Abstract

Introduction:

We evaluated the average time required to complete individual steps of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) by an expert RARP surgeon. The intent is to help establish a time-based benchmark to aim for during apprenticeship. In addition, we aimed to evaluate preoperative patient factors, which could prolong the operative time of these individual steps.

Methods:

We retrospectively identified 247 patients who underwent RARP, performed by an experienced robotic surgeon at our institution. Baseline patient characteristics and the duration of each step were recorded. Multivariate analysis was performed to predict factors of prolonged individual steps.

Results:

In multivariable analysis, obesity was a significant predictor of prolonged operative time of: docking (odds ratio [OR] 1.96), urethral division (OR 3.13), and vesico-urethral anastomosis (VUA) (OR 2.63). Prostate volume was also a significant predictor of longer operative time in dorsal vein complex ligation (OR 1.02), bladder neck division (OR 1.03), pedicle control (OR 1.04), urethral division (OR 1.02), and VUA (OR 1.03). A prolonged bladder neck division was predicted by the presence of a median lobe (OR 5.03). Only obesity (OR 2.56) and prostate volume (OR 1.04) were predictors of a longer overall operative time.

Conclusions:

Obesity and prostate volume are powerful predictors of longer overall operative time. Furthermore, both can predict prolonged time of several individual RARP steps. The presence of a median lobe is a strong predictor of a longer bladder neck division. These factors should be taken into consideration during RARP training.

Introduction

The introduction of the da Vinci robotic system (Intuitive Surgical, Inc.) has made a dramatic impact in the treatment of localized prostate cancer. Since first described in 2001, robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) has continued to gain widespread acceptance with less postoperative morbidity, reduced blood loss, along with some supportive data of improved early continence and erectile function recovery.1–3 For these reasons, over 80% of radical prostatectomies are performed robotically in the United States,4 as well as growing percentages globally. Moreover, acquisition of robotic skills is crucial in the early learning curve particularly for residents, fellows, and urologists already established in practice. However, lack of a standardized robotic training curriculum, coupled with reduced resident working hours, impose further difficulties in the mastering of robotic techniques during training.

The learning curve of RARP is complex as well as its definition. When using a 4-hour case proficiency, Ahlering and colleagues reported a RARP learning curve of 12 cases for a laparoscopic-naïve surgeon.5 In a recent report by Al-Hathal and colleagues, the RARP learning curve of a fellowship-trained surgeon was evaluated at 50 cases after which the positive surgical margin (PSM) rate in organ-confined disease was significantly reduced and the overall operative time (OT) was reduced by an average of 80 minutes.6 When using oncological outcome to define surgical proficiency, Herrell and colleagues reported a minimum learning curve of 150 cases to reduce the PSM rate after RARP to a level comparable to that obtained by open procedure.7 Murphy and colleagues also reported a RARP learning curve of >80 cases before a plateau is achieved.8 Obviously, the learning curve is quite variable which can be related to case volume, surgeon variability, and definition used.

To assess training proficiency from a unique perspective, we sought to evaluate the entire RARP procedure dividing it into its individual, sequential steps. Furthermore, we assessed the average time required to complete the individual RARP steps by an expert RARP surgeon. Our intent was to help establish a time-based benchmark during apprenticeship. In addition, we aimed to evaluate preoperative patient features that could prolong operative time of individual RARP steps.

Methods

Study population

After institutional review board approval, we prospectively collected and retrospectively analyzed data from 247 consecutive patients who underwent RARP at our institution (CHUM) between 2010 and 2014. A single fellowship-trained robotic surgeon (KCZ), with over 1500-case experience, performed all cases with no trainee involvement at the console. We have previously reported on our RARP surgical technique.9–11 No patient had previous pelvic radiation, neoadjuvant therapy, or previous endoscopic prostate surgery. Data collection included patient demographic and baseline parameters (age, body mass index [BMI], prostate-specific antigen [PSA], Gleason score, clinical stage, prostate volume at transrectal ultrasound [TRUS], International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS], Sexual Health Inventory for Men [SHIM]), overall operative time, and detailed intra-operative data, including time for each individual step.

Surgical steps and definition of timed segments

For academic and quality assessment purposes, we divided the RARP procedure into 10 individual steps. All times were independently collected by the dedicated robotic nursing team on a standardized institution worksheet. The individual RARP steps included:

Preparation step, which includes patient entry into the operating room, anesthesia, positioning, sterilization and draping.

Docking step, which starts from initial skin incision until complete docking of the robot.

Posterior dissection, which includes initial vas deferens division and seminal vesicles’ dissection.

Retzius space dissection, which includes detaching the bladder from the anterior abdominal wall, excising anterior prostatic fat pad, opening of the endo-pelvic fascia bilaterally, and sufficient dissection of the prostatic apex.

Dorsal venous complex (DVC) ligation, which includes applying 2 Vicryl suture ligations, 1 distal to provide hemostatic DVC control, and another more proximal for later prostate manipulation.

Bladder neck division, which includes complete division of bladder neck and delivery of seminal vesicles and vasa anteriorly.

Pedicle control, which starts with vascular pedicle dissection and Hem-o-lock control followed by bilateral management of the neurovascular bundles (interfascial, extrafascial or wide dissection).12

Urethral division, this step starts with the 4th arm Prograsp traction of the back-bleed DVC suture along with replacement of the urethral catheter. Monopolar scissor dissection through the controlled DVC and urethra are carried out with careful attention not to injure adjacent neurovascular bundles, prostatic apex all while optimizing urethral length. The time is recorded once the specimen and anterior prostate fat pad have been placed in the Endocatch (Covidien, Inc.) bag.

Lymph node dissection, which is performed bilaterally as previously described. Time is recorded upon placement of all nodal tissues in a separate Endocatch bag.13

Vesico-urethral anastomosis (VUA) reconstructive step. Time is recorded from the placement of the interlocked V-Loc sutures until its completion circumferentially followed by verification of water-tight closure with 300 mL instilled into the bladder.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the time required to complete each individual RARP step. Time percentiles were calculated for each step and a cut off of 75th percentile was chosen as the threshold for defining a prolonged step. The secondary outcome was to determine the presence of predictive factors that led to prolonged steps.

Statistical analysis

Data were prospectively collected for all parameters and analyzed retrospectively. All tests were two-sided and a p value 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. The IBM SPSS Statistics package (IBM Corporation, version 21, Armonk, NY) was used for analysis. The distribution of the variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk’s test. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics, and central tendency was measured with the median followed by the first and third quartiles (25%–75%). Continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann Whitney U test. The chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. Lastly, a binomial logistic model was used to assess the impact of a number of patient factors (age, BMI, D’Amico risk, prostate volume and presence of median lobe) on the likelihood of individual RARP steps to be prolonged ≥75th percentile.

Results

We evaluated 247 patients (Table 1). The median patient age was 61 years (inter-quartile range [IQR] 55–65), median PSA was 5 ng/mL (IQR 4–7), median prostate volume at TRUS was 40 mL (IQR 30–47), IPSS was 6 (IQR 3–12), and SHIM score was 22 (IQR 16–25). Of the total number of patients, 16.6% had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. The preoperative Gleason sum ≥7 accounted for 69.3% of patients and clinical stage T2 to T3 accounted for 16.4%. The D’Amico risk stratification group was low, intermediate, and high in 28.3%, 65.2% and 6.5%, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 247 patients who underwent RARP

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| No. patients | 247 |

| Age (years) | 61 (55–65) |

| Obesity (BMI) | |

| ≥30 | 41 (16.6%) |

| <30 | 206 (83.4%) |

| Preoperative PSA (ng/mL) | 5 (4–7) |

| Prostate volume at TRUS (mL) | 40 (30–47) |

| Clinical stage | |

| T1 | 206 (83.4%) |

| T2, T3 | 41 (16.6%) |

| Gleason score at biopsy | |

| 6 | 76 (30.8%) |

| 7 | 155 (62.8%) |

| >8 | 16 (6.5%) |

| D’Amico risk group: | |

| Low | 70 (28.3%) |

| Intermediate | 161 (65.2%) |

| High | 16 (6.5%) |

| IPSS score | 6 (3–12) |

| SHIM score | 22 (16–25) |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 200 (150–250) |

| QoL score | 1 (0–2) |

| Median lobe | |

| Present | 34 (14.2%) |

| Absent | 212 (85.8%) |

RARP: robot-assisted radical prostatectomy; IQR: interquartile range; BMI: body mass index; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; TRUS: transrectal ultrasound; IPSS: international prostate symptom score; SHIM: Sexual Health Inventory for Men; QoL: quality of life.

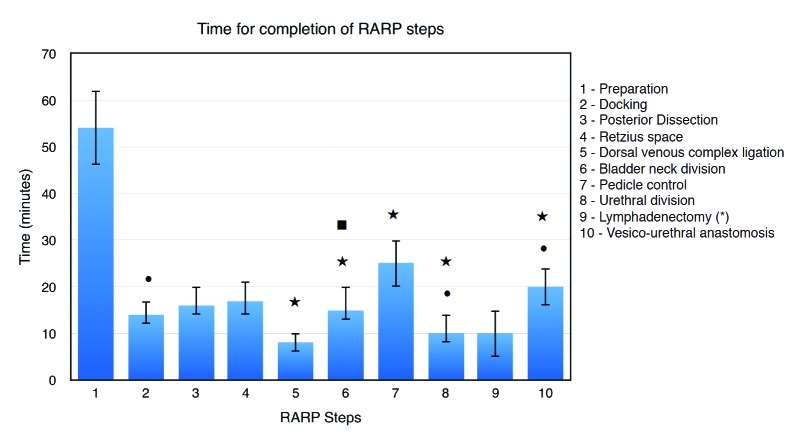

Intra-operatively, the median estimated blood loss was 200 mL (IQR 150–250) and a median lobe was present in 14.2% of patients. The median overall operative time at the robotic console was 149 minutes (IQR 132–171). The longest and shortest steps are the preparation and the DVC ligation, respectively (Table 2). Table 2 indicates the median operative time for each step.

Table 2.

RARP individual steps of the 247 patients

| RARP steps | N | Median time (min) | IQR | Min (min) | Max (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (overall) | 246 | 149 | 132–171 | 71 | 270 |

| Preparation (1) | 241 | 54 | 46–62 | 20 | 95 |

| Docking (2) | 240 | 14 | 12–17 | 7 | 42 |

| Posterior dissection (SV/VD) (3) | 243 | 16 | 14–20 | 5 | 47 |

| Retzius space dissection (4) | 235 | 17 | 14–21 | 7 | 42 |

| DVC ligation (5) | 235 | 8 | 6–10 | 3 | 35 |

| Bladder neck division (6) | 235 | 15 | 13–20 | 5 | 51 |

| Pedicle control + NVB preservation (7) | 240 | 25 | 20–30 | 8 | 72 |

| Urethral division and specimen entrapment (8) | 240 | 10 | 8–14 | 3 | 40 |

| Lymphadenectomy (9) | 19 | 10 | 5–25 | 4 | 35 |

| VUA + reconstruction (10) | 242 | 20 | 16–24 | 8 | 45 |

IQR: interquartile range; SV: seminal vesicles; VD: vas deferens; DVC: dorsal venous complex; NVB: neurovascular bundle; VUA: vesico-urethral anastomosis.

In multivariate analysis (Table 3), obesity was a significant predicting factor for prolonged duration of docking (odds ratio [OR] 1.96), urethral division (OR 3.13), and VUA (OR 2.63). Furthermore, prostate volume was a significant predictor for prolonged time of DVC ligation (OR 1.02), bladder neck division (OR 1.03), pedicle control (OR 1.04), urethral division (OR 1.02), and VUA (OR 1.03). In addition, the presence of a median lobe was a predictor of prolonged bladder neck division (OR 5.03). Only obesity (OR 2.56) and prostate volume (OR 1.04) were predictors of a longer overall operative time. However, age and D’Amico risk were not predictive of prolonged operative time OT. Figure 1 summarizes all 10 steps of RARP and their predicting factors.

Table 3.

Predictors of prolonged singular steps (≥75th percentile): Multivariate logistic regression

| Step | Variables | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate volume | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.01 | |

| Operative time (overall) | Obesity | ||

| Non-obese | Ref | ||

| Obese | 2.56 (1.21–5.42) | 0.01 | |

| Docking (2) | Obesity | ||

| Non-obese | Ref | ||

| Obese | 1.96 (1.15–3.34) | 0.01 | |

| Dorsal vein complex ligation (5) | Prostate volume | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.04 |

| Bladder neck division (6) | Median lobe | ||

| Absent | Ref | ||

| Present | 5.03 (2.21–11.42) | <0.01 | |

| Pedicle control, NVB preservation (7) | Prostate volume | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | <0.01 |

| Prostate volume | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.01 | |

| Prostate volume | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.03 | |

| Urethral division + specimen entrapment (8) | Obesity | ||

| Non-obese | Ref | ||

| Obese | 3.13 (1.45–6.76) | <0.01 | |

| Prostate volume | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | <0.01 | |

| (10) Reconstruction + VUA | Obesity | ||

| Non-obese | Ref | ||

| Obese | 2.63 (1.25–5.52) | 0.01 |

Each step was adjusted for the following variables: age, body mass index, prostate volume, D’Amico risk and presence of median lobe). VUA: vesico-urethral anastomosis; NVB: neuro-vascular bundle; OR: odds ratio.

Fig. 1.

Time for completion of RARP steps. Median (interquartile range) for 10 RARP surgical steps length. RARP: robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. •Obesity as a predictor of prolonged step in multivariable analysis. ⋆Prostate volume as a predictor of prolonged step in multivariable analysis. ■Median lobe as a predictor of prolonged step in multivariable analysis.

Discussion

In just over a decade, RARP has become the most commonly performed surgical procedure for localized prostate cancer in the United States.4 However, despite issues related to credentialing and training, there has been no standard RARP curriculum for trainees so far, even in the era of surgical simulators.14 In an attempt to help create reference expectations for residents and fellows at our tertiary, academic training centre, we sought to create time-based goals for the individual RARP steps. As such, we evaluated the time required to perform each RARP step by a fellowship-trained surgeon (KCZ) beyond his learning curve, with over 1500-case experience. More important, we wanted to assess the preoperative patient-related risk factors, which inferred prolonged time to complete those steps by an expert surgeon. The ultimate intent was to help designate the steps with regards to level of difficulty to help a trainee increase in complexity during apprenticeship. In addition, we aimed to take into account patient characteristics, which would further render certain steps more difficult for the novice surgeon.

We report, to the best of our knowledge, the first unique study that evaluates not only time of RARP step completion, but also the patient factors predicting prolonged operative time of those individual steps. The preparation, an anesthesia-based step, was the longest among all steps with a median time of 54 minutes (IQR 46–62). This can, perhaps, be explained by the lack of a dedicated anesthesia team in a universal medical system. The shortest step was the DVC ligation, with a median time of 8 minutes (IQR 6–10). Among all evaluated factors in multivariate analysis, prostate volume was a significant predictor for prolonged operative time of 5 individual steps, including DVC ligation (OR 1.02), bladder neck division (OR 1.03), pedicle control (OR 1.04), urethral division (OR 1.02), and VUA (OR 1.03). In addition, obesity was an independent predictor for prolonged duration of 3 steps, including docking (OR 1.96), urethral division (OR 3.13), and VUA (OR 2.63). Finally, the presence of a median lobe was a predictor of prolonged bladder neck division (OR 5.03). Only obesity (OR 2.56) and prostate volume (OR 1.04) were predictors of a longer overall operative time.

To the best of our knowledge, only few studies evaluated operative time of RARP. In a recent study of 100 consecutive patients, Rebuck and colleagues reported some modifications in operating room processes that are associated with significant reduction in operative time and cost of RARP. These processes include trainee adherence to time-oriented surgical goals, use of a dedicated anesthesia team, simultaneous processing by nursing and urology house staff during case turnover, and identification and elimination of unused disposable instruments;15 however, the study did not evaluate the operative time of individual steps. In a prospective study of 178 patients, Davis and colleagues reported the difference in operative time of individual RARP steps between trainees and faculty staff that was significantly higher for less experienced trainees (<40-case experience).16 In addition, the study demonstrated important guidelines for trainees during RARP procedures, including goals to achieve and pitfalls to avoid. Another study of 100 patients, reported risk factors of prolonged overall operative time after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy that included prostate volume, surgeon experience, sural nerve grafting, and use of a robotic system.17

As far as training is concerned, we report median times of individual steps of RARP performed by an expert robotic surgeon to possibly be used as benchmarks during apprenticeship. Furthermore, we report risk factors of prolonged operative time of those steps, as we believe they can help in trainee-step selection, particularly when a risk factor does exist. For instance, if a large median lobe is anticipated, the trainee is directed towards steps easier than bladder neck division, such as Retzius space dissection. Furthermore, we can also break down the steps according to the experience level of individual trainees, such that new trainees will be assigned to docking, Retzius space dissection, DVC suture, and posterior dissection; intermediate trainees will be assigned to bladder neck division, lymph node dissection, and VUA; advanced trainees will be assigned to pedicle division and urethral division.

Aside from the important role of assessing trainees’ technical skills during robotic-assisted surgery,18,19 some authors also reported on other tools for assessing non-technical skills (cognitive assessment). Cognitive workload has been defined as the level of mental effort exerted during a task. Guru and colleagues have found that the cognitive assessment in 10 participating surgeons of different levels of experience (beginners, proficient, and expert) was a more effective method in differentiating the level of expertise between them than previously used objective methods.20 Nevertheless, for a proper assessment process to be ensured, Brunckhorst and colleagues suggested integrating and standardizing both technical and non-technical assessment methods.21

Given the paucity of data evaluating operative time of individual RARP steps and their predicting factors, we believe our study is an important forward step in future training curricula of RARP. However, it is not devoid of limitations including its retrospective nature, single surgeon and single institute experience. Another limitation is the inability to test other risk factors that could have had an impact on operative time, such as history of previous surgery; there was insufficient data gathering regarding patients’ surgical history in our database. Also, it was difficult to evaluate predictors of prolonged lymphadenectomy because of the small number of high-risk patients. In addition, we did not assess time of specimen extraction and wound closure, as our main objective was to assess robot-related steps. However, both steps were included in the overall operative time. Furthermore, we did not assess quality of work since an expert surgeon solely performed all cases. The goal was to assess preoperative factors that may have prolonged individual steps. In the novice/intermediate users, these steps may be even more challenging. From a training standpoint, utilizing these times for a novice/intermediate surgeon may be of limited value in assessing surgeon competency – “being fast doesn’t always mean good.” As such, it is important to assess efficacy, economy of motion, and quality of work done by trainees; it is also important to assess postoperative complications, which are also a measure of competency and expertise. However, we did not take these into account, which is another limitation of our study.

Conclusions

Prostate volume and obesity are independent predictors of longer overall operative time of RARP in experienced surgeons. Furthermore, both prostate volume and obesity can predict prolonged time of several individual RARP steps. The presence of a median lobe is also a strong predictor of longer bladder neck division. These preoperative factors should be considered during RARP training.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Abdullah M. Alenizi acknowledges the Security Forces Hospital in Riyadh for scholarship support of his fellowship training in robotic surgery

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial or personal interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Kaul S, Savera A, Badani K, et al. Functional outcomes and oncological efficacy of Vattikuti Institute prostatectomy with Veil of Aphrodite nerve-sparing: An analysis of 154 consecutive patients. BJU Int. 2006;97:467–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.05990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsons JK, Bennett JL. Outcomes of retropubic, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted prostatectomy. Urology. 2008;72:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson T, Torrey R. Open versus robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: Which is better? Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:200–5. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32834493b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowrance WT, Parekh DJ. The rapid uptake of robotic prostatectomy and its collateral effects. Cancer. 2012;118:4–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahlering TE, Skarecky D, Lee D, et al. Successful transfer of open surgical skills to a laparoscopic environment using a robotic interface: Initial experience with laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003;170:1738–41. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000092881.24608.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hathal N, El-Hakim A. Perioperative, oncological and functional outcomes of the first robotic prostatectomy program in Quebec: Single fellowship-trained surgeon’s experience of 250 cases. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:326–32. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrell SD, Smith JA., Jr Robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: What is the learning curve? Urology. 2005;66(5 Suppl):105–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy DG, Bjartell A, Ficarra V, et al. Downsides of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Limitations and complications. Eur Urol. 2010;57:735–46. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdivieso RF, Hueber PA, Zorn KC. Robot assisted radical prostatectomy: How I do it. Part II: Surgical technique. Can J Urol. 2013;20:7073–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valdivieso RF, Hueber PA, Zorn KC. Robot assisted radical prostatectomy: how I do it. Part I: Patient preparation and positioning. Can J Urol. 2013;20:6957–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorn KC, Widmer H, Lattouf JB, et al. Novel method of knotless vesicourethral anastomosis during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Feasibility study and early outcomes in 30 patients using the interlocked barbed unidirectional V-LOC180 suture. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:188–94. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zorn KC, Gofrit ON, Steinberg GP, et al. Planned nerve preservation to reduce positive surgical margins during robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2008;22:1303–9. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zorn KC, Katz MH, Bernstein A, et al. Pelvic lymphadenectomy during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Assessing nodal yield, perioperative outcomes, and complications. Urology. 2009;74:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zorn KC, Gautam G, Shalhav AL, et al. Training, credentialing, proctoring and medicolegal risks of robotic urological surgery: Recommendations of the society of urologic robotic surgeons. J Urol. 2009;182:1126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rebuck DA, Zhao LC, Helfand BT, et al. Simple modifications in operating room processes to reduce the times and costs associated with robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2011;25:955–60. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis JW, Kamat A, Munsell M, et al. Initial experience of teaching robot-assisted radical prostatectomy to surgeons-in-training: Can training be evaluated and standardized? BJU Int. 2010;105:1148–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2009.08997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Feel A, Davis JW, Deger S, et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy--an analysis of factors affecting operating time. Urology. 2003;62:314–8. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abboudi H, Khan MS, Aboumarzouk O, et al. Current status of validation for robotic surgery simulators - a systematic review. BJU Int. 2013;111:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goh AC, Goldfarb DW, Sander JC, et al. Global evaluative assessment of robotic skills: Validation of a clinical assessment tool to measure robotic surgical skills. J Urol. 2012;187:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guru KA, Esfahani ET, Raza SJ, et al. Cognitive skills assessment during robot-assisted surgery: Separating the wheat from the chaff. BJU Int. 2015;115:166–74. doi: 10.1111/bju.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunckhorst O, Ahmed K. Cognitive training and assessment in robotic surgery - is it effective? BJU Int. 2015;115:5–7. doi: 10.1111/bju.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]