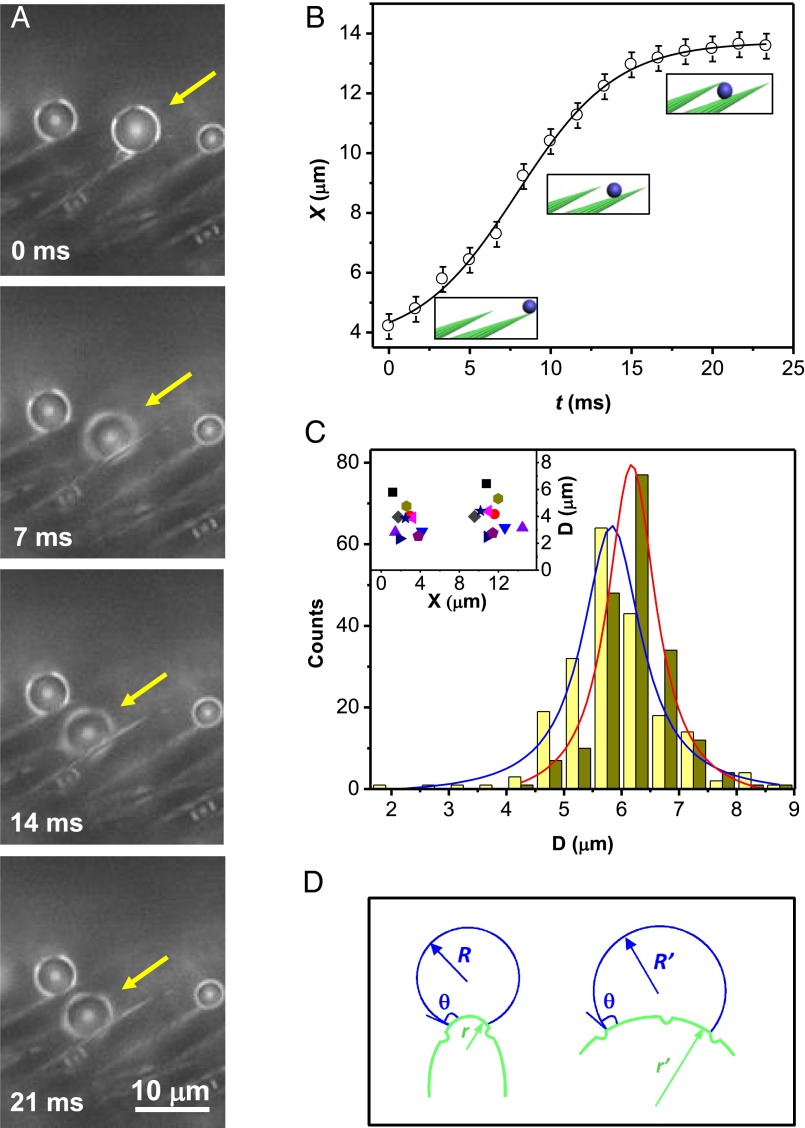

Fig. 2.

Droplets self-propelling along single conical setae (step 1). (A) As a strider leg is exposed to a fog, tiny droplets first condense at the tip of setae, before spontaneously moving toward their base. We follow the drop pointed out by a yellow arrow, and observe that it self-propels and sinks within the texture by 10 μm in less than 20 ms. Corresponding movie is Movie S2. (B) Typical plot of droplet position X as a function of time t: Water travels by a distance comparable to the seta length at a roughly constant velocity (around 0.5 mm/s) before stopping. Origin of X is chosen at the seta tip. (C) Statistics of 200 self-propelling droplets, of diameter ranging from 2 to 9 μm. Their average sizes at beginning and end of motion are 5.7 ± 0.9 μm (in blue) and 6.2 ± 0.9 μm (in red), respectively. (Inset) The diameter and position of 10 droplets (each one designated by a symbol) before and after moving confirm that drops generally do not coalesce with others, but just move individually along setae and stop at a well-defined position, typically 10–15 μm away from the seta tip. (D) For a droplet at the surface of a single seta, the conical geometry provides an asymmetric surface energy landscape, which generates a motion (see text).