistics suggest that persons with even modest drug bills can expect to be ahead of the game by enrolling, even if they are not risk-adverse or concerned about the late enrollment penalty and future options. As noted above, the cumulative distribution functions of 2006, 2007, and 2008 total drug bills for the populations that had full-year enrollment in a stand-alone prescription drug plan in all three years, depicted in Figure 1, are virtually identical in 2007 and 2008, and only slightly shifted downward in 2006, even though bills are in nominal rather than real terms. This indicates that adjustments in pharmacy benefit management have essentially offset rising drug prices, changing patent status of some major branded drugs, and changing risk characteristics of the population that selects stand-alone PDP coverage. Also plotted in Figure 1 is the 2008 density, scaled, which shows a piling up of people at the beginning of the gap where increased copayments reduce incremental demand for drugs.13

Figure 4 gives the cumulative distribution functions for 2008 total drug bills, conditioned on the 2007 drug bill percentiles. As the relatively high inter-year correlation implies, these CDF are relatively tightly distributed around the 2007 levels, but with some regression to the mean. However, they have relatively thick right tails. Figure 5 plots the conditional mean of the 2008 total drug bill, and the contour giving the approximate 95th percentile, against the 2007 total drug bill. The scales are logarithmic, so that this graph shows substantial risk of large increases in drug bills over the previous year. Below a 2007 drug bill of $2317 (the 71st percentile), the 2008 conditional mean exceeds the 2007 drug bill, and above this level, the reverse is true, reflecting regression to the mean.

Figure 4.

Cumulative distribution functions of 2008 total drug bill conditioned on 2007 total drug bill percentile

Figure 5.

Mean and 95th percentile of 2008 total drug bill, conditioned on 2007 total drug bill

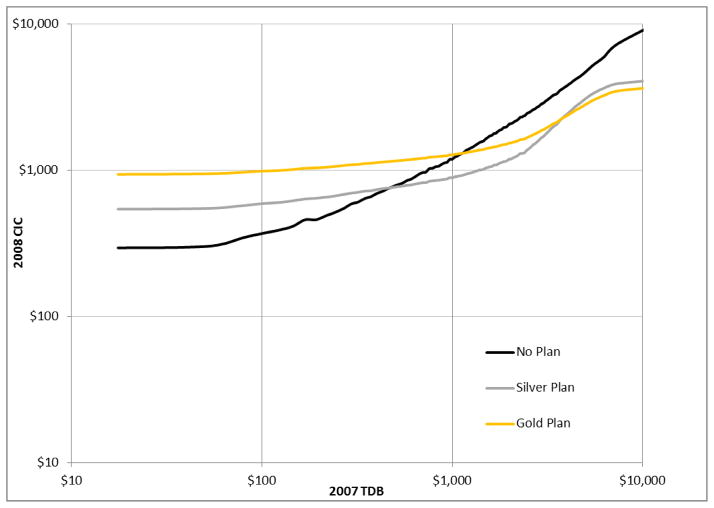

A myopic consumer who considers only first-year benefits from a Part D plan and is risk neutral should enroll if expected benefits received exceed the premium. Consider a Part D standard or equivalent plan in 2008, which had a typical premium of $30 per month. Figure 6 gives the probability, conditioned on 2007 total drug bill, that an enrollee in the standard plan will be ahead of the game in the first year, with benefits exceeding the annual premium. For 2007 drug bills above $690, this probability exceeds 50 percent. The probability peaks at a 2007 drug bill of about $5000, and thereafter declines slightly, apparently due to elevated mortality risk for people with very high drug bills. Figure 7 gives the expected cost conditioned on the 2007 total drug bill for non-enrollment, enrollment in a Silver (i.e., standard or equivalent) plan, and enrollment in a Gold (i.e., generic drug coverage in the gap) plan with a premium at the national average of $63.34 per month. These curves assume that 50 percent of drug costs in the gap are generic. At a 2007 drug bill of $470, corresponding to a 2008 expected drug bill of $760, enrollment in a Silver plan breaks even with non-enrollment in terms of expected cost. Then, if risk aversion and an option value for avoiding a late enrollment penalty in future years are not considerations, 19.5 percent of the eligible population is best off not enrolling. At a drug bill of $3,744 in 2007, corresponding to an expected drug bill of $3,570 in 2008, the Silver and Gold plans break even in terms of expected cost. Then, the 9.5 percent of the eligible population with the highest 2007 drug bills is best off with a Gold plan. Moreover, if first-year payoff is the only criterion and risk is not a consideration, about 12 percent of those enrolling in Part D plans would choose a Gold plan.

Figure 6.

Probability that standard plan enrollment in 2008 at a $30 per month premium gives lower consumer cost than non-enrollment, conditioned on total drug bill in 2007 (log scale)

Figure 7.

2008 expected consumer inclusive cost (OOP plus premium) of “No Plan”, “Silver” (Standard) plan, and “Gold” (gap generic coverage) plan choices, given 2007 total drug bill

In an earlier analysis of Part D enrollment choices using a national sample of about 2,500 eligible people, Heiss, McFadden, and Winter (2009) found that 23.8 percent of those not automatically enrolled in Part D through retiree plans or Medicaid chose to not enroll. CMS tabulations from the denominator file show that 15.1 percent of the eligible population was without drug insurance of some creditable14 form in 2008 – this will translate into a higher percentage of those who are active deciders with a personal choice of whether to enroll and if so what plan to choose (see Table 3).15 While these rates bracket the 19.5 percent that the simple analysis above would suggest if consumers are myopic and risk-neutral, the actual pattern of non-enrollment was much more random, including many who left money on the table in the first year as the result of their enrollment choice. The earlier finding was that non-enrollment was concentrated among those with low but above-poverty incomes, low education, and relatively low prior drug use. The earlier analysis also found that when the option value of Part D insurance without a late enrollment penalty is taken into account, only a few percent of very old people with little drug use should rationally choose to not insure. Then, the observed rates of non-enrollment indicate that myopia and inattention are significant, and are reducing prescription drug insurance participation rates below levels that are optimal for individuals.

Table 3.

Medicare Part D enrollment in December, 2006–2008 (Denominator File)

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 65+ | Pct | Total | 65+ | Pct | Total | 65+ | Pct | |

| Total | 43,338,571 | 36,316,594 | 44,263,111 | 36,965,846 | 45,411,883 | 37,896,079 | |||

| No Part D, Retiree Drug Subsidy, or Creditable Coverage | 7,801,239 | 6,516,882 | 17.9% | 7,053,805 | 5,799,802 | 15.7% | 6,980,480 | 5,726,326 | 15.1% |

| Part D Enrolled | |||||||||

| Total | 22,854,973 | 18,368,305 | 50.6% | 24,477,276 | 19676031 | 53.2% | 25844675 | 20,790,368 | 54.9% |

| With Creditable Coverage | 2,663,377 | 2,172,276 | 6.0% | 2,922,694 | 2,406,994 | 6.5% | 2,174,420 | 1,831,963 | 4.8% |

| Without Creditable Coverage | 20,191,596 | 16,196,029 | 44.6% | 21,554,582 | 17,269,037 | 46.7% | 23,670,255 | 18,958,405 | 50.0% |

| Retiree Drug Subsidy | |||||||||

| Total | 6,838,613 | 6,552,456 | 18.0% | 7,009,702 | 6,715,950 | 18.2% | 6,655,834 | 6,380,143 | 16.8% |

| With Creditable Coverage | 676,496 | 637,207 | 1.8% | 703,149 | 659,076 | 1.8% | 624,879 | 584,305 | 1.5% |

| Without Creditable Coverage | 6,162,117 | 5,915,249 | 16.3% | 6,306,553 | 6,056,874 | 16.4% | 6,030,955 | 5,795,838 | 15.3% |

| Creditable Coverage (No Part D or Retiree Drug Subsidy) | 5,843,746 | 4,878,951 | 13.4% | 5,722,328 | 4,774,063 | 12.9% | 5,930,894 | 4,999,242 | 13.2% |

| Creditable Coverage Without Regard to Part D or Retiree Drug Subsidy | 9,183,619 | 7688434 | 21.2% | 9348171 | 7840133 | 21.2% | 8730193 | 7415510 | 19.6% |

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid 2007–2009 Statistical Supplements, Table 14.4

We summarize Part D plan choice in our 20 percent sample of all people eligible for Medicare Part D in Table 4. Gold plans (combined with the relatively unimportant Platinum plans with full gap coverage) have a 8.1 percent share of those enrolled in Part D plans in 2007.16 Thus, Gold plans appear to be undersubscribed relative to their first-year actuarial value. The complexity of the valuation of Silver and Gold plans, the availability of plans at national average premiums, consumer errors in assessing the actuarial value of gap coverage and focus on premium costs over potential benefits, and our assumption on the share of generics in gap purchases are factors that may contribute to this difference in predicted and actual market share. What the numbers indicate is that risk aversion is apparently not strong enough to offset the (perceived) disadvantageous loading of extended benefits.

Table 4.

Counts by Part D enrollment status of 20% sample and working sample

| 2006 | % | 2007 | % | 2008 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. 20% Sample: Part D Enrollment Status in December | ||||||

| Not enrolled in Part D with creditable coverage | 1,295,192 | 14.3 | 1,292,191 | 13.9 | 1,312,470 | 13.8 |

| Not enrolled in Part D without creditable coverage | 2,769,583 | 30.5 | 2,685,661 | 28.9 | 2,630,485 | 27.6 |

| Enrolled in Medicare Advantage plan | 1,311,554 | 14.4 | 1,507,154 | 16.2 | 1,724,249 | 18.1 |

| Enrolled in employer-provided retiree plan (starting Jan 2007) | NA | NA | 25,024 | 0.3 | 25,349 | 0.3 |

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone basic (silver) plan | 3,121,961 | 34.4 | 3,136,343 | 33.7 | 3,223,848 | 33.8 |

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone enhanced (gold) plan | 93,125 | 1.0 | 253,080 | 2.7 | 236,295 | 2.5 |

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone full gap coverage (platinum) | 95,856 | 1.1 | 23,468 | 0.3 | 75 | 0.0 |

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone plan for which coverage could not be determined | 24,410 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 |

| NEC | 374,659 | 4.1 | 376,926 | 4.1 | 377,837 | 4.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Total, 20% Sample | 9,086,340 | 100 | 9,299,848 | 100 | 9,530,609 | 100 |

|

| ||||||

| Panel B. Working Sample Enrollment throughout year | ||||||

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone basic (silver) plan | 1,106,503 | 89.8 | 1,062,131 | 84.1 | 1,113,201 | 86.7 |

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone enhanced (gold) plan | 81,748 | 6.6 | 182,897 | 14.5 | 171,110 | 13.3 |

| Enrolled in Part D stand-alone full gap coverage (platinum) | 44,380 | 3.6 | 18,280 | 1.4 | 45 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Total, Working Sample | 1,232,631 | 100 | 1,263,308 | 100 | 1,138,105 | 100 |

Note: The top panel displays the enrollment status in December of the particular year, providing a snapshot for all beneficiaries on the denominator file. The bottom panel tabulates the type of gap coverage for our working sample, which is constructed as shown in Table 3. Since our sample is restricted to people enrolled in the same PDP plan throughout the year, these coverage counts remain constant throughout the year.

The analysis above did not condition on the demographic variables available in claims data, gender and age. We find that drug use does vary with these variables, but that conditioned on prior drug use, they have little explanatory power. Thus, further conditioning on these demographic variables does not alter our general conclusions on enrollment.

4. Models of plan choice behavior

In this section, we develop an analytic framework for assessing the quality of Part D plan choices. Plan choices are ex ante, made during the open-enrollment period at the end of each year for the plan that will be in place during the coming year, before actual health conditions and drug needs in the coming year are realized. Evaluations of the quality of plan choice should be correspondingly ex ante, based on expected utility in the year ahead given current information, the decision criterion for rational individuals facing uncertain prospects. We apply this framework to evaluate peoples’ plan choices for 2007 made at the end of 2006, and choices for 2008 made at the end of 2007.

In overview, we ask whether people, using the information they arguably had available at the time of their actual plan choice, could have achieved higher expected utility than they did. We make these assessments by comparing the expected utility of actual choices with the expected utility from benchmark decision rules. A leading benchmark, and the focus of much of our empirical analysis, is the recommendation of the CMS Plan Finder, which ranks the cost of plans in the coming year when given a person’s medicine cabinet for the past year. This decision rule is available to any senior who can access the Medicare website, personally or through a helper. Another benchmark we use in order to make comparisons to the earlier literature is the infeasible rule that maximizes utility under perfect foresight on future health conditions and drug needs. In section 4.1, we give the foundation for the expected utility criterion and provide some preliminary evidence on the elements that enter utility. In section 4.2, we discuss notions of ex ante and ex post optimization errors, our framework for ex ante assessment of the quality of plan choice, and the benchmark decision rules we consider. We present our results on the quality of Part D plan choices in Section 4.3.

4.1 Rational expectations and decisions

We describe a model of expected utility of plans in the Medicare Part D market that allows for uncertainty about future drug needs, and alternative protocols for expectation formation. This model cannot be made operational without a number of assumptions, but it nevertheless provides a framework for forward-looking choices that is consistent with the economic standard for rational choice.

We make the reasonable assumption that at the time of their plan choice at the end of a year for the upcoming year, consumers know the drugs they have used over the current year, their health conditions, and their realized drug bill for the year, and they can calculate from public information (e.g., the CMS Plan finder) their projected CIC for each plan alternative they face and each medicine cabinet they may need. Since the open enrollment periods for 2007 and 2008 were mid-November to mid-December in the preceding year, this is a good but not perfect assumption, as end-of-year events that appear in our information measures may not be predictable by the individual, and no public source including Plan Finder makes it easy to carry through a sophisticated forecast of the likelihood and consequences of changes in health and drug needs.

We assume in practice that the information each consumer has in year t-1, denoted Xt-1, includes their age and gender, their medicine cabinet (MCt-1, a high-dimensional vector that describes all the consumer’s prescription claims over the year and includes information on the drug, dosage, and number of days supplied for each prescription), their end-of-year health status (based on the CMS Chronic Condition Warehouse (CCW) inventory of chronic health conditions), their risk score for expected drug costs (based on the Hierarchical Condition Code (HCC) used by CMS for risk adjustment), their total drug bill, their Part D plan (if any), and the annual premium and realized AOOP cost (and hence realized CIC) under this plan. Of course, it is possible that people cannot retrieve all this information, or that they do so with error. It is also possible that people have additional (private) information on their circumstances, in which case decisions based only on the information above are “boundedly” rational.

Each consumer is assumed to have sufficient information, from the CMS Plan Finder or otherwise, to determine the formulary and benefit design mapping for each Plan k available in year t in her region, which we denote AOOP = FBD(MC,k, t), that gives the AOOP for any given medicine cabinet MC.17 She is also assumed to form, using information obtained from peers or otherwise, expectations of future drug use, i.e., a personal conditional density f(MC | k,Xt-1) of year t medicine cabinets given end-of-year t-1 information. From this, we assume that the consumer can deduce the conditional distribution of AOOP cost in period t given covariates Xt-1 and plan k, as well as its conditional cumulant generating function m, mean MAOOP, and variance VAOOP:

For a consumer with rational expectations, the density f will be statistically accurate. Consumers with less than fully rational expectations may have densities f that are not fully accurate because they ignore available conditioning information, or because their beliefs are not realistic.

We assume that the preferences of consumers can be approximated by CARA utility functions U = (1 − exp(−α(w − Premium − AOOP)))/α, where α > 0 is a coefficient of risk aversion that approaches zero in the limiting case of risk neutrality, w is “permanent income” that can vary across individuals due to variations in wealth and in other risky opportunities, Premium is the annual Part D premium, and AOOP is the (uncertain) annual out-of-pocket cost. Expected utility of plan k in period t given the information Xt-1 available at the time of plan choice is then

When α is small, m(α | k,Xt-1)/α ≈ MAOOP(k, Xt-1) + αVAOOP(k,Xt-1)/2 is a certainty-equivalent expected AOOP. Le ECICkt = Premiumkt + MAOOP(k,Xt-1) denote expected CIC. Then expected utility is a decreasing function of certainty-equivalent expected CIC: ECICkt + αVAOOP(k,Xt-1)/2. Plan choice to minimize this sum in k is then a benchmark for rational choice, and certainty-equivalent expected CIC is a metric for losses when choice behavior is not fully rational. Choice will fail to be fully rational for a consumer with small α if (1) Xt-1 does not include all available relevant information, (2) information processing to calculate MAOOP(k,Xt-1) and VAOOP(k,Xt-1) is statistically inaccurate, or (3) plan choice fails to minimize certainty-equivalent expected CIC. In addition, we may fail to recognize choice as rational if Xt-1 contains private information available to the decision-maker that we do not observe. In general it will be difficult to identify which of these conditions is responsible for rationality failures.

This utility formulation leaves out the possibility that AOOP cost risk is correlated with other risks entering w so that they must be evaluated jointly. It ignores plan attributes such as service quality and pharmacy store convenience that may enter preferences. It also treats rational plan choice as a one-year decision that does not require intertemporal optimization of a discounted stream of utilities. Since the consumer is free to re-optimize in each annual open enrollment period, the conditions for separability of the intertemporal problem into a series of one-year decisions are largely met. However, factors that could reintroduce an intertemporal element would be switching costs between plans, leading consumers to prefer plans with good expected long-term performance even if they are not first-year optimal, or intertemporally non-separable preferences in which habit and inertia enter the determination of consumer well-being.

To test our expected utility formulation, we estimate multinomial logit models of plan choice with the certainty-equivalent expected CIC components as explanatory variables: Premium, MAOOP, ECIC = Premium + MAOOP, and VAOOP. The results are given in Table 5 for each of the plan years 2007 and 2008, for two different constructions of the expectations MAOOP and VAOOP, the first based on Plan Finder, and the second based on our approximation to rational expectations. The details of these expectations constructions are given in Section 4.2. We are unable to include in these models measures of plan quality, such as telephone response and appeal resolution times. These are reported in CMS public data on plans, but are not provided for the encrypted plans in our sample of Part D claims. We do include dummy variables to capture brand and quality differences that vary by insurer; these have little effect on the coefficients of the variables of interest. In Table 5, models (1) for 2007 and (4) for 2008 correspond to the assumptions that people are risk neutral and that they weigh premiums and expected out-of-pocket prescription costs the same. In both years and with both expectations models, the effect of expected CIC is highly significant and of expected sign, but the share of likelihood explained by the models (pseudo R2) is low and a $10 per month difference in expected CIC between plans would induce only about 56% of people to choose the less expensive plan. Thus, sensitivity to cost appears to be low, and choices that fail to achieve minimum expected cost are common. The rational expectations construction explains choice a little better than the Plan Finder construction. The larger magnitude of the coefficient on MAOOP in the rational construction is consistent with the hypothesis that the Plan Finder construction less accurately approximates the quantity that drives choice.

Table 5.

Multinomial logit models predicting Medicare Part D plan choice in 2007 and 2008

| 2007

|

2008

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Static (Plan finder) decision rule | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ECIC | −1.891E-03 | −1.024E-03 | ||||

| 4.550E-06 | 3.560E-06 | |||||

| Premium | −2.140E-03 | -2.140E-03 | −1.370E-03 | −1.537E-03 | ||

| 6.060E-06 | 6.010E-06 | 4.590E-06 | 4.800E-06 | |||

| MAOOP | −1.620E-03 | −1.617E-03 | −4.471E-04 | −1.172E-03 | ||

| 6.130E-06 | 6.170E-06 | 5.570E-06 | 6.630E-06 | |||

| VAOOP | −1.310E-08 | 3.810E-06 | ||||

| 2.650E-09 | 1.890E-08 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 3.185E-01 | 3.191E-01 | 3.191E-01 | 2.692E-01 | 2.711E-01 | 2.749E-01 |

| α | 2.746E-05 | −6.503E-03 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Rational decision rule | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ECIC | −2.398E-03 | −1.760E-03 | ||||

| 5.620E-06 | 4.580E-06 | |||||

| Premium | −2.500E-03 | −2.502E-03 | −1.789E-03 | −2.036E-03 | ||

| 6.490E-06 | 6.490E-06 | 4.950E-06 | 5.270E-06 | |||

| MAOOP | −2.235E-03 | −2.229E-03 | −1.679E-03 | −2.108E-03 | ||

| 7.440E-06 | 7.450E-06 | 6.700E-06 | 6.930E-06 | |||

| VAOOP | −7.000E-08 | 3.380E-06 | ||||

| 2.870E-08 | 1.610E-08 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 3.209E-01 | 3.211E-01 | 3.211E-01 | 2.766E-01 | 2.767E-01 | 2.809E-01 |

| α | 6.280E-05 | −3.206E-03 | ||||

Notes: Standard errors in shaded rows. ECIC: expected value of consumer inclusive cost (the sum of premium and MAOOP); MAOOP: conditional mean of out-of-pocket cost; VAOOP: conditional variance of out-of-pocket cost. The models also include 80 dummy variables for the insurers; these coefficients are not reported. The decision rules are described in Section 4.2.

Models (2) and (4) reported in Table 5 allow different weightings for premiums and expected out-of-pocket prescription costs. With the rational decision rule, the two components have nearly the same weight, with slightly more sensitivity to Premium than to MAOOP. With the Plan Finder decision rule, the difference is pronounced. Thus, there is evidence that “a dollar is not a dollar” for these two cost components. These weightings are consistent with a widely observed behavioral phenomenon that people discount future and ambiguous costs relative to certain cost commitments made in the present. These results are also consistent with the finding by Abaluck and Gruber (2011) that plan choices in Medicare Part D react more strongly to plan premiums than to other relevant features such as expected out-of-pocket cost.

Models (3) and (6) reported in Table 5 include VAOOP, and can be used to estimate the risk-aversion parameter α. The two years give conflicting results, with 2007 showing modest risk aversion18, and 2008 showing risk preference. We compared the expected utility of a standard (silver) plan with that of a gold plan with generic gap coverage, and find in 2007 that the average annual premium difference that makes a risk-neutral person indifferent between the two is $100.38, and that which makes a person with the risk aversion parameter estimated with the rational decision rule in Model (3) indifferent between the two is $96.25.19 Thus, risk aversion in 2007 is not economically significant. We leave for future research the mystery of apparent risk preference in 2008, but note that the risk associated with Part D plans is quite difficult to determine, and consumers may be responding to plan features correlated with actual risk rather than to the risk itself.

We conclude from our preliminary analysis that expected CIC is a reasonable criterion for assessing the quality of plan choice, that a source of failures to minimize expected CIC may be that consumers place a higher weight on premiums than on MAOOP, and that risk preferences are not a consistent source of failures to minimize expected CIC.

4.2 Ex post and ex ante optimization errors

We take an ex ante approach to evaluation of the quality of Part D plan choices, comparing the expected performance of actual choices and various benchmark decision rules, conditioned on the information that people had access to at the time of choice. Based on our preliminary analysis in section 4.1 of the elements of rational choice and apparent behavioral determinants of choice, we take as metrics of performance relative to each benchmark the averages over our working sample of the conditional probabilities that actual choice had higher expected consumer inclusive cost (ECIC), and of the conditional expected excess cost, the difference in ECIC between these decision rules. Our finding of no consistent, significant risk aversion is the justification for our use of ECIC rather than a certainty-equivalent ECIC that would come more generally out of our CARA utility function framework. The probability of higher ECIC from actual choice than from a benchmark gives information on frequency of failures to attain the benchmark rule performance, while expected excess cost gives information on the economic significance of these failures.

Let CICat denote realized consumer inclusive cost over year t from the actual plan choice made at the end of year t-1 (“plan a”), and CICbt realized consumer inclusive cost over the same year from a benchmark choice (“plan b”). We reconstruct these quantities without or with therapeutic substitution of generic drugs for uncovered branded drugs. The realized excess expenditure CICat – CICbt is an ex post measure of regret with respect to benchmark plan b experienced by the individual. This quantity may influence the person’s decision-making attention and focus at the end of year t for its plan choice in year t+1, but unless the individual has perfect foresight, it is unknown at the end of year t-1 when a plan is chosen for year t. Regret may be wistful (“If I had known then what I know now …”) or feasible (“If I had only checked Plan Finder …”); the difference is whether benchmark rule b could have been implemented with information available at the time of choice. Regret can be averaged over the working sample and interpreted as an ex post measure of the quality of plan choice relative to a wistful or feasible benchmark.

Our ex ante performance measures are designed to depend only on information available at the time a plan is chosen, so that against a feasible benchmark rule, they provide a practical assessment of opportunities missed. They start from the probability of overspending, and expected overspending, conditioned on the information Xt-1 available to an individual at the time of plan t choice. These quantities are then averaged over the information sets in the population:

The final equalities, showing that these measures are simply unconditional expectations over the population, are applications of the law of iterated expectations. We estimate these expectations by replacing them with their empirical equivalents, averages over the working sample.20

With these definitions, we can clarify the relationship between the ex ante performance measures for consumer decision making that we adopt, and an ex post measure employed previously by Ketcham et al. (2012) and emphasized by Zhang and Zhou (2012) that calculates average regret relative to the benchmark of perfect foresight. The distinction between ex ante and ex post performance metrics comes from whether or not the benchmark is feasible, since for a given benchmark the estimate of expected excess spending in the ex ante calculation is identical to the average of regret in the ex post calculation. The ex post comparison with the perfect foresight rule is potentially quite misleading, as even a consumer who makes a fully rational expected-utility maximizing choice can have large wistful regret relative to the perfect foresight benchmark when uncertainty is high. However, differences in average ex post excess spending, relative to the perfect foresight benchmark, between actual choice and a feasible benchmark choice will coincide with ex ante average excess spending. (This result depends on linearity, and does not hold for calculations of shares with excess spending.)

To implement our performance calculations, we consider the (infeasible) perfect foresight benchmark, and four feasible benchmarks: the CMS Plan Finder rule that picks out the plan with the lowest CIC given the previous year’s medicine cabinet, a random benchmark that picks from available plans at random, a minimum premium benchmark that selects a plans that has the lowest annual premium, and a “rational” benchmark that picks a plan to minimize ECIC, conditioned on information available on health and drug needs at the time of plan choice. We implement these benchmark rules as follows:21

Perfect foresight: In year t-1, the consumer forecasts exactly her drug needs in year t. This rule is infeasible except under unrealistic information conditions, but it is an ingredient in ex post performance measures and should give an upper bound for expected excess spending.

Plan Finder: The consumer chooses the plan that minimizes CIC, given the realized drug cabinet in year t-1. In effect, drug use in year t is expected to be the same as in year t-1. Let CICSkt = FBD(MCt-1, k, t) denote this static expected CIC, and call it the Plan Finder Predicted CIC (PFPCIC). Brand and generic substitutions are made when the CIC simulations are made with therapeutic substitution. Actual choice should have zero excess spending when consumers follow the recommendation of the CMS Plan Finder, except for differences in AOOP costs resulting from pharmacy choices, and differences between actual and simulated empirical formularies (see Appendix C).

Random: A plan is drawn at random from those available, in effect all plans are treated as if they have the same expected CIC.

Minimum premium: A related decision rule prescribes that a plan is selected at random from those with the smallest premium, in effect all plans are treated as if they have the same expected AOOP costs, insofar as this is considered at all.

“Rational”: We assume that consumers form statistically realistic forecasts of MAOOP(k,Xt-1) for relevant information Xt-1, and that they choose a plan k to minimize ECIC(k,Xt-1) = Premiumk + MAOOP(k,Xt-1).22

The random and minimum premium benchmarks are simple heuristics that should be in the information sets of even minimally informed consumers.23 The “rational” model is the ultimate benchmark for “good” consumer decision-making in our analysis, but is also the most complex and computationally burdensome rule in that it requires specification of the year t-1 information available to and considered by the individual, and calculation of the conditional forecast MAOOP(k,Xt-1). Because of the high dimensionality of Xt-1 when it includes MCt-1, it is impractical to estimate nonparametrically the conditional density f(MCt | k,Xt-1) and use this to estimate directly the moment MAOOP(k,Xt-1). Instead, we use a “method of sieves” and a one-dimensional “sufficient statistic” for the impact of last year’s medicine cabinet to estimate this moment semiparametrically. Our method does not take advantage of the known fine structure of the nonlinear mapping CICt = FBD(MCtk, t), but with sufficient flexibility in the sieve specification we can in principle recover the relevant aspects of this structure from the data. To implement this procedure, we assume first that the static expectation CICSkt = FBD(MCt-1, k,t) is a sufficient statistic for the information conveyed by a consumer’s prior medicine cabinet MCt-1, and second that CICSkt and a limited number of other demographic and health characteristics in Xt-1 influence the conditional density of MCt through a single linear index H(k,Xt-1)βkt, where H is a vector of transformations of Xt-1 and βkt is a vector of parameters for each plan and year. This implementation is also consistent with an “adaptive expectations” model in which consumers start with the static expectation and adjust toward the average CIC for consumers with similar demographic and health attributes.

The rational decision rule requires specification of the set of variables on which expectations are conditioned. We are obviously limited by the scope of available data. In Heiss et al. (2012), we compare various specifications; here we consider only one specification that includes all available variables in Xt-1. These variables and transformations are defined as follows:

PFPCIC (Plan Finder predicted CIC), i.e., the static expectation CICSkt = FBD(MCt-1,k,t)

A linear spline in age

Gender

CCW, a vector of indicator functions of 23 chronic conditions derived from the Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW); see Appendix A. The CCW employs algorithms based on International Classification of Disease Version 9 (ICD-9) codes, the type of claim (inpatient, outpatient, physician services, etc.), and the number of claims within a given reference time period.24

CCW score, equivalent to the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) risk score calculated by Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The HCC risk score is a measure of expected drug costs based on diagnosis codes and demographic factors and is used by CMS to adjust Medicare Parts C and D payments to insurance plans.25

We assume that this “rational” consumer has ECIC(k,Xt-1) obtained by summing Premiumk and the best linear prediction obtained from a regression over the working sample of realized CICkt on the variables above, and selects a plan to minimize this ECIC.

Our primary measures of the quality of the consumer’s plan choice are population averages of the ex ante probabilities of expected excess spending and of the levels of expected excess spending, relative to each of the five benchmarks we consider. For the perfect foresight benchmark, this reduces to the average ex post wistful regret from failing to choose the plan that is ex post optimal. For the remaining benchmarks, all of which are arguably feasible, this gives population averages of excess spending probabilities and levels relative to decision rules the

4.3 Results

All simulations reported in this section are conducted for the entire working samples of 2007 and 2008 (data from 2006 is used to construct the variables that are the information for decisions made at the end of 2006 for plan year 2007). Due to the large samples, statistical sampling errors are negligible, and are not reported. Following our discussion in the previous section, the analysis takes an ex ante perspective to evaluate plan choices, with population averages of conditional expectations of our performance comparisons of actual and benchmark rule choices given prior year information estimated by unconditional empirical expectations of ex post realizations of these comparisons. For feasible benchmarks such as random, minimum premium, Plan Finder, and “rational”, these estimate the ex ante probability of excess spending and the expected level of excess spending. For the wistful benchmark of perfect foresight, this calculation reduces to ex post comparisons of the form that have appeared previously in the literature.

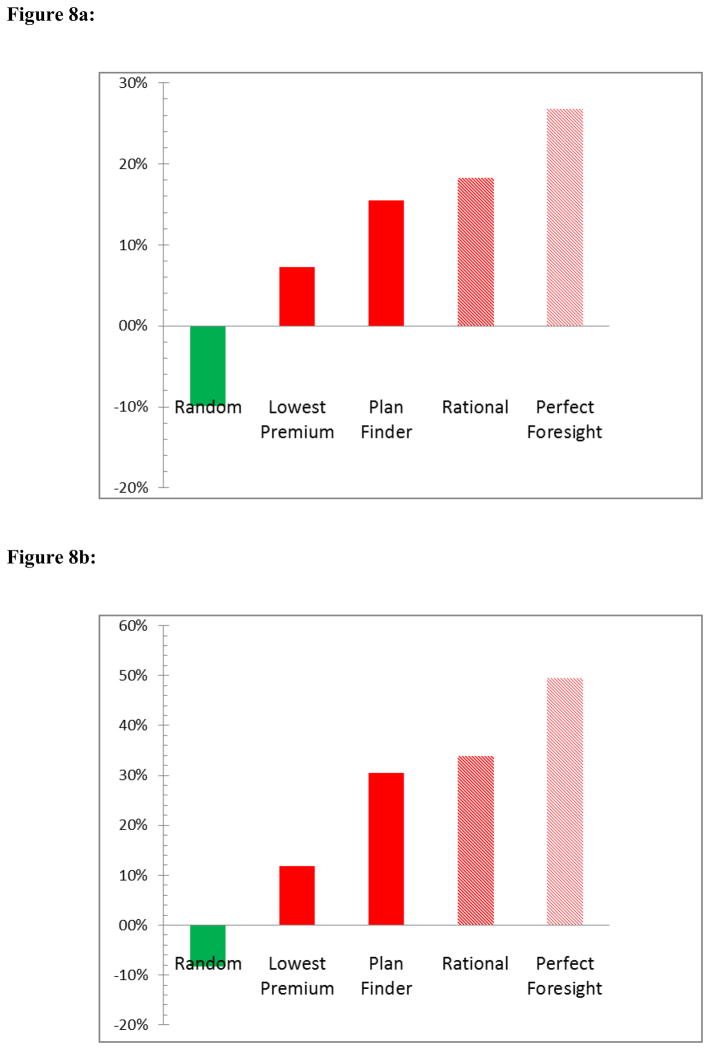

Table 6 reports our estimates of the population proportions of individuals whose actual plan choice is worse in terms of expected consumer inclusive cost than each of the benchmarks we consider, and our estimates of average overspending in (current) dollars per year. The higher these numbers, the worse consumers are doing relative to each benchmark. The top panel contains results for 2007 and 2008 plans without therapeutic substitution; the bottom panel for 2008 introduces therapeutic substitution. First, we observe in the case of no therapeutic substitution that the plans that individuals chose for 2007 and 2008 were rarely as good as Plan Finder, which itself is expected to be inferior to a “rational” plan that takes account of the probability of developing new health conditions that require additional drugs: In 2007, 78% of consumers would have been better off choosing the plan suggested by the Plan Finder; in 2008, this proportion was 75.5%. Average overspending compared to the plan suggested by Plan Finder was about $200 per year in both 2007 and 2008. Following the rational decision rule we described above results in very similar numbers.26 A simple feasible decision rule – choosing the cheapest plan – would still allow about two thirds of consumers to end up with lower total spending than in their actual choice. Perhaps even more surprisingly, about one quarter of consumers do worse than if they had chosen a plan at random; however, on average consumers would spend more with randomly chosen plans than with their actual choices, as indicated by the negative average overspending dollar amounts.

Table 6.

Actual plan choices vs. optimal choices implied by alternative decision rules

| 2007 and 2008; no therapeutic substitution

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share with higher spending

|

Avg. overspending

|

|||

| 2007 | 2008 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| Plan Finder | 78.0% | 75.5% | 197.91 | 195.68 |

| Random | 23.7% | 22.5% | −96.47 | −124.61 |

| Lowest premium | 66.0% | 65.1% | 115.52 | 91.25 |

| Rational | 77.4% | 76.7% | 196.06 | 230.57 |

| Perfect foresight | 93.7% | 89.1% | 315.05 | 338.53 |

| 2008; no therapeutic substitution vs. generic therapeutic substitution

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share with higher spending

|

Avg. overspending

|

|||

| No subst. | Subst. | No subst. | Subst. | |

| Plan Finder | 75.5% | 80.3% | 195.68 | 313.51 |

| Random | 22.5% | 27.5% | −124.61 | −85.95 |

| Lowest premium | 65.1% | 61.6% | 91.25 | 121.04 |

| Rational | 76.7% | 80.6% | 230.57 | 349.31 |

| Perfect foresight | 89.1% | 91.6% | 338.53 | 509.70 |

Notes: The table shows the share of chosen plans that resulted in higher spending than what would have been achieved with the plan choice implied by a bechmark decision rule; average of excess spending (in current dollars) implied by the chosen plan compared to the benchmark plan.

Our results for the perfect foresight rule, a benchmark that compares actual choice with the ex post optimum, indicate that 6.3% of consumers in 2007 achieve this optimum, while the remainder do worse; the proportion that were ex post optimal was slightly higher in 2008. Average ex post overspending was more than $300 dollars per year in 2007 compared to the perfect foresight benchmark.