Abstract

Light-chain amyloidosis is a relatively rare multisystem disorder. The disease often is normally difficult to diagnose due to its broad range of characters without specific symptoms. A 62-year-old male patient presented with heart failure after experiencing a long period of unexplained and untreated gastrointestinal symptoms. Clinical examination and laboratory findings indicated a systemic process with cardiac involvement. Echocardiography revealed concentric left ventricular hypertrophy with enhanced echogenicity and preserved ejection fraction. Rectum biopsy confirmed amyloid deposition. The side effect of delayed diagnosis on prognosis and the appropriate diagnostic strategy has been discussed.

Keywords: light-chain amyloidosis, cardiac amyloidosis, echocardiography, autonomic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy

Introduction

Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis is a disorder characterized by deposition of insoluble, monoclonal immunoglobulin light-chain fragments in various tissues. Clinical features depend on organs involved but can include restrictive cardiomyopathy, nephrotic syndrome, hepatic failure, and peripheral/autonomic neuropathy. The patients often have a long period of a certain organ involved before systemic multiorgan involvement or heart failure has already developed. Cardiac involvement is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in AL amyloidosis.1 Once congestive heart failure occurs in AL amyloidosis, median survival is less than 6 months if left untreated. Thus, an early and accurate diagnosis with an earlier start or more intensive treatment may have resulted in a better outcome.

Case report

A 62-year-old male presented with a 15-day history of dyspnea on exertion, associated with both lower extremity edema. Before this admission, he also had suffered from abdominal bloating and tasteless for a year with noticeable body weight loss at the same time (up to 20 kg). Over the past 6 months, he developed a multiple system disorder, which included painless paresthesias in the lower limbs, erectile dysfunction, and chronic diarrhea. He had an average stool frequency of up to ten times per day, with no obvious blood or mucus and no abdominal pain or tenesmus. Unfortunately, previous stomach and rectum biopsy did not examine for accumulations of amyloid fibril protein. His family history was unremarkable.

On physical examination, his blood pressure was 82/56 mmHg and heart rate was 52 bpm. Significant jugular venous distention, moderate hepatomegaly, and lower extremity edema were noted. A neurological examination revealed weakness and muscular atrophy in the bilateral tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius. Hyporeflexia was noted on both knees and ankles. Sensory examination revealed diminished tactile and pain sensation in a stocking and glove pattern and vibratory sensation was distally reduced in the lower limbs. The motor and sensory functions of upper extremities were relatively spared.

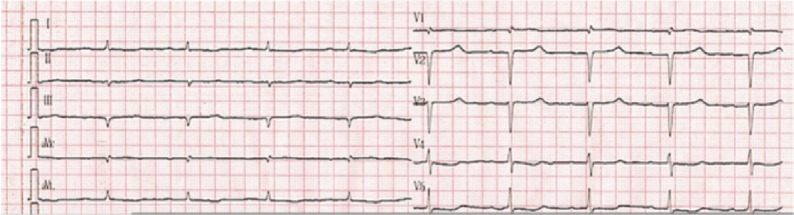

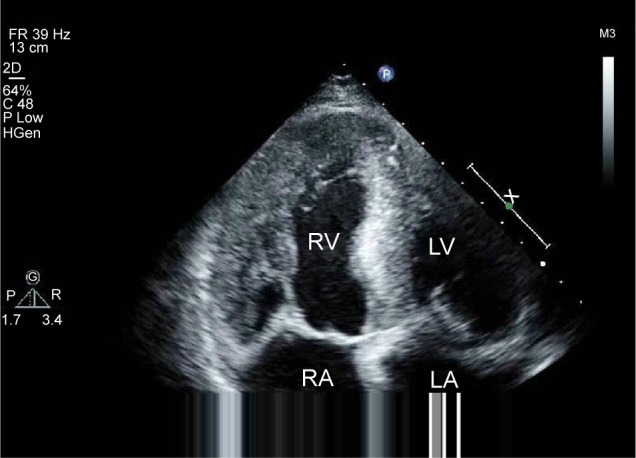

Initial laboratory data that included full blood count, transaminase, creatinine, electrolytes, cardiac troponin, and thyroid function were normal or negative. N-terminal fragment of pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 3,996 pg/mL. Nerve conduction studies confirmed bilateral sensory-motor neuropathy (Table 1). An electromyography study demonstrated active denervation and chronic reinnervation changes in the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius. Electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus rhythm, low voltages in limb leads, QS waves in precordial and inferior leads, first-degree atrioventricular block, and prolonged QTc (Figure 1). Two-dimensional echocardiography revealed marked concentrically thickened and speckled appearance of ventricular walls, biatrial dilatation, and left ventricular ejection fraction of 70% (Figure 2). Doppler revealed a severe restrictive mitral filling pattern with E/A ratio 2.1. Coronary angiography findings were normal.

Table 1.

Electrophysiological features of the patient were comparable with typical length-dependent, predominantly axonal sensory-motor polyneuropathy

| Nerve | MNCV (m/s)

|

CMAP (mV)

|

TL (ms)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | R | L | R | L | R | |

| Peroneal | 35.7 | 36.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Tibial | 36.0 | 36.7 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 5.2 | 5.1 |

| Median | 49.2 | 49.4 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| Ulnar | 48.9 | 47.8 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| SNCV (m/s) | SNAP (μV) | H-reflex (ms) | ||||

| Median | 41 | 39.7 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 34.7 | 32.9 |

| Ulnar | 44.4 | 42.9 | 8.4 | 8.1 | ||

| Sural | 19.6 | 22.3 | 3.2 | 2.9 | ||

Notes: Normal conduction velocities: median motor nerve ≥50.5 m/s; ulnar nerve ≥51.1 m/s; and sural nerve ≥32.1 m/s. Normal amplitudes: median motor nerve ≥6.0 mV; ulnar nerve ≥8.0 mV; and sural nerve ≥6.0 μV.

Abbreviations: MNCV, motor nerve conduction velocity; CMAP, compound muscle action potential; TL, terminal latency; L, left; R, right; SNCV, sensory nerve conduction velocity; SNAP, sensory nerve action potential.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm, low voltages in limb leads, QS waves indicative of pseudoinfarction in precordial and inferior leads, first-degree atrioventricular block, and prolonged QTc.

Figure 2.

A four-chamber apical view echocardiogram showing biatrial dilatation, valve thickening, thick ventricular walls (left ventricular wall is 15 mm and interventricular septum is 19 mm), and interventricular septum with speckled appearance, which suggests amyloid infiltrate.

Abbreviations: RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium.

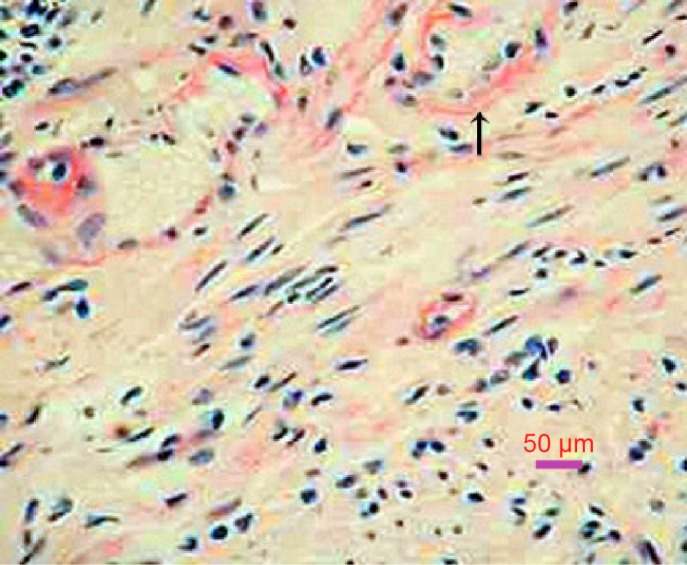

The combined occurrence of low QRS voltage in the ECG, ventricular thickening, and signs of diastolic dysfunction is strongly suggestive of cardiac amyloidosis. The following serum λ light-chain concentration was 1,763 (normal range: 598–1,329 mg/dL, and κ light-chain concentration was normal. Rectum biopsy confirmed amyloid infiltrate (Figure 3). So, the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis was established. Despite chemotherapy administration of melphalan, dexamethasone, immunomodulator lenalidomide, and supportive therapy including montmorillonite to decrease diarrhea and low-dose furosemide to alleviate fluid retention, the patient continued to deteriorate and died at home after 3 months after the initial diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Rectum biopsy: amyloid deposits are confirmed by a positive Congo red stain (arrow), which gives the characteristic salmon pink color (200×).

Discussion

Amyloidosis refers to a collection of conditions in which abnormal protein folding results in insoluble fibril deposition in tissues. The major types of amyloidosis, classified on the basis of their precursor protein, include light-chain, senile systemic (wild-type transthyretin), hereditary (mutant transthyretin), and secondary (AA) diseases. The frequency of cardiac involvement varies among the types of amyloidosis and is common with AL disease.2 Myocardial amyloid involvement leads to a restrictive cardiac physiology with possible concomitant conduction system disease, and the patients may present with nonspecific dyspnea, lower extremity edema, and syncope. Death in more than half of the patients with cardiac amyloidosis is due to heart failure or refractory arrhythmia.

Echocardiography should be the first noninvasive test performed to evaluate for cardiac amyloidosis. Echocardiographic findings include biatrial dilatation and increased left ventricular wall thickness with diastolic dysfunction. Ejection fraction is generally preserved. These findings are also prevalent in other cardiac conditions such as hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy. However, ECG of our patient revealed low voltages, which was not typical for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Increased myocardial echogenicity with a granular or sparkling appearance is the most characteristic feature, as seen in the case. But this feature has limited sensitivity in cardiac amyloidosis and may be more indicative of late-stage disease. Advanced echocardiographic techniques are beginning to reveal more about the underlying pathology and functional abnormalities. With the tissue Doppler imaging technique, measurement of myocardial tissue velocity allows detection of early diastolic wall motion abnormalities before development of heart failure. However, a limitation of tissue Doppler imaging lies in its inability to distinguish between actively contracting myocardium and adjacent tethered akinetic myocardial segments. This limitation can be overcome by strain and strain rate imaging, which derives from speckle tracking imaging and is better able to distinguish among segmental wall motion differences.3 It is particularly helpful and demonstrates a very typical pattern in cardiac amyloidosis, characterized by relative sparing of apical longitudinal contraction compared to basal contraction. This appearance is not typically seen in other cardiomyopathies such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic stenosis.

The use of a combination of echocardiographic and electrocardiographic features increases specificity. A low voltage on the ECG and increased septal and posterior left ventricle wall thickness on the echocardiogram are highly specific for cardiac amyloidosis in the setting of biopsy-proven systemic amyloidosis. Low QRS voltages (all limb leads <5 mm in height) with poor R-wave progression in the chest leads (pseudoinfarction pattern) occur in up to 50% of patients with cardiac AL amyloidosis, and this is the most common finding in affected individuals. Ischemic cardiomyopathy may also result in decreased voltages and infarction pattern on ECG but leads to dilated, eccentric ventricular hypertrophy with reduced ejection fraction. Other findings include first-degree atrioventricular block (21%), nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay (16%), second- or third-degree atrioventricular block (3%), atrial fibrillation/flutter (20%), and ventricular tachycardia (5%).

A histologic specimen for confirmation of amyloid deposits is mandatory for an accurate diagnosis. Amyloid deposits produce characteristic apple-green birefringence under polarized light when stained with Congo red. The gold standard for diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis is still myocardial biopsy, but it may be connected with severe complications (ventricular free wall perforation up to 0.4%, arrhythmia 0.5%–1.0%, and conduction disorders 0.2%–0.4%).4 According to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines, there is a Class II-a recommendation to perform endomyocardial biopsy in heart failure associated with unexplained restrictive cardiomyopathy. Theoretically, typical echocardiographic appearances with a positive biopsy for amyloid, commonly from an extracardiac site (such as rectum or abdominal fat), is sufficient to make a diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis.5 Our patient had gastrointestinal symptoms, and the autonomic neuropathy has been considered to explain the symptoms. Biopsy from rectum confirmed amyloid infiltrate on Congo red staining.

Cardiac involvement is often a sign of advanced AL amyloidosis. In our case, the initial clinical presentation was dominated by chronic neuropathy and the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis took 1 year after the first symptom. This delay is unfortunately common to AL amyloid neuropathy, and the median duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 29 months. It can be explained by the chronicity and non-specificity of symptoms.

Pathologically, amyloid neuropathy is characterized by the deposition of insoluble β-fibrillar proteins in the epineurium, perineurium, endoneurium, perineuronal tissues, and neural vasculature. There are two types of amyloid that commonly infiltrate the nerve system. The first is familial amyloid polyneuropathy (also known as hereditary amyloidosis).6 The second is AL amyloidosis. Peripheral neuropathy occurs in 17% of patients with AL amyloidosis, making it the most common type of acquired amyloid polyneuropathy. Sensory-motor axonal polyneuropathy and carpal tunnel syndrome are the most common types of neuropathy associated with AL amyloidosis. Symptoms typically begin with painful paresthesias in the feet signifying small fiber involvement. As the disease progresses, it can affect larger nerve fibers and patients may complain of numbness and motor weakness.7 Up to 65% of patients with peripheral neuropathy also have autonomic nervous system involvement. The clinical manifestations of autonomic disorders are nonspecific and symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, postural lightheadedness, and erectile dysfunction. Due to varying clinical symptoms, the diagnosis of amyloid neuropathy is often a challenge. However, it is important to recognize and distinguish neuropathy from diseases of the end organs themselves. Diagnostic testing can include electromyography/nerve conduction studies, autonomic function tests.8 In this case, early diagnosis is particularly crucial so that patients might undergo the appropriate testing to find cardiac involvement in early stage. The discovery of which might lead to life-saving interventions.

Conclusion

In summary, AL amyloidosis is clinically heterogeneous with multisystem involvement. Presenting features are often nonspecific and difficult to characterize. Often, the discovery of cardiac involvement is a sign of late-stage disease. Increasing medical alertness of the natural history of AL amyloidosis could reduce the time to achieve the diagnosis and therapeutic decisions, also improving the prognosis. It should be stressed that some symptoms, seemingly unrelated to each other, are actually early and specific red flags of the amyloid process. Therefore, panels of differential diagnoses are certainly very useful.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Sharma N, Howlett J. Current state of cardiac amyloidosis. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2013;28(2):242–248. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835dd165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selvanayagam JB, Hawkins PN, Paul B, Myerson SG, Neubauer S. Evaluation and management of the cardiac amyloidosis [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(13):1501] J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2101–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koyama J, Ikeda S, Ikeda U. Echocardiographic assessment of the cardiac amyloidoses. Circ J. 2015;79(4):721–734. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frustaci A, Pieroni M, Chimenti C. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the diagnosis of cardiomyopathies. Ital Heart J. 2002;3:348–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koike H, Tanaka F, Hashimoto R, et al. Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:152–158. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohty D, Damy T, Cosnay P, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis: updates in diagnosis and management. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;106(10):528–540. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajkumar SV, Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Prognosis of patients with primary systemic amyloidosis who present with dominant neuropathy. Am J Med. 1998;104(3):232–237. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koike H, Hashimoto R, Tomita M, et al. Diagnosis of sporadic transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a practical analysis. Amyloid. 2011;18(2):53–62. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.565524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]