Abstract

Background

The blotchy mouse caused by mutations of ATP7A develops low blood copper and aortic aneurysm and rupture. Although the aortic pathologies are believed primarily due to congenital copper deficiencies in connective tissue, perinatal copper supplementation does not produce significant therapeutic effects, hinting additional mechanisms in the symptom development, such as an independent effect of the ATP7A mutations during adulthood.

Methods

We investigated if bone marrow from blotchy mice contributes to these symptoms. For these experiments, bone marrow from blotchy mice (blotchy marrow group) and healthy littermate controls (control marrow group) was used to reconstitute recipient mice (irradiated male low-density lipoprotein receptor −/− mice), which were then infused with angiotensin II (1,000 ng/kg/min) for 4 weeks.

Results

By using Manne–Whitney Utest, our results showed that there was no significant difference in the copper concentrations in plasma and hematopoietic cells between these 2 groups. And plasma level of triglycerides was significantly reduced in blotchy marrow group compared with that in control marrow group (P<0.05), whereas there were no significant differences in cholesterol and phospholipids between these 2 groups. Furthermore, a bead-based multiplex immunoassay showed that macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A production was significantly reduced in the plasma of blotchy marrow group compared with that in control marrow group (P<0.05). More important, although angiotensin II infusion increased maximal external aortic diameters in thoracic and abdominal segments, there was no significant difference in the aortic diameters between these 2 groups. Furthermore, aortic ruptures, including transmural breaks of the elastic laminae in the abdominal segment and lethal rupture in the thoracic segment, were observed in blotchy marrow group but not in control marrow group; however, there was no significant difference in the incidence of aortic ruptures between these 2 groups (P = 0.10; Fisher's exact test).

Conclusions

Overall, our study indicated that the effect of bone marrow from blotchy mice during adulthood is dispensable in the regulation of blood copper, plasma cholesterol and phospholipids levels, and aortic pathologies, but contributes to a reduction of MIP-1β, MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, TIMP-1, and VEGF-A production and triglycerides concentration in plasma. Our study also hints that bone marrow transplantation cannot serve as an independent treatment option.

INTRODUCTION

The blotchy mouse is an animal model mimicking the connective tissue defects and, to a lesser extent, the neurodegeneration in human Menkes disease, which is an X-linked genetic disorder caused by mutations affecting ATP7A function. Affected male subjects usually die before 2–3 years of age. Affected females are generally heterozygous carriers, who appear healthy, presumably because the relative surfeit of the wild-type protein overcomes the negative influence of the mutant protein. Thus, in this article, the discussed Menkes disease patients and blotchy mice refer to the affected male subjects. ATP7A, also known as Menkes disease protein or copper-transporting P-type ATPase, regulates the copper transport at 2 different levels. At a cellular level, this transporter regulates copper egress, as indicated by an increase of copper levels in cultured fibroblasts,1 lymphoblasts,2 muscle cells,3 and macrophages (MΦs)4,5 isolated from Menkes disease patients and mouse models. At the organ level, ATP7A primarily controls dietary copper absorption in the intestine, as indicated by the increased copper levels in intestine and decreased copper levels in most other tissues.6–8 These observations hint that the uptake of copper by the intestine appears normal but the delivery of copper to the blood is impaired. Consequently, most organs exhibit reduced activity of copper-dependent enzymes, such as dopamine-β-hydroxylase,9,10 cytochrome oxidase,9,11 lysyl oxidase,12,13 and extracellular superoxide dismutase.14–16 Furthermore, recent studies demonstrated that ATP7A functions a variety of signaling pathways, including neuron-regulated glutamatergic signaling,17 MΦ-elicited bactericidal activity18 and oxidation of low-density lipoprotein,19 smooth muscle cell migration,20 and cancer multidrug resistance.21,22 Thus, ATP7A is evolving from a copper transporter to a multifunctional protein.

Vascular defects in patients with Menkes disease were first discovered by observing the marked tortuosity of the cerebral arterial systems.23 In addition to tortuosity, vascular dilation and aneurysm were also observed in systemic arteries, such as the carotid, pulmonary, lumbar, iliac, splenic, and hepatic arteries,24–30 in smaller arteries, such as brachial artery,31 and in veins, such as cerebral venous sinuses.32 The major pathohistologic feature of the vascular defects includes thinning, fragmentation, and/or extensive depletion of elastic laminae in the media.24,33–35 Surgery and endovascular stents can prevent ruptures. However, failed or no treatment results in a fatal rupture.36,37 Interestingly, tortuosity and aneurysm were not reported in aorta. For example, a normal abdominal aorta, but marked tortuous visceral and renal vessels were reported in a 5–6-month-old patient,25 hinting that the defects in the abdominal aorta were grossly unremarkable during the perinatal period. However, histologic sequestration and degradation of aortic elastin have been reported. For instance, in the thoracic aorta of an 18-month-old patient, there was a partial depletion of elastic laminae in the inner media and fragmentation of the elastic laminae in the middle and the outer media.38 This was accompanied by marked collagen accumulation, hinting a generalized repair response.38 Thus, it is reasonable to predict that these histologic changes in the elastic laminae would result in aortic dilation (aneurysm) and likely rupture if these patients lived for a longer period, similar to Marfan syndrome patients. Moreover, aortic elastin sequestration in Menkes disease patients indicates that ATP7A is a candidate protein related to the risk of aortic aneurysm and rupture in humans.

There are 2 major characteristics of aortic pathologies in blotchy mice, including early aortic rupture and late aortic aneurysm.39 Interestingly, the areas of aortic rupture do not always correspond to its severity.39 Most aneurysms occur in the ascending segment but are also observed in the descending and abdominal segments.40 The dominant theory to interpret the cause of the disease is because of the effect of congenital copper deficiency on reduced activity of lysyl oxidase, an enzyme regulating the cross-linking of elastin and collagen in vascular walls. However, copper supplementation cannot produce significant therapeutic benefits, hinting the involvement of other mechanisms beyond the congenital period. For example, we investigated the inflammatory mediator production in peritoneal MΦ isolated from blotchy mice versus controls and found that the production of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) does not differ significantly between these 2 groups, whereas vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) and monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 are significantly downregulated,41 which is consistent with the concept that inherited forms of aortic aneurysm is typically less inflamed.42 These findings hint at a unique inflammatory pattern associated with aortic rupture and aneurysm in blotchy mice, although little is known in which extent these changes contribute to the pathogenesis of aortic pathologies in blotchy mice.

Both resident and migrated cells of the vascular walls contribute to aortic pathologies. It is unknown to what extent ATP7A-expressing cell types are contributing to the aortic pathologies in blotchy mice. Although transplantation of bone marrow into adult mice offers a validated approach to study the role of migrated cells in aortic pathologies, a major challenge of studying adult aortic aneurysm is because its natural course is chronic, gradually abating over the years. Propitiously, the natural course can be markedly accelerated by the administration of certain chemicals, such as the subcutaneous infusion of hypercholesterolemic mice with angiotensin II, which induces aortic aneurysm and rupture in both the abdominal and thoracic segments.43,44 The rationale of this model is primarily derived from the fact that the involvement of angiotensin II pathway in the formation of thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysm has been highlighted in several clinical trials,45 whereas hypercholesterolemia is considered as an independent risk factor for human abdominal aortic aneurysm.46 Furthermore, genetically modified bone marrow targeting certain proteins can significantly modulate angiotensin II-induced aortic pathologies.47,48 Thus, we recently investigated whether bone marrow from blotchy mice controls blood copper levels, inflammatory mediator production, lipid profiles, and aortic pathologies using this widely-accepted mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

ATP7A-deficient heterozygous female mice (B6Ei.Cg-Atp7aMo-blo), green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice (C57BL/6-Tg[CAG-EGFP] 131Osb/LeySopJ), low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) −/− mice (B6.129S7-Ldlrtm1Her), and C57BL/6 male mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Note that blotchy mice (male hemizygotes carrying X-linked ATP7A mutations49) are usually obtained through in-house breeding ATP7A-deficient female heterozygotes and C57BL/6 males. Two mutations identified in ATP7A in blotchy mice are an out-of-frame deletion of a single 92-bp exon that encodes for the region adjacent to the fourth transmembrane domain and a splice-donor mutation (A–C) in the intron adjacent to the 92-bp exon.50 In our study, ATP7A-deficient female heterozygotes were crossed with GFP transgenic males to produce 2 new mouse strains: blotchy; GFP (Fig. 1A) and wild type (WT); GFP mice. The animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of genetically modified mice used in this study. (A). Representative appearance of blotchy; GFP mice. Under a fluorescent light, the blotchy mice (C57BL/6 background) presented a classic gray coat (left). Under an ultraviolet light (365 nm), green fluorescence was detected at the paws and inner surface of the ears of the mouse, which was pointed by the white arrows (right). (B) Genotypes of the genetically modified mice used in this study. Representative results for genotypes of LDLR −/− mice (top), GFP transgenic mice (middle), and recipient mice reconstituted with marrow from blotchy and WT mice (bottom). M represents DNA ladders to estimate the molecular size of each product. A1–G1 represent test numbers of each experiment. (C). Representative flow cytometry plots reflecting the percentage of GFP + cells in peritoneal exudates in mice reconstituted with bone marrow and GFP transgenic mice. After exclusion of debris and cell clusters using scatter gate, GFP gate was used to select GFP + cells. At least 20,000 events were analyzed for each sample.

Genotyping

Genomic DNAs were obtained from mouse tail snips or blood samples. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was employed for the genotyping of LDLR −/− mice and GFP transgenic mice (Fig. 1B). Three primers were used for the genotyping of LDLR −/− mice. The sequence of the common primer is CCA TAT GCA TCC CCA GTC TT, whereas that of the LDLR −/− mouse-specific primer is AAT CCA TCT TGT TCA ATG GCC GAT C, and the WT mouse-specific primer is GCG ATG GAT ACA CTC ACT GC. The amplicon size for knockout mice is 350 bp, and that for WT mice is 167 bp. In addition, 4 primers were used for the genotyping of GFP mice. The primer sequences for the transgenic mice are AAG TTC ATC TGC ACC ACC G (forward) and TCC TTG AAG AAG ATG GTG CG (reverse); their amplicon size is 173 bp. The primer sequences for internal positive control are CTA GGC CAC AGA ATT GAA AGA TCT (forward) and GTA GGT GGA AAT TCT AGC ATC ATC C (reverse); their amplicon size is 324 bp.

PCR followed by restriction enzyme digestion was conducted for the genotyping of blotchy mice and mice reconstituted with blotchy marrow (Fig. 1B). First, 2 primers were used to amplify the target from genomic DNAs isolated from mouse peripheral blood using PCR. The primer sequences are GGG CAA AAC CTC CGA GGC (forward) and CTG ACC TCC ACA CAT GTG TCA T (reverse); their amplicon size is 187 bp. Then, the amplicons were digested with the restriction enzyme, AvaII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The amplicons from blotchy mice are digested to produce 2 fragments with a similar size, whereas the amplicons from WT mice cannot be digested.

Bone Marrow Transplantation

Blotchy; GFP or WT; GFP mice aged 3–4 months (donors) and LDLR −/− mice aged 2–3 months (recipients) were used to create chimeras. One week before radiation, the recipient mice were given acidified (pH 2.6) water containing neomycin (0.2 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and polymyxin B (0.02 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). During radiation, a total of 900 centiGrays (cGy) was administered at a rate of 98.1 cGy/min to eradicate bone marrow stem cells from the recipient mice using a 137Cesium source. Bone marrow was isolated from the donor mice by flushing their femurs with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (GIBCO™, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), followed by disrupting the marrow through a 25-ga needle and filtering through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After centrifugation at ×250 g for 5 min, the pellet was resuspended in Hank's balanced salt solution (Invitrogen). Four hr after radiation, these marrow cells (5 × 106) were injected into the tail veins of recipient mice. The mice were kept on antibiotic water for 4 weeks after radiation before further experiments.

Bone Marrow Transplant Engraftment Analysis

Although the protein level of mutant ATP7A in the tissues of blotchy mice was reduced, substantial expression was readily detected with normal protein size (data not shown). Thus, using ATP7A expression to determine engraftment efficiency is not highly accurate. To overcome this limitation, we introduced GFP into blotchy and WT mice. This strategy enabled us to determine the engraftment efficiency of donor cells by measuring the percentage of GFP + cells in the peritoneal exudates of recipient mice using flow cytometry.

To obtain peritoneal exudates, 1 mL of 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was administered via intraperitoneal injection, and peritoneal exudates were harvested after 60 sec of peritoneal massage. After centrifugation at ×250 g for 5 min, the supernatant of the exudates was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of erythrocyte lysis buffer (Hybri-Max™, Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 1 min to eliminate occasional erythrocyte contamination during exudate collection. Next, the mixtures were washed with RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 mg/L of streptomycin. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 1× PBS for flow cytometry analysis. This approach was applied at the end of the experiments immediately after sacrificing the mice to accurately determine the engraftment efficiency. The median percentage of GFP + cells was 99.1% (98.7–99.4) for GFP transgenic mice (n = 3), 93.9% (92.1–93.9) for the control marrow group (n = 5), and 92.0% (90.8–92.6) for the blotchy marrow group (n = 5; Fig. 1C). There was no significant difference between the 2 groups of recipient mice (P = 0.11). In contrast, in nonGFP mice, the percentage of GFP + cells was less than 0.01%.

Diet and Angiotensin II Infusion

At 4 weeks after bone marrow transplantation, the 2 groups of recipient mice were fed a high-fat diet (TD.88137; Harlan Laboratories, Houston, TX) for 1 week and then coadministered angiotensin II (1,000 ng/kg/min; Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 weeks. Angiotensin II was administered via osmotic minipumps (ALZET™, model 2004; DURECT Corporation, Cupertino, CA) as previously described.15,51,52

Plasma Copper Concentration Measurements

After euthanasia, whole blood was collected through the right ventricle of the heart and transferred to a microtainer™ tube with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (BD Biosciences). Plasma was separated from hematopoietic cells via centrifugation at ×2,000 g at 4° C for 10 min. For copper detection, cells were digested in a hot block apparatus by nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide, and plasma was diluted. Subsequently, the samples were analyzed to determine the copper concentration via inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry.

Plasma Lipid Profile Measurements

Colorimetric assays were used to determine the concentrations of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and phospholipids in plasma. These assays were performed at the Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center of the University of Cincinnati.

Plasma Inflammatory Mediator Profiling

Twenty-seven inflammatory mediators were analyzed in plasma through a bead-based multiplexing immunoassay as previously described.41,53 These mediators included fibroblast growth factor 9, granulocyte-MΦ colony-stimulating factor, growth-regulated α protein (KC/GRO), interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-γ-inducible protein (IP)-10, IL-1α, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-7, IL-11, IL-12p70, IL-17A, lymphotactin, stem cell factor (SCF), MΦ inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β, MIP-2, MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, oncostatin-M, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1, TNF-α, and VEGF-A. This assay was validated by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay54,55 and has been widely used for inflammatory mediator profiling in murine and human samples.56

Vascular Histology

Aortas fixed by 10% neutrally buffered formalin were trimmed with adventitia and other irrelevant tissues and then photographed using a digital camera attached an AmScope 3.5×–45× circuit board boom stereomicroscope, and the maximal external diameters of ascending and suprarenal aortas were measured using the ROI manager tools from NIH ImageJ software (available at rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) that can measure a 2-point distance on a photograph. Briefly, the first step was to determine the ratio between actual length and photograph distance using a scale ruler's photograph that was taken using the same magnification as aorta photographs. The second step was to measure the photograph distance of aortic diameter using aorta photographs. The final step was to calculate the actual length of each aortic diameter using the ruler ratio. Aorta segments with representative lesions were embedded in paraffin for serial sectioning. Serial sections were obtained and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to determine general morphology, Masson trichrome staining for collagen, and Verhoeff van Gieson staining for elastin organization.

Statistics

Quantitative variables, including engraftment efficiency, plasma copper concentrations, lipid profiles, and inflammatory mediator concentrations, were expressed as the median (interquartile range) and were compared in a Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Qualitative variable, including the incidence of aortic rupture, was expressed as the number (percentage) and was compared by the Fisher's exact test. Significant differences were defined as those with P values <0.05 (2-sided). All statistical analysis was performed with Stata software version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

There Was No Significant Difference in the Median Copper Concentrations in Plasma and Hematopoietic Cells

To determine whether the bone marrow of blotchy mice influences the plasma copper concentration, we compared the copper concentrations between these 2 groups of recipient mice. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference in the median plasma copper concentration between blotchy and control marrow groups (624 μg/L [623–657] vs. 653 μg/L [583–662]; P = 0.92; n = 5; Fig. 2, left panel). In the parallel experiment, the median plasma copper concentration in blotchy mice was 367 μg/L (353–381; n = 2), representing an approximately 40% reduction compared with the recipient mice. This result is comparable to a previous study showing a significant 46% reduction of plasma copper in blotchy mice compared with controls.57

Fig. 2.

Median copper concentration in plasma and hematopoietic cells of LDLR −/− or mice reconstituted with control blotchy marrow after angiotensin II infusion. Fifty microliters of plasma was diluted and hematopoietic cells were digested in a hot block apparatus by nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide. The resulting samples were then analyzed to determine copper concentrations via inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Three replicate measurements were performed for each sample, and the final reported concentration was the mean value of these 3 replicates. Circles and triangles represent values from individual mice, diamonds are median values of each group, and bars are interquartile range. n = 5 for each group.

Our results also showed that the copper concentration in the hematopoietic cells of the peripheral blood did not differ significantly between mice reconstituted with blotchy or control marrow (799 ng/g [759–811] vs. 722 ng/g [707–786]; P = 0.47; n = 5; Fig. 2, right panel). In the parallel experiment, the median copper concentration in hematopoietic cells in blotchy mice was 672 ng/g (601–743; n = 2); although copper concentration in these cells in blotchy mice at nearly normal levels was unexpected, a previous study observed the normal levels of copper in red blood cells in the patients with Menkes disease.33 Thus, the cells/plasma ratio of the median copper concentration is likely a better parameter to reflect the integrated copper abnormality in the blood of blotchy mice. The ratio was 1.22 vs. 1.11 between blotchy and control marrow groups, whereas 1.83 for blotchy mice, which indicates that by correction of copper concentration in plasma, a greater relative amount of copper was accumulated in the hematopoietic cells of blotchy mice compared with those of recipient mice.

Median Triglycerides Concentration Was Significantly Reduced in Mice Reconstituted with Blotchy Marrow

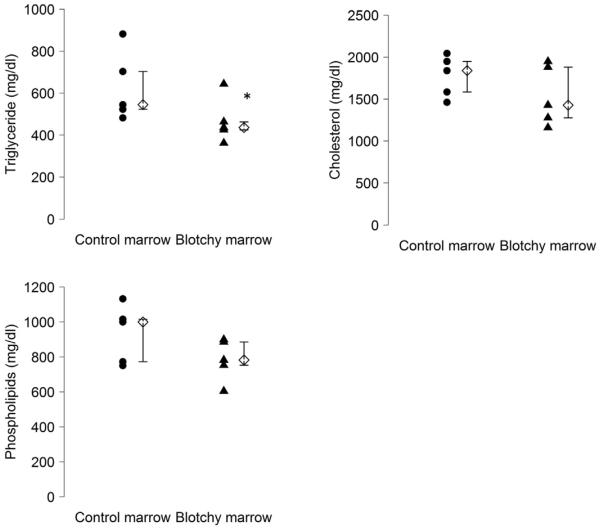

We determined whether the bone marrow of blotchy mice influenced lipid profile in plasma. Our results showed that median triglycerides concentration was significantly reduced in blotchy marrow group, 436 mg/dL (425–463), compared with that in control marrow group, 545 mg/dL (524–704; P = 0.047; n = 5). In contrast, there was no significant change in the concentration of total cholesterol and phospholipids (P = 0.21 and 0.25, respectively, n = 5; Fig. 3). As a control, the median base line concentration of LDLR −/− mice (under regular diets, Harlan 7012; n = 3) was 182 mg/dL (130–204) for triglyceride, 142 mg/dL (118–183) for total cholesterol, and 336 mg/dL (274–402) for phospholipids, which indicates that the mice used for our study were hypercholesterolemic.

Fig. 3.

Median concentrations of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and phospholipids in the plasma of LDLR −/− mice reconstituted with control or blotchy marrow after angiotensin II infusion. Fifteen microliters of plasma was used to determine the concentrations of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and phospholipids through specific colorimetric assays. Circles and triangles represent values from individual mice, diamonds are median values of each group, and bars are interquartile range. *P < 0.05, n = 5 for each group.

Median Inflammatory Mediator Productions Were Reduced in Recipient Mice with Blotchy Marrow

We investigated the inflammatory mediator production in the plasma between the 2 groups of recipient mice. Among the 27 mediators listed in the Materials and Methods section, 12 were readily detected (Fig. 4; n = 5), indicating low-grade inflammation during chronic angiotensin II infusion. The median concentrations of KC/GRO, IP-10, lymphotactin, MIP-2, SCF, and RANTES showed no difference between these 2 groups. The median concentrations of 6 other mediators were significantly reduced in the blotchy marrow group compared with those in the control marrow group: MIP-1β (287 pg/mL [267–348] vs. 450 pg/mL [430–485]; P = 0.028), MCP-1 (67 pg/mL [66–79] vs. 127 pg/mL [111–155]; P = 0.021), MCP-3 (158 pg/mL [148–171] vs. 199 pg/mL [173–244]; P = 0.047), MCP-5 (16 pg/mL [13–19] vs. 21 pg/mL [20–23]; P = 0.028), TIMP-1 (1.4 ng/mL [1.4–1.6] vs. 2.3 ng/mL [2.0–2.3]; P = 0.026), and VEGF-A (526 pg/mL [486–565] vs. 645 pg/mL [645–686]; P = 0.047).

Fig. 4.

Median concentrations of inflammatory mediators in the plasma of LDLR −/− mice reconstituted with control or blotchy marrow after angiotensin II infusion. Twelve inflammatory mediators were detected in plasma using a bead-based multiplexing immunoassay (Myriad RBM, Austin, TX) as previously described.41,53 Circles and triangles represent values from individual mice, diamonds are median values of each group, and bars are interquartile range. *P < 0.05, n = 5 for each group.

Angiotensin II Infusion Increased Median Maximal External Aortic Diameters in Thoracic and Abdominal Segments within These 2 Groups, but There Was No Significant Difference

To investigate the role of bone marrow in the aortic pathologies of blotchy mice, bone marrow from blotchy mice (blotchy marrow) and healthy littermate controls (control marrow) was used to reconstitute recipient mice (irradiated male LDLR −/− mice), which were then infused with angiotensin II (1,000 ng/kg/min) for 4 weeks. Compared with the sham control groups, angiotensin II infusion increased median maximal aortic diameters of abdominal aorta in control marrow group (increased by 42% [41–62]) and blotchy marrow group (increased by 48% [45–102]), but there was no significant difference (P = 0.35; n = 5; Fig. 5). Specifically, the median aortic diameters were 1.05 mm (1.05–1.2) and 1.10 mm (1.07–1.49) for control and blotchy marrow groups, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Median percentage of dilation (A) and rupture (C) of abdominal and ascending aorta in LDLR −/− mice reconstituted with control or blotchy marrow after angiotensin II infusion. The representative photographs of ascending and suprarenal segments of aortas were taken by a camera attached to a stereomicroscope (B). Scale bar: 0.3 cm. Then, maximal external aortic diameters of these segments from mice with angiotensin II (a) and sham controls (b) were measured using NIH ImageJ software (available at rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The formula for calculating the percentage of aortic dilation was (a − b)/b × 100%. Circles and triangles represent values from individual mice, diamonds are median values of each group, and bars are interquartile range. For aortic dilation study, n = 5 for each group. For aortic rupture study, n = 10–12 for each group.

Compared with the sham control group, angiotensin II infusion also increased median maximal aortic diameters of thoracic aorta in control marrow group (increased by 27%[23–40]) or blotchy marrow group (increased by 32% [28–39]), but there was not significant difference between blotchy and control marrow groups (P = 0.84; n = 5; Fig. 5). Specifically, the median aortic diameters were 1.38 mm (1.33–1.51) and 1.42 mm (1.39–1.50) for control and blotchy groups, respectively.

There Was No Significant Difference in Angiotensin II-Induced Aortic Rupture in Mice Reconstituted with Blotchy Marrow versus Those with Control Marrow

In addition to aortic dilation, a classical pathologic feature of angiotensin II-infused model is aortic rupture, such as transmural breaks followed by a prominent thrombus in the region of the suprarenal aorta, although bone marrow radiation in general reduces the incidence of the aortic pathologies likely because of its immunosuppressive effect. Among 12 mice from blotchy marrow group, our results showed that 3 mice (25%) presented this classical pathology accompanied by collagen accumulation after 4 weeks of angiotensin II administration (Figs. 5C and 6A), whereas it was not observed in the control marrow group (0 of total 10 mice). In addition, 1 mouse (8%) in the blotchy marrow group died due to the lethal rupture of the descending aorta (Figs. 5C and 6B). There was no significant difference in the incidence of the aortic rupture (transmural breaks + lethal rupture) between these 2 groups (P = 0.10, Fisher's exact test).

Fig. 6.

Representative pathology of murine aortic rupture in angiotensin II-infused LDLR −/− mice reconstituted with blotchy marrow. (A) Representative transmural elastin breaks and thrombus in the suprarenal aorta of angiotensin II-infused LDLR −/− mice reconstituted with blotchy marrow. Cross-sections were stained with H&E (middle right), Verhoeff van Gieson (left and top right), and Masson trichrome (bottom right). The black arrow points to one end of an elastin break. Scale bar: 1 mm. (B) Thoracic aortic rupture in angiotensin II-infused LDLR −/− mice reconstituted with blotchy marrows. A dead mouse was found during regular inspection. After opening the chest, gross examination showed a bilateral hemothorax. After removing the clotted blood in the chest, a bit of clotted dark blood (white arrow) was well wrapped by a membrane and next to the heart, hinting the rupture (left bottom; scale bar: 1 cm). After isolated the thoracic aorta, clotted dark blood was clearly observed (left top). Cross sections of the lesion were stained by H&E (right; scale bar: 100 μm).

It is interesting to note that the rupture in the suprarenal aorta was restricted by the adventitia (Fig. 6A) so that the mice still survived, whereas rupture in the descending aorta (Fig. 6B) led to immediate death of the mouse. The immediate death after rupture was evidenced by the observation that the prominent thrombus contained smaller numbers of inflammatory cells (Fig. 6B).

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that bone marrow from blotchy mice during adulthood plays a minor role in the regulation of blood copper levels and aortic pathologies in blotchy mice, but contributes to a reduction of MIP-1β, MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, TIMP-1, and VEGF-A production and triglycerides concentration in blood. More important, this study sheds some lights on the regulation of copper and lipid metabolism in blood, pathogenesis of aortic dysfunction in blotchy mice, and the potential vascular function of ATP7A, which will be discussed here.

Our study demonstrated that bone marrow transplantation provides a useful tool to understand copper metabolism in blood. First, because copper concentrations in blood did not significantly differ between the 2 groups of recipient mice, this result supports the concept that decreased copper levels in plasma of Menkes disease patients are primarily because of the reduced dietary copper absorption in the intestine. The second question appears more complicated but intriguing; do hematopoietic cells themselves play a role in regulation of copper level in blood? Assuming that equal amounts of copper are absorbed from the diet, equal amounts of copper would be allocated to the circulatory system. Therefore, we would first expect our bone marrow transplantation model to be comparable to an in vitro cell culture model that involves placing ATP7A-deficient and WT cells into a system (body fluid versus cell culture medium) with the similar copper concentration. In cell cultures, such as in fibroblasts from Menkes disease patients, cellular copper contents are increased whereas extracellular copper concentrations are presumably decreased, reflecting that the ATP7A functions as a copper egress pump at a cellular level. It should be noted that in most cell culture studies, the copper concentrations in conditioned media were not reported. However, our results showed that copper concentrations in the plasma and hematopoietic cells did not significantly differ between the 2 groups of recipient mice, indicating that the bone marrow transplantation model is more complicated than an in vitro cell culture model. For example, a compensatory mechanism might be initiated to provide extra copper, and therefore, to recover the reduced copper level in plasma in the blotchy marrow group. There are several sources that can potentially provide such extra copper. The first candidates are the endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells of the blood vessels. The second is the elastic laminae, which a recent study indicated to serve as a major copper reservoir in blood vessels.58,59 Thus, our current result does not exclude the possible minor role of blood cells in copper regulation in blood.

Our study also provides a unique opportunity to understand the vascular function of ATP7A. We detected reduced production of 6 inflammatory mediators, which can be divided into 3 functional groups: cell migration (MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, and MIP-1β), regulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity (TIMP-1), and angiogenesis (VEGF-A). And these functions are closely associated with the vascular remodeling and/or aortic pathologies. For example, overexpression of TIMP-1 locally60 or in apolipoprotein E −/− mice61 reduces MMP activity and prevents aortic aneurysm, whereas aortic rupture is significantly increased under a combined deficiency of TIMP-1 and apolipo-protein E.62 Furthermore, MCPs belong to a group of potent chemoattractants for monocytes and MΦ.63 MCPs and MIPs appear to belong to the same signaling pathway involved in the regulation of the cell migration.64 In the present study, we found that the levels of MCP-1, MCP-5, and MIP-1β in plasma were reduced in the blotchy marrow group. In a previous study using THP-1 cells as a MΦ model cell,65 ATP7A downregulation in THP-1 cells is associated with reduced cell accumulation in dermal wounds.5 In addition, ATP7A downregulation inhibits the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells in response to platelet-derived growth factor and wound scratch.20 Thus, it is highly likely that ATP7A downregulation inhibits the migration of hematopoietic cells via decreasing the expression of MCPs. In a study using a murine carotid aneurysm model, MCP-1 administration was found to promote inflammatory vascular repair,64 highlighting the protective role of MCP-1 during vascular remodeling and repair. Finally, because angiogenesis is sensitive to copper,66,67 ATP7A is expected to regulate angiogenesis via modulating copper metabolism. Thus, it is surprising to observe the reduced VEGF-A production in blotchy marrow group without a significant change in plasma copper. However, this result hints that ATP7A might regulate angiogenesis via both copper-dependent and independent pathways. Note that the effect of copper-independent pathway appears minimal, because statistic difference is merely within borderline (P = 0.047). Overall, reduced production of MCPs, TIMP-1, and VEGF-A provides mechanistic insights to understand the potential role of ATP7A in vascular remodeling.

Consistent with the observation of reducing lipid accumulated in the aortic wall of blotchy mice39 and decreasing MΦ-induced oxidation of low-density lipoprotein in ATP7A-downregulated cells,19 we found reduced triglycerides concentration in blotchy marrow group. Plasma triglycerides are carried in apolipoprotein B-lipoproteins.68 So far, little is known about the independent role of triglycerides in the development of aortic aneurysm. Previous studies in vitro showed that triglycerides can form a complex with elastin, which might prevent elastolysis.69

It is also important to recognize that inflammatory cell accumulation in aortic aneurysm is regulated by a complicated system. For example, in Figure 6A, our H&E staining showed that a marked amount of inflammatory cell was accumulated in the intraluminal thrombus after transmural breaks. Thus, it is likely that the secondary promoting effect of thrombus on inflammatory cell infiltration prevails over the primary inhibitory effect of ATP7A deficiency under these circumstances.

Finally, reduction of TIMP-1 and MCP-1 in blotchy marrow group does not produce significant aortic dilation and rupture in our model, hinting that relative small changes in these inflammatory mediators such as we observed might not affect aortic aneurysm formation induced by angiotensin II significantly. Thus, bone marrow transplantation might not serve as an independent treatment option. The future study should more focus on the combined effect of bone marrow transplantation with other treatment by correcting the effect of copper deficiency.

[General translational research implication] Aortic aneurysm and rupture accommodates both genetic and environmental traits. In this study, by using blotchy mice as a model, we investigated in which extent the genetic traits in bone marrow affect the development of aortic aneurysm and rupture under the same environmental influence (high-fat diet + angiotensin II treatment) using a well-accepted model. Our results hint that the genetic traits in bone marrow alone had limited effects to influence the progression of this aortic disease in our model. The result from this study is also helping to evaluate any bone marrow–related management issue, such as inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an AHA National Scientist Development Grant (0835268N). The lipid profile service from the Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center of the University of Cincinnati was supported by NIH U24 DK059630. The authors thank Dr. Hong Lu for helping to establish the vascular histology techniques for examining murine aortic aneurysms and to discuss the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goka TJ, Stevenson RE, Hefferan PM, Howell RR. Menkes disease: a biochemical abnormality in cultured human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:604–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.2.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riordan JR, Jolicoeur-Paquet L. Metallothionein accumulation may account for intracellular copper retention in Menkes' disease. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:4639–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg GJ, Kroon JJ, Wijburg FA, et al. Muscle cell cultures in Menkes' disease: copper accumulation in myotubes. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1990;13:207–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01799687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afton SE, Caruso JA, Britigan BE, Qin Z. Copper egress is induced by PMA in human THP-1 monocytic cell line. Biometals. 2009;22:531–9. doi: 10.1007/s10534-009-9210-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HW, Chan Q, Afton SE, et al. Human macrophage ATP7A is localized in the trans-Golgi apparatus, controls intracellular copper levels, and mediates macrophage responses to dermal wounds. Inflammation. 2012;35:167–75. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9302-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly EJ, Palmiter RD. A murine model of Menkes disease reveals a physiological function of metallothionein. Nat Genet. 1996;13:219–22. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutsenko S, Barnes NL, Bartee MY, Dmitriev OY. Function and regulation of human copper-transporting ATPases. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1011–46. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips M, Camakaris J, Danks DM. A comparison of phenotype and copper distribution in blotchy and brindled mutant mice and in nutritionally copper deficient controls. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1991;29:11–29. doi: 10.1007/BF03032670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt DM. Catecholamine biosynthesis and the activity of a number of copper-dependent enzymes in the copper deficient mottled mouse mutants. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1977;57:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(77)90082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt DM, Johnson DR. An inherited deficiency in noradrenaline biosynthesis in the brindled mouse. J Neurochem. 1972;19:2811–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb03818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rezek DL, Moore CL. Depletion of brain mitochondria cytochrome oxidase in the mottled mouse mutant. Exp Neurol. 1986;91:640–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe DW, McGoodwin EB, Martin GR, Grahn D. Decreased lysyl oxidase activity in the aneurysm-prone, mottled mouse. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:939–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starcher BC, Madaras JA, Tepper AS. Lysyl oxidase deficiency in lung and fibroblasts from mice with hereditary emphysema. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;78:706–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin Z, Itoh S, Jeney V, et al. Essential role for the Menkes ATPase in activation of extracellular superoxide dismutase: implication for vascular oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2006;20:334–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4564fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin Z, Gongora MC, Ozumi K, et al. Role of Menkes ATPase in angiotensin II-induced hypertension: a key modulator for extracellular superoxide dismutase function. Hypertension. 2008;52:945–51. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudhahar V, Urao N, Oshikawa J, et al. Copper transporter ATP7A protects against endothelial dysfunction in type 1 diabetic mice by regulating extracellular superoxide dismutase. Diabetes. 2013;62:3839–50. doi: 10.2337/db12-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlief ML, Craig AM, Gitlin JD. NMDA receptor activation mediates copper homeostasis in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:239–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White C, Lee J, Kambe T, et al. A role for the ATP7A copper-transporting ATPase in macrophage bactericidal activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33949–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.070201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin Z, Konaniah ES, Neltner B, et al. Participation of ATP7A in macrophage mediated oxidation of LDL. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1471–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M003426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashino T, Sudhahar V, Urao N, et al. Unexpected role of the copper transporter ATP7A in PDGF-induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res. 2010;107:787–99. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samimi G, Safaei R, Katano K, et al. Increased expression of the copper efflux transporter ATP7A mediates resistance to cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin in ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4661–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owatari S, Akune S, Komatsu M, et al. Copper-transporting P-type ATPase, ATP7A, confers multidrug resistance and its expression is related to resistance to SN-38 in clinical colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4860–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wesenberg RL, Gwinn JL, Barnes GR., Jr Radiological findings in the kinky-hair syndrome. Radiology. 1969;92:500–6. doi: 10.1148/92.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danks DM, Campbell PE, Stevens BJ, et al. Menkes's kinky hair syndrome. An inherited defect in copper absorption with widespread effects. Pediatrics. 1972;50:188–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh S, Bresnan MJ. Menkes kinky-hair syndrome. (Trichopoliodystrophy). Low copper levels in the blood, hair, and urine. Am J Dis Child. 1973;125:572–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1973.04160040072015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin JJ, Flament-Durand J, Farriaux JP, et al. Menkes kinky-hair disease. A report on its pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 1978;42:25–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01273263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grange DK, Kaler SG, Albers GM, et al. Severe bilateral panlobular emphysema and pulmonary arterial hypoplasia: unusual manifestations of Menkes disease. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;139A:151–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adaletli I, Omeroglu A, Kurugoglu S, et al. Lumbar and iliac artery aneurysms in Menkes' disease: endovascular cover stent treatment of the lumbar artery aneurysm. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:1006–9. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-1488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mentzel HJ, Seidel J, Vogt S, et al. Vascular complications (splenic and hepatic artery aneurysms) in the occipital horn syndrome: report of a patient and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29:19–22. doi: 10.1007/s002470050526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Figueiredo Borges L, Martelli H, Fabre M, et al. Histopathology of an iliac aneurysm in a case of Menkes disease. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;13:247–51. doi: 10.2350/08-08-0516.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godwin SC, Shawker T, Chang B, Kaler SG. Brachial artery aneurysms in Menkes disease. J Pediatr. 2006;149:412–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernhard MK, Merkenschlager A, Mayer T, et al. The spectrum of neuroradiological features in Menkes disease: widening of the cerebral venous sinuses. J Pediatr Neuroradiol. 2012;1:121–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danks DM, Campbell PE, Walker-Smith J, et al. Menkes' kinky-hair syndrome. Lancet. 1972;1:1100–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)91433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheeler EM, Roberts PF. Menkes's steely hair syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:269–74. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.4.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daish P, Wheeler EM, Roberts PF, Jones RD. Menkes's syndrome. Report of a patient treated from 21 days of age with parenteral copper. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:956–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.53.12.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jankov RP, Boerkoel CF, Hellmann J, et al. Lethal neonatal Menkes' disease with severe vasculopathy and fractures. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:1297–300. doi: 10.1080/080352598750031013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaler SG, Westman JA, Bernes SM, et al. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with gastric polyps in Menkes disease. J Pediatr. 1993;122:93–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83496-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oakes BW, Danks DM, Campbell PE. Human copper deficiency: ultrastructural studies of the aorta and skin in a child with Menkes' syndrome. Exp Mol Pathol. 1976;25:82–98. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(76)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews EJ, White WJ, Bullock LP. Spontaneous aortic aneurysms in blotchy mice. Am J Pathol. 1975;78:199–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brophy CM, Tilson JE, Braverman IM, Tilson MD. Age of onset, pattern of distribution, and histology of aneurysm development in a genetically predisposed mouse model. J Vasc Surg. 1988;8:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel OV, Wilson WB, Qin Z. Production of LPS-induced inflammatory mediators in murine peritoneal macrophages: neocuproine as a broad inhibitor and ATP7A as a selective regulator. Biometals. 2013;26:415–25. doi: 10.1007/s10534-013-9624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay ME, Dietz HC. Lessons on the pathogenesis of aneurysm from heritable conditions. Nature. 2011;473:308–16. doi: 10.1038/nature10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Charo IF, et al. Angiotensin II infusion promotes ascending aortic aneurysms: attenuation by CCR2 deficiency in apoE−/− mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010;118:681–9. doi: 10.1042/CS20090372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faugeroux J, Nematalla H, Li W, et al. Angiotensin II promotes thoracic aortic dissections and ruptures in Col3a1 haploinsufficient mice. Hypertension. 2013;62:203–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moltzer E, Essers J, van Esch JHM, et al. The role of the renin–angiotensin system in thoracic aortic aneurysms: clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:441–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishibashi M, Egashira K, Zhao Q, et al. Bone marrow–derived monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 is critical in angiotensin II–induced acceleration of atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:e174–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143384.69170.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang EHC, Shvartz E, Shimizu K, et al. Deletion of EP4 on bone marrow–derived cells enhances inflammation and angiotensin II–induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:261–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.La Fontaine S, Firth SD, Lockhart PJ, et al. Intracellular localization and loss of copper responsiveness of Mnk, the murine homologue of the Menkes protein, in cells from blotchy (Moblo) and brindled (Mobr) mouse mutants. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1069–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Das S, Levinson B, Vulpe C, et al. Similar splicing mutations of the Menkes/mottled copper-transporting ATPase gene in occipital horn syndrome and the blotchy mouse. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:570–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uchida HA, Poduri A, Subramanian V, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator deficiency in bone marrow–derived cells augments rupture of angiotensin II–induced abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2845–52. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gongora MC, Qin Z, Laude K, et al. Role of extracellular superoxide dismutase in hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;48:473–81. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000235682.47673.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lam D, Harris D, Qin Z. Inflammatory mediator profiling reveals immune properties of chemotactic gradients and macrophage mediator production inhibition during thiogly-collate elicited peritoneal inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:931562. doi: 10.1155/2013/931562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zavitz CCJ, Bauer CMT, Gaschler GJ, et al. Dysregulated macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 expression drives illness in bacterial superinfection of influenza. J Immunol. 2010;184:2001–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blumberg H, Dinh H, Trueblood ES, et al. Opposing activities of two novel members of the IL-1 ligand family regulate skin inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2603–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camargo JF, Quinones MP, Mummidi S, et al. CCR5 expression levels influence NFAT translocation, IL-2 production, and subsequent signaling events during T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol. 2009;182:171–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mann JR, Camakaris J, Francis N, Danks DM. Copper metabolism in mottled mouse (Mus musculus) mutants. Studies of blotchy (Moblo) mice and a comparison with brindled (Mobr) mice. Biochem J. 1981;196:81–8. doi: 10.1042/bj1960081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qin Z, Lai B, Landero J, Caruso JA. Coupling transmission electron microscopy with synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence microscopy to image vascular copper. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2012;19:1043–9. doi: 10.1107/S090904951203405X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qin Z, Toursarkissian B, Lai B. Synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence microscopy reveals a spatial association of copper on elastic laminae in rat aortic media. Metallomics. 2011;3:823–8. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00033k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allaire E, Forough R, Clowes M, et al. Local overexpression of TIMP-1 prevents aortic aneurysm degeneration and rupture in a rat model. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1413–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuaz-Perolin C, Jguirim I, Larigauderie G, et al. Apolipoprotein E knockout mice over-expressing human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 are protected against aneurysm formation but not against atherosclerotic plaque development. J Vasc Res. 2006;43:493–501. doi: 10.1159/000095309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lemaître V, Soloway PD, D'Armiento J. Increased medial degradation with pseudo-aneurysm formation in apolipo-protein E–knockout mice deficient in tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1. Circulation. 2003;107:333–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044915.37074.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sarafi MN, Garcia-Zepeda EA, MacLean JA, et al. Murine monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-5: a novel CC chemokine that is a structural and functional homologue of human MCP-1. J Exp Med. 1997;185:99–110. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoh BL, Hosaka K, Downes DP, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 promotes inflammatory vascular repair of murine carotid aneurysms via a macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and macrophage inflammatory protein-2–dependent pathway. Circulation. 2011;124:2243–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.036061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qin Z. The use of THP-1 cells as a model for mimicking the function and regulation of monocytes and macrophages in the vasculature. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ziche M, Jones J, Gullino PM. Role of prostaglandin E1 and copper in angiogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;69:475–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raju KS, Alessandri G, Ziche M, Gullino PM. Ceruloplasmin, copper ions, and angiogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;69:1183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan X, Zhang Y, Wang L. Hussain MM Diurnal regulation of MTP and plasma triglyceride by CLOCK is mediated by SHP. Cell Metab. 12:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chaudiere J, Derouette JC, Mendy F, et al. In vitro preparation of elastin-triglyceride complexes: fatty acid uptake and modification of the susceptibility to elastase action. Atherosclerosis. 1980;36:183–94. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(80)90227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]