Abstract

The current study used longitudinal data to examine the role of emotional awareness as a transdiagnostic risk factor for internalizing symptoms. Participants were 204 youth, ages 7 to 16, who completed assessments every three months for a year. Results from hierarchical mixed effects modeling indicated that low emotional awareness predicted both depressive and anxiety symptoms for up to one year follow-up. In addition, emotional awareness predicted which youth went on to experience subsequent increases in depressive and anxiety symptoms over the course of the year. Emotional awareness also mediated both the cross-sectional and the longitudinal associations between anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that emotional awareness may constitute a transdiagnostic risk factor for the development and/or maintenance of symptoms of depression and anxiety, which has important implications for youth treatment and prevention programs.

Keywords: transdiagnostic, emotional awareness, depression, anxiety

There is increasing recognition of the critical role of emotion regulation in the development and maintenance of psychopathology. While there are several existing approaches to the conceptualization and measurement of emotion regulation, Thompson (1994, p. 27-28) has defined emotion regulation as, “the extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one's goals.” Across this and other definitions, emotion regulation is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct consisting of many distinct facets, such as identification of emotional states, tolerance of emotional arousal, and employment of adaptive coping strategies (e.g., Saarni, 1999; Thompson & Calkins, 1996). Accordingly, it is critical to understand the different roles of distinct facets of emotion regulation in the development and maintenance of psychopathology.

One of the initial steps in the process of emotion regulation is emotional awareness, which refers to the ability to identify and label internal emotional experience (Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). Emotional awareness, which is often referred to in the literature as emotional clarity (Salovey, Stroud, Woolery, & Epel, 2002) or alexithymia (Sifneos, 1973), is distinct from emotional expression in that awareness does not necessarily involve an outward display, but rather an internal cognitive recognition of the emotion that is present (Croyle & Waltz, 2002). This awareness has been highlighted as an important prerequisite for the execution of other effective emotional regulatory processes (Barrett & Gross, 2001; Saarni, 1999).

Individuals differ in their ability to notice, attend to, and differentiate internal emotional cues, and these individual differences in emotional awareness have important implications for effective emotion regulation. The ability to effectively identify one's emotions may enable a person to develop and activate an appropriate repertoire of behavioral, cognitive and emotional regulatory responses for dealing with the experience, and is associated with the increased use of a range of regulatory strategies (Barrett, Gross, Christensen, & Benvenuto, 2001). In essence, in order to initiate effective emotion regulation strategies, one may first need to recognize the presence of a distinct aversive emotional state to be regulated. In addition, the ability to understand one's emotions may enable one to allocate fewer resources towards deciphering internal experiences, allowing one to direct more resources towards the formulation of adaptive responses (Gohm & Clore, 2002). Consistent with this understanding of emotional awareness, research has shown that children and adolescents with low awareness of their emotional experiences identify fewer constructive coping strategies and demonstrate a diminished ability to cope with negative emotions and interpersonal stress (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010).

Emotional awareness may play a particularly salient role in emotion regulation as children emerge into adolescence. The development of emotional awareness may require abstract and meta-cognitive abilities that develop during early adolescence, allowing youth an emerging capacity to observe and think about their own emotions (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997). Further, adolescence may not only be a period during which this capacity emerges, but also one in which it is particularly needed. Adolescents report higher rates and intensity of negative emotion than preadolescents, as well as more negative emotion and more extreme mood swings than adults (Larson, Csikzentmihalyi, & Graef, 1980; Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989). As stress and negative emotions increase, the demand for effective emotion regulation rises, and the benefits of awareness in facilitating adaptive regulation become increasingly salient (Barrett et al., 2001). When faced with the increased stressors of adolescence, youth who have difficulty identifying their emotions might therefore have more difficulty developing effective strategies for emotion regulation, leaving them particularly at risk for the development of psychopathology.

The Transdiagnostic Role of Deficits in Emotion Regulation

Adaptive emotion regulation has been implicated as an essential feature of strong mental health in youth (Gross & Munoz, 1995), and deficits in healthy emotion regulation skills have consistently been associated with a wide range of child and adolescent psychopathology (Cicchetti, Ackerman, & Izard, 1995; Keenan, 2000). To briefly summarize, deficits in the ability to effectively regulate emotions have been implicated in depression (e.g., Silk, Steinberg & Morris, 2003), anxiety disorders (e.g., Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000; Suveg & Zeman, 2004), eating disorders (e.g., Sim & Zeman, 2004, 2006), posttraumatic stress disorder (e.g., Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, 2002), aggression (e.g., Bohnert, Crnic, & Lim, 2003), ADHD (e.g., Walcott & Landau, 2004), and self-injurious/suicidal behavior (e.g., Nock, Wedig, Holmberg & Hooley, 2008; Selby, Yen, & Spirito, in press). Across these disorders, deficits in emotion regulation have been found to contribute to the development, maintenance, or exacerbation of symptoms.

Given the role of emotional regulation deficits in such a wide range of disorders, poor emotion regulation (broadly defined) may be conceptualized as a potential transdiagnostic mechanism of psychopathology (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004; Kring & Sloan, 2010; Moses & Barlow, 2006). Transdiagnostic factors are factors that not only occur across multiple disorders, but also contribute to the etiology and/or maintenance of a range of disorders (Egan, Wade, & Shafran, 2011). By focusing on these shared maintaining mechanisms, the transdiagnostic approach may help explain high rates of comorbidity among disorders and frequent instability of diagnosis (Harvey et al., 2004). Depression and anxiety disorders in particular are known to co-occur at high rates (Brown & Barlow, 2009) and a better understanding of common, transdiagnostic processes underlying these internalizing disorders may help inform the development of more effective and efficient treatments.

Evidence from a cross-sectional study of young adults (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010) and a meta-analysis of emotion regulation and psychopathology (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010) supports the transdiagnostic role of emotion regulation in anxiety, depression, disordered eating, and substance use. In addition, in a longitudinal study of adolescents, emotion regulation was indicated as a transdiagnostic factor, increasing risk for a wide range of psychopathology in adolescents (McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, Douglas, Mennin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011). Together, these studies provide initial support for the transdiagnostic role of emotion regulation. However, emotion regulation is a multidimensional process consisting of many different skills, and there is evidence to suggest that some aspects of emotion regulation may play a more central role in psychopathology than others (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010). As such, a more nuanced understanding of the transdiagnostic role of distinct processes of emotion regulation is needed to better inform the development of transdiagnostic treatments.

Low Emotional Awareness as a Transdiagnostic Factor

Emotional awareness is one process of emotion regulation that has been conceptualized as a potential transdiagnostic process (e.g., Kring, 2008). The ability to identify one's emotional experiences may be a necessary prerequisite for effective emotion regulation, and deficits in emotional awareness may therefore be associated with the development and aggravation of symptoms. Indeed, low emotional awareness has been distinctly implicated in a range of disorders, particularly internalizing symptoms (Zeman, Shipman & Suveg, 2002). For example, low emotional awareness has been associated with childhood anxiety disorders (Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000), acute depression (Berthoz et al., 2000), and disordered eating (Sim & Zeman, 2005, 2006). In addition, low emotional awareness has also been associated with youth externalizing disorders such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (Casey, 1996).

Although increasing evidence indicates an association between emotional awareness and youth psychopathology, most studies of emotional awareness have examined single diagnoses, and further work is needed to establish if low emotional awareness represents a global risk factor for multiple forms of internalizing symptoms in the same individuals. Furthermore, the majority of these studies have used cross-sectional methods, precluding analyses of temporal relationships. As a result, it remains unclear whether low emotional awareness is a risk factor for, or corollary of, internalizing symptoms. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish the prospective role of low emotional awareness on symptom development and maintenance, and rule out the possibility that the presence of low emotional awareness across internalizing disorders is just epiphenomenal, occurring as a result of internalizing symptoms (Mansell, Harvey, Watkins, & Shafran, 2009).

Only one study to date has attempted to evaluate the potential role of low emotional awareness as a global risk factor for internalizing symptoms. In this study, McLaughlin et al. (2011) examined a unitary latent factor of “emotion dysregulation,” which consisted of emotional awareness, emotional expression, and ruminative responses to distress. This latent “emotion dysregulation” factor predicted subsequent increases in symptoms of anxiety, aggressive behavior, and disordered eating, but not depression, among adolescents. This study provides initial support for the role of emotional awareness as one aspect of a more general emotion dysregulation factor. However, given that some aspects of emotion regulation may play a more central role in psychopathology than others (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010), research is needed to examine the unique contribution of emotional awareness.

The Current Study

The current study was designed to examine the role of low emotional awareness as a transdiagnostic risk factor in child and adolescent internalizing disorders. We extended previous work by examining the prospective role of one distinct facet of emotion regulation, emotional awareness, in the development of internalizing symptoms over time for 204 youth across a wide range of development (grades 3-9). In addition, we extended previous studies, which have examined emotion regulation using only two time points, by including multiple assessments of symptoms every 3 months for 12-months. This design enabled us to examine the predictive role of emotional awareness over time and the stability of its effects.

Our hypotheses were three-fold. First, we hypothesized that lower levels of baseline emotional awareness would uniquely predict higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms over the course of one year, after controlling for baseline depressive and anxiety symptoms. Second, we hypothesized that in addition to predicting internalizing symptom levels over the course of the year, low emotional awareness would also predict which children went on to experience subsequent increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety at any point over the course of the year, highlighting the role of low emotional awareness as a risk factor for increased internalizing symptoms.

Third, as McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema (2011) have noted, if a risk factor is indeed transdiagnostic, leading to both depression and anxiety, then the comorbidity between symptoms of depression and anxiety over time should be mediated by the transdiagnostic risk factor. We therefore hypothesized that emotional awareness would mediate the relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Given that children typically experience anxiety symptoms earlier than depressive symptoms (Chaplin, Gillham, & Seligman, 2009; Wittchen, Kessler, Pfister, & Lieb, 2000), we expected that baseline anxiety symptoms would be associated with subsequent elevations in depressive symptoms, and that this relationship would be mediated by baseline emotional awareness.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a larger longitudinal study of the development of depression in children and adolescents. The original sample consisted of 316 youth (143 boys and 173 girls) who ranged in age from 7 to 16. However, the Emotional Expression Scale for Children (EESC) measure, which was used to assess emotional awareness in the current study, was at the end of a take-home packet of measures, and was therefore not completed by all participants. As a result, this study includes data from the 204 youth that completed the EESC at baseline (86 boys and 118 girls). No significant differences were found between individuals who did and who did not complete the EESC on baseline symptoms of depression (t(202)= .10, p = .90) or anxiety (t(200)= 2.0, p = .27). The average age was 11.65 (SD= 2.41) years. In terms of race/ethnicity, 67.6 % of the sample (N= 138) was White, 13.2 % was African-American (N=27), 15.2% was Asian (N=31), .5% was American Indian (N=1), and 3.4% was multiracial (N=7), with 7.4% identifying as Hispanic/Latino (N= 15).

Procedure

Letters were mailed home to the parents of students at participating schools in the central New Jersey area. Letters described the study and requested that interested families call the laboratory if interested in participating. Out of the 407 mother-child pairs who initially responded to these letters, 316 attended and completed the baseline assessment. Mothers and youth signed consent and assent forms. They completed a questionnaire battery, including assessments of depressive and anxious symptoms. Following this initial in-lab assessment, participants received a take-home packet of additional questionnaires, including the EESC as a measure of emotional awareness. After this baseline assessment, participants were contacted by phone every 3 months over a period of 12 months and completed questionnaires about depressive and anxious symptoms. Emotional awareness was assessed only at baseline and not follow-up assessments. Participants were compensated $10 for every hour of assessment they completed.

Regarding compliance to the study, 72.5% of the 204 participants in this study completed all 4 follow-up sessions, 91.1% completed 3 of the follow-up sessions, 96% completed 2 of the follow-ups, and 98.9% completed at least one follow-up session. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rutgers University.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Emotional Expression Scale for Children (EESC; Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002)

The EESC is a 16-item measure comprised of two 8-item subscales: a) emotional awareness and understanding and b) emotional expression. Children were asked to rate statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not at all true (1) to extremely true (5). The 8 items from each subscale were summed to generate a total subscale score ranging from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating less emotional awareness and greater expressive reluctance. A representative item from this subscale of the measure is, “I have feelings that I can't figure out.” The EESC has been shown to have high internal consistency and moderate test retest reliability, and construct validity has previously been established (Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). In this study we obtained good reliability, with a coefficient alpha of .90.

Repeated Measures

Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 2003)

The CDI is a 27-item widely used self-report questionnaire that assesses cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms of depression. Each item on the CDI consists of three statements, which vary in the severity of a given symptom. For each item, participants are asked to select the statement which best describes how they were feeling during the past week. Items are scored from 0 to 2 with a higher score indicating greater symptom severity. Total scores for this measure range from 0 to 54. The CDI has been shown to possess a high level of internal consistency and to distinguish children with major depressive disorders from non-depressed children (Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, 1984). In this study we obtained coefficient alphas that ranged between .82 and .85 over the 5 time points, indicating good reliability. The CDI was administered at baseline and every 3 months over the following year.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997)

The MASC is a widely used 39-item self-report measure of anxious symptoms designed for youth aged 8–19. Children are asked to indicate how often each item has been true for them in the last week, on a 4-point Likert scale. Items are scored from 0 to 3, with a higher score indicating greater symptom severity. The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety. Total scores for this measure are calculated by summing all items, and range from 0 to 117. The MASC has demonstrated good reliability and validity (March et al., 1997). In this study we obtained coefficient alphas that ranged between .88 and .90 over the 5 time points, indicating good reliability. The MASC was administered at baseline, and every 3 months over the following year.

Data Analytic Strategy

To examine our first hypothesis, we used hierarchical mixed effects modeling to assess the predictive role of emotional awareness on symptoms of depression and anxiety at follow-ups 3, 6, 9, and 12 months later. The mixed model approach accounts for two levels of data: within-subject (Level 1), where outcomes vary within subjects as a function of a person-specific growth curve, and between-subjects (Level 2), where the person-specific change parameters vary as a function of the participant's level of baseline vulnerability or other between-subjects differences. The mixed effects model approach models the scores of individuals at each time point and the covariance between the repeated measures over the assessments, allowing for examination of variance in non-independent observations. Analyses were run using the AR1 covariance structure, which accounts for auto-regression of observations repeated over time. Variables were examined as fixed effects and all cases (N=204) were included in the analyses, which were conducted using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation method. The significance level for all tests was α = 0.05 (two sided). All analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0.

Two parallel models were constructed, in which dependent variables were within-subject levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. The primary predictors of these dependent variables were: Time (continuous; Level 1), and baseline emotional awareness (Level 2). For each hypothesis, following examination of main effects, participant age, gender, and baseline depressive and anxiety symptomatology were entered as covariates to examine how robust the effects were. In addition, we included the cross-level interaction between emotional awareness and Time as a Level 2 predictor in the model to determine whether the association between emotional awareness and psychopathology changed over time. The mixed effects model equations are displayed below to further delineate model specification. The same model structure was implemented to examine anxiety symptoms.

Level 1: (Depressionij) = β0j + β1j (Time)ij

Level 2: (Individual): β0j = γ00 + γ01(Emotional Awareness)j + γ02(Baseline depression)j + γ03 (Baseline Anxiety)j + γ04(age)j + γ05(gender) + u0j

β1j = γ10 + γ11(Emotional Awareness)j

Emotional awareness scores were rescaled as deviations from the overall sample mean (grand mean centering), as doing so improves stability in model estimation and interpretability (Blanton & Jaccard, 2006; Enders & Tofighi, 2007). In addition, we examined potential moderators of the effects of emotional awareness on depressive and anxiety symptoms including age, gender, and baseline depressive and anxiety symptoms respectively. For each potential moderator, a two-way interaction with baseline emotional awareness was entered into the model. To further examine the unique contribution of emotional awareness, we examined the effects of emotional awareness when emotional expression was also included in each model.

In order to examine whether our inferences were impacted by attrition, which is common in longitudinal follow-up studies, pattern-mixture models were implemented (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997). This approach was chosen instead of imputation methods because imputation has potential for biasing results (Gueorguieva & Krystal, 2004; Tasca & Gallop, 2009). Only one pattern was examined, in which participants were considered either completers or dropouts, as has been done in previous studies (e.g., Dimidjian et al., 2006; Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997). As described by Gallop and Tasca (2009), a binary factor was created, in which dropouts were coded as 0 and completers were coded as 1. To examine whether the effects of emotional awareness on symptoms was dependent on the missing data pattern, an interaction between each significant effect and the pattern factor was entered into the model. The interaction between emotional awareness and the binary pattern factor was nonsignificant in both the depression model (B = −.02, SE = .10, t(362) = −.23, p = .82) and the anxiety model (B = .80, SE = 1.36, t(389) = .58, p = .56), suggesting that observed effects were not influenced by the pattern of missing data.

To examine our second hypothesis, that low emotional awareness functions as a risk factor predicting subsequent increases in internalizing symptoms, a dichotomous variable was created for both depression and anxiety in which participants who experienced an increase in symptomatology (relative to their individual baseline scores) at any point during follow-up were coded as 1, and participants who did not experience change in symptoms or only experienced decreases in symptoms were coded as 0. Binary logistic regression was then used to examine the role of emotional awareness in predicting subsequent elevations in symptoms. Doing so also allowed for a simple method of obtaining odds ratios for the impact of awareness on symptom onset.

For our third hypothesis, we examined whether emotional awareness contributed to the co-occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms. To do this, we examined the role of emotional awareness as a mediator of both the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms. In the cross-sectional analysis, we examined: 1) the association between baseline anxiety and depression symptoms; 2) the association between baseline anxiety and emotional awareness; 3) the association between emotional awareness and baseline depression; and 4) the attenuation in the association between anxiety and depression after including emotional awareness in the model.

In the longitudinal analysis, because emotional awareness was only measured at baseline and we wanted to examine the most proximal influences of emotional awareness over time, we examined associations between baseline anxiety symptoms, baseline emotional awareness, and subsequent depressive symptoms at the next assessment (3-month follow-up). We therefore examined 1) the association between baseline anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms at 3 months follow-up, controlling for baseline depressive symptoms 2) the association between baseline anxiety symptoms and emotional awareness; 3) the association between emotional awareness and depressive symptoms at 3 months follow-up, controlling for baseline depressive symptoms; and 4) the attenuation in the association between baseline anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms at 3 months follow-up after accounting for baseline depression and emotional awareness.

Only participants who completed assessments at 3 months follow-up (N=189) were included in the longitudinal mediation analyses. The PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007) was used to test the mediational impact of emotional awareness on the association between symptoms of depression and anxiety. This program tests mediational effects without the problems inherent in other methods of testing for mediation (e.g., inflated rates of Type I error; see MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). PRODCLIN examines the product of the unstandardized path coefficients divided by the pooled standard error of the path coefficients and a confidence interval is generated. If the values between the upper and lower confidence limits include zero, this suggests the absence of a statistically significant mediation effect.

Results

Baseline Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

The EESC and CDI variables were positively skewed, so each was transformed using a square root transformation. Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the baseline variables. Low emotional awareness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms demonstrated small-moderate significant correlations in the anticipated directions. Contrary to what might have been expected, low emotional awareness was also positively associated with age, suggesting that older youth demonstrated greater deficits in emotional awareness.

Table 1.

Baseline means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EESC Low EA | - | ||||

| 2. CDI | .42** | - | |||

| 3. MASC | .30** | .25** | - | ||

| 4. Child Age | .18** | .18** | −.10** | - | |

| 5. Gender | .13** | .042 | .11** | −.007 | - |

| Mean (SD) | 16.56 (6.75) | 7.64 (6.20) | 42.69 (15.72) | 11.65 (2.41) | - |

Note. CDI -Children's Depression Inventory; MASC -Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; EESC-Emotion Expression Scale for Children; EA- Emotional Awareness; ALEQ-Acute Life Events Questionnaire

*p<0.05

p< 0.01.

Baseline Cross-Sectional Analysis

As predicted, regression analyses revealed that low emotional awareness was a significant predictor of both baseline depression (t(203) = 6.02, p < .001, β = .39) and baseline anxiety (t(201) = 4.72, p < .001, β = .32) after controlling for age and gender, replicating previous findings (e.g., Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000; Zeman, Shipman & Suveg, 2002).

Hypothesis 1: Longitudinal Association between Emotional Awareness and Internalizing Symptoms

Hierarchical mixed effects models were used to assess the predictive role of emotional awareness on symptoms of depression and anxiety at follow-ups 3, 6, 9, and 12 months later. The observations-within-individuals nesting structure was justified by significant ICCs for both depressive symptoms (ICC= .86) and anxiety symptoms (ICC= .88), indicating that 86% of the variance in depressive symptoms and 88% of the variance in anxiety symptoms was between persons, with the remainder being within-person variation.

Table 2 displays results from the hierarchical mixed effects models. Low emotional awareness significantly predicted higher levels of both depressive symptoms (B = .26, SE = .09, t(597) = 2.85, p = .004) and anxiety symptoms (B = 3.22, SE = 1.19, t(597) = 2.70, p = .007) throughout follow-up, even after controlling for key covariates. The two-way interaction between time and emotional awareness was not significant in either model, suggesting that the significant effects of emotional awareness at baseline remained stable over time.

Table 2.

Longitudinal Mixed Effects Models

| Depression | Anxiety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | B | SE | t | |

| Time | −.21 | .02 | −10.24*** | −1.20 | .27 | −4.37*** |

| Low EA | .26 | .09 | 2.85** | 3.22 | 1.19 | 2.70** |

| Age | .06 | .01 | 4.10*** | −.27 | .19 | −1.38 |

| Gender | .04 | .07 | .57 | −150 | .91 | −1.65 |

| Baseline Depression | .11 | .007 | 16.75*** | −.09 | .09 | −1.06 |

| Baseline Anxiety | .008 | .002 | 3.76*** | .65 | .03 | 22.50*** |

| Time*EA Interaction | −.04 | .03 | −1.36 | −.49 | .35 | −1.41 |

Note. Low EA= Low Emotional Awareness

p < 05

p < .01

p < .001

Examining the Unique Contribution of Emotional Awareness

When emotional expression was added into the model predicting depressive symptoms, emotional awareness still significantly predicted depressive symptoms (B = .16, SE = .06, t(317) = 2.58, p = .01), while emotional expression did not (B = −.01, SE = .06, t(317) = −.18, p = .86). Similarly, when emotional expression was added into the model predicting anxiety, emotional awareness significantly predicted anxiety symptoms (B = 2.92, SE = 1.29, t(325) = 2.26, p = .02), while emotional expression did not (B = .52, SE = .82, t(325) = .63, p = .53). Emotional expression was therefore removed from both models.

Moderation of Emotional Awareness

For each potential moderator, a two-way interaction with baseline emotional awareness was entered one-by-one into each model. In the model predicting depressive symptoms there was no significant interaction between emotional awareness and age (B = .02, SE = .02, t(316) = 1.10, p = .27), gender (B = −.02, SE = .09, t(317) = −.22 , p = .82), or baseline depressive symptoms (B = −.0005, SE = .007, t(332) = −.08, p = .94). In the model predicting anxiety, there similarly was no significant interaction between emotional awareness and age (B = .17, SE = .22, t(323) = .75, p = .46), gender (B = .11, SE = 1.17, t(324) = .10, p = .92), or baseline anxiety symptoms (B = .03, SE = .03, t(316) = .98, p = .33).

Hypothesis 2: Emotional Awareness and Risk for Internalizing Symptom Development

To further examine the role of emotional awareness as a risk factor for developing internalizing symptoms, we created a dichotomous variable indicating whether participants experienced an increase in respective depressive and anxiety symptoms at any point during follow-up, relative to baseline. Participants who experienced increases in symptoms of depression (N= 84) or anxiety (N=125) were coded as 1, and participants who did not experience increases in depression (N=118) or anxiety (N=75) were coded as 0. Binary logistic regression analyses (results shown in Tables 3 and 4) indicated that lower emotional awareness at baseline predicted subsequent increases in depression symptoms during follow-up (B= .69, SE= .22, Wald= 10.04, p < .01, OR= 2.00), beyond the contributions of covariates. Similarly, lower emotional awareness at baseline also predicted subsequent increases in anxiety symptoms during follow-up (B= .69, SE= .26, Wald= 7.38, p < .01, OR= 2.00), beyond the contributions of covariates. Thus, low emotional awareness was significantly associated with approximately twice the likelihood of experiencing an increase in symptoms of both depression and anxiety for each unit decrease of emotional awareness.

Table 3.

Binary Logistic Regression Model Predicting Subsequent Increases in Depressive Symptoms

| B | SE | Wald | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .12 | .07 | 3.0 | 1.12 (.99 - 1.28) |

| Gender | −.03 | .31 | .01 | .97 (.53 – 1.78) |

| Baseline CDI | −.142** | .04 | 16.80 | .87 (.81 - .93) |

| Low EA | .69** | .22 | 10.04 | 2.00 (1.30 – 3.08) |

Note. EA-Emotional Awareness, CDI-Children's Depression Inventory

*p<0.05

p< 0.01.

Table 4.

Binary Logistic Regression Model Predicting Subsequent Increases in Anxiety Symptoms

| B | SE | Wald | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.04 | .08 | .26 | .96 (.83 - 1.12) |

| Gender | −.22 | .36 | .37 | .81 (.40 – 1.62) |

| Baseline MASC | −.102** | .02 | 39.71 | .90 (.88 - .93) |

| Low Emotional Awareness | .69** | .26 | 7.38 | 2.00 (1.21 – 3.30) |

Note. MASC- Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children

*p<0.05

p< 0.01.

Hypothesis Three: Emotional Awareness as a Mediator of the Relationship between Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

We first examined emotional awareness as a mediator of the cross-sectional association between symptoms of depression and anxiety. At baseline, anxiety was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (β = .18, p = .01). Both anxiety (β = .30, p < .001) and depression (β = .42, p < .001) were significantly associated with emotional awareness. In the final mediation model, anxiety was no longer associated with depression after emotional awareness was added to the model (β = .06, p = .37). The unstandardized path coefficients and standard errors of the path coefficients for the association between baseline symptoms of anxiety and depression via emotional awareness were entered into PRODCLIN to yield lower and upper 95% confidence limits of .023 and .068. This suggests that emotional awareness significantly mediated the association between symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Next, we examined a longitudinal mediation model with baseline anxiety as the source variable and depression at 3 months as the outcome variable. Baseline anxiety symptoms significantly predicted depressive symptoms at 3 months follow-up, controlling for baseline depression (β = .15, p = .005), in line with our hypothesis. As reported above, baseline anxiety was associated with emotional awareness as well as depressive symptoms at 3-months after controlling for baseline depression, and emotional awareness was associated with depressive symptoms at 3 months after controlling for baseline depression (β = .26, p < .001). In the final mediation model, baseline anxiety was no longer a significant predictor of depressive symptoms at 3 months, after controlling for baseline depression and emotional awareness (β = .10, p = .06). Although the effects of anxiety were nonsignificant, they trended towards significance, suggesting that there may be additional mediators of the association between anxiety and future depressive symptoms. Results from PRODCLIN yielded lower and upper 95% confidence limits of .011 and .039, suggesting that emotional awareness significantly mediated the association between baseline anxiety symptoms and subsequent depressive symptoms at 3 months. Additional examination of this longitudinal mediation relationship at 12-month follow-up revealed that emotional awareness continued to mediate the indirect relationship between baseline anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms at 12-months follow-up, yielding lower and upper 95% PRODCLIN confidence limits of .001 and .027.

Discussion

Emotional awareness is consistently conceptualized as the first step in the process of regulating emotions (e.g., Lane & Schwartz, 1987; Saarni, 1999). However, few studies have examined the consequences of low emotional awareness on internalizing symptoms during development from childhood to adolescence using longitudinal methods. The current study used longitudinal data from children and adolescents to examine emotional awareness as a transdiagnostic risk factor in the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms over the course of one year. Using mixed effects models, we found that low emotional awareness predicted both depressive and anxiety symptoms from baseline for up to one year follow-up, and these effects were not moderated by child age, gender, or baseline symptomatology. Furthermore, emotional awareness predicted which youth went on to experience subsequent increases in depressive and anxiety symptoms over the course of the year. Finally, emotional awareness also mediated both the cross-sectional and the longitudinal associations between anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that emotional awareness may constitute a transdiagnostic risk factor in the development and/or maintenance of symptoms of depression and anxiety, which has important implications for youth treatment and prevention programs.

Our findings on emotional awareness are consistent with existing literature demonstrating cross-sectional associations between emotional awareness and a broad range of youth symptomatology (e.g., Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000; Zeman, Shipman & Suveg, 2002). This study also supports and extends McLaughlin and colleagues’ (2011) study, which provided the first longitudinal evidence that emotion regulation might function as a transdiagnostic factor in multiple forms of psychopathology. The McLaughlin et al. (2011) study examined the role of emotional awareness as part of a broader construct of emotion dysregulation (including emotional awareness, emotional expression, and rumination) and found that deficits in these areas predicted the subsequent development of anxiety, aggression, and eating pathology, but not depression. However, given evidence that some aspects of emotion regulation may play a more central role in psychopathology than others (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010), the current study extends these findings by examining the distinct predictive role of emotional awareness in subsequent symptoms of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Together, these studies support conceptualizations of emotion dysregulation, and emotional awareness more specifically, as a transdiagnostic factor in psychopathology (Kring & Sloan, 2010; Moses & Barlow, 2006).

Despite a general consistency with regards to the role of emotional awareness in the development of depressive symptoms, our findings differed from those of McLaughlin and colleagues (2011), which found that emotional awareness (as measured by the same subscale of the EESC used in this study) was not predictive of depressive symptoms. One explanation for this discrepancy may be that the current study included youth from a greater age range (grades 3-9), potentially capturing different stages in the process through which emotional awareness influences symptomatology. Additionally, although emotional awareness provides an individual with information about their emotional states, this information may not always be used adaptively. While some youth may respond to this information by activating adaptive coping responses, others may activate maladaptive strategies such as avoidance or rumination. In this way, emotional awareness may only serve a beneficial function for youth who possess a repertoire of effective coping strategies to activate. Further research should examine the conditions under which emotional awareness is predictive of depressive symptoms.

Contrary to our expectations, low emotional awareness was positively associated with age at baseline, with older children demonstrating less awareness than younger children. Developmental research suggests that emotional awareness requires abstract and meta-cognitive abilities that develop during adolescence (Gottman et al., 1997), and one would therefore expect skills in this area to increase, and not decrease, with age. However, as youth grow up they also experience increased stressors, such as academic and social demands, and it may become more challenging for older youth to recognize and understand their more complicated emotional reactions to these experiences. Older youth may also experience more subtle and nuanced emotions (e.g., a mix of excited and nervous before a school dance), which may be more difficult to differentiate. Future research is needed to examine whether there might be a period of time during which youths’ emotional experiences increase in complexity before their cognitive abilities to comprehend them develop. Our finding of an insignificant relationship between gender and baseline depression is consistent with research suggesting that gender differences in depression often do not emerge until ages 13-15 (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994).

Results from this study also suggest that awareness of one's emotions may serve a distinctly beneficial role, above and beyond allowing for their expression. When both subscales of the EESC measure were entered into the mixed effects models, the emotional awareness subscale continued to predict symptoms of anxiety and depression, while the emotional expression subscale did not. The absence of a significant effect of emotional expression (after controlling for emotional awareness) is surprising in light of research demonstrating negative consequences of emotional suppression, which refers to the inhibition of emotion-expressive behavior (e.g., Gross, 2002; Richards & Gross, 1999). However, this finding is also consistent with previous research demonstrating that the emotion awareness factor of the EESC measure had a stronger pattern of correlations with measures of internalizing symptoms than the emotional expression factor (Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002).

To examine the role of emotional awareness as a risk factor for subsequent symptoms of depression and anxiety, binary logistic regression was used as a simple method of obtaining odds ratios for the effect of emotional awareness. Results indicated that emotional awareness was associated with increased risk (OR= 2.0) for developing symptoms of both depression and anxiety. Together with results from the hierarchical mixed effects models, these findings suggest that emotional awareness may function as a shared risk factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms.

One advantage of the transdiagnostic approach is that it may help explain high rates of comorbidity by identifying shared etiologic and maintaining factors across disorders. We therefore examined whether emotional awareness contributed to the co-occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Consistent with previous approaches (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011), we examined whether emotional awareness mediated the association between symptoms of depression and anxiety. Our finding that emotional awareness mediated the cross-sectional association between depressive and anxiety symptom suggests that low emotional awareness may help explain concurrent symptoms of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, emotional awareness fully mediated the relationship between baseline anxiety symptoms and subsequent depressive symptoms, suggesting that low emotional awareness may also help explain the progression from anxiety to depressive symptoms. Although it is unclear whether these associations are a direct effect of low emotional awareness or of resulting deficits in the use of regulation strategies, these findings provide initial evidence for the transdiagnostic role of emotional awareness in the co-occurrence of internalizing symptoms.

Potential Mechanisms of Low Emotional Awareness

To date there has not been any research conclusively demonstrating the mechanism through which low emotional awareness contributes to psychopathology. It is often suggested that emotional awareness is protective from the development of psychopathology by providing an individual with information about their emotional states, which in turn allows them to activate emotion regulation strategies and respond adaptively (e.g., Saarni, 1999; Swinkels & Giuliano, 1995). Consistent with this theory, emotional awareness has been associated with increased use of regulatory strategies, with an individual's recognition of the presence of a discrete emotion enabling the activation of adaptive responses (Barrett et al., 2001; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2002). In contrast, children and adolescents with low awareness of their emotional experiences identify fewer constructive coping strategies and demonstrate a diminished ability to cope with negative emotions and interpersonal stress (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010; Sim & Zeman, 2005, 2006). Perhaps as a result, youth with lower emotional awareness may feel more overwhelmed by their emotional experiences, and report increased levels of negative affect (Ciarrochi, Heaven, & Supavadeeprasit, 2008). In this way, low emotional awareness may contribute to symptoms of both depression and anxiety by preventing youth from accessing information that enables them to recognize and cope with negative affect and arousal. This inability to cope with emotional responses to stressful events may lead to more severe periods of distress that evolve into depression or anxiety (e.g., Mennin, Holaway, Fresco, Moore, & Heimberg, 2007). However, this causal link has not been demonstrated empirically. It is also possible that knowing and labeling one's emotions may be beneficial by allowing for increased social support (Ciarrochi, Heaven, & Supavadeeprasit, 2008) or cognitive defusion (Hayes, Strosahl & Wilson, 1999), allowing a person to observe their emotions from some distance rather than feeling consumed by them. Future studies are needed to examine these potential mechanisms of emotional awareness.

Implications

Our findings have important implications for prevention and treatment interventions targeting youth anxiety and depression. As one of the first studies to demonstrate the role of low emotional awareness in predicting subsequent internalizing symptoms, this study provides initial support for the integration of emotional awareness training in both treatment and prevention programs for youth depression and anxiety. Emotional awareness training might include a focus on teaching youth to recognize and interpret interoceptive signs of their emotions, a rich vocabulary with which to label their emotions, and an understanding of the causes and consequences of their emotions. Such interventions might also encourage youth to monitor their daily emotions in order to increase their awareness. Many interventions already integrate components such as these, which are designed to increase emotional awareness. For example, treatments for adolescent depression and anxiety often begin by teaching adolescents to identify and monitor their feelings (e.g., Kendall & Hedtke, 2006; Lewinsohn & Clarke, 1984). These interventions provide a model for the potential integration of emotional awareness training into cognitive behavioral treatments for a range of disorders. The current study provides longitudinal data suggesting that other interventions may benefit from a similar integration.

Findings from this study also support the integration of emotional awareness training into transdiagnostic treatment and prevention programs. Our findings suggest that emotional awareness may constitute a transdiagnostic factor that is relevant in both depression and anxiety disorders. In light of growing recognition that the co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in youth may be a result of shared etiological factors (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004), the importance and potential benefit of transdiagnostic interventions for youth has become increasingly salient. By targeting cross-cutting mechanisms of psychopathology such as emotional awareness, transdiagnostic interventions may treat and prevent multiple forms of psychopathology, reducing the clinical burden associated with comorbid conditions (Harvey et al., 2004). Results from this study support the inclusion of emotional awareness as an important target for such transdiagnostic interventions.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the promising results from this study, findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, depression and anxiety were measured using self-report measures, and further research is needed to replicate these findings using multi-informant assessments and semi-structured interviews. However, the self-report measures used in this study have been well established and validated, improving the internal validity of our conclusions (e.g., Timbremont, Braet, & Dreessen, 2004; Baldwin & Dadds, 2007). Similarly, emotional awareness was also measured using a self-report measure, which is limited by the fact that youth with low emotional awareness may also have low self-awareness more generally, limiting their ability to accurately report on their internal experiences. However, the EESC is a widely used and validated measure that has been associated with other measures of emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms (Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). In future research it may be more effective to measure emotional awareness in real time through electronic devices that signal participants to label their current emotions; however, this methodology is costly and time-intensive and less feasible for a large longitudinal study with a community sample.

Second, this study assessed symptoms in youth from a community sample in which overall levels of depression and anxiety were somewhat lower than in clinical samples. Furthermore, symptom scores declined over time, as is often the case in longitudinal research involving community samples, potentially because of habituation to the questionnaire or regression to the mean (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). Although this study suggests the importance of emotional awareness in subclinical levels of symptomatology, replication with a clinical sample is necessary. Finally, because we only measured emotional awareness at baseline, we were unable to examine whether symptoms of depression and anxiety predicted subsequent impairments in emotional awareness. While our findings suggest that emotional awareness predicts subsequent increases in symptomatology, it is possible that there is a reciprocal relationship in which the presence of symptomatology also further impairs emotional awareness. However, in a previous study emotional awareness and other emotion regulation strategies predicted subsequent psychopathology, but not vice versa, suggesting that emotion regulation deficits are not caused by psychopathology (McLaughlin et al., 2011). Still, further longitudinal research is needed to examine this possibility.

Future research should continue to examine the mechanisms through which emotional awareness is associated with internalizing symptoms. More information is needed to better understand the adaptive benefits of emotional awareness and the link between deficits in this area and the development of psychopathology. In addition, this study only examined the role of emotional awareness in depression and anxiety, and future studies should examine its role in a wider range of both internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study provides longitudinal evidence demonstrating the role of emotional awareness as a transdiagnostic risk factor in depression and anxiety among children and adolescents. This study extends findings from cross-sectional studies of emotional awareness, demonstrating its predictive association with subsequent symptoms of depression and anxiety. In addition, emotional awareness mediated the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between symptoms of anxiety and depressive symptoms, suggesting it may help explain the high rates of co-occurrence of these disorders. With the development of transdiagnostic treatment and prevention programs there is increasing importance in identifying common factors that contribute to or maintain symptoms across a range of disorders. Our findings highlight the potential benefits of integrating emotional awareness training into both transdiagnostic and disorder-specific interventions.

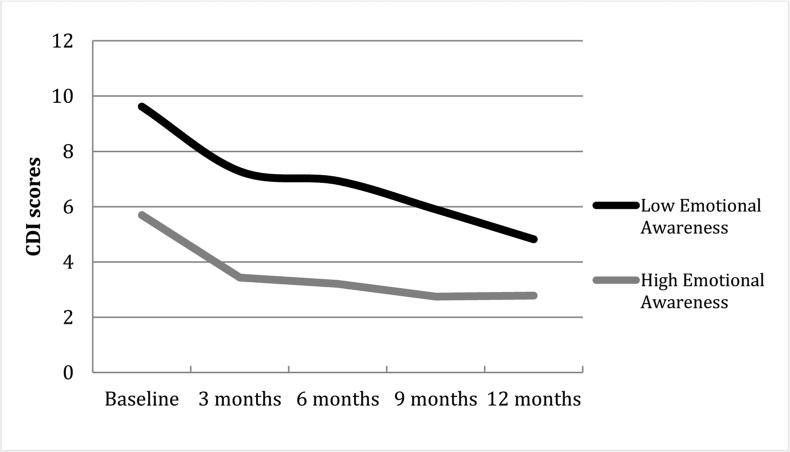

Figure 1.

Average Depressive Symptoms by Assessment

Note. A mean split was conducted to create high and low EA groups; CDI-Children's Depression Inventory.

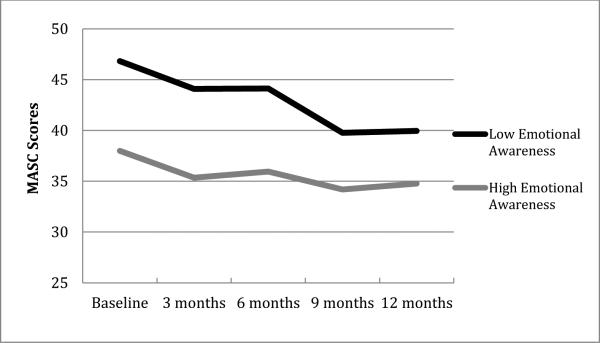

Figure 2.

Average Anxiety Symptoms by Assessment

Note. A mean split was conducted to create high and low EA groups; MASC- Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(10):974. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JS, Dadds MR. Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):252–260. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Gross JJ. Emotional intelligence: A process model of emotion representation and regulation. Guilford Press, New York, NY.; New York, NY, US: 2001. pp. 286–310. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Gross J, Christensen TC, Benvenuto M. Knowing what you're feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion. 2001;15(6):713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz S, Ouhayoun B, Parage N, Kirzenbaum M, Bourgey M, Allilaire J. Étude préliminaire des niveaux de conscience émotionnelle chez des patients déprimés et des contrôles. Annales Médico-Psychologiques. 2000;158(8):665–672. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H, Jaccard J. Arbitrary metrics in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006;61:27–41. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert AM, Crnic KA, Lim KG. Emotional competence and aggressive behavior in school-age children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:79–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1021725400321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification syste ased on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21(3):256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey RJ. Emotional competence in children with externalizing and internalizing disorders. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, NJ.; Hillsdale, NJ, England: 1996. pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Gillham JE, Seligman ME. Gender, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms A Longitudinal Study of Early Adolescents. The Journal of early adolescence. 2009;29(2):307–327. doi: 10.1177/0272431608320125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Heaven PCL, Supavadeeprasit S. The link between emotion identification skills and socio-emotional functioning in early adolescence: A 1-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(5):565–582. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, Han H. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(5):1067–1074. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle KL, Waltz J. Emotional awareness and couples’ relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2002;28:435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Ackerman BP, Izard CE. Emotions and emotion regulation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan SJ, Wade TD, Shafran R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(2):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD. The contribution of deficits in emotional clarity to stress responses and depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31(4):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallop R, Tasca GA. Multilevel modeling of longitudinal data for psychotherapy researchers: II. The complexities. Psychotherapy Research. 2009;19(4-5):438–452. doi: 10.1080/10503300902849475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16(4):495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(3):281–291. doi: 10.1017/s0048577201393198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Muñoz RF. Emotion regulation and mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1995;2:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: Progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Watkins ER, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press, New York, NY.; New York, NY, US: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K. Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7(4):418–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hedtke K. Coping Cat Workbook. Workbook Publishing; 2nd Ardmore, PA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory: Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM. Emotion disturbances as transdiagnostic processes in psychopathology. Handbook of emotion. 2008:691–705. [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Sloan DM, editors. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Schwartz GE. Levels of emotional awareness: A cognitive-developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144(2):133–143. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M, Graef R. Mood variability and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1980;9(6):469–490. doi: 10.1007/BF02089885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Lampman-Petraitis C. Daily emotional states as reported by children and adolescents. Child Development. 1989;60(5):1250–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN. Group treatment of depressed individuals: The “coping with depression” course. Advances in Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1984;6(2):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(3):384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods. 2002;7(1):83. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Harvey A, Watkins E, Shafran R. Conceptual foundations of the transdiagnostic approach to CBT. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23(1):6–19. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mennin DS, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(9):544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour research and therapy. 2011;49(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Holaway RM, Fresco DM, Moore MT, Heimberg RG. Delineating components of emotion and its dysregulation in anxiety and mood psychopathology. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38(3):284–302. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Wedig MM, Holmberg EB, Hooley JM. The emotion reactivity scale: Development, evaluation, and relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological bulletin. 1994;115(3):424. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penza-Clyve S, Zeman J. Initial validation of the emotion expression scale for children (EESC). Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(4):540–547. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Gross JJ. Composure at any cost? the cognitive consequences of emotion suppression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25(8):1033–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. The development of emotional competence. The Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Stroud LR, Woolery A, Epel ES. Perceived emotional intelligence, stress reactivity, and symptom reports: Further explorations using the trait meta-mood scale. Psychology and Health. 2002;17(5):611–627. [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Spirito A, Bennett B. The children’s depression inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:955–967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Yen S, Spirito A. Time varying prediction of suicidal ideation in adolescents: Weekly ratings over six month follow-up. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.736356. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifneos PE. The Prevalence of ‘Alexithymic’Characteristics in Psychosomatic Patients. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1973;22(2-6):255–262. doi: 10.1159/000286529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: links to depressive symptoms and problem behaviors. Child Development. 2003;74:1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Zeman J. Emotion awareness and identification skills in adolescent girls with bulimia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:760–771. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Zeman J. Emotion regulation factors as mediators between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms in early adolescent girls. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:478–496. [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Zeman J. The contribution of emotion regulation to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in early adolescent girls. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;35:219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC. A preliminary study of the emotion understanding of youth referred for treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:319–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall C. Emotion regulation and understanding: implications for child psychopathology and therapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:189–222. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C, Zeman J. Emotion regulation in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:750–759. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels A, Guiliano TA. The measurement and conceptualization of mood awareness: Monitoring and labeling one’s mood states. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:934–949. [Google Scholar]

- Tasca GA, Gallop R. Multilevel modeling of longitudinal data for psychotherapy researchers: I. The basics. Psychotherapy Research. 2009;19:429–437. doi: 10.1080/10503300802641444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Calkins SD. The double-edged sword: Emotional regulation for children at risk. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8(1):163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B, Braet C, Dreessen L. Assessing depression in youth: relation between the children’s depression inventory and a structured interview. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:149–157. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the children's depression inventory: a meta-analysis. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2002;111(4):578–588. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott C, Landau S. The relation between disinhibition and emotion regulation in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:772–782. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Pfister H, Höfler M, Lieb R. Why do people with anxiety disorders become depressed? A prospective-longitudinal community study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102(s406):14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Suveg C. Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(3):393–398. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]