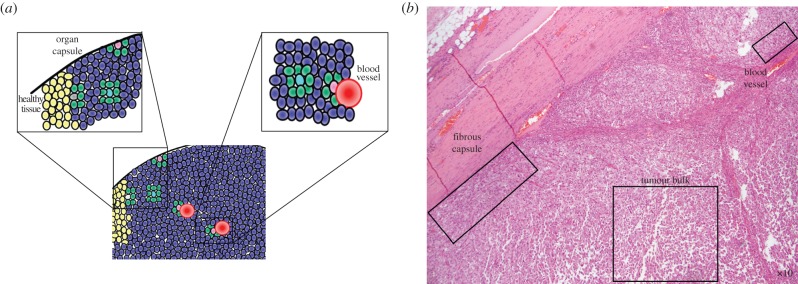

Figure 1.

An idealized image of a hypothetical tumour (a), and a clinically produced micrograph of a sarcoma under low power stained with haematoxylin and eosin (b). A tumour cell (a: blue cells) has several different scenarios that affect the architecture of its neighbourhood geometry which we illustrate here. On short time scales, cells in a solid tumour experience largely static neighbourhood architectures; however, cells in the bulk of the tumour (a: turquoise; b: lower right box) have many more neighbours than cells against static boundaries (pink) like an organ capsule (a: left close-up), fibrous capsule (b: left box) or blood vessel (a: right close-up; b: upper right box). This change in relative number of neighbours affects evolutionary game dynamics. The boundary between the tumour and healthy cells (yellow), while of interest, is a dynamic edge and is not considered in this article. (Online version in colour.)