Abstract

Objective

The study was conducted to assess the usefulness by qualitative comparison between the two intravenous sedative drugs, Diazepam and Propofol and to provide sedation in apprehensive and uncooperative patients undergoing day care oral surgical procedures.

Methods

The present study was conducted on 20 adult patients, 10 in each group (Propofol and Diazepam) irrespective of age and sex. Intravenous sedation of Propofol compared with Diazepam in terms of onset of action, recovery, and anterograde amnesia, patient co-operation, surgeon’s convenience and side effects and other parameters.

Results

Propofol was found to be the superior sedating agent compared to Diazepam, having rapid onset and predictability of action, profoundness of amnesia and a faster recovery period, offering advantages of early patient discharge and better patient compliance.

Conclusion

Propofol was found to be an ideal sedating agent in day care oral surgical procedures.

Keywords: Propofol, Diazepam, Sedation

Introduction

Anxiety towards dental procedures varies from a suppressed fear of pain to phobia. This may make dental therapy difficult. Not only do many patients find these procedures unpleasant but they may also exhibit enhanced sympathetic activity such as xerostomia, tachycardia, sweating and tremors, which in some cases may lead to anxiety induced arrhythmias and vasovagal reactions [1].

Local anesthetics and new advances in technology have rendered dental treatment expedient and often painless. But in certain situations pain and anxiety control becomes unattainable by local anesthetics and the administration of local anesthesia is considered to be a traumatic procedure by many patients. General anesthesia is also not practical for many ambulatory patients undergoing minor surgical procedures, and hence the alternative approach is the use of anxiolytic and sedative agents as adjuncts to local anesthesia.

Intravenous sedative-hypnotics are commonly used during day care oral surgical procedures to enhance patient comfort, improve operating environment and prevent recall of unpleasant events during surgery [2].

The Wylie report defines conscious sedation as a technique in which the use of a drug or drugs produces a state of depression of CNS, which enables an operator to carry out a surgical procedure, but during which verbal contact with the patient is maintained and patient retains protective reflexes [3]. Among the methods used for conscious sedation, intra-venous sedation is perhaps the most popular, as it has rapid onset and enables the dose of the drug to be titrated according to the need of the patient, with maximum safety [4].

Hence a study has been undertaken to assess the usefulness of Propofol as a sedating agent in day care oral surgery and compare it with Diazepam in terms of onset of action, recovery, and anterograde amnesia, patient co-operation, surgeon’s convenience and side effects.

Pharmacology

Propofol

Propofol (2,6, di-isopropyl phenol) is one of a group of alkyl phenols with anesthetic properties.

Propofol is a short acting rapidly metabolized intravenous anesthetic [5], used both for induction and maintenance of General Anesthesia, as well as for sedation during local or regional anesthesia and for intensive care unit as an infusion [5].

Mechanism of Action

Inhibits activity at both spinal and supraspinal synapses by interacting with the gamma amino butyric (GABA) receptor complex to potentiate GABA-mediated effects [6]. Propofol induces hypnosis through its effects on the alpha subunit of GABA receptors [7].

Clinical Applications [5]

Used in ambulatory surgery (day care surgery).

Used in balanced anesthesia during general surgery.

Used in intensive care unit.

Diazepam

Diazepam (7 chloro-1,3 dihydro-1 methyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,4 benzodiazepine-2 one) grouped under benzodiazepine category of drugs, became available as Valium in 1963.

Mechanism of Action

Diazepam exerts its anti-convulsant and sedative properties centrally and is mediated by gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [11]. Decreased GABA reuptake from the synaptic clefts leads to excess GABA and inhibition of excitatory impulse transmission.

Anxiloytic and muscle relaxant action probably results from glycine mimetic actions of benzodiazepines in the brain stem and spinal cord respectively [10].

Clinical Application

CNS—effects of Diazepam range from mild sedation to full general anesthesia depending upon the dosage and preparation used.

It causes—Amnesia, anti-convulsant action, muscle relaxation and analgesia [12].

CVS—Haemodynamic effects of Diazepam is dose related, the higher the plasma level, the greater the decrease in systolic blood pressure [12].

Respiratory effects—produces dose related central respiratory system depression.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in the department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, College of Dental Sciences, Rau on an outpatient basis. The study included 20 adult patients, 10 in each group (Propofol and Diazepam) irrespective of age and sex.

Apprehensive and uncooperative patients requiring surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars under local anesthesia were included in the study. The procedure was explained to the patients and a written informed consent was obtained. A detailed case history, including past exposure to anesthetics, sedative agents and previous surgical procedures were collected and recorded.

Routine blood investigations were carried out and a chest X-ray and ECG was done for all patients above 50 years of age. A pre-anesthetic evaluation and Physician’s clearance was obtained for all patients.

Inclusion Criteria

Age group was between 14 and 55 years. Only American Society of Anesthesiology risk category I (ASA I) patients, after a complete medical history and physical examination, were included in the study.

Patients with no history of sensitivity to any drugs or their constituents were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who were pregnant, used sedative regularly, drug or alcohol dependent and had been previously given general anesthetic for dental procedures were excluded from the study.

Procedure

Patients were asked to remain nil orally 6 h prior to surgery. In the operating room, on arrival the patient was connected to a multi function HEWLETT PACKARD 78352 C Monitor and a no. 20 G cannula inserted in a vein on the forearm of the non-dominant arm. Upon completion of the procedure, the patients were observed for 10 min and later shifted and allowed to recover in the recovery room.

Patients were categorized into two groups, group P and D with 10 patients in each group at random.

Patients in Group P received Propofol, given 0.7 mg/kg body weight as an induction dose [14] and later slow intermittent bolus doses of 15 mg every minute, titrated to the required end point of sedation i.e., ptosis and slurred speech [5]. Patients in Group D received intravenous doses of Diazepam titrated to the required end point. This end point was chosen because it was easy to observe since the study was conducted in a hospital with an experienced anesthetist.

Repeat doses of Propofol and Diazepam were given after the signs of waning of sedation were seen like phonation, nystagmus and purposeful movements on surgical stimulation.

Patients were given local anesthetic injection of 2 % lignocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline solution 2–3 min after the administration of intravenous sedation. The amount of local anesthesia injected was noted.

Parameters Evaluated

Heart rate

Systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure

Oxygen saturation

Electrocardiogram (specifically lead II)

Onset of time of action

Amnesia—Retrograde amnesia–Anterograde

Recovery period (Time and Events)

Patient’s co-operation and level of sedation

Operating conditions and surgeon’s convenience

Side effects

Necessity of emergency support.

In the operating room multifunction Hewlett Packard Monitor with pulse oximeter, ECG monitor and NIBP were connected to the patient.

Real time monitoring of heart rate, systolic, diastolic, mean arterial pressure and oxygen saturation were made. Electrocardiogram was monitored on an oscilloscope screen during the whole operative period and recordings were made of any abnormal rhythm detected. These recording were made

15 min before the surgical procedure

Immediately after local anesthetic administration

Every 15 min during the surgery

10 min after the completion of surgery

At discharge

Onset of Action: calculated by the time elapsed between induction and the onset of the signs of end point of sedation.

Amnesia

Amnesia period and quality were evaluated with the help of a post-operative questionnaire regarding surgical procedures and by presenting separate visual and cutaneous tactile stimuli during surgery.

Amnesia was assessed after the surgery and just before discharge by means of a checklist asking if the patients remembered.

Visual and cutaneous stimuli were applied to check anterograde amnesia. Recall of venipuncture on the hand prior to the administration of any medication, was used to assess retrograde amnesia. The correct, partial or no recall of either of these parameters were used to grade the degree of anterograde amnesia as good, moderate or poor.

Recovery

Recovery period was measured from last dose of the drug to the time, when the patient could walk in a straight line without support. Recovery was assessed by the patient’s performance on a Peg Board Test and patient’s ability to walk in a straight line without support. Peg Board Test was used as a measure to test the psychomotor ability of the patient, following sedative administration. In this, the time taken by the patient to move the pegs from one side of the board to the other is noted after familiarization with the method, prior to administering the drug [15].

Patients performed this test once pre-operatively (base line ability) and then post-operatively at 15, 30, 60, 90 min and at the time at which the patients could walk in a straight line without support.

Patients were asked to walk in a straight line without support under supervision. If the patient could do this, they were assessed as fit for discharge. If they could not, they were rested and allowed to recover and again asked to walk in a straight line after 15 min.

Patients Co-operation

Patients co-operation and level of sedation was assessed by Ramsay Sedation Score [16] as

- Score 1

Anxious, agitated, restless

- Score 2

Co-operative, tranquil

- Score 3

Sedated, but responsive to commands

- Score 4

Asleep, brisk response to sound or glabellar tap

- Score 5

Asleep, sluggish response to sound or glabellar tap

- Score 6

Asleep, no response to sound or glabellar tap

Operating Conditions and Surgeon’s Convenience

Operating conditions were graded by the oral surgeon at the end of the procedure as excellent, good, moderate and poor using the degree of patient cooperation, accessibility to the operating field and body/tongue movements as guidelines.

Observations and Results

The study comprised of 20 patients divided into two groups of 10 each.

Group P—patients who received Propofol

Group D—patients who received Diazepam

Age and Sex Incidence

The age and sex incidence shows a mean age of 22.6 years in group P and 25.6 years in group D. The male:female ratio was 4:6 in group P and 7:3 in group D.

Duration of Surgery

The mean duration of surgery shows no significant difference between group P and group D, with a mean of 33 min in group P and 38.4 min in group D.

Onset of Action

Onset of action was assessed with the onset of signs of sedation end points, that is slurred speech and presence of ptosis (Verrill’s sign). The difference between the two groups was very significant with a mean of 4.2 min for group P and 6.1 min for group D (Table 1).

Table 1.

Onset of action

| Parameters | Diazepam (D) | Propofol (P) | Diff. between D&P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | ||

| Duration of surgery (min) | 26–48 | 38 ± 7.37 | 25–52 | 33.0 ± 8.52 | NS |

| Onset of action (min) | 3–11 | 6.1 ± 2.68 | 3–7 | 4.2 ± 1.23 | P < 0.05 |

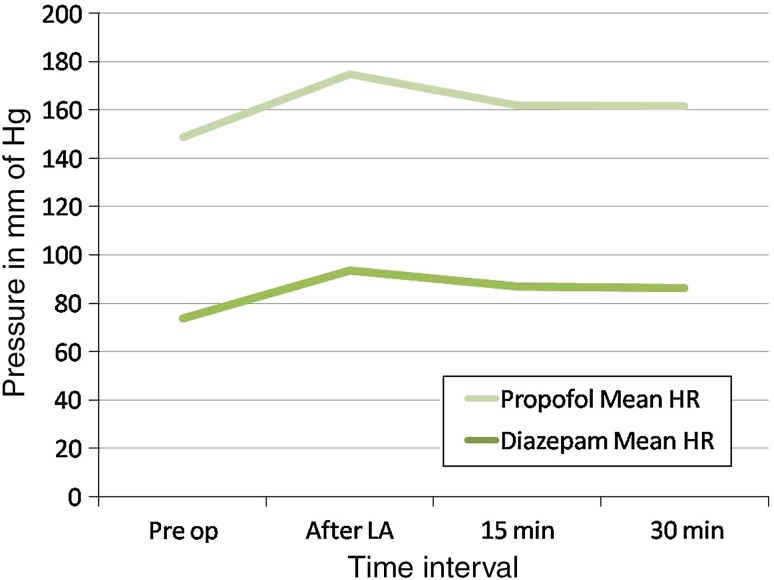

Heart Rate

An increase in heart rate was seen in both the groups but the increase in heart rate at all stages was significantly higher in group D patients as compared to those in group P. A sudden significant increase in heart rate was noticed in both the groups after administration of local anesthesia but the increase was more profound in group D (19 %) than group P (8 %). The intra-operative increased heart rate gradually returned to base line values in the recovery room in both the groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Heart Rate

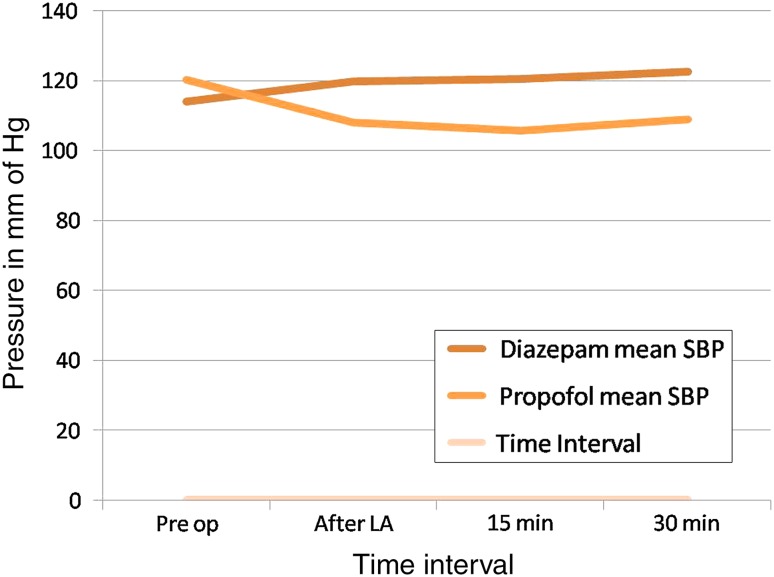

Blood Pressure

An increase in systolic pressure was observed in group D whereas a statistically significant decrease in systolic blood pressure was observed in group P throughout the procedure (Fig. 2). When results of both the groups were compared a statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups. In group P the percentage decrease ranged from 10 to 13 % and in group D the percentage increase ranged from 5 to 7.4 %.

Fig. 2.

Systolic Blood Pressure

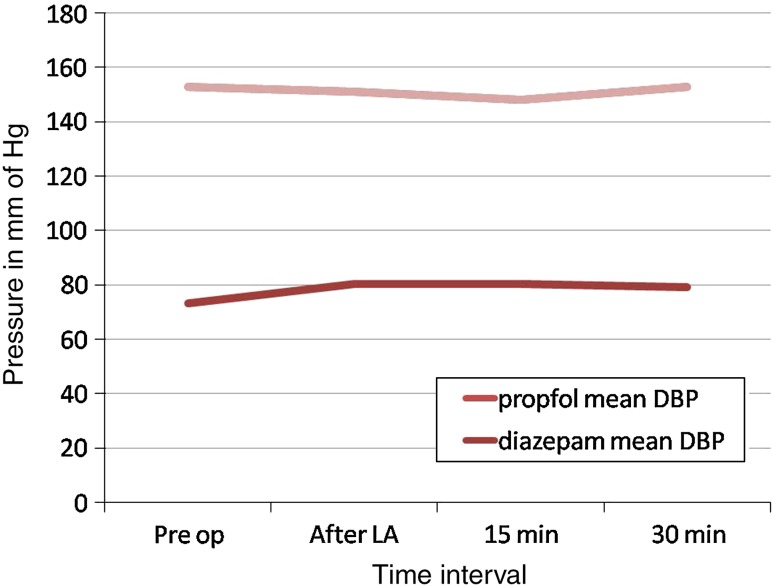

Similarly an increase in diastolic pressure ranging from 3.5 to 9.5 % in group D and a significant decrease in diastolic pressure ranging from 7 to 12 % was noticed in group P (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Diastolic Blood Pressure

In case of mean arterial pressure, a significant increase was observed in group D and a significant decrease in group P throughout the procedure. The difference between the two groups was also statistically significant.

In both the groups the systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressures gradually returned almost to baseline values at the discharge time.

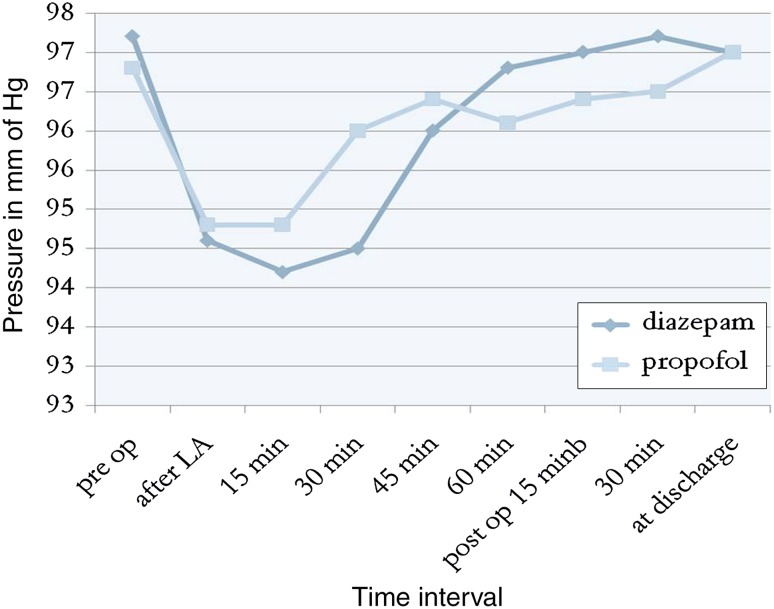

Oxygen Saturation

Oxygen saturation was measured from a pulse oximeter and showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups. Both the groups maintained significantly lower values than the baseline. In two instances oxygen saturation was reduced to 88 % from predrug values of 96 and 95 % respectively in group P. However no patients had any episode of apnoea which required emergency management (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Oxygen Saturation Key

Electrocardiogram (E.C.G.)

Arrhythmias of any kind were not noticed on the E.C.G. monitor lead II, in both the groups throughout the procedure.

Amnesic Effect

When the patients were questioned post-operatively, all the patients could remember venipuncture and therefore no retrograde amnesia was established in any of the two groups.

Anterograde amnesia in both the groups is shown in Table 2. From the data, it may be inferred that patients in group P experienced early and profound amnesia than the patients in group D. 80 % of patients in group P experienced profound amnesia for tactile and visual stimuli as compared to 10 % in group D.

Table 2.

Anterograde amnesia

| Procedure | Diazepam | Propofol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clearly | Faintly | Does not recall | Clearly | Faintly | Does not recall | |

| LA administration | 4(40) | 4(40) | 2(20) | 2(20) | 2(20) | 6(60) |

| Touch nose | 5(50) | 4(40) | 1(10) | 1(10) | 6(60) | 3(30) |

| Surgery | 3(30) | 5(20) | 2(20) | – | 3(30) | 7(70) |

| Tactile stimuli | 4(40) | 5(50) | 1(10) | – | 2(20) | 8(80) |

| Visual stimuli | 5(50) | 4(40) | 1(10) | – | 2(20) | 8(80) |

| Suture placement | 5(50) | 5(50) | – | 2(20) | 4(40) | 4(40) |

| Recovery room events | 8(80) | 2(20) | – | 10(100) | – | – |

| Going home | 10(100) | – | – | 10(100) | – | – |

From the checklist (Table 2) anterograde amnesia was evaluated as good, moderate and poor for each group. 60 % of the patients experienced good amnesia as compared to 10 % of patients in group D. The difference between the two groups is statistically significant (P < 0.02) suggesting a greater degree of intraoperative amnesia with group P as compared to group D.

Recovery Period

Post-operatively, all patients in both the groups were oriented to person, place and time. Recovery was measured from the last dose of the drug to the time when the patient could walk in a straight line without support. Vital signs were recorded post-operatively, which gradually returned close to pre drug baseline values during recovery.

The mean recovery period shows a statistically significant (P < 0.01) difference between the two groups with a mean of 33 min in group P and 99.5 min in group D, suggesting a significant faster recovery in group P patients as compared to group D patients.

Peg Board Test

Patients performance on Peg Board Test pre-operatively and post-operatively was assessed according to the difference from the baseline (Table 3). Peg Board Test showed that the psychomotor co-ordination was clearly affected in both the groups at 15 min post-operatively. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant at 30 and 60 min post-operatively with group P showing faster return of psychomotor co-ordination as compared to group D patients.

Table 3.

Peg Board Test scores

| Time interval | Diazepam | Propofol | Diff. between D&P | Significance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s) | Diff from Pre-op | % Change | Sig. | Mean (s) | Diff from Pre-op | % Change | Sig. | |||

| Pre-op | 19.0 ± 1.56 | – | – | – | 18.5 ± 1.27 | – | – | – | 0.5 | NS |

| Post-op. 15 min | 25.5 ± 2.68 | 6.5 | 34.2 | P < 0.001 | 23.1 ± 2.60 | 4.6 | 24.9 | P < 0.01 | 2.4 | NS |

| 30 min | 24.0 ± 2.91 | 5.0 | 26.3 | P < 0.001 | 20.9 ± 2.02 | 2.4 | 13.0 | P < 0.01 | 3.1 | P < 0.01 |

| 60 min | 22.1 ± 2.13 | 3.1 | 16.3 | P < 0.001 | 19.1 ± 1.45 | 0.6 | 3.2 | P < 0.02 | 3.0 | P < 0.01 |

| 90 min | 20.5 ± 2.22 | 1.5 | 7.9 | P < 0.001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 120 min | 20.0 ± 1.94 | 1.0 | 5.3 | P < 0.01 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| At discharge | 19.7 ± 1.57 | 0.7 | 3.7 | NS | 18.8 ± 1.03 | 0.3 | 1.6 | NS | 0.9 | NS |

Peg board test score almost returned to baseline score at the time of discharge of the patients in both the groups.

Patient Co-operation and Level of Sedation

Patient co-operation and level of sedation was assessed by grading on Ramsay Sedation Score. In group P, 60 % of the patients were co-operative and tranquil as compared to 10 % of the patients in group D and 50 % of the group D patients were anxious, agitated and restless as compared to 10 % of the patients in group P. The data suggests a higher degree of patient co-operation in group P patients as compared to group D patients.

Surgeon’s Convenience

Surgeon’s convenience was graded as excellent, good, moderate and poor. According to the surgeon 40 % of the patients in group P scored excellent, 50 % good and 10 % moderate whereas in group D, 20 % of the patients scored good, 50 % moderate and 30 % poor. The above results indicate the surgeon’s preference towards group P as compared to group D.

Side Effects

Pain on injection was present in 60 % of the patients in group P whereas 20 % of patients in group D had pain and burning sensation during injection. No incidence of post injection thrombophlebitits was reported in either of the groups. Headache was present in 30 % of the patients in group D during recovery period as compared to 10 % of the patients in group P. Talkativeness was observed in 20 % of the patients in group P whereas in group D 20 % of the patients reported dizziness and 10 % had nausea and vomiting (Table 4).

Table 4.

Side effects

| Side effects | Diazepam (no. of cases) | Propofol (no. of cases) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain on injection | 2 (20 %) | 6 (60 %) |

| Burning sensation on injection | 2 (20 %) | – |

| Headache | 3 (30 %) | 1 (10 %) |

| Dizziness | 2 (20 %) | – |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 (10 %) | – |

| Talkativeness | – | 2 (20 %) |

Discussion

Fear and anxiety about pain are common reasons for patients to delay dental care. Fear, apprehension, anesthesia and surgery are also accompanied by various and often harmful cardiovascular, metabolic and hormonal responses [17].

Conscious sedation in combination with local anesthesia has been used as a safe alternative to general anesthesia for control of peri-operative pain and anxiety in oral surgery [18].

Since the introduction of intravenous sedation by Pierre-Cyprien Ore of Bordeaux, France in 1872, various agents have been introduced to provide adequate analgesia, amnesia, anxiolysis and patient co-operation [12].

Diazepam was considered as a drug that could be easily titrated over a wide spectrum ranging from light sedation to hypnosis and had beneficial effects like fast onset of drowsiness, smooth sedation, better amnesia and faster mean recovery time [19]. Diazepam also has minimal effects on cardiovascular system and does not depress the respiratory response, except in high doses. Its main disadvantages are pain on injection in 30–80 % of cases, post injection thrombophlebitis, longer elimination half life and poor analgesic effect [20].

Propofol, an alkyl phenol, is a fast acting sedative hypnotic agent with a short duration of action, rapid recovery profile and low incidence of excitatory effects [8, 9]. Its side effects include pain on injection, hypotension and transient respiratory depression [5].

This study was undertaken to assess the usefulness of Propofol as a sedating agent in day care oral surgery in comparison with Diazepam in terms of onset of action, recovery, amnesia, patient co-operation, surgeon’s convenience and side effects.

In the present study, the mean age in group P was 22.6 years (SD ± 5.8) and 25.6 in group D (SD ± 5.7). The sex incidence, male: female ratio was 4:6 in group P and 7:3 in group D. Mean duration of surgery in group P was 33 min (SD ± 8.52) and group D 38.4 min (SD ± 7.3).

The onset of action varied significantly between Propofol and Diazepam groups with a mean of 4.2 min (SD ± 1.23) and 6.1 min (SD ± 2.6) respectively. Mann–Whitney U test was very significant (P < 0.01) showing faster onset of action with propofol. The onset of action of Propofol is similar to the observations made by Valtonen et al. [21].

A sudden increase in heart rate was noticed in both the groups after administration of local anesthesia, which can be attributed partly to the strength of adrenaline (1:80,000) used in local anesthetic solutions [22]. The rise in heart rate during the procedure can also be due to sympathetically induced increase in vasomotor tone as a result of waning of sedative effect of the drugs or due to peak surgical stimuli.

The mean heart rate values were lower throughout the procedure with propofol as compared to Diazepam and the result obtained is similar to the observations made by Valtonen et al. [21].

A significant decrease in systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressures was observed in group P. Reduction in arterial blood pressure with induction of Propofol has been well documented [5]. Marked reduction in arterial pressure can be attributed to the incremental bolus dose technique used for maintenance of sedation rather than continuous infusion technique. Increased bolus dose administration may produce variable plasma concentrations thereby increasing the episodes of hypotension.

An increase in arterial blood pressure was observed in group D throughout the procedure. Benzodiazepines generally known to have no significant effects on parameters like heart rate and blood pressure after local anesthesia can be attributed to the strength of adrenaline. The rise can also be partly due to sympathetically induced increase in vasomotor tone, as a result of waning of sedative effect of the drugs or due to peak surgical stimuli during the procedure [12].

The mean arterial pressures were lower throughout the procedure with Propofol as compared to Diazepam, which is in accordance with the study conducted by Valtonen et al. [21].

In our study, both the groups showed significant reduction in oxygen saturation. In two instances in group P the oxygen saturation reduced to 87 %, which can also be attributed to the incremental bolus administration of the drug for maintenance of sedation which may enhance the episodes of apnoea, similar to the observations made by Struys et al. [23] and Grounds et al. [24]. However, in our study the dose of both the drugs were given at a slow rate so that the episodes of apnoea did not exceed to the level where emergency intervention was required.

A lower rate of occurrence of arrhythmias during oral surgery with local anesthesia when combined with intravenous sedation was demonstrated.

Arrhythmias of any kind were not seen on the ECG in lead II in both the groups throughout the procedure.

Retrograde amnesia was not noted in any of the groups as all patients could remember venipuncture and pre-operative testing clearly.

In our study, the Propofol group exhibited anterograde amnesic properties clearly superior to those of Diazepam, which is an important consideration in the choice of a sedating agent for use during oral surgical procedures. This observation is similar to the study conducted by Valtonen et al. [21].

The mean recovery period shows that the mean recovery time of Group P is 33 min and of group D is 99.5 min. Diazepam when administered is known to produce prolonged recovery time i.e., 60–180 min,which is due to its long half life resulting from its pharmacologically active metabolites. The recovery period was significantly faster with Propofol as compared to Diazepam which results in earlier discharge of the patient [21].

Psychomotor performance after drug administration has been assayed by Peg Board Test. The validity of this test, as a measure of drug effect is that, drugs that depress the central nervous system act secondary to interrupt stimulus response integration [15].

In the present study Peg Board Test showed that the psychomotor coordination was clearly affected in both the groups 15 min post-operatively. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant at 30 and 60 min post-operatively where group P showed faster return of psychomotor co-ordination [21].

An absolute necessity for any oral surgical procedure is an unconditional patient co-operation. Patient co-operation and level of sedation was assessed on the Ramsay Sedation Score [16, 24]. Statistical analysis shows 60 % of the patients to be co-operative and tranquil in group P as compared to 10 % of the patients in group D. 50 % of the patients in group D were anxious, agitated and restless as compared to 10 % of the patients in group P, suggesting a higher degree of patient cooperation in group P as compared to group D.

Surgeon’s convenience is usually directly proportional to patient cooperation. 40 % of the patients scored excellent and 50 % good in group P, whereas none of the patients in group D scored excellent and only 30 % showed good, indicating a higher surgeon’s preference for group P.

Pain on injection was experienced by 60 % of the pateients in group P [21, 25] and 20 % of patients in group D as documented by Wood et al. [13], Mitchell et al. [26], Barklay et al. [27]. No incidence of thrombophlebitis was observed in any of the groups. Talkativeness was observed in 20 % of the patients in group P. Other side effects include headache (30 %) and dizziness (20 %) in group D patients.

Conclusion

The design of the present study permitted a qualitative comparison between the two intravenous sedative drugs, Diazepam and Propofol, to provide sedation in apprehensive and uncooperative patients undergoing day care oral surgical procedures.

Based on the parameters evaluated in the present study, we can conclude Propofol as a superior sedating agent compared to Diazepam, having rapid onset and predictability of action, profoundness of amnesia and a faster recovery period, offering advantages of early patient discharge and better patient compliance [28].

However, further extensive double blind studies over a larger population are required to accord Propofol as an ideal sedating agent in day care oral surgical procedures.

References

- 1.Vanderbijl P, Roelofse JA. Intravenous midazolam in oral surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:325–332. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(87)80154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarasin DS, Ghoneim NM (1996) Effect of sedation with midazolam or propofol on cognition and psychomotor functions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54:1187–1193 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wylie Report Report of the working party on training in dental anesthesia. Br Dent J. 1981;151:385–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigo MRC, Rosenquist JB. Conscious sedation with Propofol. Br Dent J. 1989;166:75–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White Paul F. Propofol pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics. Semin Anesth. 1988;7:4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guy J. The neuropharmacology of propofol. J Drug Dev. 1991;4:103–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cillo Joseph E, Buffalo NY. Propofol anaesthesia for outpatient oral maxillofacial surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path. 1999;87:530–538. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam HK, Briggs LP. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of ICI 35868 in man. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:97–103. doi: 10.1093/bja/55.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Doze A, Westphal LM, et al. Comparison of propofol with methohexital for outpatient anesthesia. Anaesth Analg. 1986;65:1189–1195. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198611000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logan MR, Duggan JE, et al. Single shot IV anesthesia for outpatient dental surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:179–183. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter James J, et al. Current theories about the mechanism of benzodiazepines and neuroleptic drugs. Anaesthesiology. 1981;54:66–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malamed Stanley F. Sedation: A guide to patient management. 1. St. Louis: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood N, Sheikh A, et al. Midazolam and Diazepam for minor oral surgery. Br Dent J. 1986;160:9–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grattidge P. Patient controlled sedation using Propofol in day surgery. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:683–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vickers MD. The measurement of recovery from anesthesia. Br J Anesth. 1965;37:296–302. doi: 10.1093/bja/37.5.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsay MA, Savege TM, et al. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone alphadolone. Br Medical J. 1974;2:656–659. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5920.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmondson H. Biochemical evidence of anxiety in dental patients. Br Med J. 1972;4:712. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5831.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett CR. Conscious sedation: an alternative to general anaesthesia. J Dent Res. 1984;63:832–833. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keilty SR, Blackwood S. Sedation for conservative dentistry. Br Dent J of Clin Pract. 1969;23:365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon HR, Tilton BE, et al. A comparison of the sedative and cardiopulmonary effects of Diazepam and Pentazocine premedication. Anaesth Analg. 1970;49:546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valtonen M, Saloen M, et al. Propofol infusion for sedation in outpatient oral surgery. A comparison with Diazepam. Anesthesia. 1989;44:730–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1989.tb09257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nusstein J, Berlin J et al (2004) Comparison of injection pain, heart rate increase, post injection pain of articaine and lidocaine in a primary intraligamentary injection administered with a computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery system. J Anesth 51:126–133 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Struys M, Versichelen L, et al. Comparison of computer controlled administration of Propofol with two manually controlled infusion techniques. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.002-az001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grounds RM, Lelor JM, et al. Propofol infusion for sedation in the intensive care unit. Preliminary report. Br Med J. 1987;294:397–400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6569.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eriksson M, Englesson S, et al. Effects of lignocaine and pH on Propofol induced pain. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:502–506. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell Paul F (1980) Diazepam associated thrombophlebitis. J Am Dent Assoc 101:492–495 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Barclay JK, Hunter KM, et al. Midazolam and Diazepam compared as sedatives for out patient surgery under local analgesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;59:349–355. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilbur K, Zed PJ. Is propofol an optimal agent for procedural sedation and rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department? CJEM. 2001;3(4):302–310. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]