Abstract

Both neuronal acetylcholine and nonneuronal acetylcholine have been demonstrated to modulate inflammatory responses. Studies investigating the role of acetylcholine in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections have revealed contradictory findings with regard to disease outcome. At present, the role of acetylcholine in the pathogenesis of fungal infections is unknown. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether acetylcholine plays a role in fungal biofilm formation and the pathogenesis of Candida albicans infection. The effect of acetylcholine on C. albicans biofilm formation and metabolism in vitro was assessed using a crystal violet assay and phenotypic microarray analysis. Its effect on the outcome of a C. albicans infection, fungal burden, and biofilm formation were investigated in vivo using a Galleria mellonella infection model. In addition, its effect on modulation of host immunity to C. albicans infection was also determined in vivo using hemocyte counts, cytospin analysis, larval histology, lysozyme assays, hemolytic assays, and real-time PCR. Acetylcholine was shown to have the ability to inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. In addition, acetylcholine protected G. mellonella larvae from C. albicans infection mortality. The in vivo protection occurred through acetylcholine enhancing the function of hemocytes while at the same time inhibiting C. albicans biofilm formation. Furthermore, acetylcholine also inhibited inflammation-induced damage to internal organs. This is the first demonstration of a role for acetylcholine in protection against fungal infections, in addition to being the first report that this molecule can inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation. Therefore, acetylcholine has the capacity to modulate complex host-fungal interactions and plays a role in dictating the pathogenesis of fungal infections.

INTRODUCTION

Bloodstream infections caused by Candida species remain a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly within the immunocompromised population (1, 2). Candida albicans is an opportunistic pathogen that causes both superficial and systemic infections and is the main causative organism responsible for systemic candidiasis. Virulence factors that contribute to C. albicans pathogenicity include hypha formation, the expression of cell surface adhesins and invasins, and the development of biofilms (3). If untreated, a progressive C. albicans infection can lead to a dysregulated host inflammatory response that damages infected organs and leads to sepsis (4).

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway regulates immune responses to pathogens and is mediated by acetylcholine (ACh) (5). ACh released from efferent vagus nerve terminals interacts with the alpha 7 nicotinic receptor (α7nAChR) on proximal immune cells, resulting in downregulated localized immune responses. In addition, the efferent vagus nerve interacts with the splenic nerve to activate a unique ACh-producing memory phenotype T-cell population that can propagate ACh-mediated immunoregulation throughout the body (6). Furthermore, ACh is produced by numerous cells outside of neural networks, and nonneuronal ACh can also play a vital role in immune regulation through its cytotransmitter capabilities (7, 8).

Investigations into the role of the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway” in bacterial infections have revealed contradictory findings. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuated systemic inflammatory responses to bacterial endotoxin (5), and ACh attenuated endotoxin-induced release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF] and interleukin-1β [IL-1β]) but not anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) from macrophages (9). Furthermore, α7nAChR−/− mice infected with Escherichia coli developed more severe lung injury and had higher mortality rates than α7nAChR+/+ mice (10), and α7nAChR activation attenuated systemic inflammation in a polymicrobial abdominal sepsis model (11). In contrast, activation of the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway” had a detrimental effect on disease outcome in mouse models of E. coli-induced peritonitis (12) and pneumonia (13), as well as stroke-induced Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection (14). Therefore, the role ACh plays in the pathogenesis of bacterial disease depends on the site of infection and etiological agent. Furthermore, ACh synthesis has also been demonstrated in bacteria and fungi (15, 16). Cholinergic communication and regulation have been established to exist in these primitive unicellular organisms (15, 17). However, the receptors that mediate the response of microorganisms to ACh are not well characterized. Nevertheless, the role that host-derived ACh plays in modulating the growth and pathogenicity of microorganisms is unknown.

To date, no study has investigated the role of ACh in fungal infections, and the functional relationship between ACh and C. albicans biofilm formation and pathogenicity remains to be determined. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the effect of ACh on C. albicans growth and biofilm formation, as well as the role of ACh in modulating host innate immune responses during C. albicans infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Candida albicans culture.

Candida albicans SC5314 was subcultured onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SAB) (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) and stored at 4°C until required. For the experiments described, C. albicans was propagated in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom), washed by centrifugation, and resuspended in either yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) or RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom) to the desired concentration, as described previously (18).

Crystal violet assay and phenotypic microarray analysis.

Biofilm biomass of C. albicans cultured in RPMI for 24 h was quantified using the crystal violet assay, as previously described (18). Real-time cellular metabolic activity (respiration) was evaluated using phenotypic microarray (PM) analysis as previously described (19). Briefly, a suspension of C. albicans was adjusted to a transmittance of 62% (∼5 × 106 cells · ml−1) using a turbidimeter. Cell suspensions for the inoculums were then prepared in IFY buffer (Biolog, Hayward, CA), and the final volume was adjusted to 3 ml using reverse osmosis (RO) sterile distilled water. Ninety microliters of this cell suspension was then inoculated into each well of a Biolog 96-well plate (Biolog). Anaerobic conditions were generated by placing each plate into a PM gas bag (Biolog) and vacuum packed using an Audion VMS43 vacuum chamber (Audion Elektro BV, Netherlands). An OmniLog reader (Biolog) was used to photograph the plates at 15-min intervals to measure dye conversion, and the pixel intensity in each well was then converted to a signal value reflecting cell metabolic output.

Galleria mellonella killing assay.

The pathogenicity of C. albicans, in the presence and absence of ACh, was assessed using the G. mellonella killing assay (20, 21). Sixth-instar G. mellonella larvae (Livefoods Direct, Ltd., United Kingdom) with a body weight of between 200 to 300 mg were used in the study. Larvae were inoculated into the hemocoel with C. albicans (5 × 105 cells/larva), in the presence and absence of ACh (50 μg/larva), through the hindmost proleg, using a 50-μl Hamilton syringe with a 26-gauge needle. In addition, larvae inoculated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and ACh alone (50 μg/larva) were included for control purposes. For each experiment, 10 larvae were inoculated for each experimental group. The inoculated larvae were placed in sterile petri dishes and incubated at 37°C, and the number of dead larvae was scored daily. A larva was considered dead when it displayed no movement in response to touch together with a dark discoloration of the cuticle. The experiment was repeated on 3 independent occasions.

RNA and DNA extraction.

Larvae were inoculated as described above. At both 4 h and 24 h postinfection, 3 larvae from each experimental group were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a powder by mortar and pestle in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). The samples were further homogenized using a bead beater, and RNA was extracted as described previously (18). To extract DNA from the same sample, 250 μl back extraction buffer (4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 50 mM sodium citrate, 1 M Tris [pH 8.0]) was added to the phenol- and interphase, and the mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The upper phase was removed, and an equal volume of 100% isopropanol was added, after which the samples were incubated overnight at −80°C. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellets were washed 3 times with 70% ethanol. DNA was eluted in a final volume of 50 μl Tris EDTA (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). The experiment was repeated on 3 independent occasions.

Gene expression analysis.

RNA was quantified and quality assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Loughborough, United Kingdom). cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng of extracted RNA using a Life Technologies high-capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom) in a MyCycler PCR machine (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom), following the manufacturer's instructions. All primers used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) studies are shown in Table 1. The cycling conditions consisted of 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate using an MxProP qPCR machine and MxProP 3000 software (Stratagene, Amsterdam, Netherlands). No-reverse transcriptase (no-RT) and no-template controls were included. Gene expression was calculated by the threshold cycle (ΔCT) method (22).

TABLE 1.

Real-time PCR primers used in this study

| Gene or protein | Primer |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Sequence (5′→3′) | ||

| C. albicans | |||

| ALS3 | Forward | CAACTTGGGTTATTGAAACAAAAACA | 21 |

| Reverse | AGAAACAGAAACCCAAGAACAACCT | ||

| HWP1 | Forward | GCTCAACTTATTGCTATCGCTTATTACA | 21 |

| Reverse | GACCGTCTACCTGTGGGACAGT | ||

| ACT1 | Forward | AAGAATTGATTTGGCTGGTAGAGA | 21 |

| Reverse | TGGCAGAAGATTGAGAAGAAGTTT | ||

| 18S | Forward | CTCGTAGTTGAACCTTGGGC | Unpublished |

| Reverse | GGCCTGCTTTGAACACTCTA | ||

| G. mellonella | |||

| Gallerimycin | Forward | GAAGATCGCTTTCATAGTCGC | 45 |

| Reverse | TACTCCTGCAGTTAGCAATGC | ||

| Galiomicin | Forward | CCTCTGATTGCAATGCTGAGTG | 45 |

| Reverse | GCTGCCAAGTTAGTCAACAGG | ||

| β-Actin | Forward | GGGACGATATGGAGAAGATCTG | 45 |

| Reverse | CACGCTCTGTGAGGATCTTC | ||

Fungal burden.

DNA was quantified and quality assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Loughborough, United Kingdom). Colony-forming equivalents (CFE) of C. albicans were determined by 18S real-time PCR as described previously (23). The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate using an MxProP qPCR machine and MxProP 3000 software (Stratagene, Amsterdam, Netherlands). No-template controls were included. An analysis of nucleic acid extracted from serially titrated C. albicans was run in conjunction with each set of samples to quantify the fungal burden.

Hemocyte count.

Larvae were inoculated as described previously. However, to ensure the larvae survived for >72 h, a lower inoculum of C. albicans (1 × 105 cells/larvae) was used. At 24, 48, and 72 h postinoculation, 3 randomly selected larvae were bled and the hemolymph was pooled into a prechilled microcentrifuge tube containing a few granules of N-phenylthiourea (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent melanization (24). The total hemolymph volume was measured. Hemocytes were recovered by centrifugation (1,500 × g for 3 min) and resuspended in 100 μl of trypan blue (0.02% in PBS). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and viable hemocytes were enumerated using a Neubauer hemocytometer. The experiment was repeated on 3 independent occasions.

Cytospin assay.

Larvae were inoculated for hemocyte counts as described above. At 24, 48, and 72 h postinoculation, 100 μl of circulating hemolymph was extracted from 3 randomly selected larvae in each experimental group and diluted 1:1 in PBS prior to cytocentrifugation at 600 rpm for 5 min. Cytospin slides were fixed with Cytofix and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Image acquisition was performed by the NanoZoomer-XR C12000 series (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The experiment was repeated on 3 independent occasions.

Larval histology.

After hemolymph extraction, the same larvae were processed for histology as previously described (25). Briefly, the larvae were inoculated with buffered formalin and processed by means of transverse-cut serial sections. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS), and Giemsa stain, and examined by a technician and a pathologist. Image acquisition was performed by the NanoZoomer-XR C12000 series (Hamamatsu Photonics, Tokyo, Japan). The experiment was repeated on 3 independent occasions.

Lysozyme assay.

The lysozyme assay was performed following a modification of the method described by Shugar (26). Briefly, the hemolymph of 3 randomly selected larvae from each experimental group was collected on ice, and the weight was ascertained prior to dilution by addition of 50 μl of 66 mM potassium phosphate buffer (PPB), pH 6.24, at 25°C. The suspension was then centrifuged, and hemocytes were separated for enumeration using a Neubauer hemocytometer. Twenty-five microliters of the remaining hemolymph was then added to a suspension of Micrococcus lysodeikticus at 0.01% (wt/vol) in 66 mM PPB, and the reduction in turbidity was measured at 450 nm every 5 min. The hemolymph lysozyme concentration was calculated as follows: U/ml = [1,000 (ΔA450 test − ΔA450 blank)/min]/[sample (ml) × dilution]. The lysozyme concentration was then adjusted for the number of hemocytes. The experiment was repeated on 3 independent occasions.

Hemolytic (gallysin) assay.

The ability of hemolymph (gallysins) to lyse sheep red blood cells (RBC) was determined using a modification of the method described by Beresford et al. (27). Briefly, packed sheep RBC in Alsever's solution were centrifuged and washed in glycerol–Veronal-buffered saline at pH 7.4. (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). The cells were then suspended to 108 cells/ml in dextrose–glycerol–Veronal-buffered saline. Serial dilutions of hemolymph (collected as described above) starting with 1 μl of hemolymph diluted in a total of 100 μl of dextrose–glycerol–Veronal-buffered saline were combined with 100 μl of sheep red blood cells and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. After incubation, the samples were placed on ice, 2 ml saline was added, and the supernatant was centrifuged. The proportion of cells lysed by each dilution was compared to that in a negative control containing no hemolymph and a positive control in which all of the cells were lysed by the addition of 2 ml water. From this, hemolytic units were determined as follows: no. of hemolytic units/RBC = −ln[1 − (% lysis/100)]. The experiment was performed using hemolymph from 3 larvae in each experimental group and repeated on 3 independent occasions.

Statistical analysis.

Graph production, data distribution, and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 4; La Jolla, CA). After ensuring the data conformed to a normal distribution, before and after data transformation, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t tests were used to investigate significant differences between independent groups. The G. mellonella survival curve was analyzed using a log rank test. In the case of the gallysin assay, the slopes of each titration were surrogates for average values. A Bonferroni correction was applied to all P values to account for multiple comparisons of the data sets. Student t tests were used to measure statistical differences between two independent groups assessed in gene expression studies. Statistical significance was achieved if P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Acetylcholine inhibits Candida albicans biofilm formation in vitro.

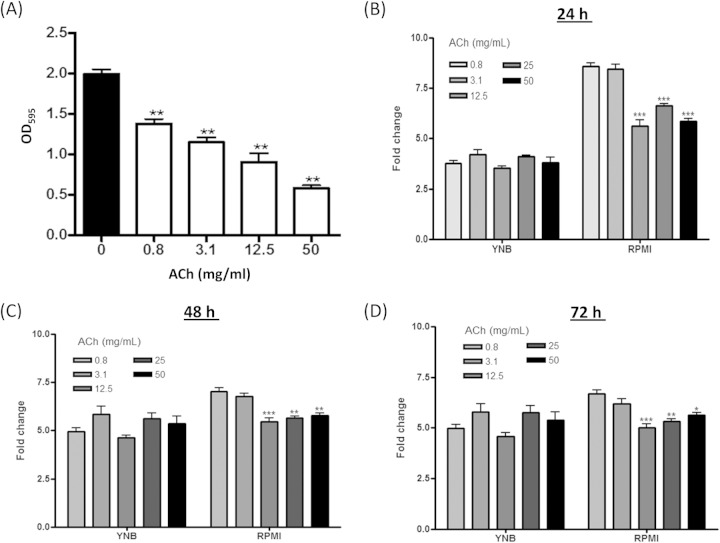

C. albicans biofilm formation has been increasingly recognized as a key mechanism of growth and survival in the host (3). Therefore, we initially investigated whether ACh had an impact on C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro. Crystal violet assays revealed a dose-dependent decrease in C. albicans biofilm biomass when cultured in RPMI (hypha-inducing medium) plus ACh compared to RPMI alone (Fig. 1A). A maximum 70.6% (P < 0.01) reduction in biomass was observed with 50 mg/ml of ACh, followed by 54.5% (P < 0.01), 42% (P < 0.01), and 30.7% (P < 0.01) reductions with 12.5, 3.1, and 0.8 mg/ml of ACh, respectively.

FIG 1.

Effects of acetylcholine on Candida albicans biofilm formation and metabolic activity in vitro. (A) Crystal violet assessment of C. albicans biomass after 24 h of growth in RPMI 1640 containing different concentrations of ACh (0 to 50 mg/liter). (B, C, and D) Graphical representations of phenotypic microarray analysis of C. albicans respiration during culture in RPMI and YNB for 24 h (B), 48 h (C), and 72 h (D) in the presence of different concentrations of ACh (0 to 50 mg/liter). All data are derived from triplicates of each condition performed in 3 independent experiments (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

To further investigate the impact of ACh on C. albicans phenotype, cellular respiration was assessed by phenotypic microarray (PM) analysis over a 72-h period when cultured in RPMI or YNB (non-hypha-inducing medium) ± ACh. The raw data for the PM analysis are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Graphical representations of the PM analysis revealed that there was no significant effect on C. albicans cellular respiration at 24 h (Fig. 1B), 48 h (Fig. 1C), or 72 h (Fig. 1D) when cultured in YNB with concentrations of ACh ranging from 0.8 to 50 mg/ml. In contrast, significant reductions in cellular respiration were observed when C. albicans was cultured in RPMI with 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/ml ACh at 24 h (Fig. 1B), 48 h (Fig. 1C), or 72 h (Fig. 1D) (all P values of <0.05). However, as changes in cellular respiration are associated with biofilm formation, this phenomenon could be accredited to the inhibition of biofilm formation demonstrated in Fig. 1A. Indeed, none of the concentrations of ACh used in this study were found to be cytotoxic to C. albicans when cultured in RPMI or YNB (data not shown).

Collectively, these data suggest that ACh is not fungicidal at the concentrations used in this study and instead can inhibit the ability of C. albicans to form biofilms in vitro.

Acetylcholine prolongs the survival of Candida albicans-infected Galleria mellonella larvae and reduces fungal burden.

Biofilm formation is associated with C. albicans pathogenicity (3). Therefore, the effect of ACh on C. albicans pathogenicity in vivo was investigated using a G. mellonella killing assay.

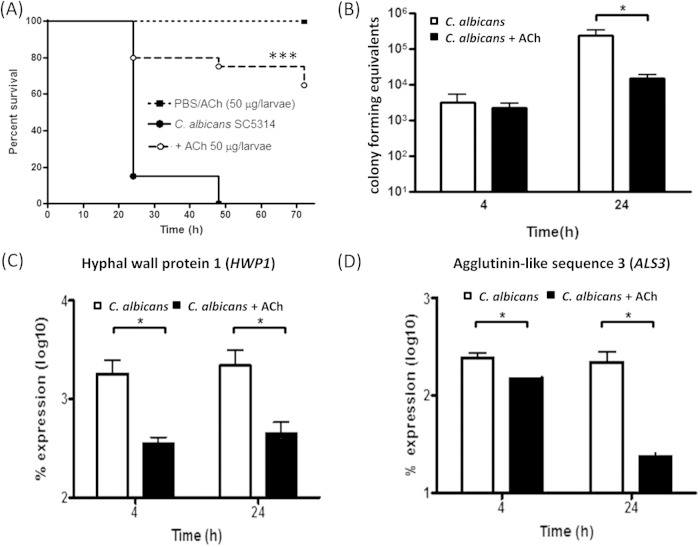

Inoculation of larvae with C. albicans was shown to kill >80% within 24 h (P < 0.001) and 100% within 48 h (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Conversely, larvae treated with C. albicans plus ACh (50 μg/larva) exhibited only 25% (P < 0.05) mortality within 48 h, and >60% remained alive after 72 h (Fig. 2A). The log rank test revealed a statistically significant difference in survival of larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh in comparison to larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone (P < 0.001). Control larvae, injected with PBS or ACh (50 μg/larva) alone, exhibited 0% mortality at 72 h (Fig. 2A). Therefore, these data suggest that ACh protects G. mellonella larvae from C. albicans-induced mortality.

FIG 2.

Effects of acetylcholine on survival of Galleria mellonella larvae after Candida albicans infection and the ability of Candida albicans to form a biofilm in vivo. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot showing the effect of ACh on the survival of Candida albicans-infected larvae. The data are derived from three independent experiments with groups of 10 larvae (n = 30). ***, P < 0.001, as determined by the log rank test in comparison to larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone. (B) Real-time PCR determination of the effects of ACh on larval fungal burden as determined by colony-forming equivalents (CFE). Data are derived from 3 larvae from each experimental group from 3 independent experiments (n = 9). (C and D) Real-time PCR determination of the effects of ACh on expression of key Candida albicans genes involved in dimorphic switching in vivo: hyphal cell wall protein 1 gene HWP1 (C) and agglutinin-like sequence 3 gene ALS3 (D). Data are derived from 3 larvae from each experimental group from 3 independent experiments (n = 9). *, P < 0.05.

To determine whether this protection against mortality was due to the effect of ACh on fungal growth in vivo, fungal burden was assessed using a qPCR-based assay. Four hours postinoculation, the fungal burden of larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone or C. albicans plus ACh showed no significant differences (Fig. 2B). However, 24 h postinoculation, the fungal burden of larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh was significantly reduced 15.6-fold (P < 0.05) compared to that in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone (Fig. 2B).

These data suggest that the inoculation with ACh significantly reduces the fungal biomass in vivo, which in turn prolongs the survival of infected larvae.

Acetylcholine downregulates expression of Candida albicans biofilm-associated genes in vivo.

To test the hypothesis that ACh impacts C. albicans biofilm formation in vivo, we investigated the expression of two genes known to be important in biofilm formation—HWP1 (the hyphal cell wall protein 1 gene) and ALS3 (the agglutinin-like sequence 3 gene) (28).

Four hours postinoculation, the levels of expression of HWP1 and ALS3 were significantly reduced 5.1-fold (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2C) and 1.6-fold (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D), respectively, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh compared to the levels in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone. At 24 h postinoculation, the reduced expression of HWP1 was maintained at 4.9-fold (P < 0.05) in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh (Fig. 2C), and the expression of ALS3 was further reduced to 9.5-fold (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). Therefore, decreased expression of these genes suggests that ACh can inhibit C. albicans hyphal growth and biofilm formation in vivo.

Acetylcholine affects the pathogenesis of Candida albicans infection in vivo.

To visualize the ability of ACh to inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation in vivo and to begin to investigate the role of ACh in the pathogenesis of C. albicans infection, histological analysis was performed.

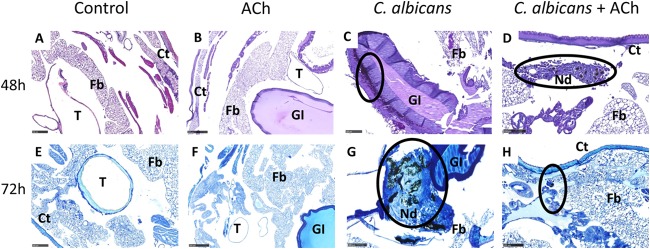

Forty-eight hours postinoculation, both sham PBS inoculation (Fig. 3A) and inoculation with ACh alone (Fig. 3B) had no effects on larval tissues. However, larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone exhibited microvacuolization of the fat body and an increase in hemocytes in larval tissues, such as the fat body and the subcuticular, intestinal, and paratracheal areas, in line with previously reported findings (21). Furthermore, the presence of nodules and multifocal melanization was also observed, as were C. albicans hyphae that exhibited signs of extracellular matrix deposition around intestinal tissues and invasion of the gut walls (Fig. 3C, black circle) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh presented with smaller nodules, which were limited to peripheral larval tissues with no involvement of the gut and tracheal systems. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction in melanization, and no hyphae were present (Fig. 3D, black circle).

FIG 3.

Effects of acetylcholine on Candida albicans biofilm formation and host immunity in vivo. Histological analysis of larvae was performed using periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (A to D) and Giemsa staining (E to H) at 48 and 72 h postinoculation. The control groups are larvae inoculated with PBS (A and E) or ACh (B and F) alone. Black circles highlight Candida albicans biofilm formation in panels C and G and nodule formation, which is representative of hemocyte recruitment and activation, in panels D, G, and H. Representative images are shown from histological analysis of 3 larvae for each condition from 3 independent experiments. Fb, fat body; Ct, cuticle; GI, gastrointestinal tract; T, trachea; Nd, nodule. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Seventy-two hours postinoculation, both sham PBS inoculation (Fig. 3E) and inoculation with ACh alone (Fig. 3F) had no effects on larval tissues. However, larvae infected with C. albicans alone revealed extensive invasion of the intestinal walls and lumen, as well as the tracheal systems. Large nodules were also present at sites of infection and in the fat body (Fig. 3G, black circle). In contrast, larvae infected with C. albicans plus ACh exhibited decreased inflammation and less aggressive fungal infiltration of vital larval tissues, with only small melanized nodules present in the subcuticular areas. In addition, C. albicans hypha formation was not observed, and microvacuolization of the fat body was less appreciable, with a return to nearly normal conditions suggestive of resolution (Fig. 3H, black circle).

The histological evidence adds weight to the hypothesis that ACh can inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation in vivo. In addition, the data also suggest that ACh can also modulate host cellular immune responses against C. albicans.

Acetylcholine modulates Galleria mellonella hemocyte responses to Candida albicans infection.

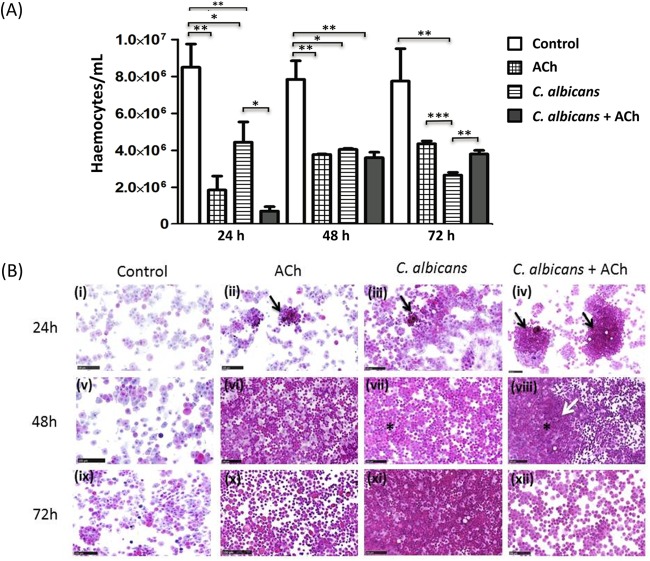

To investigate further the effect of ACh on host cellular immune responses during C. albicans infection hemocyte counts, cytospin analysis and examination of larval histology were performed.

Hemocyte counts revealed that larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone exhibited a significant 2-fold reduction in the number of circulating hemocytes compared to control larvae 24 h postinoculation (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). However, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh, circulating hemocyte numbers were reduced 17-fold (P < 0.01) compared to those in control larvae and reduced 8-fold (P < 0.05) compared to the level in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone. Furthermore, inoculation with ACh alone induced a 4-fold reduction (P < 0.01) in circulating hemocytes compared to control larvae (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Effects of acetylcholine on Candida albicans-induced hemocyte recruitment and activation. (A) Effect of ACh on hemolymph hemocyte counts. Data are expressed as cells per milliliter of hemolymph. The bars represent the mean and standard deviations for at least 3 larvae from 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B) Effect of ACh on C. albicans-induced hemocyte activation as determined by cytospin analysis. Representative images are shown from cytospin analysis of 3 larvae for each condition from 3 independent experiments. Cytosopin analysis for each condition was performed 24 h (i to iv), 48 h (v to viii), and 72 h (ix to xii) postinoculation. Black arrows highlight small aggregates with melanin deposition. A white arrow highlights pronounced aggregation, melanization, and merger of hemocytes into nodules with tissue-like structures. Asterisks highlight homogenous distribution of polymorphic hemocytes immersed in an eosinophilic extracellular matrix. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Forty-eight hours postinoculation, the significant 2-fold decrease in circulating hemocyte numbers observed at 24 h persisted in C. albicans-inoculated larvae compared to control larvae (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). However, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh, hemocyte numbers increased from those observed at 24 h, and as such, there was now only a 2-fold reduction (P < 0.01) in comparison to control larvae. A similar finding was observed in larvae inoculated with ACh alone compared to control larvae (2-fold reduction [P < 0.01]) (Fig. 4A).

Seventy-two hours postinoculation, in larvae inoculated with ACh alone or C. albicans plus ACh, the number of circulating hemocytes continued to rise, and as such, there were no significant differences between either condition and control larvae. In contrast, larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone showed a 3.5-fold decrease in circulating hemocytes compared to control larvae (P < 0.01).

Furthermore, larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone also exhibited a significant 1.4-fold decrease in circulating hemocytes compared to larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh (P < 0.01) and a 1.5-fold decrease compared to larvae inoculated with ACh alone (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A).

Cytospin analysis revealed that 24 h postinoculation, hemocytes from C. albicans-infected larvae (Fig. 4Biii, black arrow) showed small aggregates with melanin deposition (black arrow) compared to controls (Fig. 4Bi). A similar degree of aggregation was observed by hemocytes from larvae inoculated with ACh alone (Fig. 4Bii, black arrow). However, aggregation was more pronounced in hemocytes isolated from larvae infected with C. albicans plus ACh (Fig. 4Biv, black arrows).

Forty-eight hours postinoculation, hemocytes from larvae inoculated with ACh alone (Fig. 4Bvi) or C. albicans plus ACh (Fig. 4Bviii) showed aggregation in a monolayer with less appreciable nodules. Moreover, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh, hemocytes showed pronounced aggregation, and hemocytes merged into nodules with tissue-like structures (Fig. 4Bviii, white arrow) in comparison to larvae infected with C. albicans alone (Fig. 4Bvii). In addition, hemocytes from larvae inoculated with ACh alone (Fig. 4Bvi) or C. albicans plus ACh (Fig. 4Bviii) showed a homogenous distribution of polymorphic hemocytes immersed in an eosinophilic extracellular matrix (asterisk).

Seventy-two hours postinfection, hemocytes from larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone (Fig. 4Bxi) demonstrated complete aggregation in a sole dense tissue-like sheet. In contrast, hemocytes from larvae inoculated with ACh alone (Fig. 4Bx) or C. albicans plus ACh (Fig. 4Bxii) were starting to disaggregate into single hemocytes.

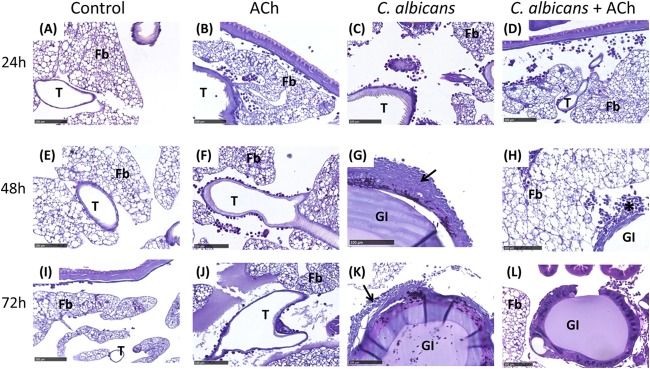

Histological analysis of hemocyte recruitment in vivo (Fig. 5) revealed that in larvae inoculated with ACh alone, only a few hemocytes are recruited around the tracheal tree at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 5B and F), with normal larval histology appreciable at 72 h (Fig. 5J). In larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone, progressive hyphal invasion can be easily observed around the trachea and gut, with progressively extensive hemocyte recruitment 24 to 72 h postinoculation (Fig. 5C, G, and K, black arrows). In contrast, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh, hemocyte aggregation into nodules (Fig. 5H, black asterisk) is observed 24 to 48 h postinoculation, and no hyphal invasion of vital tissues is appreciable (Fig. 5D and H). Furthermore, 72 h postinoculation, nodules have disaggregated, and tissue homeostasis occurs with no appreciable signs of infection (Fig. 5L).

FIG 5.

Effects of acetylcholine on Candida albicans-induced hemocyte recruitment into Galleria mellonella tissues. Histological analysis of hemocyte recruitment into larval tissues was performed using PAS staining 24, 48, and 72 h postinoculation. The control groups are larvae inoculated with PBS (A, E, and I) or ACh (B, F, and J) alone. Larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone (C, G, and K) and C. albicans plus ACh (D, H, and L) are also represented. Extensive hemocyte recruitment is highlighted with black arrows. Hemocyte nodule formation is highlighted with a black asterisk. Representative images are shown from histological analysis of >3 larvae for each condition from 3 independent experiments. Fb, fat body; GI, gastrointestinal tract; T, trachea. Scale bars, 100 μm.

In combination, the hemocyte counts, cytospin analysis, and histology suggest that ACh can induce rapid activation of hemocytes. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that ACh can promote rapid clearance of C. albicans in vivo. Therefore, ACh may be an important regulator of cellular immunity, and this may be another mechanism by which ACh protects larvae against C. albicans-induced mortality.

Acetylcholine induces transient downregulation in Candida albicans-induced expression of host antifungal peptides in vivo.

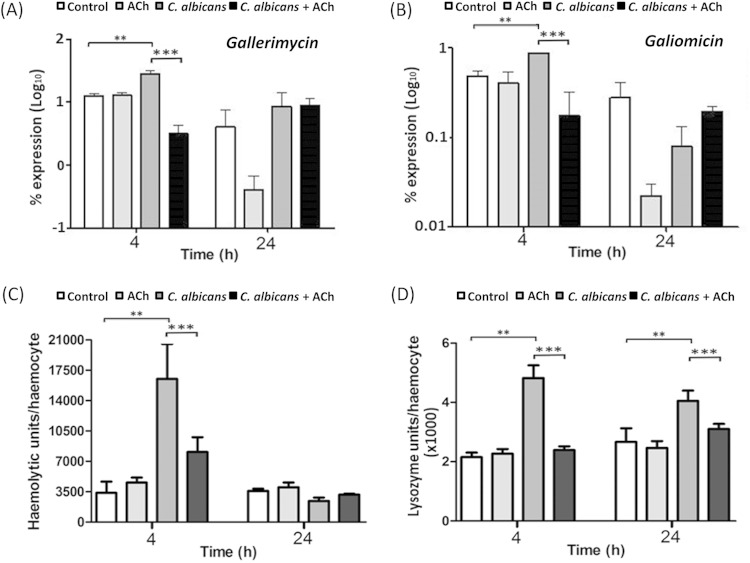

In mammalian systems, ACh has been shown to inhibit the humoral arm of the innate immune response (5, 7). To determine the effect of ACh on humoral components of insect innate immunity, we first used qPCR analysis to investigate expression of antifungal peptides in vivo.

Four hours postinoculation, in comparison to PBS-inoculated controls, expression of gallerimycin and galiomicin was significantly upregulated 2-fold and 4-fold, respectively, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone (both P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A and B). However, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh, expression of gallerimycin and galiomicin was significantly downregulated 9-fold and 5-fold, respectively, compared to expression in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone (both P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A and B). Twenty-four hours postinoculation, no significant differences in gallerimycin or galiomicin expression were found between larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone and those inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh (Fig. 6A and B). Interestingly, in larvae inoculated with ACh alone, expression of both gallerimycin and galiomicin was decreased in comparison to that in control larvae (Fig. 6A and B) at 24 h; however, this was not found to be statistically significant. Altogether, the data suggest that ACh can transiently inhibit the expression of antifungal peptides.

FIG 6.

Effects of acetylcholine on Galleria mellonella antifungal defenses in vivo. Shown are the effects of ACh on expression of gallerimycin (A) and galiomicin (B) mRNA. The percentage of expression was determined and compared to that of a housekeeping gene (ACT1) by the 2−ΔCT method. Each bar shows the mean and standard deviation from three independent experiments performed on 3 larvae in each group (n = 9). (C) Effects of ACh on hemolymph gallysin activity. Gallysin activity was adjusted for hemocyte number. Each bar shows the mean and standard deviation of corrected hemolytic units of activity from 1 μl of hemolymph from 3 larvae in each group in three independent experiments (n = 9). (D) Effects of ACh on hemolymph lysozyme activity. The activity is adjusted for hemocyte number. Each bar shows the mean and standard deviation of corrected units of activity from 1 μl of hemolymph from three independent experiments performed on 3 G. mellonella larvae in each group (n = 9). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

Acetylcholine induces a transient downregulation in Candida albicans-induced hemolymph gallysin activity.

At present, there are no functional assays for gallerimycin and galiomicin activity. However, a functional hemolytic assay for the antifungal peptide gallysin has been reported (27). Therefore, we assessed gallysin activity to determine whether the transient inhibition of antifungal peptide expression was reflected at the protein level.

At 4 h postinoculation, the hemolymph of G. mellonella infected with C. albicans alone had 4.8-fold greater gallysin activity than control larvae (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6C). In contrast, larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh showed no significant increase in gallysin activity. Furthermore, in comparison to larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone, larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh showed a significant 2.1-fold reduction in gallysin activity (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6C). Twenty-four hours postinoculation, no significant differences in gallysin activity were observed (Fig. 6C). Therefore, in agreement with the expression data for gallerimycin and galiomicin (Fig. 6A and B), ACh can transiently inhibit the activity of antifungal peptides.

Acetylcholine downregulates Candida albicans-induced hemolymph lysozyme activity.

In addition to antifungal peptides, we also investigated the effect of ACh on the activity of the antifungal enzyme lysozyme in vivo using an established lysozyme activity assay (26).

The hemolymph lysozyme activity 4 h postinoculation was 2.2-fold greater in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone than in PBS-treated control larvae (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6D). In contrast, larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh showed no significant increase in lysozyme activity. Furthermore, in comparison to larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone, the larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh showed a significant 2.5-fold reduction in lysozyme activity (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6D). Twenty-four hours postinoculation, lysozyme activity was 4.9-fold greater in larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone than in the PBS-treated control larvae (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6D). However, in comparison to larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone, the larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh showed a significant 1.5-fold reduction in lysozyme activity (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6D). Therefore, ACh has an inhibitory effect on the activity of the antifungal enzyme lysozyme.

DISCUSSION

Candidiasis has become increasingly recognized as having a biofilm etiology (21, 29). Recent studies have shown that there is a positive correlation between biofilm-forming ability and poor clinical outcomes (30), which is inextricably linked to C. albicans filamentation (31). In addition, severe C. albicans infection in humans is associated with sepsis, which causes severe complications and potentially death (32). Therefore, small molecules that can inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation, promote rapid cellular immune responses against C. albicans, and at the same time protect against sepsis are attractive therapeutic options.

This study is the first to report a role for ACh in the pathogenesis of C. albicans infection. ACh was found to inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro analysis showed that ACh could dose-dependently inhibit biofilm formation, and the observed effects were not due to cytotoxicity. In vivo analysis revealed larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone exhibited fungal biofilms in tissues with widespread visceral invasion by fungal filaments and the formation of large melanized nodules. In addition, fungal biofilms were commonly observed in vital organs (gastrointestinal tract and trachea); in line with previous findings by Borghi et al. (33). In contrast, in larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh, only yeast cells or stubby hyphae were observed. Furthermore, this was associated with a decrease in fungal burden and decreased expression of key genes that are important in biofilm formation, such as HWP1 and ALS3.

In addition to inhibition of C. albicans biofilm formation, in vivo histological analysis, along with hemocyte counts and cytospin analysis, demonstrated a role for ACh in promoting a rapid cellular immune response to C. albicans infection. Hemocytes from larvae inoculated with ACh alone had enhanced adhesion capabilities, which are associated with activation. However, histological analysis did not reveal increased numbers of hemocytes in tissues of larvae inoculated with ACh alone. Therefore, this piece of data suggested that although ACh can promote hemocyte activation, the presence of C. albicans in tissues is important for the recruitment of the activated hemocytes to the site of infection. Furthermore, evidence for a role of ACh in promoting hemocyte function is provided by the fact that hemocytes from larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh formed melanized nodules and cell monolayers rapidly (both ex vivo and in vivo) and exhibited enhanced entrapment of C. albicans cells both intracellularly and extracellularly. Therefore, ACh can promote rapid and effective immune responses to C. albicans infection in vivo. Interestingly, however, at 72 h postinoculation, larvae inoculated with C. albicans plus ACh revealed a lack of confluent melanized nodules accompanied by disaggregation and progressive hemocyte dispersion and tissue homeostasis. This was reflected by an increase in the number of circulating hemocytes. In contrast, hemocytes of larvae inoculated with C. albicans alone failed to disaggregate and maintained a dense tissue-like pattern even at 72 h postinoculation. Therefore, this piece of data suggests that ACh promotes a rapid and effective cellular immune response to clear C. albicans and possibly prevent inflammation-induced damage of host tissues.

Mouse models have suggested that ACh has anti-inflammatory properties, can inhibit the expression of proinflammatory mediators, and can protect against bacterial sepsis (5, 10, 11). G. mellonella has a range of antifungal defense mechanisms that can protect against C. albicans infection. These include small cationic and hydrophilic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and proteolytic enzymes. Gallerimycin, galiomicin, gallysin, and lysozyme all have antifungal activity (34, 35). In this study, ACh was found to have a transient inhibitory effect on the expression of gallerimycin and galiomicin and the activity of gallysin. Furthermore, a longer-term inhibitory effect of ACh on lysozyme activity was also observed. This piece of data suggested that in line with mammalian models, ACh can inhibit humoral aspects of innate immunity. The biological significance of these findings remains to be elucidated. However, it is interesting to speculate that this transient inhibition of humoral innate immunity occurs in order to allow cellular immune responses to clear the infection before the release of an arsenal of antifungals that may have potential tissue-damaging bystander effects. Indeed, if this hypothesis is correct, it may also explain the rapid resolution of inflammation and tissue homeostasis observed 72 h postinfection. However, further research is required to confirm this hypothesis.

A limitation of this study was that a primitive Galleria mellonella infection model was employed instead of mouse models. However, despite invertebrates being separated by millions of years of evolution from mammals, many aspects of the innate immune system are conserved between the species (36). Therefore, invertebrate models have previously been reported as useful tools for investigating the early inflammatory events that occur during infection. Indeed, the Galleria mellonella model has been successfully reported to model C. albicans virulence, with results found to be comparable to those of mouse infection models (37).

Another limitation of this study is the fact that at present the immune cell subtypes that make up the hemocyte population in Galleria mellonella are still not fully characterized (38). Cytospin analysis suggested that the predominant immune cells were plasmatocytes and granulocytes—cells found to have similar characteristics to human neutrophils (38). Neutrophils are host granulocytes that protect against microbial infections (39) and control fungal pathogens by phagocytizing yeast cells and forming neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in response to hyphae to aid killing and clearance (40). Interestingly, cytospin analysis suggested that hemocytes organize into NET-like structures and that this process was promoted by ACh. NET formation has been reported for hemocytes from G. mellonella and has been suggested to have similarities in appearance and function to vertebrate NETs (41). The effect of ACh on NET formation in both invertebrates and higher mammals is currently unknown. However, from the data described in this article, it is interesting to speculate that ACh may promote hemocyte activation and NET formation to aid clearance of C. albicans. In humans, neutrophils express nAChRs (including α7nAChR), and in vitro activation of nAChRs has been found to promote neutrophil activity by inducing the release of IL-8 (42), elastase, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (43). Furthermore, activation of nAChRs has been shown to inhibit neutrophil apoptosis and promote neutrophil survival as well as maturation (44). Therefore, there is tentative evidence in higher mammals that ACh may indeed promote neutrophil function. However, further comprehensive studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

In conclusion, the data in this article assign two independent roles for ACh in C. albicans pathogenesis: (i) as an inhibitor of C. albicans biofilm formation and pathogenicity and (ii) as a regulator of host cellular immune responses to facilitate rapid clearance of C. albicans. The novel findings described in this article therefore suggest that ACh may be a direct or adjunctive therapeutic to prevent or treat potentially fatal fungal infections.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00067-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mensa J, Pitart C, Marco F. 2008. Treatment of critically ill patients with candidemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 32(Suppl 2):S93–S97. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(08)70007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. 2013. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence 4:119–128. doi: 10.4161/viru.22913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacCallum DM. 2013. Mouse model of invasive fungal infection. Methods Mol Biol 1031:145–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-481-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ. 2000. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature 405:458–462. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, Mak TW, Tracey KJ. 2011. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 334:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jonge WJ, van der Zanden EP, The FO, Bijlsma MF, van Westerloo DJ, Bennink RJ, Berthoud HR, Uematsu S, Akira S, van den Wijngaard RM, Boeckxstaens GE. 2005. Stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates macrophage activation by activating the Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 6:844–851. doi: 10.1038/ni1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macpherson A, Zoheir N, Awang RA, Culshaw S, Ramage G, Lappin DF, Nile CJ. 2014. The alpha 7 nicotinic receptor agonist PHA-543613 hydrochloride inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced expression of interleukin-8 by oral keratinocytes. Inflamm Res 63:557–568. doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0725-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH, Yang H, Ulloa L, Al-Abed Y, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. 2003. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature 421:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su X, Matthay MA, Malik AB. 2010. Requisite role of the cholinergic alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor pathway in suppressing Gram-negative sepsis-induced acute lung inflammatory injury. J Immunol 184:401–410. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huston JM, Ochani M, Rosas-Ballina M, Liao H, Ochani K, Pavlov VA, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ashok M, Czura CJ, Foxwell B, Tracey KJ, Ulloa L. 2006. Splenectomy inactivates the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway during lethal endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis. J Exp Med 203:1623–1628. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giebelen IA, Le Moine A, van den Pangaart PS, Sadis C, Goldman M, Florquin S, van der Poll T. 2008. Deficiency of alpha7 cholinergic receptors facilitates bacterial clearance in Escherichia coli peritonitis. J Infect Dis 198:750–757. doi: 10.1086/590432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giebelen IA, Leendertse M, Florquin S, van der Poll T. 2009. Stimulation of acetylcholine receptors impairs host defence during pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur Respir J 33:375–381. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00103408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lafargue M, Xu L, Carles M, Serve E, Anjum N, Iles KE, Xiong X, Giffard R, Pittet JF. 2012. Stroke-induced activation of the alpha7 nicotinic receptor increases Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung injury. FASEB J 26:2919–2929. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-197384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horiuchi Y, Kimura R, Kato N, Fujii T, Seki M, Endo T, Kato T, Kawashima K. 2003. Evolutional study on acetylcholine expression. Life Sci 72:1745–1756. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawashima K, Fujii T. 2008. Basic and clinical aspects of non-neuronal acetylcholine: overview of non-neuronal cholinergic systems and their biological significance. J Pharmacol Sci 106:167–173. doi: 10.1254/jphs.FM0070073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wessler I, Kilbinger H, Bittinger F, Unger R, Kirkpatrick CJ. 2003. The non-neuronal cholinergic system in humans: expression, function and pathophysiology. Life Sci 72:2055–2061. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajendran R, Sherry L, Lappin DF, Nile CJ, Smith K, Williams C, Munro CA, Ramage G. 2014. Extracellular DNA release confers heterogeneity in Candida albicans biofilm formation. BMC Microbiol 14:303. doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0303-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greetham D, Wimalasena T, Kerruish DW, Brindley S, Ibbett RN, Linforth RL, Tucker G, Phister TG, Smart KA. 2014. Development of a phenotypic assay for characterisation of ethanologenic yeast strain sensitivity to inhibitors released from lignocellulosic feedstocks. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 41:931–945. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cirasola D, Sciota R, Vizzini L, Ricucci V, Morace G, Borghi E. 2013. Experimental biofilm-related Candida infections. Future Microbiol 8:799–805. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherry L, Rajendran R, Lappin DF, Borghi E, Perdoni F, Falleni M, Tosi D, Smith K, Williams C, Jones B, Nile CJ, Ramage G. 2014. Biofilms formed by Candida albicans bloodstream isolates display phenotypic and transcriptional heterogeneity that are associated with resistance and pathogenicity. BMC Microbiol 14:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCulloch E, Ramage G, Rajendran R, Lappin DF, Jones B, Warn P, Shrief R, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Williams C. 2012. Antifungal treatment affects the laboratory diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Pathol 65:83–86. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2011.090464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mylonakis E, Moreno R, El Khoury JB, Idnurm A, Heitman J, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM, Diener A. 2005. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Infect Immun 73:3842–3850. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3842-3850.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perdoni F, Falleni M, Tosi D, Cirasola D, Romagnoli S, Braidotti P, Clementi E, Bulfamante G, Borghi E. 2014. A histological procedure to study fungal infection in the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Eur J Histochem 58:2428. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2014.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shugar D. 1952. The measurement of lysozyme activity and the ultra-violet inactivation of lysozyme. Biochim Biophys Acta 8:302–309. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(52)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beresford PJ, Basinski-Gray JM, Chiu JK, Chadwick JS, Aston WP. 1997. Characterization of hemolytic and cytotoxic gallysins: a relationship with arylphorins. Dev Comp Immunol 21:253–266. doi: 10.1016/S0145-305X(97)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldman M, Al-Quntar A, Polacheck I, Friedman M, Steinberg D. 2014. Therapeutic potential of thiazolidinedione-8 as an antibiofilm agent against Candida albicans. PLoS One 9:e93225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramage G, Robertson SN, Williams C. 2014. Strength in numbers: antifungal strategies against fungal biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 43:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumbarello M, Fiori B, Trecarichi EM, Posteraro P, Losito AR, De Luca A, Sanguinetti M, Fadda G, Cauda R, Posteraro B. 2012. Risk factors and outcomes of candidemia caused by biofilm-forming isolates in a tertiary care hospital. PLoS One 7:e33705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramage G, VandeWalle K, Lopez-Ribot JL, Wickes BL. 2002. The filamentation pathway controlled by the Efg1 regulator protein is required for normal biofilm formation and development in Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 214:95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaloye J, Calandra T. 2014. Invasive candidiasis as a cause of sepsis in the critically ill patient. Virulence 5:161–169. doi: 10.4161/viru.26187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borghi E, Romagnoli S, Fuchs BB, Cirasola D, Perdoni F, Tosi D, Braidotti P, Bulfamante G, Morace G, Mylonakis E. 2014. Correlation between Candida albicans biofilm formation and invasion of the invertebrate host Galleria mellonella. Future Microbiol 9:163–173. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown SE, Howard A, Kasprzak AB, Gordon KH, East PD. 2009. A peptidomics study reveals the impressive antimicrobial peptide arsenal of the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 39:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sowa-Jasilek A, Zdybicka-Barabas A, Staczek S, Wydrych J, Mak P, Jakubowicz T, Cytrynska M. 2014. Studies on the role of insect hemolymph polypeptides: Galleria mellonella anionic peptide 2 and lysozyme. Peptides 53:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann JA, Kafatos FC, Janeway CA, Ezekowitz RA. 1999. Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science 284:1313–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maccallum DM. 2012. Hosting infection: experimental models to assay Candida virulence. Int J Microbiol 2012:363764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browne N, Heelan M, Kavanagh K. 2013. An analysis of the structural and functional similarities of insect hemocytes and mammalian phagocytes. Virulence 4:597–603. doi: 10.4161/viru.25906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson M, Rautemaa R. 2009. How the host fights against Candida infections. Front Biosci 14:246–257. doi: 10.2741/s24,. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Branzk N, Lubojemska A, Hardison SE, Wang Q, Gutierrez MG, Brown GD, Papayannopoulos V. 2014. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat Immunol 15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altincicek B, Stotzel S, Wygrecka M, Preissner KT, Vilcinskas A. 2008. Host-derived extracellular nucleic acids enhance innate immune responses, induce coagulation, and prolong survival upon infection in insects. J Immunol 181:2705–2712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iho S, Tanaka Y, Takauji R, Kobayashi C, Muramatsu I, Iwasaki H, Nakamura K, Sasaki Y, Nakao K, Takahashi T. 2003. Nicotine induces human neutrophils to produce IL-8 through the generation of peroxynitrite and subsequent activation of NF-kappaB. J Leukoc Biol 74:942–951. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saareks V, Mucha I, Sievi E, Vapaatalo H, Riutta A. 1998. Nicotine stereoisomers and cotinine stimulate prostaglandin E2 but inhibit thromboxane B2 and leukotriene E4 synthesis in whole blood. Eur J Pharmacol 353:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu M, Scott JE, Liu KZ, Bishop HR, Renaud DE, Palmer RM, Soussi-Gounni A, Scott DA. 2008. The influence of nicotine on granulocytic differentiation—inhibition of the oxidative burst and bacterial killing and increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 release. BMC Cell Biol 9:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergin D, Murphy L, Keenan J, Clynes M, Kavanagh K. 2006. Pre-exposure to yeast protects larvae of Galleria mellonella from a subsequent lethal infection by Candida albicans and is mediated by the increased expression of antimicrobial peptides. 8:2105–2112. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.