Abstract

Phytochromes are red/far-red photoreceptors that play essential roles in diverse plant morphogenetic and physiological responses to light. Despite their functional significance, phytochrome diversity and evolution across photosynthetic eukaryotes remain poorly understood. Using newly available transcriptomic and genomic data we show that canonical plant phytochromes originated in a common ancestor of streptophytes (charophyte algae and land plants). Phytochromes in charophyte algae are structurally diverse, including canonical and non-canonical forms, whereas in land plants, phytochrome structure is highly conserved. Liverworts, hornworts and Selaginella apparently possess a single phytochrome, whereas independent gene duplications occurred within mosses, lycopods, ferns and seed plants, leading to diverse phytochrome families in these clades. Surprisingly, the phytochrome portions of algal and land plant neochromes, a chimera of phytochrome and phototropin, appear to share a common origin. Our results reveal novel phytochrome clades and establish the basis for understanding phytochrome functional evolution in land plants and their algal relatives.

Phytochromes are red-light photoreceptors in plants that regulate key life cycle processes, yet their evolutionary origins are not well understood. Using transcriptomic and genomic data, Li et al. find that canonical plant phytochromes originated in a common ancestor of land plants and charophyte algae.

Phytochromes are red-light photoreceptors in plants that regulate key life cycle processes, yet their evolutionary origins are not well understood. Using transcriptomic and genomic data, Li et al. find that canonical plant phytochromes originated in a common ancestor of land plants and charophyte algae.

Plants use an array of photoreceptors to measure the quality, quantity and direction of light, in order to respond to ever-changing light environments1. Four photoreceptor gene families—the phytochromes, phototropins, Zeitlupes and cryptochromes—along with UVR8, together regulate the majority of developmental and physiological processes mediated by Ultraviolet B and visible light1,2.

Phytochromes are red/far-red light sensors, particularly prominent for their control of seed germination, seedling photomorphogenesis, shade avoidance, dormancy, circadian rhythm, phototropism and flowering1,3,4. Because of their biological significance, phytochromes have been a major focus in plant research. Phytochrome photochemistry, function and its associated signal transduction mechanisms have been investigated extensively, mostly using the model flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana1,3,4,5.

Canonical plant phytochromes comprise an N-terminal photosensory core module (PCM) and a C-terminal regulatory module3,4. The PCM contains three conserved domains in the linear sequence Per/Arnt/Sim (PAS), cGMP phosphodiesterase/adenylate cyclase/FhlA (GAF) and phytochrome (PHY). It is essential for light reception and photoconversion between reversible conformations that absorb maximally in the red (650–670 nm) or far-red (705–740 nm) regions of the spectrum, referred to as Pr and Pfr, respectively. The C-terminal module consists of a PAS–PAS repeat followed by a histidine kinase-related domain. The histidine kinase-related domain resembles a histidine kinase domain but lacks the conserved histidine phosphorylation site, exhibiting serine/threonine kinase activity instead6,7.

Plant phytochromes occur as a small nuclear-encoded gene family, and in seed plants they fall into three distinct clades: PHYA, PHYB/E and PHYC8. The phylogenetic relationships among these clades are well resolved, allowing for the formulation of functional hypotheses for seed-plant phytochromes based on their orthology with Arabidopsis phytochromes8. Phytochrome diversity in non-seed plants, however, is very poorly understood, with the limited available data being derived from the Physcomitrella (moss) and Selaginella (lycophyte) genome projects9,10, and a few cloning studies11,12,13,14,15. The lack of a comprehensive phytochrome evolutionary framework for all land plants is an obstacle to understanding the evolution of phytochrome functional diversity, and makes it difficult, for example, to interpret correctly results from comparisons of function in A. thaliana and Physcomitrella patens.

An especially remarkable plant phytochrome derivative is neochrome, a chimeric photoreceptor combining a phytochrome PCM and a blue light-sensing phototropin16. Neochromes have been detected only in zygnemetalean algae, ferns and hornworts17,18. While it has been shown that the phototropin component of neochromes has two independent origins (one in zygnemetalean algae and the other in hornworts)18, the ancestry of the phytochrome portion remains unclear.

In addition to plants, phytochromes are present in prokaryotes, fungi and several protistan and algal lineages19,20. These phytochromes share with canonical plant phytochromes the PCM domain architecture at the N-terminal, but they differ in their C-terminal regulatory modules. Prokaryotic and fungal phytochromes, for example, lack the PAS–PAS repeat, and have a functional histidine kinase domain with the conserved histidine residue. Recently, Rockwell et al.20 and Duanmu et al.21 examined the phytochromes in several algal lineages (brown algae, cryptophytes, glaucophytes and prasinophytes), and discovered that some of them not only exhibit great spectral diversity, but also have novel domain combinations within the C-terminal module. Despite these important findings, phytochromes remain unreported from the majority of algal lineages. Duanmu et al.21 proposed that the canonical plant phytochrome may have originated among charophyte algae, but they were unable to confirm this.

In this study, we investigated newly available genomic and transcriptomic resources to discover phytochrome homologues outside of seed plants. We examined a total of 300 genomes and transcriptomes from seed plants, ferns, lycophytes, bryophytes, charophytes, chlorophytes and prasinophytes (all in Viridiplantae), and from other plastid-bearing algal lineages, the glaucophytes, cryptophytes, rhodophytes, haptophytes and stramenopiles. We used these data to reconstruct the first detailed phytochrome phylogeny for the eukaryotic branches of the tree of life, and to map all the major gene duplication events and domain architecture transitions onto this evolutionary tree. We uncover new phytochrome lineages and reveal that the canonical plant phytochromes originated in an ancestor of streptophytes (charophyte algae and land plants).

Results

Phytochrome phylogenetic reconstructions

We discovered a total of 350 phytochrome homologues in 148 transcriptome assemblies and 12 whole-genome sequences (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) spanning extant plant and algal diversity. In the remaining 140 assemblies and genome sequences, we detected no phytochrome homologues. We inferred a phytochrome phylogeny from an amino acid matrix that included the sequences we discovered, together with previously published sequences from GenBank. To improve our understanding of phytochrome and neochrome evolution, especially within ferns and bryophytes, we also assembled three nucleotide matrices. The fern and bryophyte matrices included 113 and 97 phytochrome sequences, respectively. The neochrome matrix included 16 neochromes and 95 phytochromes from selected bryophytes and charophytes.

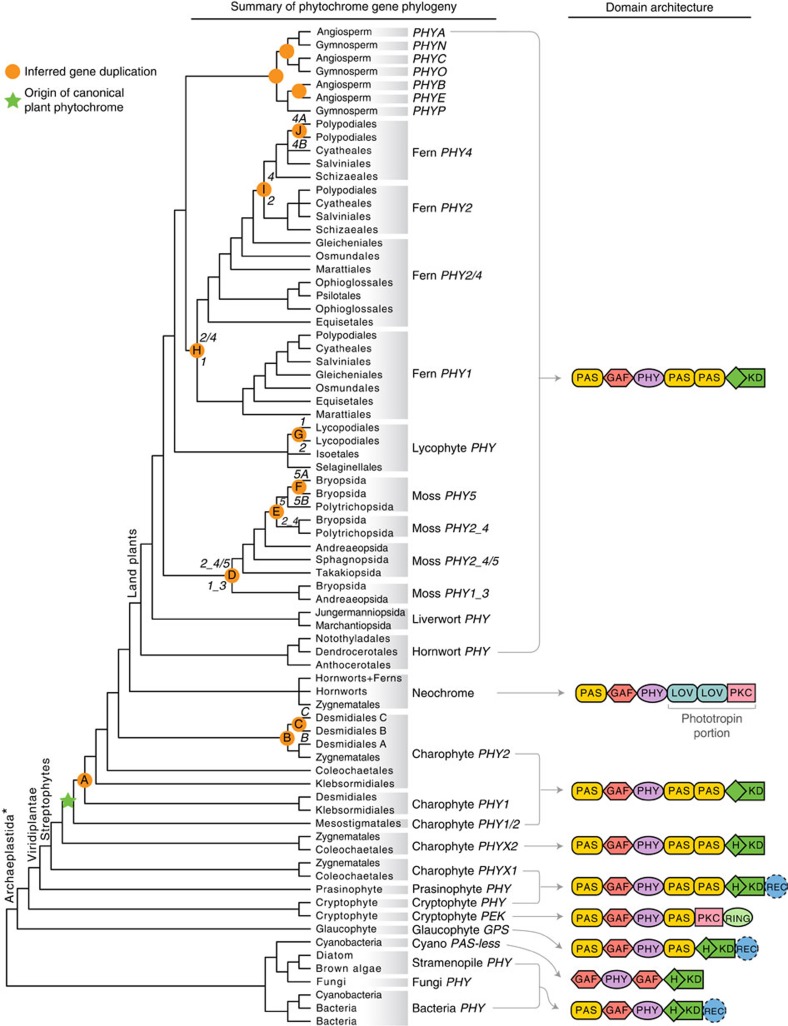

The topologies of our phytochrome gene trees correspond well with published organismal relationships22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, allowing us to pinpoint the phylogenetic positions of gene duplication events and delineate novel phytochrome clades. Below we report results on phytochrome diversity, phylogenetic structure and domain architecture in the stramenopiles, cryptophytes and Archaeplastida (or ‘Plantae': red algae+glaucophytes+Viridiplantae)32.

Names for phytochrome gene lineages

The high diversity of phytochromes we discovered in charophytes, mosses and ferns—resulting from multiple, independent gene duplications—demanded a sensible system for naming the gene lineages. Within each major organismal group of Archaeplastida (except seed plants, where a system for naming PHY has already been well established), we used numerical labels for the phytochrome clades that resulted from major gene duplication events (for example, fern PHY1-4 and charophyte PHY1-2). Subclades resulting from more local duplications were then named alphabetically within clades (for example, Polypodiales PHY4A-B and Desmidiales PHY2A-C). It should be stressed that this alphanumeric system does not imply orthology across organismal groups; for example fern PHY1 has a lower degree of relatedness to charophyte PHY1 than to fern PHY2. Charophyte PHYX1 and PHYX2 were so named here because they are not canonical plant phytochromes like charophyte PHY1-2, and their evolutionary origin is less clear. For phytochromes in glaucophytes, we adopted the term glaucophyte phytochrome sensors (GPS) of Rockwell et al.20, and for the cryptophyte phytochromes with C-terminal serine/threonine kinase, we followed Duanmu et al.21 and called them phytochrome eukaryotic kinase hybrids (PEK).

Stramenopiles and haptophytes

Stramenopiles are a large eukaryotic clade that includes brown algae (such as kelps), golden algae and diatoms, the latter being an important component of plankton. Within this group, phytochromes are known so far only from brown algae, some of their viruses and diatoms. Their sequences form a clade that is sister to fungal phytochromes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, the phytochrome from the brown algal virus EsV-1 (ref. 33) does not group with brown algae phytochromes, but instead is more closely related to those of diatoms. This relationship was not supported in a bootstrapping analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2); it was, however, also obtained by Duanmu et al.21 (but without support). Additional phytochrome data from stramenopiles will be necessary to clarify the origin of these viral phytochromes. We also examined haptophytes, a predominantly marine lineage of phytoplankton (their relationships with stramenopiles and other protists are unclear27,28). No phytochrome could be found in the haptophyte transcriptomes.

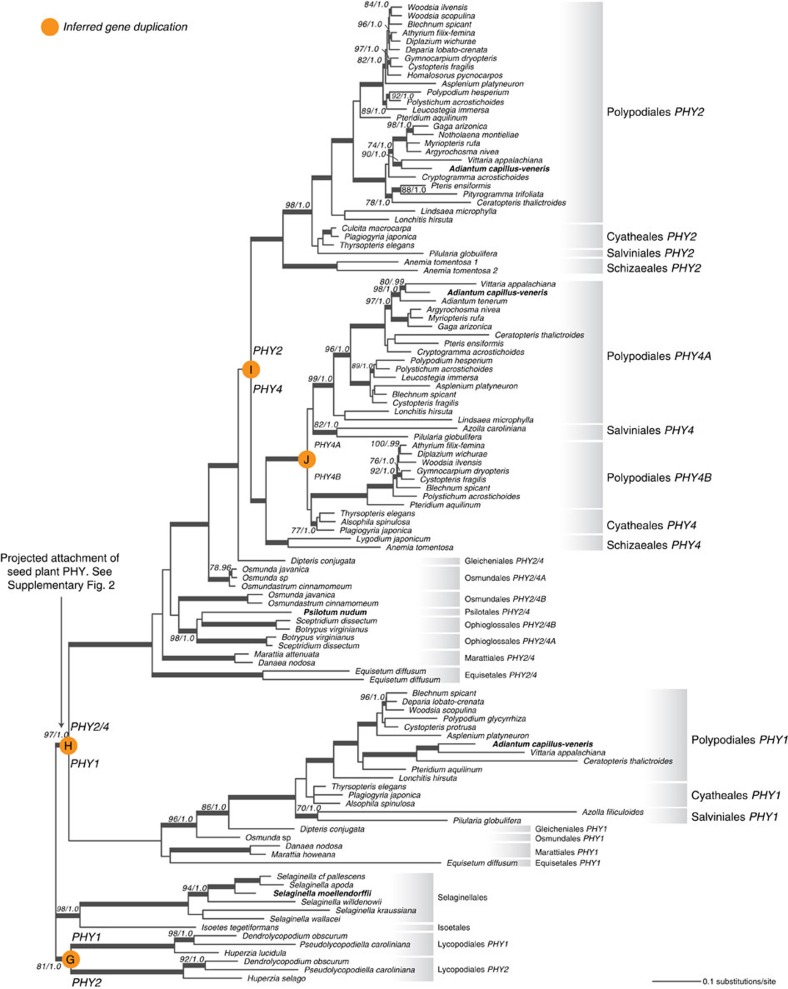

Figure 1. Phylogeny of phytochromes.

Terminal clades are collapsed into higher taxonomic units (usually orders or classes) for display purposes. Orange circles indicate inferred gene duplications. Italicized capital letters within each circle correspond to duplication events mentioned in the text, and the numbers/letters adjacent to each orange circle are the names of gene duplicates. Canonical plant phytochromes originated in an ancestor of streptophytes (green star), and some charophyte algae retain non-canonical phytochromes (PHYX1 and PHYX2). Phytochrome domain architectures are shown on the right. Domains that are not always present are indicated by dashed outlines. Domain names: GAF (cGMP phosphodiesterase/adenylate cyclase/FhlA); H/KD (histidine phosphorylation site (H) in the histidine kinase domain (KD)); PAS (Per/Arnt/Sim); PHY (Phytochrome); PKC (Protein Kinase C); REC (Response Regulator); and RING (Really Interesting New Gene). *Traditional Archaeplastida do not include cryptophytes32.

Red algae

Red algae are mostly multicellular, marine species that include many coralline reef-building algae. No phytochromes were found in the 28 red algal transcriptomes we examined, nor in the published genomes of Porphyridium purpureum, Chondrus crispus, Cyanidioschyzon merolae, Galdieria sulphuraria and Pyropia yezoensis (Supplementary Table 1). This result, based on data from all Rhodophyta classes34, provides compelling evidence for the absence of phytochromes from red algae (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Glaucophytes

Glaucophytes are a small clade of freshwater, unicellular algae with unusual plastids referred to as cyanelles, which, unlike plastids in rhodophytes and green plants, retain a peptidoglycan layer35. Phytochromes are present in glaucophytes (GPS20), and when our tree is rooted on the branch to prokaryote/fungus/stramenopile phytochromes, GPS are resolved as sister to cryptophyte+Viridiplantae phytochromes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). GPS, in contrast with canonical plant phytochromes, have a single PAS domain in the C-terminal module, and the conserved histidine residue is present in the kinase domain, suggesting it retains histidine kinase activity21.

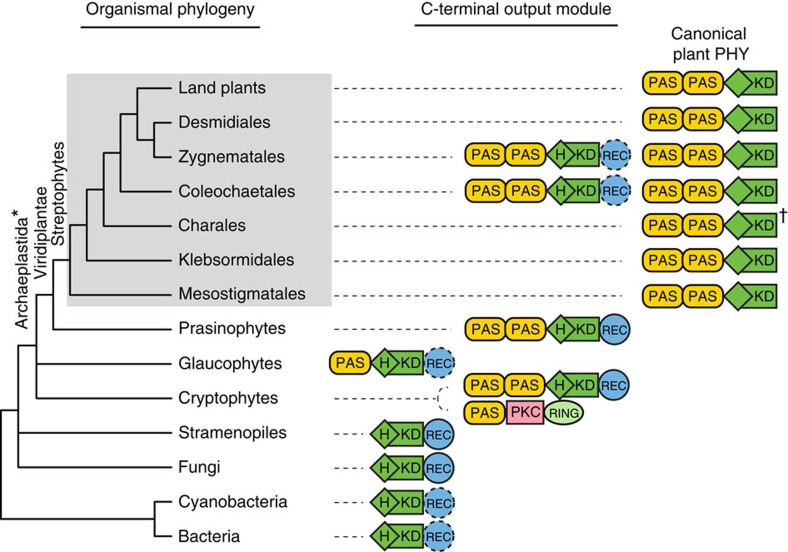

Cryptophytes

The phylogenetic position of cryptophytes remains controversial. They were once thought to be related to stramenopiles and haptophytes (belonging to the kingdom Chromalveolata), but some recent phylogenomic studies place them either as nested within, or sister to, Archaeplastida26,27,28. In our analyses, cryptophyte+Viridiplantae phytochromes form a clade that is sister to glaucophyte phytochromes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Also, phytochromes from Viridiplantae and from some cryptophytes share the characteristic PAS–PAS repeat in the C terminus (Fig. 2). These cryptophyte phytochromes differ from the canonical phytochromes in their retention of the conserved histidine phosphorylation site in the kinase domain (Figs 1 and 2). Some cryptophyte phytochromes do not have the PAS–PAS repeat in the C terminus, but instead possess a single PAS followed by a serine/threonine kinase domain (‘PKC' in Figs 1 and 2). Despite this variation in the C terminus, the N-terminal photosensory modules of all cryptophyte phytochromes are monophyletic (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The diversity and evolution of phytochrome C-terminal output module.

The tree depicts the organismal phylogeny of all the phytochrome-containing lineages. The domain architecture of the C-terminal regulatory module characteristic of each lineage is indicated on the right connected by dashed lines. The N-terminal photosensory module has a largely conserved domain sequence of PAS–GAF–PHY, and is not drawn here. The substitution of the histidine phosphorylation site (H) in the histidine kinase domain (KD) occurred subsequent to the divergence of prasinophytes. The canonical plant phytochrome is restricted to streptophytes (in grey box); Zygnematales and Coleochaetales also have non-canonical plant phytochromes. Domain names: PAS (Per/Arnt/Sim); PKC (Protein Kinase C); REC (Response Regulator); and RING (Really Interesting New Gene). *Traditional Archaeplastida do not include cryptophytes32. †Full-length phytochrome was not available from Charales and its domain structure was inferred.

Viridiplantae

Viridiplantae comprise two lineages, Chlorophyta and Streptophyta. Chlorophyta include chlorophytes (Trebouxiophyceae+Ulvophyceae+Chlorophyceae+Pedinophyceae) and prasinophytes (Supplementary Fig. 1). Chlorophytes appear to lack phytochromes entirely; we did not find homologues in any of the chlorophyte transcriptomes examined, including 14 Trebouxiophyceae, 21 Ulvophyceae, 59 Chlorophyceae and 2 Pedinophyceae. This result is consistent with available whole-genome sequence data; the genomes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Volvox carteri and Chlorella variabilis (Chlorophyceae) lack phytochromes. Prasinophytes, on the other hand, do have phytochromes. Most of these have a PAS–PAS repeat, a histidine kinase domain, and a response regulator domain at the C terminus21. Prasinophyte phytochromes are monophyletic and are the sister group to streptophyte phytochromes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Streptophyta (or streptophytes) are an assemblage of the charophytes (a paraphyletic grade of algae) and the land plants22 (Supplementary Fig. 1). We found phytochrome homologues in all land plant clades, as well as in all charophyte lineages: Mesostigmatales (including Chlorokybales), Klebsormidiales, Coleochaetales, Charales, Zygnematales and Desmidiales (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The Charales phytochromes were not included in our final phylogenetic analyses because the transcriptome contigs (and also the data currently available on GenBank) are too short to be informative about their relationships. All streptophytes have canonical plant phytochromes, including Mesostigmatales, the earliest diverging charophyte lineage (Figs 1 and 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). This result suggests that the origin of the canonical plant phytochrome took place in the ancestor of extant streptophytes.

Within charophyte algae we identified several gene duplication events. We infer one duplication to have occurred after Mesostigmatales diverged (‘A' in Fig. 1), resulting in two clades: one is small and charophyte specific (charophyte PHY1), whereas the other is large and includes charophyte PHY2, and the land plant phytochromes. Members of the charophyte PHY1 clade are not common in our algal transcriptomes, and were found only in Desmidiales and in Entransia of the early-diverging Klebsormidiales (Supplementary Fig. 2). On the other hand, the charophyte PHY2 homologue is found consistently across algal transcriptomes. It experienced additional duplications (‘B' and ‘C' in Fig. 1) that resulted in three phytochrome subclades within Desmidiales (Desmidiales PHY2A-C). Relationships recovered within each of these phytochrome subclades correspond well to species phylogenies for Desmidiales25.

We found that Zygnematales and Coleochaetales (charophytes) also have two non-canonical phytochrome clades (charophyte PHYX1 and PHYX2, Fig. 1). Some PHYX1 have a response regulator domain at the C terminus, similar to prasinophyte, cryptophyte and glaucophyte phytochromes (Figs 1 and 2). Intriguingly, PHYX1 lacks all the known conserved cysteine residues (CysA-D20) in the PAS–GAF region of the N terminus that bind bilin chromophores, indicating that this protein may not bind a bilin, or that a non-conserved binding site is used.

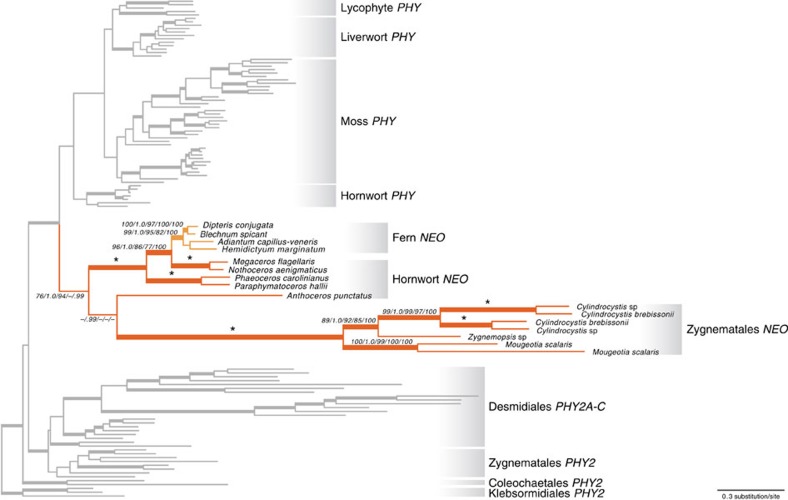

Neochromes

Our data suggest that the phytochrome module of neochrome had a single origin (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Published data indicate that the phototropin module of neochromes, in contrast, had independent origins in algae and hornworts18, implying two separate fusion events involving phytochromes that shared a common ancestor. To further explore this finding, we analysed the neochrome nucleotide data set (see above) using several nucleotide, codon and amino acid models, and performed a topology test. We consistently recovered the monophyly of the phytochrome module of neochromes, and usually with high support, from analyses using all models (Fig. 3). Although Anthoceros (a hornwort) neochrome was resolved as sister to a Zygnematales (algal) neochrome, this relationship was not supported (except in the MrBayes analysis of the nucleotide data set). We then used the Swofford–Olsen–Waddell–Hillis (SOWH) test to compare the topology with all neochromes (the phytochrome module) forming a single clade, against an alternative in which neochromes of Zygnematales were forced to not group with hornworts+ferns. The alternative hypothesis was rejected (P<0.00001), and the monophyly of the phytochrome module of neochromes was favoured.

Figure 3. Phylogeny of neochromes and phytochromes.

The support values are shown for the neochrome branches only, in the following order: maximum likelihood bootstrap support (BS) from general time reversible (GTR) nucleotide model/Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) from GTR nucleotide model/aLRT support from codon model/maximum likelihood bootstrap values from Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) amino acid model/Bayesian posterior probabilities from JTT amino acid model. ‘*' Indicates all the support values=100 or 1.0. ‘−' denotes BS<70, aLRT<70, or PP<0.95. Branches are thickened when BS>70, aLRT>70, and PP>0.95.

Bryophytes

Phytochromes from mosses, liverworts and hornworts each form a monophyletic group (Fig. 4). We detected single phytochrome homologues in hornwort and liverwort transcriptomes. The gene phylogenies match the species relationships30,31, consistent with the presence of single orthologous genes in these taxa. Indeed, a single phytochrome has been identified via cloning methods in the liverwort, Marchantia paleacea var. diptera15. We also searched the low-coverage draft genome of the hornwort Anthoceros punctatus (20X; Li et al.18) and found only one phytochrome. To further evaluate gene copy number, we hybridized the A. punctatus genomic DNA with phytochrome RNA probes, and used Illumina MiSeq to sequence the captured DNA fragments. The same phytochrome contig (and only that contig) was recovered, suggesting that this hornwort does not harbour additional, divergent phytochrome copies.

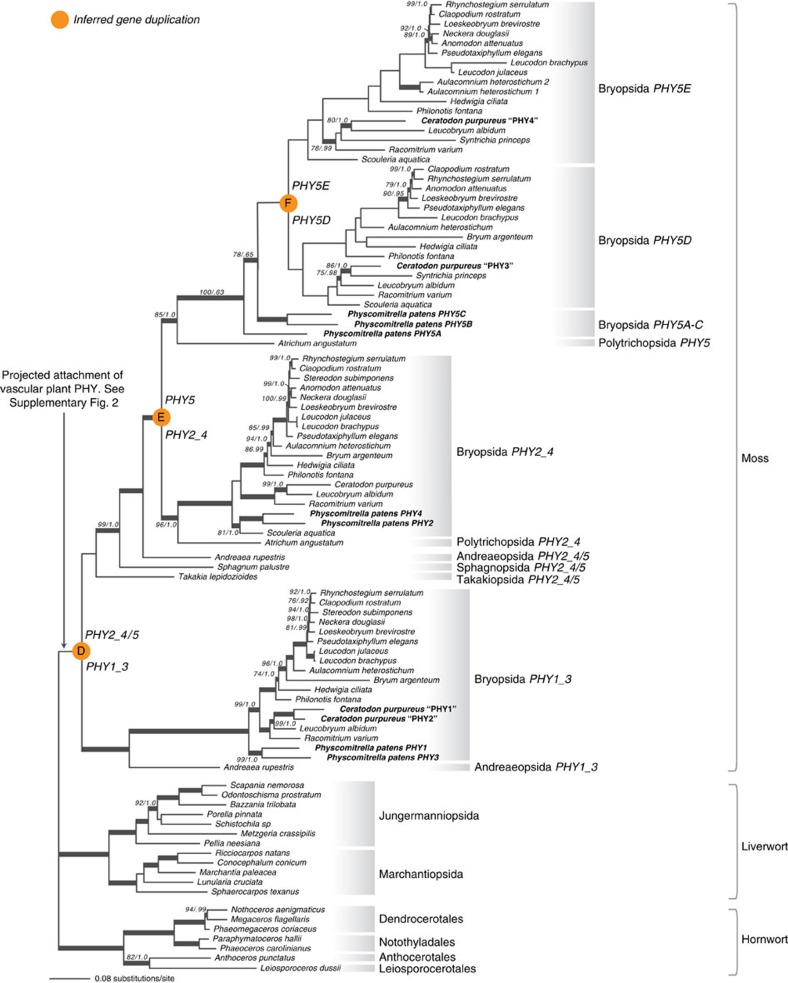

Figure 4. Phylogeny of bryophyte phytochromes.

Previously identified phytochromes are in bold font. Support values associated with branches are maximum likelihood bootstrap values (BS)/Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP); these are only displayed (along with thickened branches) if BS>70 and PP>0.95. Thickened branches without numbers are 100/1.0. The position of orange circles indicates inferred gene duplications. Italicized capital letters within each circle correspond to the duplication event mentioned in the text, and the numbers/letters adjacent to each circle indicate the names of the gene duplicates.

In contrast, phytochromes in mosses are diverse, with at least four distinct clades resulting from three gene duplications (Fig. 4). The phylogeny reveals those moss phytochromes that are orthologous to the previously named P. patens phytochromes, PpPHY1–5. The Physcomitrella phytochromes and their orthologs form the following clades: moss PHY1_3 (including PpPHY1 and PpPHY3), moss PHY2_4 (including PpPHY2 and PpPHY4), and moss PHY5 (including PpPHY5A–C). An ancient duplication (‘D' in Fig. 4) gave rise to moss PHY1_3 and moss PHY2_4+PHY5 clades. The timing of this duplication is dependent on the phylogenetic position of the Takakia phytochrome, resolved here as sister to the moss PHY2_4+PHY5 clade, but without support (Fig. 4). Because Takakia (Takakiopsida) represents the earliest diverging lineage in the moss species phylogeny36, the first phytochrome duplication probably predates the origin of all extant mosses. In the moss PHY2_4+PHY5 clade, another duplication (‘E' in Fig. 5) occurred following the split of Andreaea (Andreaeopsida) but before Atrichum (Polytrichopsida) diverged, separating moss PHY2_4 and PHY5. The moss PHY5 clade had an additional duplication (‘F' in Fig. 4), probably after Physcomitrella diverged, that resulted in moss PHY5D and PHY5E subclades.

Figure 5. Phylogeny of fern and lycophyte phytochromes.

Previously identified phytochromes are shown in bold. Support values associated with branches are maximum likelihood bootstrap values (BS)/Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP); these are only displayed (along with thickened branches) if BS>70 and PP>0.95. Thickened branches without numbers are 100/1.0. The position of orange circles estimates the origin of inferred gene duplications. Italicized capital letters within each circle correspond to the duplication event mentioned in the text, and the numbers/letters adjacent to each circle indicate the names of the gene duplicates.

Our results show that the phytochrome copies previously cloned from Ceratodon purpureus, which were named CpPHY1–4 (ref. 37), have the following relationships with the moss phytochromes: CpPHY1 and CpPHY2 are each others closest relatives, and are members of the moss PHY1_3 lineage; CpPHY3 and CpPHY4 are members of the moss PHY5 lineage (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the four known C. purpureus phytochromes—‘CpPHY1', ‘CpPHY2', ‘CpPHY3' and ‘CpPHY4' (Fig. 4) should be renamed to CpPHY1_3A, CpPHY1_3B, CpPHY5D and CpPHY5E, respectively, and that the novel C. purpureus phytochrome discovered here should be designated as CpPHY2_4.

Lycophytes

Lycophyte phytochromes are resolved as monophyletic and are sister to the fern plus seed-plant phytochromes (Figs 1 and 5, Supplementary Fig. 2). Selaginella and Isoetes (Isoetopsida) each have a single phytochrome, with the exception of Selaginella mollendorffii, where two nearly identical phytochromes are apparent in the whole-genome sequence data. Their high degree of similarity suggests that they might be products of a species-specific gene duplication. In contrast, Lycopodiales have two distinct phytochrome clades that we name Lycopodiales PHY1 and Lycopodiales PHY2. Because all the Lycopodiales lineages38 are represented in each phytochrome clade, we infer that the duplication of Lycopodiales PHY1/2 (‘G' in Fig. 5) predates the common ancestor of all extant Lycopodiales.

Ferns

Fern phytochromes form a clade that is sister to the seed plant phytochromes (Figs 1 and 5, Supplementary Fig. 2). Within ferns we uncovered four phytochrome clades that we designate fern PHY1, PHY2, PHY4A and PHY4B. The name PHY3 was used previously to denote the chimeric photoreceptor that is now recognized as neochrome17,18. The deep evolutionary split between the fern PHY1 and PHY2/4 clades predates the most recent ancestor of extant ferns (‘H' in Fig. 5). Fern PHY2 and PHY4 probably separated after Gleicheniales diverged (‘I' in Fig. 5), and the earliest diverging fern lineages (that is, Gleicheniales, Osmundales, Psilotales, Ophioglossales, Marattiales and Equisetales) have the pre-duplicated PHY2/4 copy. It should be noted that our broad-scale amino acid data set resolved a slightly different topology, placing Gleicheniales PHY2/4 closer to PHY4 (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the amino acid data set included fewer sequences from ferns, which could reduce phylogenetic accuracy39. It is likely that that the phylogeny (Fig. 5) inferred from rigorous analyses of nucleotide data more accurately reflects gene relationships.

We found that Ophioglossales and Osmundales each have two PHY2/4 copies, which likely arose from independent gene duplications (Fig. 5). The duplication of Ophioglossales PHY2/4A and PHY2/4B occurred either at the ancestor of Ophioglossales or of Ophioglossales+Psilotales, but the history of PHY2/4 in Osmundales is unclear. The Osmundales PHY2/4A and PHY2/4B were not resolved as monophyletic, and the phylogenetic position of Osmundales PHY2/4B is incongruent with published fern species relationships23.

After the split of fern PHY2 and PHY4, PHY4 duplicated again, giving rise to fern PHY4A and PHY4B (‘J' in Fig. 5), and both are found in Polypodiales. We cannot precisely determine the timing of this duplication event because the relationships among Polypodiales PHY4A-B, Cyatheales PHY4 and Salviniales PHY4 are resolved without support. Interestingly, PHY4A was previously known only from Adiantum capillus-veneris (as AcPHY4). Its first intron incorporated an inserted Ty3/gypsy retrotransposon and the downstream exon sequence was unknown12. We found full-length PHY4A transcripts in a wide range of Polypodiales, suggesting that PHY4A likely is functional in most other species, if not in A. capillus-veneris. PHY4B is a novel phytochrome clade that has not been documented before; it is not common in the fern transcriptomes we examined.

Seed plants

Seed plant phytochromes cluster into three clades (Supplementary Fig. 2) corresponding to PHYA, PHYB/E and PHYC, in accordance with previous studies8. Organismal relationships within the gene subclades largely are consistent with those inferred in phylogenetic studies of angiosperms40. Notably, however, support for the monophyly of gymnosperms was low. We found two divergent transcripts of PHYE in Ranunculales, represented by Aquilegia (Ranunculaceae; from whole-genome data) and Capnoides (Papaveraceae; from transcriptome data) (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that a gene duplication event occurred deep in Ranunculales; however, more extensive sampling in Ranunculales is needed to resolve the timing of this duplication.

Discussion

Our phylogenetic results refute previous hypotheses suggesting that plants acquired phytochrome from cyanobacteria via endosymbiotic gene transfer41,42, because streptophyte and cyanobacterial phytochromes are not closest relatives in our phytochrome trees (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2), a result also recently obtained by Duanmu et al.21. Instead, plant phytochromes evolved from a precursor shared with other Archaeplastida. We clearly placed the origin of canonical plant phytochromes in a common ancestor of extant streptophytes (Figs 1 and 2). Our data, moreover, show that the origin of this structure required multiple steps. The gain of the internal PAS–PAS repeat took place first, in the ancestor of Viridiplantae, or of Viridplantae+cryptophytes (Fig. 2). As noted above, the position of cryptophytes is uncertain, and its inclusion in Archaeplastida is not strongly supported in published studies26,27,28. The topology of our phytochrome trees is consistent with a sister-group relationship between Viridiplantae and cryptophytes, but the topology also could result from endosymbiotic or horizontal gene transfer. The loss of the histidine phosphorylation site in the histidine kinase domain—hence the attainment of the canonical form—occurred later, in the ancestor of streptophytes, and seems to have been accompanied by a permanent dissociation with the response regulator at the C-terminal end (Fig. 2). Some streptophytes have additional, non-canonical phytochromes. Charophyte PHYX1 and PHYX2, both found in Zygnematales and Coleochaetales, have the conserved histidine residue, and some PHYX1 also have a response regulator domain (Figs 1 and 2). The fact that charophyte PHYX1 and PHYX2 were not found in all streptophytes implies that some orthologs may have been missed in our transcriptomic and genomic scans, and/or a scenario in which duplications occurred early in streptophytes and were followed by multiple losses.

Our findings highlight the different evolutionary modes of the phytochrome N- and C-terminal modules. The N-terminal photosensory module is deeply conserved across eukaryotes and prokaryotes, and the linear domain sequence of PAS–GAF–PHY is found in the majority of known phytochromes (Fig. 1). In contrast, the evolution of the C-terminal regulatory module has been much more dynamic (Fig. 2). For example, the C-terminal PAS may be absent, may occur singly, or may occur as a tandem repeat (Fig. 3). Serine/threonine kinase or tyrosine kinase domains have also been independently recruited into the regulatory module in the cryptophyte and C. purpureus (moss) phytochromes43 (Fig. 2). The successful linkage of the phytochrome photosensory module with a variety of C-terminal modules has promoted phytochrome functional diversity. Certainly the most compelling example is that of the neochromes. It combines phytochrome and phototropin modules into a single protein to process blue and red/far-red light signals in the control of phototropism44. Neochrome was first discovered in ferns16 and postulated to be a driver of the modern fern radiation under low light, angiosperm-dominated forest canopies45,46,47. Suetsugu et al.17 later discovered a similar phytochrome–phototropin chimera in Mougeotia scalaris (zygnematalean alga), and proposed that neochrome had independently evolved twice. A recent study identified yet another neochrome from hornworts, and demonstrated that ferns acquired their neochromes from hornworts via horizontal gene transfer18. By placing the phototropin portion of neochrome into a broad phylogeny of phototropins, Li et al.18 also showed that phototropin modules of neochromes had two separate origins, once in hornworts and once in zygnematalean algae. In contrast, the phytochrome portion of neochrome has had a different evolutionary history, with Zygnematales, hornworts and ferns forming a single monophyletic group (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). This result is robust, and is supported by most of the analyses and by a topology test. Our results thus suggest that neochromes originated via two separate fusion events, involving two distinct sources of phototropin but the same phytochrome progenitor. This is a fascinating extension of the capacity and propensity of the phytochrome photosensory module to be linked with functionally distinct downstream domains.

The major clades of land plants differ markedly with respect to phytochrome gene diversity. It appears that phytochromes are single copy in most liverworts, hornworts and Isoetopsida (Isoetaceae and Selaginellaceae), whereas they have independently diversified in Lycopodiales, mosses, ferns and seed plants (Fig. 1). In ferns, a pattern of early gene duplication followed by gene losses could explain the phylogenetic positions of two Osmundales PHY2/4, which are incongruent with known species relationships in ferns (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we observed a relationship between phytochrome copy number and species richness. For instance, the polypod ferns (Polypodiales), which account for 90% of extant fern diversity47, have four phytochrome copies, whereas other species-poor fern lineages have only two or three (Fig. 5). Likewise, moss species belonging to the hyper-diverse Bryopsida—containing 95% of extant moss diversity—have experienced the highest number of phytochrome duplications compared with other bryophyte lineages (Fig. 4). It is possible that the evolution of phytochrome structural and functional diversity enhanced the ability of polypod ferns and Bryopsida mosses to adapt to diverse light environments. Indeed, seed plants, ferns and mosses each have at least one phytochrome duplicate that convergently evolved or retained the role of mediating high-irradiance responses48,49,50,51, a trait likely to be important for surviving under deep canopy shade52 (see below). This ‘phytochrome-driven species diversification' hypothesis, however, needs rigorous testing by phylogenetic comparative methods and functional studies in non-seed plants that identify the genetic bases of phytochrome functions.

The independent phytochrome diversification events in seed plants, ferns, mosses and Lycopodiales have significant implications for phytochrome functional studies. Moss phytochromes, for example, are more closely related to each other than to any of the seed-plant phytochromes (and the same is true, of course, for phytochromes from ferns and those from Lycopodiales). Seed-plant phytochromes have undergone significant differentiation into two major types. One is represented by phyA of A. thaliana, which is the primary mediator of red-light responses in deep shade and beneath the soil surface. It degrades rapidly in light, mediates very-low fluence and high-irradiance responses, and depends on protein partners FHY1 (far-red elongated hypocoytl 1) and FHL (FHY1 like) for nuclear translocation. The other is represented by phyB-E of A. thaliana, which are the primary mediators of red-light responses in open habitats. They have a longer half-life than phyA in light, mediate low-fluence responses, and in the case of phyB, nuclear translocation does not require FHY1 or FHL4,5. A similar partitioning of function has been documented in some fern and moss phytochrome duplicates49,53,54, demonstrating a case of convergent differentiation following independent gene duplications. In future studies, it would be of particular interest to infer the ancestral properties of land plant phytochrome: Did it have a short or long half-life? What kinds of physiological responses did it mediate? How was nuclear translocation executed? Studies of liverwort, hornwort and Selaginella phytochromes, which exist as a single-copy gene, could serve as ‘baseline models' for understanding the genetic basis of phytochrome functional diversification.

Recent functional studies on a small but varied set of algal phytochromes revealed a surprising degree of spectral diversity, which might reflect adaptations to a range of marine and aquatic environments20,21. For example, photoreversible phytochromes in prasinophyte algae include orange/far-red receptors as well as red/far-red receptors, and in algae outside of Viridiplantae, there also are blue/far-red and red/blue receptors21. This sharply contrasts with the very limited spectral diversity in canonical plant phytochromes, all of which are red/far-red receptors as far as is known. The novel algal phytochrome clades we detected are a potential treasure trove for discovering the steps involved during the transition from a spectrally diverse set of reversible photoreceptors to a set that is centred on the red to far-red region of the spectrum, and for the characterization of new biochemical variants. Some of these may have implications for understanding the role of phytochrome evolution in the recolonization of marine and freshwater environments by terrestrial plants.

In summary, our study has revealed that the diversity of Viridiplantae phytochromes is far greater than was realized, and points to exciting opportunities to link this structural diversity with function and ecology.

Methods

Mining transcriptomes and genomes for phytochrome homologues

The transcriptomes and genomes sampled in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. We used the Python pipeline BlueDevil following Li et al.18 to mine transcriptomes. To search the whole-genome data, we used BLASTp implemented in Phytozome55 or individual genome project portals (Supplementary Table 1). The protein domain composition of each of the phytochrome sequences was determined by querying the NCBI Conserved Domain Database56.

Sequence alignment

In addition to the phytochrome homologues mined from transcriptomes and genomes, we gathered selected Genbank accessions and a sequence cloned from Marattia howeana (voucher: S.W.Graham and S. Mathews 15, deposited in NSW; primers: 110f –5′GTNACNGCNTAYYTNCARCGNATG3′, 788r – 5′GTMACATCTTGRSCMACAAARCAYAC3′).

We assembled four sequence data sets, one was translated into an amino acid alignment and the others were analysed as nucleotide matrices. The amino acid data set included the majority of the sequences (423 sequences in total; Supplementary Fig. 2). The sequences were initially aligned using MUSCLE57, followed by manual curation of the alignment based on known domain boundaries and protein structures. We did not include regions with uncertain or no homology; these include all response regulator (REC), really interesting new gene (RING), Light-Oxygen-Voltage sensor (LOV) and PKC domains, as well as the single PAS domain in GPS. Unalignable regions were also excluded and the final alignment included 1,106 amino acid sites. The nucleotide data sets were assembled to provide higher phylogenetic resolution within fern+lycophyte phytochromes (113 sequences; Fig. 5), bryophyte phytochromes (97 sequences; Fig. 4), and neochromes (111 sequences; Fig. 3). Sequences were aligned as amino acids and then back-translated to nucleotides, and the alignment was refined by manual editing. The fern+lycophyte, and bryophyte phytochrome alignments contained 3,366 and 3,429 nucleotide sites, respectively. The neochrome alignment included only the N-terminal photosenory module (PAS–GAF–PHY domains; 1,920 nucleotide sites). All alignments are available from Dryad (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5rs50).

Phylogenetic reconstruction

For the broad-scale amino acid alignment, JTT+I+G was selected as the best-fitting empirical model by ProTest 3 under Akaike Information Criterion58. We used Garli v2.0 (ref. 59) to find the maximum likelihood tree, with ten independent runs and genthreshfortopoterm set to 100,000. The starting tree for Garli came from a RAxML v8.1.11 (ref. 60) run. To obtain bootstrap branch support values, RAxML was run with 1,000 replicates using JTT+G.

For the nucleotide alignments, we used PartitionFinder v1.1.1 (ref. 61) to infer the best partitioning schemes and substitution models, under Akaike Information Criterion. Maximum likelihood tree searching and bootstrapping (1,000 replicates) were done in RAxML. Bayesian inference was carried out in MrBayes v3.2.3 (ref. 62), with two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs and four chains each. We unlinked the substitution parameters and set the rate prior to vary among partitions. The MCMC output was inspected using Tracer63 to ensure convergence and mixing (effective sample sizes all >200); 25% of the total generations were discarded as burn-in before analyzing the posterior distribution.

Additional analyses were applied to the neochrome data set. First, we used CodonPhyML v1.0 (ref. 64) to infer the tree topology and to assess support (SH-like aLRT branch support), using a codon substitution model. Four categories of non-synonymous/synonymous substitution rate ratios were drawn from a discrete gamma distribution, and codon frequencies were estimated from the nucleotide frequencies at each codon position (F3 × 4). Second, we translated the nucleotides into amino acids, and carried out maximum likelihood tree searching and bootstrapping (in RAxML), as well as Bayesian inference (in MrBayes) under the JTT+I+G model. Finally, we used the SOWH test, implemented in SOWHAT65, to investigate whether the inferred tree topology (phytochrome portion of neochrome forming a clade) is significantly better than the alternative topology (neochrome not monophyletic). In SOWHAT, we used the default stopping criterion and applied a topological constraint forcing land plant and zygnematalean neochrome to be non-monophyletic.

To derive the organismal relationships shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1, we merged the topologies from three recent phylogenetic studies. The relationships within streptophytes and chlorophyte algae were from Wickett et al.22 and Marin29, respectively. For the broader kingdom-level relationship, we referenced the topology of Grant and Katz28.

Confirming gene copy number by target enrichment

We used a target enrichment strategy to test whether hornworts have a single phytochrome locus. In this approach, specific RNA probes are hybridized to genomic DNA to enrich the representation of particular gene fragments. Target enrichment has several advantages over the traditional Southern blotting approach. In particular, it uses thousands of different hybridization probes (rather than just a few), and the end products are not DNA bands, but actual sequence data.

We designed a total of 7,502 120-mer RNA probes to target phytochrome, phototropin and neochrome genes, with a special focus on those of hornworts and ferns (probe sequences available from Dryad http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5rs50). The probes overlap every 60 bp (a 2X tiling strategy), and were synthesized and biotin-labeled by Mycroarray. Genomic DNA of the hornwort A. punctatus was extracted using a modified hexadecyl trimethyl-ammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol, and sheared by Covaris with fragments peaking at 300 bp. Library preparation for Illumina sequencing was done using a KAPA Biosystem kit, in combination with NEBNext Multiplex Oligos. To enrich for potentially divergent homologues, we used the touchdown procedure of Li et al.66, in which the genomic DNA library and the probes were hybridized at 65 °C for 11 h followed by 60 °C (11 h), 55 °C (11 h) and 50 °C (11 h). The hybridized DNA fragments were captured by streptavidin beads and washed following the protocol of Mycroarray. The final product was pooled with nine other libraries in equimolar and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq (250 bp paired end). To process the reads, we used Scythe v0.994 (ref. 67) to remove the adapter sequences, and used Sickle v1.33 (ref. 68) to trim low-quality bases. The resulting reads were then assembled by SOAPdenovo2 (ref. 69), and the phytochrome contig was identified by BLASTn70. The raw reads were deposited in NCBI SRA (SRP055877).

Data availability

All relevant data present in this publication can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5rs50.

Additional information

Accession codes: The reads from target enrichment generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the accession code SRP055877. The phytochrome DNA sequences generated in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession codes KP872700, KT003814 to KT003816, KT013280 to KT013293 and KT071819 to KT072044.

How to cite this article: Li, F.-W. et al. Phytochrome diversity in green plants and the origin of canonical plant phytochromes. Nat. Commun. 6:7852 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8852 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-2, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant DEB-1407158 (to K.M.P and F.-W.L.), and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to F.-W.L.). We thank Meng Chen, Pryer lab members, and the Duke Systematics Discussion Group for insightful suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

Author contributions F.-W.L., K.M.P. and S.M. contributed to the design of the research approach. F.-W.L. performed the target enrichment sequencing. F.-W.L. carried out the data mining and phylogenetic analyses. F.-W.L., M.M., C.J.R., J.C.V., D.W.S., S.W.G. and G.K.-S.W. contributed transcriptome data. F.-W.L., K.M.P. and S.M. wrote the paper.

References

- Möglich A., Yang X., Ayers R. A. & Moffat K. Structure and function of plant photoreceptors. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 61, 21–47 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijde M. & Ulm R. UV-B photoreceptor-mediated signalling in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 230–237 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell N. C., Su Y.-S. & Lagarias J. C. Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 57, 837–858 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K. A. & Quail P. H. Phytochrome functions in Arabidopsis development. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 11–24 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. & Chory J. Phytochrome signaling mechanisms and the control of plant development. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 664–671 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh K. C. & Lagarias J. C. Eukaryotic phytochromes: light-regulated serine/threonine protein kinases with histidine kinase ancestry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13976–13981 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser C. Phytochromes as light-modulated protein kinases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 467–473 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S. Evolutionary studies illuminate the structural-functional model of plant phytochromes. Plant Cell 22, 4–16 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks J. A. et al. The Selaginella genome identifies genetic changes associated with the evolution of vascular plants. Science 332, 960–963 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensing S. A. et al. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 319, 64–69 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Poetsch H. A. W., Marx S., Kolukisaoglu U., Hanelt S. & Birgit B. Phytochrome evolution: phytochrome genes in ferns and mosses. Physiol. Plantarum 91, 241–250 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K., Kanegae T. & Wada M. A full length Ty3/gypsy-type retrotransposon in the fern Adiantum. J. Plant Res. 110, 495–499 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H. et al. The deduced amino acid sequence of phytochrome from Adiantum includes consensus motifs present in phytochrome B from seed plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 34, 1329–1334 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Pasentsis K., Paulo N., Algarra P., Dittrich P. & Thümmler F. Characterization and expression of the phytochrome gene family in the moss Ceratodon purpureus. Plant J. 13, 51–61 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Takio S., Yamamoto I. & Satoh T. Characterization of cDNA of the liverwort phytochrome gene, and phytochrome involvement in the light-dependent and light-independent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase gene expression in Marchantia paleacea var. diptera. Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 576–582 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K. et al. A phytochrome from the fern Adiantum with features of the putative photoreceptor NPH1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15826–15830 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsugu N., Mittmann F., Wagner G., Hughes J. & Wada M. A chimeric photoreceptor gene, NEOCHROME, has arisen twice during plant evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 13705–13709 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.-W. et al. Horizontal transfer of an adaptive chimeric photoreceptor from bryophytes to ferns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6672–6677 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulijasz A. T. & Vierstra R. D. Phytochrome structure and photochemistry: recent advances toward a complete molecular picture. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 14, 498–506 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell N. C. et al. Eukaryotic algal phytochromes span the visible spectrum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3871–3876 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duanmu D. et al. Marine algae and land plants share conserved phytochrome signaling systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15827–15832 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickett N. J. et al. Phylotranscriptomic analysis of the origin and early diversification of land plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E4859–E4868 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo L.-Y., Li F.-W., Chiou W.-L. & Wang C.-N. First insights into fern matK phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 59, 556–566 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. J., Goffinet B., Wickett N. J., Boles S. B. & Shaw A. J. Moss diversity: A molecular phylogenetic analysis of genera. Phytotaxa 9, 175–195 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gontcharov A. A. & Melkonian M. Molecular phylogeny and revision of the genus Netrium (Zygnematophyceae, Streptophyta): Nucleotaenium gen. nov. J. Phycol. 46, 346–362 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. et al. Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 81C, 71–85 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki F., Okamoto N., Pombert J. F. & Keeling P. J. The evolutionary history of haptophytes and cryptophytes: phylogenomic evidence for separate origins. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 279, 2246–2254 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. R. & Katz L. A. Building a phylogenomic pipeline for the eukaryotic tree of life – addressing deep phylogenies with genome-scale data. PLoS Curr. 6, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin B. Nested in the Chlorellales or independent class? Phylogeny and classification of the Pedinophyceae (Viridiplantae) revealed by molecular phylogenetic analyses of complete nuclear and plastid-encoded rRNA operons. Protist 163, 778–805 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal J. C. & Renner S. S. Hornwort pyrenoids, carbon-concentrating structures, evolved and were lost at least five times during the last 100 million years. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18873–18878 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest L. L. et al. Unraveling the evolutionary history of the liverworts (Marchantiophyta): multiple taxa, genomes and analyses. Bryologist 109, 303–334 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Adl S. M. et al. The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52, 399–451 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaroque N. et al. The complete DNA sequence of the Ectocarpus siliculosus Virus EsV-1 genome. Virology 287, 112–132 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H. S., Muller K. M., Sheath R. G., Ott F. D. & Bhattacharya D. Defining the major lineages of red algae (Rhodophyta). J. Phycol. 42, 482–492 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Keeling P. J. Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts. Am. J. Bot 91, 1481–1493 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. & Graham S. W. Inferring the higher-order phylogeny of mosses (Bryophyta) and relatives using a large, multigene plastid data set. Am. J. Bot 98, 839–849 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann F., Dienstbach S., Weisert A. & Forreiter C. Analysis of the phytochrome gene family in Ceratodon purpureus by gene targeting reveals the primary phytochrome responsible for photo- and polarotropism. Planta 230, 27–37 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikström N. Evolution of Lycopodiaceae (Lycopsida): estimating divergence times from rbcL gene sequences by use of nonparametric rate smoothing. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 19, 177–186 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis D. M. Taxonomic sampling, phylogenetic accuracy, and investigator bias. Syst. Biol. 47, 3–8 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer B. et al. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 161, 105–121 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Karniol B., Wagner J. R., Walker J. M. & Vierstra R. D. Phylogenetic analysis of the phytochrome superfamily reveals distinct microbial subfamilies of photoreceptors. Biochem. J. 392, 103–116 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman M., Coursin T., Rippka R., Houmard J. & de Marsac N. T. A new appraisal of the prokaryotic origin of eukaryotic phytochromes. J. Mol. Evol. 51, 205–213 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thümmler F., Dufner M., Kreisl P. & Dittrich P. Molecular cloning of a novel phytochrome gene of the moss Ceratodon purpureus which encodes a putative light-regulated protein kinase. Plant Mol. Biol. 20, 1003–1017 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanegae T., Hayashida E., Kuramoto C. & Wada M. A single chromoprotein with triple chromophores acts as both a phytochrome and a phototropin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17997–18001 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai H. et al. Responses of ferns to red light are mediated by an unconventional photoreceptor. Nature 421, 287–290 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H. et al. Ferns diversified in the shadow of angiosperms. Nature 428, 553–557 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettpelz E. & Pryer K. M. Evidence for a Cenozoic radiation of ferns in an angiosperm-dominated canopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11200–11205 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke T. J., Hickok L. G., Van der Woude W. J., Banks J. A. & Scott R. J. Photobiological characterization of a spore germination mutant dkgl with reversed photoregulation in the fern Ceratopteris richardii. Photochem. Photobiol. 57, 1032–1041 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Possart A. & Hiltbrunner A. An evolutionarily conserved signaling mechanism mediates far-red light responses in land plants. Plant Cell 25, 102–114 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S. Phytochrome-mediated development in land plants: red light sensing evolves to meet the challenges of changing light environments. Mol. Ecol. 15, 3483–3503 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S. & Tremonte D. Tests of the link between functional innovation and positive selection at phytochrome A: the phylogenetic distribution of far-red high-irradiance responses in seedling development. Int. J. Plant Sci. 173, 662–672 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yanovsky M. J., Casal J. J. & Whitelam G. C. Phytochrome A, phytochrome B and Hy4 are involved in hypocotyl growth responses to natural radiation in Arabidopsis: weak de-etiolation of the phyA mutant under dense canopies. Plant Cell Environ. 18, 788–794 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Sineshchekov V., Koppel L., Okamoto H. & Wada M. Fern Adiantum capillus-veneris phytochrome 1 comprises two native photochemical types similar to seed plant phytochrome A. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 130C, 20–29 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possart A., Fleck C. & Hiltbrunner A. Shedding (far-red) light on phytochrome mechanisms and responses in land plants. Plant Sci. 217–218, 36–46 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A. et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D225–D229 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R. & Posada D. ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 27, 1164–1165 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl D. J. Genetic Algorithm Approaches for the Phylogenetic Analysis of Large Biological Sequence Datasets Under the Maximum Likelihood Criterion. PhD thesis, Univ. Texas (2006). [The University of Texas at Austin] .

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R., Calcott B., Ho S. Y. W. & Guindon S. Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1695–1701 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. & Drummond A. J. Tracer v1.6. Available at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/ (2013).

- Gil M., Zanetti M. S., Zoller S. & Anisimova M. CodonPhyML: fast maximum likelihood phylogeny estimation under codon substitution models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1270–1280 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church S. H., Ryan J. F. & Dunn C. W. Automation and evaluation of the SOWH test of phylogenetic topologies with SOWHAT. bioRxiv doi:10.1101/005264 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Hofreiter M., Straube N., Corrigan S. & Naylor G. J. P. Capturing protein-coding genes across highly divergent species. BioTechniques 54, 321–326 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo V. Scythe - A Bayesian adapter trimmer (version 0.994 BETA). Available at https://github.com/vsbuffalo/scythe (2014).

- Joshi N. A. & Fass J. N. Sickle: a sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files (Version 1.33). Available at https://github.com/najoshi/sickle (2011).

- Luo R. et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience 1, 18 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-2, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data present in this publication can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5rs50.