Abstract

Objectives:

This study was undertaken to review the caesarean section rate and perinatal mortality in Federal Medical Centre, Birnin Kudu from 1st January 2010 to 31st December, 2012.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective study involving review of 580 case files. Ethical clearance was obtained. The records of labour ward, neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) and operating theatre were use. Information extracted includes age, parity, booking status, total deliveries, indications for caesarean section and perinatal outcome from 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2012 at Federal Medical Centre, Birnin Kudu. The data obtained was analysed using SPSS version 17.0 statistical software (Chicago, Il, USA). Absolute numbers and simple percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Association between caesarean section and perinatal mortality was determined using Pearson's Coefficient of correlation and student t- test. P - value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result:

This study reported a caesarean section rate of 17.69 % and a perinatal mortality rate of 165.6 per 1000. Majority of the babies (78.2%) were within normal weight. The mean age of the women was 25.9 ± 6.2 years and mean parity was 4 ± 3. Majority of them were uneducated and unemployed. Obstructed labour was the commonest indication for emergency caesarean section accounting for 31.7% of caesarean sections and foetal distress was the least at 2.6 %. Two or more previous caesarean section was the commonest indication for elective caesarean section (17.1%) and bad obstetrics history the least indication (1.4%). There is a weak positive correlation (r = 0.35) between caesarean section rate and perinatal mortality and this association was not statistically significant (P = 0.12).

Conclusion:

Caesarean section and perinatal mortality rates in the present study are comparatively high. Absence of significant correlation means that a high caesarean section rate is not likely to improve perinatal outcomes in babies of normal weight; therefore the caesarean section rate in this centre should be reduced. Measures to reduce perinatal mortality such as skilled attendant in labour and training of medical staff in neonatal resuscitation should be adopted.

Keywords: Caesarean section, north-west Nigeria, perinatal outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Caesarean section is deemed necessary when an attempt at vaginal birth is dangerous to the mother, baby or both. It is the commonest major surgery in obstetrics and it has contributed to improved obstetric care throughout the world.1 Like any other major abdominal surgery, caesarean section is not devoid of complications. These complications contribute to maternal morbidity and mortality in our environment.2 Maternal mortality is 10–20 times greater than vaginal delivery.3

The perinatal mortality and morbidity associated with caesarean section is significantly related to the indication, characteristics of the patient, quality of antenatal care and experience of the surgeon. Reports from Pakistan and other low-resource settings indicate that substandard care, inadequate training, low staff competence and a lack of resources, including equipment and medication, are all factors that contribute to neonatal deaths.4,5 A number of studies have shown that high caesarean section rates are not associated with better perinatal outcomes in vertex presentation with weight above 2.5 kg.6,7,8

The UN recommends a caesarean section rate of 5–15 % to optimally minimize maternal and neonatal mortality rates.9 Great Britain and as in most developed nations have almost doubled the recommended UN caesarean section rate.10 while a 10 % caesarean section rate was reported from Ethiopia.11 In Nigeria, a caesarean section rate of 10.2–34.7 % has been reported in some Teaching Hospitals.12,13,14,15,16

Caesarean section is often done as an emergency procedure in women with cephalo pelvic disproportion, obstructed labour, foetal distress, antepartum haemorrhage and previous caesarean section resulting in high perinatal and maternal morbidities.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 Elective caesarean section may be indicated in women with two or more previous caesarean sections, after successful repair of vesico-vaginal fistula, major degree placenta praevia, abnormal lie, foetal macrosomia, prolonged infertility and in women with bad obstetrics history.

There has not been study done to determine the caesarean section rate and perinatal mortality in Federal Medical Centre, Birnin Kudu. This study was therefore undertaken to review the caesarean section rate and perinatal mortality in Federal Medical Centre, Birnin Kudu from 1st January 2010 to 31st December, 2012.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study of caesarean sections performed from 1st January 2010 to 31stst December 2012 at the Federal Medical Centre, Birnin Kudu, Jigawa State. Birnin Kudu is a town and a local government headquarters in the south of Jigawa state of Nigeria. According to the 2006 population census, it had a population of 333, 757 inhabitants and they are predominantly Muslims and Hausa/Fulani by ethnicity. Their major occupation is farming. Birnin Kudu is about 130 km south east of Kano city, the commercial nerve centre of northern Nigeria. The Federal Medical Centre is a tertiary health facility. It serves the health care needs of the people in the community and also receives referrals from other hospitals in the state and neighbouring northern states like Kano and Bauchi. The hospital is a 250 bedded facility with 3 resident consultant Obstetrician and 6 Medical officers in Obstetrics and Gynaecology department while a resident Consultant paediatrician supervises the medical officers in the Special care Baby unit. All the Medical officers can provide emergency obstetric care. The records of labour ward, special care baby unit and operating theatre were used to identify the total number of deliveries, total number of caesarean sections performed and the perinatal mortality over the period in view. The case notes of patients who had caesarean section were retrieved from the records department and the following information were extracted: Age, parity, booking status, indications for caesarean section and perinatal outcome. Ethical approval was sought from the ethics and research committee of the institution. No postmortem was done for the mother or neonate that died during this period in consonance with the belief and tradition of the people. The data obtained was analysed using SPSS version 17.0 (Chicago Il, USA). Absolute numbers and simple percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Similarly, quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency (mean, median) and measures of dispersion (range, standard deviation) as appropriate. Association between caesarean section and perinatal mortality was determined using Pearson's coefficient of correlation and students’ t-test. P - value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULT

During the period from 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2012, there were a total of 3335 deliveries out of which 590 were by caesarean section giving a caesarean section rate of 17.69 %. Of the 590 caesarean deliveries, 580 case notes were retrieved giving a retrieval rate of 98.3 %.

A total of 96 out of 580 babies died within the first one week of caesarean delivery, giving a perinatal mortality rate of 165.6 per 1000.

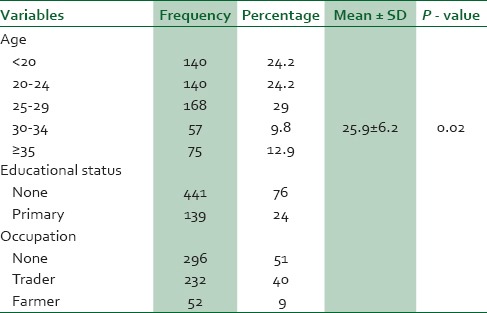

The mean age and parity of the women were 25.9 ± 6.2 years and 4 ± 3 respectively. Majority of them were uneducated and unemployed [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics of the study group (N = 580)

Most of the patients were primiparous women and unbooked [Table 2]. Obstructed labour was the most common indication for emergency caesarean section accounting for 31.7 % of caesarean sections. Obstructed labour was the commonest indication for emergency caesarean section accounting for 31.7 % of caesarean sections and foetal distress was the least at 2.6 %. Two or more previous caesarean section was the commonest indication for elective caesarean section (17.1 %) and bad obstetrics history (1.4 %) the least indication. [Table 3].

Table 2.

Distribution of obstetrics characteristics of the study group (N = 580)

Table 3.

Indications for Caesarean Section

Caesarean section rate shows a falling trend [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Trend of caesarean section during the period under review, 2010-2012

About 16.56 % of babies were delivered dead or died within the first week of birth. Most of the neonates (78.2 %) were of normal weight [Table 4]. There is a weak positive correlation (r = 0.35) between caesarean section rate and perinatal mortality and this association was not statistically significant (P = 0.12).

Table 4.

Perinatal outcome

DISCUSSION

Caesarean section rate of 17.69 % and perinatal mortality rate of 165.6 per 1000 were found in this study. The average age of the women was 25.9 ± 6.2 years and most were primiparous with mean parity of 4 ± 3.

The present study reports a caesarean section rate of 17.69 %. The caesarean section rate is similar to 17.9 % of a previous study done in Iceland, which reported a lower perinatal mortality of 1.7 per 1000.7 As in the present study the authors did not find any significant correlation between caesarean section rate and perinatal mortality.7 The present study also reported that most of the babies were within normal weight and as in previous study, caesarean section is not associated with a reduced perinatal mortality rate in babies above 2.5 kg.7 The caesarean section rate in the present study was higher than 10.3 % in Enugu,19 10.5 % (Makurdi),21 11.4 % (Zaria),13 15.8 % (Jos),22 but lower than 20.3 % reported in Birnin-Kebbi.23 These differences are possibly due to referral nature of our centre, high prevalence of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and use of repeat caesarean section for patients with a previous caesarean section. Rates of 16.9 % and 18 % reported in studies done in southwest, Nigeria were similar to that of the present study.24,25

Emergency caesarean section rate of 90.4 % reported in the present study is higher than those reported by Aisien,20 Okonofua26 and Nwobodo27 but lower than 97.4 % reported by Buowari.28 The implication is that perinatal mortality rate may continue to rise until caesarean section is done as elective rather than emergency procedure.

The most common indication for caesarean section was obstructed labour/cephalopelvic disproportion and this was consistent with studies from Kaduna,12 Zaria,13 Birnin Kebbi23 and Ilorin.25 In contrast, Ugwu et al., and other series reported that previous caesarean sections is the commonest indication for caesarean section followed by cephalopelvic disproportion.29,30 The reports of the present study are also in contrast to the findings of Adinma,31 Aisien,20 and Okonofua.26 Malnutrition and chronic infection impair pelvic bone development.32 Haemoglobinopathies especially sickle cell anaemia is also common in sub-saharan Africa. The women in the setting of this study are also given to marriage at very tender age when their pelvis is barely developed for parturition. All these predispose our women to cephalo-pelvic disproportion/obstructed labour.

The perinatal mortality rate of 165.6 per 1000 found in this review is similar to 162 per 1000 reported by Onwuhafua12 but higher than 95.7 per 1000 reported by Adinma,32 81.6 per 1000 reported by Aisien20 and 61.4 per 1000 reported by Okonofua.26 Prolonged obstructed labour and preeclampsia/eclampsia are associated with severe foetal asphyxia and death if delivery is unduly delayed.2,12 Sociocultural and economic factors interact to affect health seeking behaviour of our pregnant women, who patronize quacks for health care and only present to hospital at late hours with complications.33 These may explain the high perinatal mortality rates.

Caesarean section rate in the present study is comparatively high and perinatal mortality rate is high compared to similar studies carried out in similar setting. Absence of significant correlation means that a high caesarean section rate is not likely to improve perinatal outcomes in babies of normal weight; therefore the caesarean section rate in this centre should be reduced. Other measures to reduce perinatal mortality such as availability of trained attendant at birth and training of medical staff on neonatal resuscitation should be adopted.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nkwo OP, Onah HE. Feasibility of reducing caesarean section rate of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu-Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;19:86–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezechi OC, Fasuba OB, Dare FO. Socioeconomic barriers to safe motherhood among booked patients in rural Nigerian communities. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;20:32–4. doi: 10.1080/01443610063426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bern Stein P. Strategies to reduce the incidence of Caesarean Delivery part I: Management of Breech Presentation. 200. Oct 12th, [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 25]. Available from: http\\womenshealthmedscape.com\medscape\wo\2000\FIGOpnt.html .

- 4.Hasan IJ, Khanum A. Health care utilization during terminal child illness in squatter settlements of Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2000;50:405–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korejo R, Bhutta S, Noorani KJ, Bhutta ZA. An audit and trends of perinatal mortality at the Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jónsdóttir G, Bjarnadóttir RI, Geirsson RT, Smárason A. No correlation between rates of caesarean section and perinatal mortality in Iceland. Laeknabladid. 2006;92:191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonsdottir G, Smarason AK, Geirsson RT, Bjarnadottir RI. No correlation between cesarean section rates and perinatal mortality of singleton infants over 2,500 g. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:621–3. doi: 10.1080/00016340902818196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonas HA, Lumley JM. The effect of mode of delivery on neonatal mortality in very low birthweight infants born in Victoria, Australia: Caesarean section is associated with increased survival in breech-presenting, but not vertex-presenting, infants. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1997;11:181–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1997.d01-19.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, Bing-Shun W, Thomas J, Van Look P, et al. Rates of caesarean section: Analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21:98–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black C, Kaye JA, Jick H. Cesarean delivery in the United Kingdom: Time trends in the general practice research database. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:151–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000160429.22836.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tedesse E, Adane M, Abiyou M. Caesarean section deliveries at Tikus Anbessa Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1996;73:619–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onwuhafua PI. Perinatal mortality and caesarean section at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Kaduna, Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;6:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sule ST, Matawal BI. Comparison of indications for caesarean section in Zaria, Nigeria: 1985 and 1995. Ann Afr Med. 2003;2:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okonta PI, Otoide VO, Okogbenin SA. Caesarean section at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital Revisited. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;20:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feyi-Waboso PA, Aluka, Kamami CI. Emergency caesarean section at Aba-Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;19:24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akinwutan AL, Oladokun A, Morhanson-Bello O, Ukaigwe A, Olatunji F. Caesarean Section at the turn of the millennium - A 5 year review, The university College Hospital, Ibadan Experience. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;23:13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Megafu U. Maternal mortality from emergency caesarean section in booked hospital patients at the Univeristy of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;1:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chama CM, El-Nafaty AU, Idrisa A. Caesarean morbidity and mortality at Maiduguri, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;20:45–8. doi: 10.1080/01443610063453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onwudiegwu U, Makinde ON, Ezechi OC, Adeyemi A. Decision-caesarean delivery interval in a Nigerian university teaching hospital: Implication for maternal morbidity and mortality. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;19:30–3. doi: 10.1080/01443615.1999.12452862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aisien AO, Lawson JO, Okolo A. A two year study of caesarean section and perinatal mortality in Jos, Nigeria. Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;71:171–3. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swende TZ, Agida ET, Jogo AA. Elective caesarean section at the Federal Medical Centre Makurdi, north-central Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2007;16:372–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutihir JT, Daru PH, Ujah IO. Elective caesarean section at Jos university teaching hospital. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;22:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nwobodo EI, Wara HL. High caesarean section rate at Federal Medical Centre Birnin-Kebbi: Real or apparent? Niger Med Pract. 2004;46:39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimoh AA. Primary caesarean section at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin: A 4 year review. Niger Hospital Pract. 2007;1:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ijaiya MA, Aboyeji PA. Caesarean delivery: The trend over a ten-year period at Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Surg Res. 2001;3:11–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okonofua FE, Makinde ON, Ayangade SO. Yearly trends in caesarean section and caesarean mortality at Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;1:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nwobodo EI, Isah AY, Panti A. Elective caesarean section in a tertiary hospital in Sokoto, north western Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2011;52:263–5. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.93801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buowari YD. Indications for caesarean section at a Nigerian District Hospital. Niger Health J. 2012;12:43–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugwu EO, Obioha KC, Okezie OA, Ugwu AO. A five-year survey of caesarean delivery at a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011;1:77–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okezie AO, Oyefara B, Chigbu CO. A 4-year analysis of caesarean delivery in a Nigerian teaching hospital: One-quarter of babies born surgically. J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;27:470–4. doi: 10.1080/01443610701405945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adinma JI. Caesarean section: A review from Sub-Urban Hospital in Nigeria. Niger Med J. 1993;24:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onsrud L, Onsrud M. Increasing use of caesarean section in developing countries. Tiddsskr nor Laege Foren (English Translation from Medline Search) 1996;116:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ugwa EA, Ashimi A. An assessment of stillbirths in a tertiary hospital in Northern Nigeria. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;10:1–24. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.961416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]