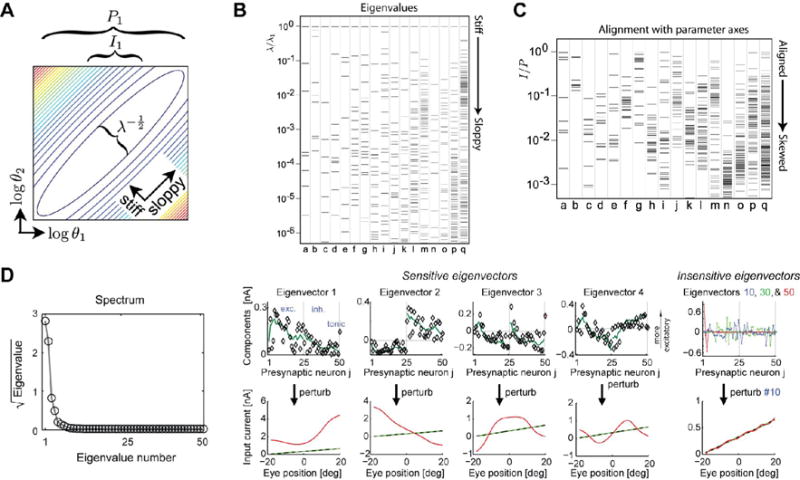

Figure 1.

In high-dimensional biological models there are often many parameter combinations that can co-vary without significant effect on the behavior of the model, known as sloppy parameter combinations [8**]. (A) Elliptical level sets in the deviation of model output from a nominal value (computed from the Hessian, or second derivative) shows a direction in which parameter variation does not change model behavior (sloppy direction) and an orthogonal direction in which the model is sensitive (stiff). The major and minor axes of these ellipses (and thus the relative sensitivity to the stiff/sloppy directions) are determined by the eigenvalues, λi, and the projections of these onto the parameter axes (θ1, θ2) parameter axes are denoted by P1 and I1, respectively. (B) Eigenvalues computed for 17 different systems biology models [8**], including detailed models of circadian transcriptional circuits and yeast metabolism (a–q) are spread evenly across many orders of magnitude. Only the first few eigenvectors have significant effects on the behavior of the model, thus only a few parameter directions determine model behavior. (C) The alignment of the ‘error ellipsoids’ I/P relative to model parameters shows that most eigenvectors tend to be composed of many underlying parameters (tend to be skewed). Thus, while there are relatively few stiff directions in parameter space that change model behavior, these directions usually have contributions from many experimentally measurable parameters. (D, left) A computational model of an oculomotor circuit [5**] shows similar sensitivity to only four or five parameter combinations (D, right) to the systems biology models (A–C). The sensitive directions, projected onto the underlying parameter axes (presynaptic input weights) have substantial contributions from all parameters. Figures (A–C) reproduced from [8**], (D) Reproduced from [5**].