Abstract

Patient: Male, 56

Final Diagnosis: Pancreatic GIST

Symptoms: Abdominal pain

Medication: None

Clinical Procedure: Whipple procedure

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors in the gastrointestinal system. These types of tumors originate from any part of the tract as well as from the intestine, colon, omentum, mesentery or retroperitoneum. GIST is a rare tumor compared to other types of tumors, accounting for less than 1% of all gastrointestinal tumors.

Case Report:

A 56-year-old male patient was hospitalized due to an upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and the start of abdominal pain on the same day. In the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that was performed, a solitary mass was found in the second section of the duodenum and a blood vessel (Forrest type 2a) was seen. The extent and location of the mass was detected by abdominal tomography. After hemodynamic recovery, a Whipple procedure was performed without any complications. A subsequent histopathological examination detected a c-kit-positive (CD117) pancreatic GIST with high mitotic index.

Conclusions:

The most effective treatment method for GISTs is surgical resection. In patients with a head of pancreatic GIST, the Whipple procedure can be used more safely and effectively.

MeSH Keywords: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors, Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Receptor Protein-Tyrosine Kinases

Background

GIST is a rare mesenchymal tumor in the gastrointestinal tract [1]. In Switzerland and Iceland, the annual incidence rates are 14.5/1 000 000 and 3/1 000 000, respectively, and in the USA, there are about 4000 new cases every year [2–4]. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGISTs) originate from outside of the gastrointestinal tract and are usually seen in the omentum, mesentery, retroperitoneal, or other intra-abdominal localizations [3,4]. The incidence rate of EGIST is 7–10/1 000 000 [2,7]. Pancreatic GISTs, with an annual incidence rate of 3/1 000 000, are part of the same family as EGISTs but have been less reported on in the literature [3,5]. While the etiopathogenesis of EGISTs is not clearly defined, it is believed to arise from the progenitor of Cajal cells, which are responsible for providing communication between the muscular layer and myenteric layers after mutations of the tyrosine kinase receptors, such as c-kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptor oncogene alpha (PDGFRA) [6,7]. In patients with EGISTs, medical and surgical adjuvant therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib (imatinib mesylate, Glivec™, STI-571) has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrence and increase survival after 1 year of therapy [7,9].

The following report presents a case of pancreatic GIST that received follow-up care and treatment after upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and the performance of a Whipple procedure at our clinic.

Case Report

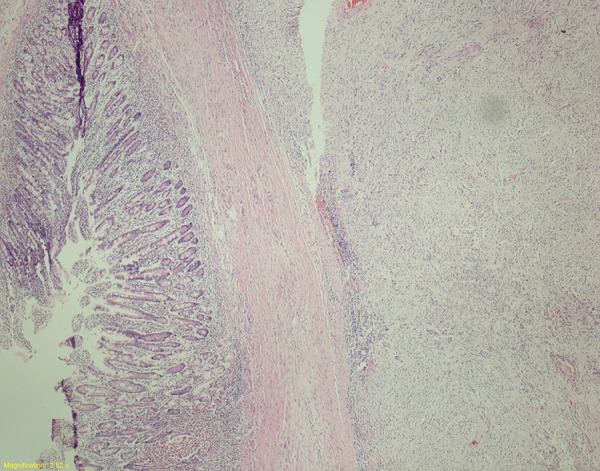

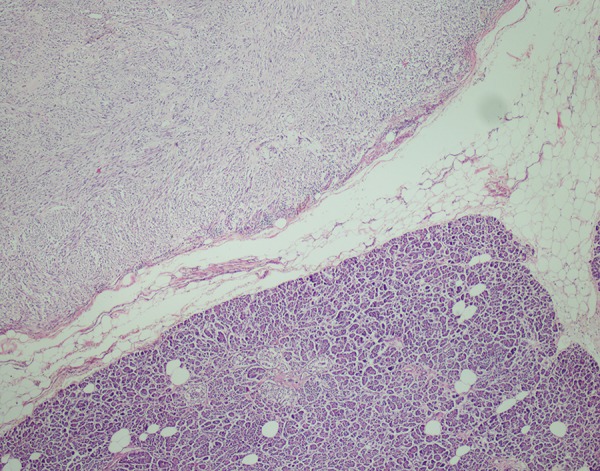

A 56-year-old male patient was hospitalized due to an upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and abdominal pain. The patient’s history revealed that the hemorrhage had started on the same day as one of his episodes of abdominal pain, which had been ongoing for 3 months. His body mass index (BMI) was 20 kg/m2, and over a period of 6 months he had lost 10 kg body weight. The patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were 7.2 mg/dl and 22.8%, respectively. He was taken to the intensive care unit, where he was monitored and administered oxygen and intravenous fluids. The patient was then given 2 units of erythrocyte suspension and 1 unit of fresh frozen plasma, and an upper endoscopy was planned. In the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that was performed, a solid mass was detected in the second section of the duodenum and a blood vessel (Forrest type 2a) was seen. Hemostasis was performed using hemoclips and the injection of adrenaline. A solitary mass, 4 cm in diameter, was observed in the second section of the duodenum in the abdominal ultrasonography (USG) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (Figures 1, 2). A control upper GIS endoscopy was conducted and numerous biopsies were taken from the mass. However, the results of the biopsies were inadequate. Following an anesthesia consultation, it was determined that his physical status was ASA-3 (American Society of Anesthesiologists). The patient’s tumor markers were normal and an abdominal operation was planned. A midline laparotomy was performed and after opening the abdominal cavity and conducting an exploration, a tumoral mass, approximately 4 cm in diameter and consisting of the head of the pancreas and uncinate process, was found. After no invasion of adjacent tissue or metastases was seen, a Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) was performed without any complications (Figure 3). A subsequent histopathological examination showed a c-kit-positive (CD117) GIST with a high mitotic index and pancreas origin. The tumor was not seen in the surgical margins (Figures 3–7). The patient was discharged in good condition on the sixteenth day following the procedure. His general condition continues to be good and he receives regular follow-up care at the Oncology Department, where he is administered imatinib treatment.

Figure 1.

Pancreatic GIST with ultrasonography.

Figure 2.

Pancreatic GIST in computed tomography in relation with duodenum and vasculars (arrow).

Figure 3.

Whipple procedure specimen and pancreatic GIST (arrow).

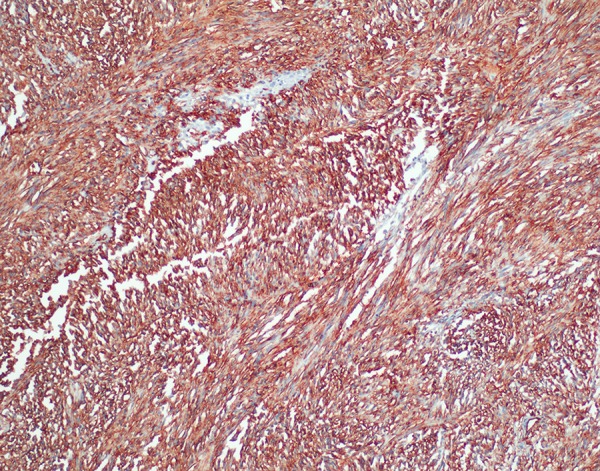

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry CD34 positivity (×200) (H&E).

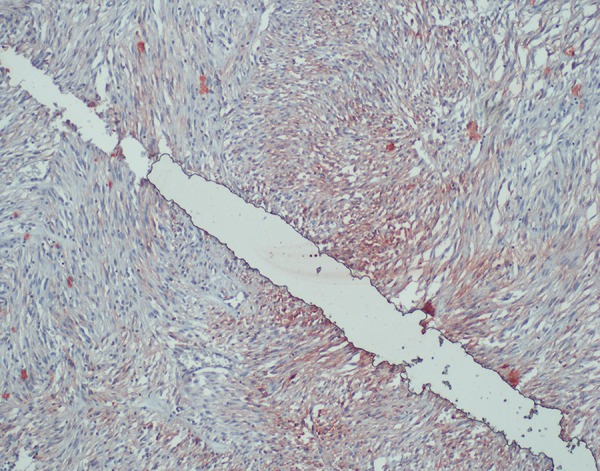

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry CD117 positivity (×200) (H&E).

Figure 6.

Relation between duodenum and tumor(×40) (H&E).

Figure 7.

Relation between pancreas and tumor(×40) (H&E).

Discussion

GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract malignities [1,2]. The tumors were originally defined by Golden and Stout in 1941 as bona fide smooth muscle tumors or precursors of leiomyoma [3]. After the discovery of electron microscopy and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, Mazur and Clark were the first to use the term “stromal tumor” in 1983 [4].

GISTs represent less than 1% of all gastrointestinal tumors [5]. The most common locations of these tumors are the stomach (50–70%), small bowel (20–30%) and colon/rectum (10%) [5]. EGISTs are frequently located in the omentum, mesentery or retroperitoneum. Cases of pancreatic GIST are extremely rare [5,6]. Agaimi et al. [6] reported a 1.5% rate of EGISTs in all of GISTs. These tumors are most often seen in the middle to later stages of life, where the 60–80 year old age group constitute the highest proportion of cases and 75% of cases are over 50 years old (median age: 58) [3,4,6]. The etiopathogenesis of GISTs has not been definitively described. Based on the immunophenotypic characterization and the similarity of ultrastructural and cell signaling in GIST pathogenesis, it is believed that the c-kit positive cells of the ICC (Interstitial Cells of Cajal) progenitor are generated by somatic mutations of PDFRα or KIT (CD117, c-kit) [7]. Most GIST cases are isolated incidences; however, in families with c-KIT and platelet-derived growth factor-α (PDGFR-α) mutations and neurofibromatosis Type 1, the incidence of EGIST increases [7]. In immunohistochemical studies, CD117-positive cells have been found in the omentum and mesothelial [8]. The immunohistochemical staining done in our case showed that tumor cells were stained with CD117 (c-KIT), CD34 and actin (Figures 4–6).

GISTs include a wide array of symptoms, which may vary according to location in the GI tract, tumor size and localization of the organ wall. Patients may even be asymptomatic, depending on tumor size and location [3,7]. Benign tumors are usually asymptomatic due to their small size and are typically discovered incidentally during the performance of surgery for another reason. However, some benign tumors can cause symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain [7,8]. In addition to abdominal pain, symptomatic patients may also experience hemorrhaging, loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness and fatigue, dysphagia and other complications, such as ileus and perforation [1,4,5,8]. A study of 288 primary GIST patients conducted by Nilsson et al. found that 69% of the tumors were symptomatic, 21% of the cases were found incidentally during surgery and the remaining 10% of the cases were discovered during performance of an autopsy [9]. In our case, the patient had upper gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain.

The history of the patient and their symptoms, physical examinations, endoscopic interventions and imaging techniques are important in the diagnosis of EGISTs. Although endoscopy interventions are useful in cases associated with gastrointestinal lumen, GIST is difficult to diagnose in endoscopic biopsies and is often misdiagnosed as mesenchymal tumors [5,10]. When a deep mucosal biopsy is taken on a neoplasm, the mucosal infiltration may be given specific histological diagnosis. In our case, an upper GI endoscopy showed a solid tumoral mass in the second section of the duodenum and a blood vessel (Forrest type 2a) was seen. An endoscopic ultrasonography can be used to determine how widely the disease has spread in patients without mucosa, and an endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) can be useful for diagnosis. The sensitivity of an endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of malignant GIST varies between 80–100% [10]. Additionally, positron emission tomography (PET), computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful for determining the extent of disease and the metabolic activity of the tumor [3,5,7,10) (Figure 2).

The prognoses of GISTs vary widely according to tumor size, mitotic index, organs from which the tumor originates, and c-KIT mutation. Fletcher et al. [11] showed that tumors have a stronger chance of being malignant in cases where they are more than 5 cm in size or in tumors that are less than 5 cm but have a number of mitosis on the 5 mitosis /50 (>5–10 mitoses per 50 high power fields) [12]. A study of 48 cases conducted by Reith et al. [2] reported that EGIST might show aggressive prognosis and metastases. The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) published a consensus based on tumor location and morphological characteristics, which can be referenced for diagnosis and prognosis purposes [8,11,12].

Surgical resection is the primary treatment used to address EGISTs [5,13]. However, the surgical resection of a pancreatic GIST can lead to various major complications, including massive hemorrhaging and pancreatic fistulas, due to the network of main vascular vessels and major organs. In cases where the GIST resection specimens have negative surgical margins, the prognosis of the disease is positive [13,14]. EGISTs tend to not involve the lymphatic system; therefore, systemic lymphatic dissection may not be included in standard surgical resection [14]. Depending on their location, gastrectomy, segmental bowel resection, hemicolectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure), and simple excision with negative margins may be performed [13–15]. Although the Whipple procedure has high morbidity and mortality, it can be used as a curative treatment option [15]. In our case, we planned to perform a curative surgery using the Whipple procedure (Figure 3).

Incomplete resection of the primary tumor is clearly associated with a much higher risk of recurrence. Čečka and Dematteo reported in their studies that neo/adjuvant chemotherapy could lead to reduced rates of local recurrence in high-grade EGISTs [16,17]. Imatinib is a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor used in the treatment of multiple cancers, most notably GISTs and Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) [9,18]. Imatinib can be safely used for treatment of recurrent or metastatic GIST after surgery or unresectable tumors [19]. The effectiveness of imatinib and the control process of the disease may be correlated with the type of mutation or the localization of KIT mutations [20]. In tumors with exon 11 mutations, 80% of them respond well to imatinib treatment and tumors with point mutations in exon 14 also respond to imatinib treatment [21]. However, only 50% of tumors with exon 9 respond to imatinib treatment and only partial responses have been seen in 20% of the mutation-free tumors [22]. In our patient, imatinib treatment was planned to be administered by the Oncology Department.

Conclusions

Pancreatic EGISTs are rare tumors that may be aggressive. The curative treatment method used for these tumors is surgical resection. The Whipple procedure can be safely performed in the curative surgical treatment of pancreatic GIST despite high mortality and morbidity.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

In our study, no financial support or sponsorship was received from any person or organization.

References:

- 1.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): definition, occurrence, pathology, differential diagnosis and molecular genetics. Pol J Pathol. 2003;54(1):3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reith JD, Goldblum JR, Lyles RH, Weiss SW. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumours: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Modern Pathology. 2000;13:577–85. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin BP. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: an update [review] Histopathology. 2006;48(1):83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenson JK. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and other mesenchymal lesions of the gut. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(4):366–75. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000062860.60390.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roggin KK, Posner MC. Modern treatment of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6720–28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agaimy A, Pelz AF, Wieacker P, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the vermiform appendix: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of 2 cases with literature review. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(8):1252–57. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta P, Tewari M, Shukla HS. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Surg Oncol. 2008;17:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(9):1109–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: The incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era, a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103(4):821–29. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji F, Wang ZW, Wang LJ, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors and diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;(8 Pt 2):318–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459–65. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda K, Hijioka M, Lee L, et al. A synchronous pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Intern Med. 2014;53(21):2483–88. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akbulut S, Yavuz R, Otan E, Hatipoglu S. Pancreatic extragastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report and comprehensive literature review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;6(9):175–82. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i9.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung JC, Chu CW, Cho GS, et al. Management and outcome of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(5):880–83. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeppner J, Kulemann B, Marjanovic G, et al. Limited resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Surgical management and clinical outcome. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5(2):16–21. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i2.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Čečka F, Jon B, Ferko A, et al. Long-term survival of a patient after resection of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising from the pancreas. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10(3):330–32. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1097–104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutkowski P, Przybył J, Zdzienicki M. Extended adjuvant therapy with imatinib in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recommendations for patient selection, risk assessment, and molecular response monitoring. Mol Diagn Ther. 2013;17(1):9–19. doi: 10.1007/s40291-013-0018-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold JS, van der Zwan SM, Gönen M, et al. Outcome of metastatic GIST in the era before tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:134–42. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9177-7. Erratum in: Ann Surg Oncol, 2007; 14: 3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vij M, Agrawal V, Pandey R. Malignant extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the pancreas. A case report and review of literature. JOP. 2011;9:200–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Debiec-Rychter M, Cools J, Dumez H, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib mesylate in gastrointestinal stromal tumors and activity of the PKC412 inhibitor against imatinib-resistantmutants. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):270–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen LL, Trent JC, Wu EF, et al. A missense mutation in KIT kinase domain 1 correlates with imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):5913–19. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]