Introduction

Papulonecrotic tuberculid is characterized by symmetric eruption of necrotizing papules on extensor aspect of extremities, sometimes healing with a varioliform scar formation. It is infrequently reported but is not uncommon in areas where tuberculosis is endemic. Tuberculin test is generally positive while pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis is often associated. Rapid response to antitubercular therapy leaves no doubt of tuberculous etiology even when no active focus of tuberculosis is present.

Case report

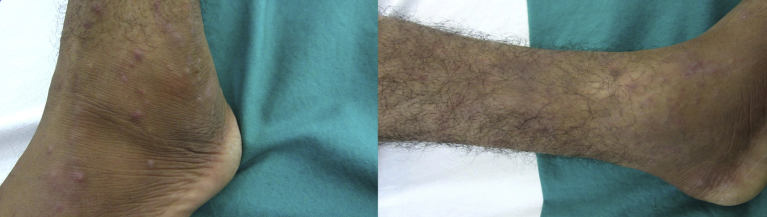

A 25 year old male patient presented with history of recurrent, multiple, pus-filled lesions over both legs of two months duration. He had been treated repeatedly as a case of recurrent boils with both oral and topical antibiotics. There was no history of itching, fever, drug intake prior to the onset of lesions, weight loss, chronic cough or abdominal pain. General and systemic examination was essentially normal. Dermatological examination revealed presence of multiple, pus-filled, necrotic erythematous papules involving both lower legs. Bilateral pitting pedal edema was present. Patient was started on oral and topical antibiotics (capsule amoxycillin with clavulanic acid and topical 2% mupirocin) along with non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and topical potassium permanganate soaks. Within the next few days the pus discharge and pedal edema regressed to a certain extent but further dermatological examination revealed presence of multiple violaceous nodular lesions over lower one-third of legs and both ankles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Multiple violaceous papulonodular lesions seen over both legs and feet.

Relevant haematogical and biochemical parameters were essentially normal. Mantoux test at 72 h was positive with a 20 mm induration. Doppler evaluation of the lower limb venous system to rule out other causes of pedal edema was normal. Chest radiograph and ultrasound abdomen revealed no abnormalities. Skin biopsy showed a normal epidermis. Superficial dermis showed moderate perivascular infiltrate. Deep dermis showed large, coalescing epithelioid granulomas with extensive necrosis along with Langhan's giant cells (Fig. 2). No band like infiltrate was noted at the dermo-epidermal junction. No palisading of histiocytes was seen or presence of mucin noted. Ziehl-Nielson stain was negative for acid-fast bacilli. Nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the biopsy taken from the nodule over the leg was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (amplification product of size 123 base pairs).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph of skin biopsy (H&E) shows dermis with large coalescing granulomas with extensive necrosis (4×). Inset (100×) shows granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and Langhan's giant cells (100×).

In view of clinicopathological features, he was started on standard antituberculous regimen consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. At the end of four weeks of antitubercular treatment most of the nodular lesions and pedal edema regressed (Fig. 3). Presently, the patient has completed five months of ATT with no relapse of skin lesions.

Fig. 3.

Complete regression of skin lesions after five weeks of antitubercular treatment.

Discussion

The concept of tuberculids was introduced by Darier in 1896, representing a form of cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculosis antigens in individuals with significant immunity.1 The entity papulonecrotic tuberculid was first established by Pautrier in 1936 as a distinct tuberculosis-associated disorder, when he described the characteristic clinical and histopathologic features. The characteristic lesions are small, erythematous, hard, dusky red, inflammatory papules that undergo central ulceration and heal spontaneously within weeks, sometimes leaving behind a atrophic varioliform scar.2 Papulonecrotic tuberculid-like lesions have also been mentioned to be associated with other mycobacterial infections, including Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium kansasii, and from BCG vaccination.3

Lesions arise in symmetric crops, typically with a predilection for acral extensor surfaces, although widespread involvement may be present. Lymphadenopathy, phlyctenular conjunctivitis, uveitis and leukocytoclastic vasculitis are the associated clinical features that have been described with the entity.4

Papulonecrotic tuberculids are diagnosed on the basis of typical clinical features along with a strongly positive Mantoux test, a tuberculoid histology with endarteritis and thrombosis of the dermal vessels and response to antitubercular treatment.5

Histopathological findings vary from a picture of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in early lesions to mature granuloma formation in older ones. Numerous conditions like pityriasis lichenoides acuta, syphilides, miliary tuberculosis, perforating granuloma annulare and suppurative folliculitis can be confused both clinically and histopathologically. Mycobacteria in tuberculid lesions is difficult to identify by either microscopy or culture due to the presence of very small numbers of bacilli, which are rapidly destroyed on arrival or removed from the body by a local delayed hypersensitivity reaction.6

M. tuberculosis DNA analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has better sensitivity than culture techniques. This finding has been reported in various studies with percentages between 50% and 100% positive.7 However, negative result does not exclude the diagnosis. IFN-gamma release assay has also been mentioned to detect latent tuberculous infection where PCR was negative.8

Treatment should be with full specific antitubercular therapy and use of single drug regimens is to be discouraged. Relapses have been reported in literature in spite of administering multi-drug therapy for 9 months, hence an aggressive search needs to be carried out to hunt for the extra-cutaneous focus.9,10

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Yates V.M., Rook G.A.W. Mycobacterial infections. In: Burns T., Breathnach S., Cox N., Griffiths C., editors. Rook's Text Book of Dermatology. 8th ed. Blackwell Science; Oxford: 2010. 31.1–31.30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordaan H.F., van Niekerk D.J., Louw M. Papulonecrotic tuberculid: a clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical study of 15 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:474–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iden D.L., Rogers R.S., 3rd, Schroeter A.L. Papulonecrotic tuberculid secondary to Mycobacterium bovis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(4):564–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dar N.R., Raza N., Zafar O., Awan S. Papulonecrotic tuberculids associated with uveitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeyakumar W., Ganesh R., Mohanram M.S., Shanmugasundararaj A. Papulonecrotic tuberculids of the glans penis: case report. Genitourin Med. 1988;64:130–132. doi: 10.1136/sti.64.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degitz K., Steidl M., Thomas P., Plewig G., Volkenandt M. Aetiology of tuberculids. Lancet. 1993;341:239–240. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90101-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quirós E., Bettinardi A., Quirós A., Piédrola G., Maroto M.C. Detection of mycobacterial DNA in papulonecrotic tuberculid lesions by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Lab Anal. 2000;14:133–135. doi: 10.1002/1098-2825(2000)14:4<133::AID-JCLA1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka R., Matsuura H., Kobashi Y. Clinical utility of an interferon -γ-based assay for mycobacteria detection in papulonecrotic tuberculid. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:169–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kullavanjiya P., Srimachan S., Suvantaroj S. Papulonecrotic tuberculid: necessity of long-term triple regimens. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:487–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madnani N.A. Papulonecrotic tuberculid – relapse after treatment. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1998;64:297–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]