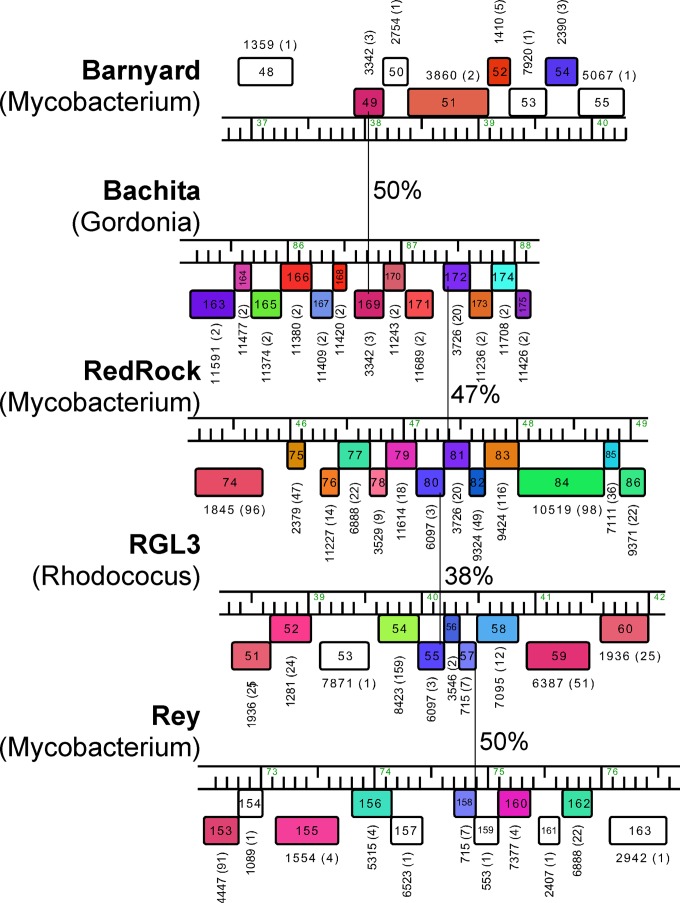

FIG 1.

Mosaic relationships among actinobacteriophages. Segments of five actinobacteriophage genomes are shown, with predicted genes represented as colored boxes (with gene numbers inside the boxes) transcribed either rightwards (shown above the genome) or leftwards (shown below the genome). Each of the 109,120 genes in a database (Actino_Draft, which contains 1,050 actinobacteriophage genomes) was assembled into phamilies (phams) of related genes in the program Phamerator; the Pham designation is shown above or below each gene, with the number of phamily members in parentheses. Vertical lines (with percent amino acid identity of their gene products) indicate genes that are related (members of the same Pham) but in different genomic contexts, illustrating the mosaic nature of phage genome architectures, which presumably occurred through a series of illegitimate recombination events. Thus, Barnyard gp49 (gene product 49) shares 50% amino acid identity with Bachita gp169, but the flanking genes are unrelated. Similar relationships between Bachita gp172 and Redrock gp81 (47% amino acid [aa] identity), between Redrock gp80 and RGL3 gp55 (38% aa identity), and between RGL3 gp57 and Rey gp158 (50% aa identity) are indicated. Interestingly, these relationships span phages isolated on hosts of different bacterial genera (as indicated in parentheses below the phage name). Note that the genes encoding these products and many of the surrounding genes are small (e.g., RGL3 57 is only 48 codons), and all are of unknown function with the exceptions of RGL3 gp53 and RGL3 gp59, which have predicted DinB-like and antirestriction functions, respectively.