Abstract

Objective

To describe labor patterns in women with a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) with normal neonatal outcomes.

Study Design

In a retrospective observational study at 12 U.S. centers (2002–2008), we examined time interval for each centimeter of cervical dilation and compared labor progression stratified by spontaneous or induced labor in 2,892 multiparous women with TOLAC (second delivery) and 56,301 nulliparous women at 37 0/7 to 41 6/7 weeks of gestation. Analyses were performed including women with intrapartum cesarean delivery, and then repeated limiting only to women who delivered vaginally.

Results

Labor was induced in 23.4% of TOLAC and 44.1% of nulliparous women (P<.001). Cesarean delivery rates were 57.7% in TOLAC versus 19.0% in nulliparous women (P<.001). Oxytocin was used in 52.4% of TOLAC versus 64.3% of nulliparous women with spontaneous labor (P<.001) and 89.8% of TOLAC versus 91.6% of nulliparous women with induced labor (P=.099); however, TOLAC had lower maximum doses of oxytocin compared to nulliparous women: median (90th percentile): 6 (18) mU/min versus 12 (28) mU/min, respectively (P<.001). Median (95th percentile) labor duration for TOLAC versus nulliparous women with spontaneous labor from 4–10cm was 0.9 (2.2) hours longer (P=.007). For women who entered labor spontaneously and achieved vaginal delivery, labor patterns for TOLAC were similar to nulliparous women. For induced labor, labor duration for TOLAC versus nulliparous women from 4–10cm was 1.5 (4.6) hours longer (P<.001). For women who achieved vaginal delivery, labor patterns were slower for induced TOLAC compared to nulliparous women.

Conclusions

Labor duration for TOLAC was slower compared to nulliparous labor, particularly for induced labor. By improved understanding of the rates of progress at different points in labor, this new information on labor curves in women undergoing TOLAC, particularly for induction, should help physicians when managing labor.

Keywords: first stage of labor, trial of labor after cesarean, TOLAC, VBAC, vaginal birth after cesarean

INTRODUCTION

Cesarean delivery accounted for 32.8% of deliveries in 2012.1 In a prior Consortium on Safe Labor study, the most common reason for cesarean was elective repeat due to a previous uterine scar, accounting for 30.9% of all cesarean deliveries.2 There has been a national interest in increasing the vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate in women with a prior low transverse cesarean delivery to decrease the overall cesarean rate. The rate of VBAC started to decline in 1996, prompting a 2010 consensus conference by the National Institutes of Health.3 After review of the available data, the conference concluded that VBAC was a safe option for many women with a prior low transverse cesarean delivery. A recent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) practice bulletin has revisited VBAC and emphasized the importance of discussing VBAC with all patients who meet criteria for it.4 Prior cesarean delivery may be a marker of dysfunctional labor, so it is important to understand labor patterns in subsequent deliveries. Exploring labor patterns among these women may be clinically useful for counseling as well as to guide clinical management during the course of labor among women attempting a VBAC.

Data on labor patterns for trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) are limited to single institutions with small numbers, with the older studies conducted prior to the use of modern statistical methods.5–8 In addition, labor patterns in women undergoing induction of labor with prior uterine scar have not been studied. The objectives of this study were to compare spontaneous and induced labor characteristics for women with normal neonatal outcomes undergoing TOLAC who had one prior cesarean and no vaginal deliveries to nulliparous women in labor, and also to compare the course of labor for women who achieved vaginal delivery (e.g. having a successful VBAC).

STUDY DESIGN

The Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL) was a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development multicenter collaborative study designed to characterize labor and delivery in a contemporary U.S. obstetrical clinical practice.2, 9 The CSL included 12 clinical centers (19 hospitals) spanning 9 ACOG districts from 2002 to 2008. Detailed information was obtained from electronic medical records on maternal demographics, medical history, reproductive and prenatal history, labor and delivery summary, postpartum and newborn information. Newborn records were linked to information from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Labor progression data including date and time of repeated cervical exams were extracted from the electronic labor database. Oxytocin data included date and start of medication, and starting and maximum doses. Data transferred from the clinical centers were mapped to predefined common categories for each variable at a data coordinating center. Data cleaning, inquiries, recoding and logic checking were performed. Validation of data was performed for four important outcome diagnoses: cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing, neonatal asphyxia, NICU admission for respiratory conditions, and shoulder dystocia. Data electronically transferred from the medical records were highly concordant with data that were hand abstracted from the records (greater than 95% for all except for one, 91.1% for clinical diagnosis of shoulder dystocia).2 Institutional review board approval was obtained at all participating institutions and the data coordinating center as listed in the Acknowledgement section. Since this study represented a retrospective review of electronic medical records, it was classified as exempt by the Office of Human Subjects Research (OHSR) at the National Institutes of Health.

There were 228,438 deliveries in the CSL. For this analysis, we limited it to woman’s first pregnancy in the dataset (n=208,695), singleton gestations (n=203,999), delivering between 37 0/7 and 41 6/7 weeks of gestation (n=178,582) with vertex presentation (154,894), and had either spontaneous or induced labor (n=141,919). Fetal anomalies (n=7,616) and antepartum stillbirths (n=160, were excluded (remaining n=134,143). We also excluded labor that resulted in uterine rupture (n=60) to describe labor patterns without this complication. We further limited the study sample to exclude neonates with a 5 minute Apgar score < 7, sustained a birth injury, or were admitted to the NICU (n=125,096) as was previously done in the primary CSL labor patterns study.9 There were 2,892 multiparous women (parity=1) undergoing TOLAC with one prior cesarean delivery and no prior vaginal deliveries and 56,301 nulliparous women who comprised the final study sample.

Statistical analysis

Demographics were compared between women undergoing TOLAC and nulliparous women using Chi-square test for categorical variables or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. A sub analysis of 6 hospitals where specific oxytocin dosing information was available was also performed to compare starting and maximum doses of oxytocin as well as cervical dilation at oxytocin start. Two analyses were conducted to compare labor progression. First, we examined the pattern of labor by investigating the relationship between duration of labor and cervical dilation only for women with a vaginal delivery. We limited the analysis to women with a vaginal delivery to first evaluate the labor patterns in women who achieved a successful VBAC and also to replicate the labor analysis performed in the original CSL paper.9 A repeated-measures regression with a polynomial function was used to model the curve of cervical dilation. Second, we performed an analysis comprised of all women attempting TOLAC, which included women with an intrapartum cesarean delivery, and examined the interval-censored time interval of cervical dilatation from one centimeter to the next by calculating median (95th percentile) traverse times (hour) for women undergoing TOLAC versus nulliparous women as previously described.10 P-values were obtained from a censored regression adjusting for maternal age, race, body mass index (BMI) at delivery, insurance, epidural use, and oxytocin. Multiple imputation was performed for missing admission BMI (n=10,174) and maternal age (n=71) using prepregnancy BMI, parity, race, insurance, smoking, diabetes, hypertension and site with the MICE approach in R, version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).11 The duration of second stage labor was compared by using a Cox regression model with the same covariates listed above for the interval censored models.12 The rest of the statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, US).

RESULTS

Compared to nulliparous women, women undergoing TOLAC were older, less likely to be white, and had higher prepregnancy BMI (P <.001 for these variables). (Table 1) Gestational age at delivery was slightly earlier for women undergoing TOLAC (39.1 versus 39.4 weeks, P <.001), but there were no clinically meaningful differences in median cervical dilation (3 cm), effacement (80%) or fetal station (−2) upon admission. Women undergoing TOLAC when compared to nulliparous women were less likely to be induced (23.4% versus 44.1%, P <.001), have an epidural (47.9% versus 58.6%, P <.001) and less likely to have oxytocin augmentation in spontaneous labor (52.4% versus 64.3%, P <.001) and induced labor (89.8% versus 91.6%, P <.001).

Table 1.

Maternal and obstetrical characteristics for singleton term pregnancies and normal neonatal outcomes for women with trial of labor after cesarean and nulliparous women.

| Characteristic | TOLAC* n=2,892 |

Nulliparous Women n=56,301 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 28.3 ± 5.7 | 24.9 ± 5.9 | <.001 |

| Race (%) | <.001 | ||

| White | 43.0 | 49.7 | |

| Black | 23.7 | 21.0 | |

| Hispanic | 20.3 | 16.7 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5.3 | 5.2 | |

| Other/Unknown | 7.6 | 7.4 | |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 26.5 ± 6.7 | 24.2 ± 5.6 | <.001 |

| Admission BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 31.9 ± 6.5 | 30.1 ± 5.9 | <.001 |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks (mean ± SD) | 39.1 ± 1.1 | 39.4 ± 1.3 | <.001 |

| Pre-existing diabetes (%) | 1.6 | 0.7 | <.001 |

| Gestational diabetes (%) | 4.9 | 3.6 | <.001 |

| Chronic hypertension (%) | 2.1 | 1.1 | <.001 |

| Gestational hypertension (%) | 1.8 | 3.7 | <.001 |

| Preeclampsia/HELLP (%) | 3.4 | 5.0 | <.001 |

| Eclampsia (%) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.439 |

| Cervical dilation at admission, cm - Median (10th, 90th percentile) | 3 (0.5, 6) | 3 (1, 6) | 0.004 |

| Cervical effacement at admission (%) - Median, % (10th, 90th percentiles) | 80 (30, 100) | 80 (50, 100) | <.001 |

| Station at admission (%) - Median (10th, 90th percentiles) | −2 (−3, 0) | −2 (−3, 0) | <.001 |

| Epidural (%) | 47.9 | 58.6 | <.001 |

| Induction (%) | 23.4 | 44.1 | <.001 |

| Oxytocin for spontaneous labor (%) | 52.4 | 64.3 | <.001 |

| Oxytocin for induced labor (%) | 89.8 | 91.6 | 0.099 |

| Cesarean delivery (%) | 57.7 | 19.0 | <.001 |

| Estimated Blood Loss, mL (mean ± SD) | 574 ± 273 | 426 ± 304 | <.001 |

Women (parity=1) with one prior cesarean delivery and no prior vaginal deliveries attempting vaginal birth after cesarean.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome; SD, standard deviation; TOLAC, trial of labor after cesarean

Term was defined as delivery between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation. Antepartum stillbirths, women with uterine rupture, and neonates with fetal anomalies, 5 minute Apgar score < 7, sustained a birth injury or were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit were excluded.

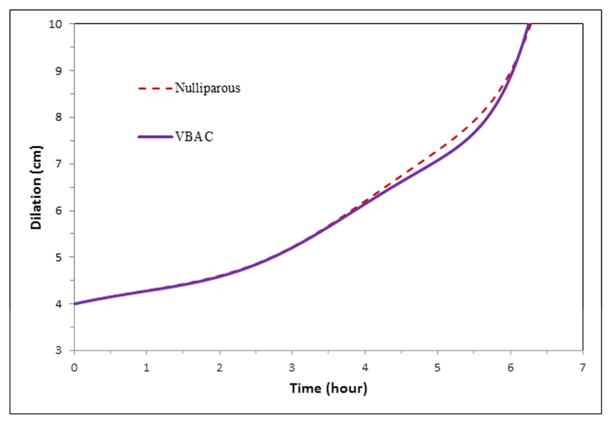

For women presenting in spontaneous labor who had vaginal delivery, labor patterns were similar for VBAC and nulliparous women. (Figure 1) In the full cohort including women who had an intrapartum cesarean delivery, duration of labor from 4 to 10 cm for women undergoing TOLAC overall was a median of 0.9 hours (54 minutes) longer, with 95th percentile difference of 2.2 hours longer, and significant differences from 4–5cm and 6–7 cm. (Table 2) Median second stage of labor was slightly shorter (0.1 hour, or 6 minutes) for women undergoing TOLAC, regardless of epidural status.

Figure 1. Mean labor curves for spontaneous onset of labor.

Mean labor curves in singleton term pregnancies with spontaneous onset of labor, vaginal delivery, and normal neonatal outcomes for women (parity=1) with one prior cesarean and successful vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) and nulliparous women. Term was defined as delivery between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation. Antepartum stillbirths, women with uterine rupture, and neonates with fetal anomalies, 5 minute Apgar score < 7, sustained a birth injury or were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit were excluded.

Table 2.

Duration of labor in hours for singleton term pregnancies with spontaneous onset of labor and normal neonatal outcomes for women with trial of labor after cesarean and nulliparous women.

| Interval (cm) | TOLAC* (Hours) Median (95th percentile) |

Nulliparous Women (Hours) Median (95th percentile) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4–5 | 1.8 (12.7) | 1.5 (8.9) | <.001 |

| 5–6 | 1.0 (5.1) | 0.9 (4.5) | .085 |

| 6–7 | 0.8 (4.3) | 0.7 (2.9) | <.001 |

| 7–8 | 0.6 (2.2) | 0.5 (2.0) | .573 |

| 8–9 | 0.5 (1.5) | 0.5 (1.7) | .622 |

| 9–10 | 0.5 (1.9) | 0.5 (2.0) | .376 |

| 4–10 | 7.4 (28.0) | 6.5 (25.8) | .007 |

|

| |||

| Second stage with epidural anesthesia | 1.0 (3.8) | 1.1 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Second stage without epidural anesthesia | 0.6 (2.8) | 0.7 (3.1) | 0.006 |

Women (parity=1) with one prior cesarean delivery and no prior vaginal deliveries attempting vaginal birth after cesarean.

Abbreviations: cm, centimeter; TOLAC, trial of labor after cesarean

Term was defined as delivery between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation. Antepartum stillbirths, women with uterine rupture, and neonates with fetal anomalies, 5 minute Apgar score < 7, sustained a birth injury or were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit were excluded. Adjusted for maternal age, race, body mass index at delivery, insurance, epidural use and oxytocin.

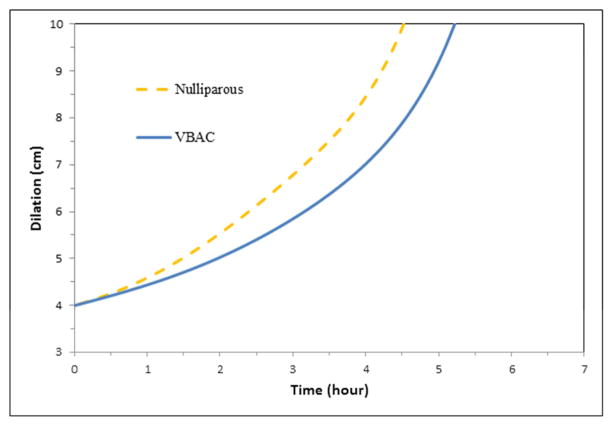

For women with induction of labor who had vaginal delivery, labor was slower for VBAC compared to nulliparous women. (Figure 2) In the full cohort including women who had an intrapartum cesarean delivery, duration of labor from 4 to 10 cm for women undergoing TOLAC overall was a median of 1.5 hours (90 minutes) longer, with 95th percentile difference of 4.6 hours longer, and significant differences prior to 8 cm. (Table 3) There was no difference in median second stage of labor with induction for women undergoing TOLAC compared to nulliparous women.

Figure 2. Mean labor curves for induced labor.

Mean labor curves in singleton term pregnancies with induction of labor, vaginal delivery, and normal neonatal outcomes for women (parity=1) with one prior cesarean and successful vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) and nulliparous women. Term was defined as delivery between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation. Antepartum stillbirths, women with uterine rupture, and neonates with fetal anomalies, 5 minute Apgar score < 7, sustained a birth injury or were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit were excluded.

Table 3.

Duration of labor in hours for singleton term pregnancies with induction of labor and normal neonatal outcomes for women with trial of labor after cesarean and nulliparous women.

| Interval (cm) | TOLAC* (Hours) Median (95th percentile) |

Nulliparous Women (Hours) Median (95th percentile) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4–5 | 1.7 (10.1) | 1.3 (8.0) | .098 |

| 5–6 | 1.1 (6.4) | 0.8 (4.2) | .002 |

| 6–7 | 0.8 (4.1) | 0.6 (2.4) | .0003 |

| 7–8 | 0.6 (2.5) | 0.5 (1.7) | .005 |

| 8–9 | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.5) | .664 |

| 9–10 | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.8) | .124 |

| 4–10 | 6.7 (26.2) | 5.2 (21.6) | .008 |

|

| |||

| Second stage with epidural anesthesia | 1.1 (3.5) | 1.1 (3.7) | 0.523 |

| Second stage without epidural anesthesia | 0.7 (2.6) | 0.7 (3.4) | 0.907 |

Women (parity=1) with one prior cesarean delivery and no prior vaginal deliveries attempting vaginal birth after cesarean.

Abbreviations: cm, centimeter; TOLAC, trial of labor after cesarean

Term was defined as delivery between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation. Antepartum stillbirths, women with uterine rupture, and neonates with fetal anomalies, 5 minute Apgar score < 7, sustained a birth injury or were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit were excluded. Adjusted for maternal age, race, body mass index at delivery, insurance, epidural use and oxytocin.

In a sub analysis of 6 hospitals (363 women undergoing TOLAC and 17,993 nulliparous women) where specific oxytocin dosing information was available, oxytocin was started at similar cervical dilation for both groups: median (10th, 90th percentiles) were 3 (0.5, 7) cm for women undergoing TOLAC and 3 (1, 7) cm for nulliparous women. However, women undergoing TOLAC were more likely to start at lower oxytocin doses compared to nulliparous women: 1, 2 or 4 milliunits per minute for women undergoing TOLAC were 41.1%, 43.5%, and 15.4%, respectively, and for nulliparous women 16.6%, 41.7%, and 41.8%, respectively (P <.001). In addition, women undergoing TOLAC had lower maximum doses of oxytocin compared to nulliparous women: median (90th percentile) for women undergoing TOLAC was 6 (18) milliunits per minute versus 12 (28) milliunits per minute for nulliparous women (P <.001). We adjusted for any oxytocin use in the duration of labor in hours (Tables 2 and 3) and the duration of labor between the two groups remained statistically significant. To try to address whether differences in oxytocin management may have been the reason for longer labor, we repeated the analysis in Tables 2 and 3 for the 4–10cm interval regression adjusting for starting dose and maximum dose of oxytocin. For spontaneous labor, the labor times were still longer for TOLAC versus nulliparous labor (4–10cm 7.1 (26.6) versus 5.9 (22.3) hours, respectively), but the differences were no longer statistically significant (P =.244). However, the differences remained for induced labor (4–10cm TOLAC versus nulliparous 6.2 (23.2) versus 4.8 (19.2) hours, respectively, P= .042).

COMMENT

In this large, U.S. multicenter observational study of term, vertex, singleton gestations with normal neonatal outcomes, duration of labor for women with one prior cesarean and no prior vaginal births undergoing TOLAC was slightly slower than nulliparous women in spontaneous labor. When all spontaneously labored women were examined, including those with an intrapartum cesarean delivery, the duration of labor was significantly slower prior to 7cm dilation. For the subgroup of women presenting in spontaneous labor who achieved vaginal delivery, the duration of labor was similar for VBAC and nulliparous women. Induced labor was significantly slower for women undergoing TOLAC prior to 8 cm.

The findings from our large cohort confirm the findings of a smaller single center study of 140 women undergoing TOLAC where women in spontaneous labor without oxytocin augmentation had similar labor patterns compared to women without a prior cesarean delivery.6 However, that study combined nulliparous and multiparous women, whereas we used nulliparous women which is the more appropriate comparison group because women who have had a previous spontaneous vaginal delivery have a different pattern of labor, specifically that they are more likely to progress faster after 6 cm cervical dilation.9 Our findings also confirm smaller, older studies that found women undergoing TOLAC without a previous vaginal delivery had similar or slightly longer labor compared to nulliparous women, although they studied overall length and not specific patterns of labor.5, 7, 8 Furthermore, labor that requires oxytocin may be different. Given the large increase in deliveries with oxytocin use in modern obstetrics, we were able to take that variable into account as well as other factors including increasing maternal BMI and epidural use which are known to be associated with longer labor duration.13–15 Our finding that induced labor was longer in women undergoing TOLAC compared to nulliparous women is novel.

A limitation of our study is the relatively high cesarean delivery rate in TOLAC compared to nulliparous women which may result in selection bias due to intrapartum censoring. For women who entered labor spontaneously, only 63.2% of women undergoing TOLAC were still in labor at 6cm cervical dilation compared to 90.5% of nulliparous women. For women who were induced, 65.1% of women undergoing TOLAC were still in labor at 6cm cervical dilation compared to 77.5% of nulliparous women. It is difficult to know the impact of intrapartum censoring on the labor curves and traverse times. Labor trajectories were presented only for women who delivered vaginally in order to evaluate the labor patterns in women who achieved a successful VBAC and it is possible that the censoring may have affected the entire curve. For traverse times, the active phase may have been more impacted, particularly for spontaneous labor. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that women undergoing TOLAC had a higher proportion of underlying labor disorders. However, labor dysfunction in women with prior cesarean may be less likely given that lower starting and maximum doses of oxytocin were used in women undergoing TOLAC which could explain the longer duration of labor observed in TOLAC. It is difficult to directly answer the question of whether differences in oxytocin management are the sole reason for longer labor in a retrospective study. There was no standard protocol for oxytocin as this study was observational, so starting doses and increases in the rate were performed at the discretion of the managing clinicians. The study did not collect information on institution specific protocols for oxytocin. Our findings that differences between total duration of the first stage for spontaneous labor were no longer statistically significant for women undergoing TOLAC after adjusting for both the starting and maximum doses of oxytocin suggests that longer labor duration for TOLAC may in part be explained by more conservative use of oxytocin.

It also would be interesting to know if labor patterns for women undergoing TOLAC differed based on the indication for or the last cervical dilation recorded for the prior cesarean delivery; however, the CSL study did not collect this information. Our data might only be representative of hospitals where there is a certain “culture” among physician or systems regarding TOLAC rather than labor patterns by themselves, but the major strength of our study is the large number of women analyzed and the inclusion of multiple institutions across the U.S.

In summary, for all women undergoing TOLAC, women who spontaneously entered labor had slightly slower progress prior to 7 cm dilation and women who were induced had slower progress prior to 8 cm compared to nulliparous women. Subsequently, labor progressed similarly after 7 cm and 8 cm respectively for both spontaneous and induced laboring women undergoing a trial of labor compared to nulliparous women. By improved understanding of the appropriate rates of progress at different points in labor, this new information on labor curves in women undergoing TOLAC, particularly for induced labor, should help physicians when managing labor.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The Consortium on Safe Labor was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, through Contract No. HHSN267200603425C.

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE: The funding source had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication (although the manuscript did receive clearance for submission for publication).

Institutions involved in the Consortium include, in alphabetical order: Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Burnes Allen Research Center, Los Angeles, CA; Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE; Georgetown University Hospital, MedStar Health, Washington, DC; Indiana University Clarian Health, Indianapolis, IN; Intermountain Healthcare and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY; MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.; Summa Health System, Akron City Hospital, Akron, OH; The EMMES Corporation, Rockville MD (Data Coordinating Center); University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; University of Miami, Miami, FL; and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest.

DISCLAIMER: Drs. Grantz, Troendle and Reddy are employees of the federal government; please see accompanying cover sheet. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this manuscript, which does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the NICHD.

PAPER PRESENTATION INFORMATION: This research was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiologic Research and Annual Society for Epidemiologic Research Meeting, Seattle, WA, June 24, 2014.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Branch DW, Burkman R, et al. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:326 e1–26 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development conference statement: vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights March 8–10, 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1279–95. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e459e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:450–63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harlass FE, Duff P. The duration of labor in primiparas undergoing vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graseck AS, Odibo AO, Tuuli M, Roehl KA, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Normal first stage of labor in women undergoing trial of labor after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:732–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824c096c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chazotte C, Madden R, Cohen WR. Labor patterns in women with previous cesareans. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:350–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faranesh R, Salim R. Labor progress among women attempting a trial of labor after cesarean. Do they have their own rules? Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011;90:1386–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Landy HJ, Branch DW, Burkman R, Haberman S, Gregory KD, et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1281–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Troendle JF, Yancey MK. Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:824–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972:187–220. Series B. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laughon SK, Branch DW, Beaver J, Zhang J. Changes in labor patterns over 50 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:419, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kominiarek MA, Zhang J, Vanveldhuisen P, Troendle J, Beaver J, Hibbard JU. Contemporary labor patterns: the impact of maternal body mass index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:244, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 36. Obstetric analgesia and anesthesia. 2002 [Google Scholar]