Abstract

Background

Right Ventricle fractional area of change (RV FAC) is a quantitative two- dimensional echocardiographic measurement of RV function. RV FAC expresses the percentage change in the RV chamber area between end-diastole (RVEDA) to end-systole (RVESA). The objectives of this study were to determine the maturational (age- and weight- related) changes of RV FAC and RV areas and to establish reference values in healthy preterm and term neonates.

Methods

A prospective longitudinal study was conducted in 115 preterm infants (23-28 weeks gestational age at birth, 500-1500 gram). RV FAC was measured at 24 hours of age, 72 hours of age, 32 weeks and 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA). The maturational patterns of RVEDA, RVESA, and RV FAC were compared to 60 healthy full term infants in a cross sectional study (> 37 weeks, 3.5 +/− 1 kg), who received echocardiograms at birth (n=25) and one month of age (n=35). RVEDA and RVESA were traced in the RV focused apical 4-chamber view, and FAC was calculated using the formula: 100 * [(RVEDA – RVESA)/RVEDA)]. Premature infants that developed chronic lung disease or had a clinically and hemodynamically significant PDA were excluded (n=55) from the reference values. Intra- and inter- observer reproducibility analysis was performed.

Results

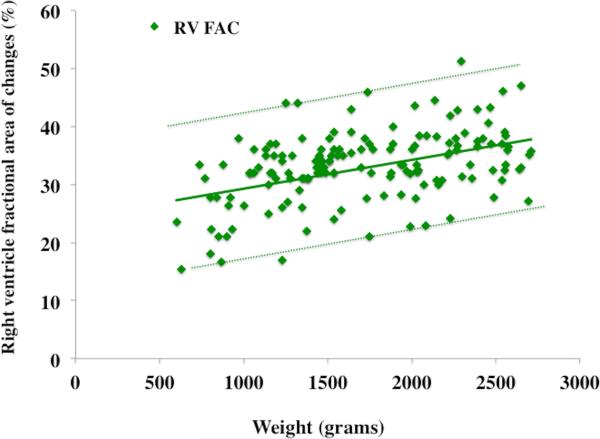

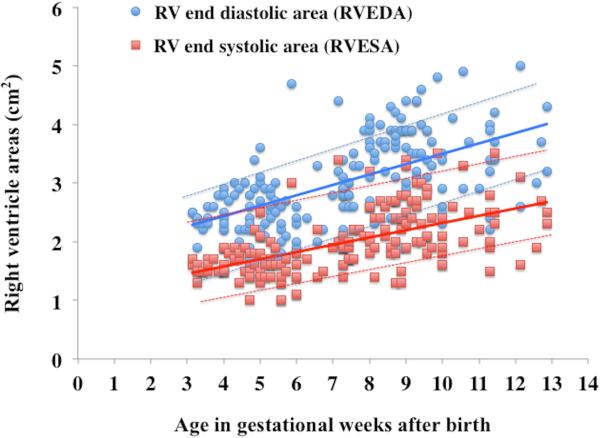

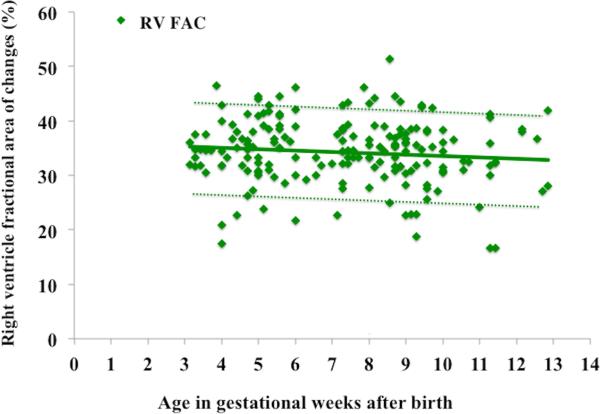

RV FAC ranged from 26% at birth to 35% by 36 weeks PMA in preterm infants (n=60) and increased almost two times faster in the first month of age as compared to healthy term infants (n=60). Similarly, RVEDA and RVESA increased throughout maturation in both term and preterm infants. RV FAC and RV areas correlated with weight (r=0.81, p<0.001), but were independent of gestational age at birth (r=0.3, p=0.45). RVEDA and RVESA correlated with PMA in weeks (r=0.81, p<0.001). RV FAC trended lower in preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (p=0.04), but did not correlate to size of PDA (p=0.56). There was no difference in RV FAC based on gender or need for mechanical ventilation.

Conclusions

This study establishes reference values of RV areas (RVEDA and RVESA) and RV fractional area of change (RV FAC) in healthy term and preterm infants and tracks their maturational changes during postnatal development. These measures increase from birth to 36 weeks PMA, and this is reflective of the postnatal cardiac growth as a contributor to the maturation of cardiac function These measures are also linearly associated with increasing weight throughout maturation. This study suggests that two-dimensional RV FAC can be used as a complementary modality to assess global RV systolic function in neonates and facilitates its incorporation into clinical pediatric and neonatal guidelines.

Keywords: Right Ventricle, Fractional Area of Change, Cardiac function, Neonates, Prematurity

Introduction

Right ventricular (RV) performance is an important determinant of clinical status and long-term outcome in preterm and term neonates with cardiopulmonary pathology.1,2 Right ventricular mechanics begin to undergo maturational changes in the early postnatal period that have long-term influence on cardiac function.1 Preterm birth is associated with global alterations in myocardial structure and function by adult age, including smaller RV size and greater RV mass than normal. Intuitively, alterations in RV function in the first months of age may serve both as a sensitive marker of altered hemodynamics, as well as of the onset of clinical and subclinical cardiorespiratory dysfunction.1,3-5 Therefore, early assessment of RV performance, in healthy and critically ill preterm infants, is essential for the surveillance in the early neonatal period.6

Recent pediatric and neonatal echocardiographic guidelines recommend performing quantitative measurements of RV systolic function using at least one of the following echocardiographic measures: (1) RV fractional area change (RV FAC), (2) tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), or (3) RV myocardial performance index (RV MPI).7-10 Normal values for TAPSE and RV MPI have previously been established in separate studies of healthy children, neonates and preterm infants, however, there are no reference normal data in children or neonates for RV FAC.6,7,11-13

The structural and functional organization of the RV has a complex three-dimensional myofiber arrangement.12 The dominant longitudinal shortening of the RV provides the major contribution to RV EF and stroke volume during systole and there is a strong association between RV FAC measured by echocardiography and RV EF determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).14-17 RV FAC that describes this longitudinal shortening on a global level may provide a sensitive measure of RV function in neonates. RV FAC as an echocardiographic tool to assess RV systolic function has been applied in adults15,17-19 children, and neonates.16,20,21 However, the reference values for the controls cohorts for the pediatric studies refer to those for adults.5,10,15,17,18,22 Utilization of RV FAC in children and neonates requires knowledge of the range of normal values specific to these patient populations as well as the variations due to maturational changes before routine clinical applications of RV FAC can be implemented in neonates.23

Therefore, the aims of this study were to determine the maturational (age- and weight- related) changes of RV area and RV FAC in preterm infants, compare the evolution with term infants, and establish normal reference values in both preterm and term neonates.

Methods

Study population

Preterm Infants

One hundred and fifteen preterm infants (born between 23 0/7 and 28 6/7 weeks gestation) were prospectively enrolled from among infants participating in the Premature and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP) (Clinical Trials number: NCT01435187). All the infants were enrolled at Washington University / St. Louis Children's Hospital neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) between August 2011 and August 2013. All 115 preterm infants received echocardiograms at 32 and 36 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA). The timings of the echocardiograms at 32 weeks and 36 weeks PMA were carefully selected to avoid the early postnatal period of clinical and cardiopulmonary instability and early mortality associated with extreme preterm birth. Choosing to study all infants at a common PMA optimizes the determination of the impact of gestational and chronological age on cardiac function at a specific developmental stage, and allows for the analysis of measures by post-gestational weeks from birth.24 To evaluate the pattern of longitudinal maturation by gestational age at birth and birth weight, 30 out of the 115 infants received echocardiograms at two additional time points, 24 hours and 72 hours of age. In these 30 infants, we tracked the maturational patterns at 24 hours of age, 72 hours of age, 32 weeks PMA, and 36 weeks PMA. Available patient clinical and demographic characteristics were obtained at each time point and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of premature infants

| Timing of Echocardiograms | 24 hours of age | 72 hours ofage | 32 weeks PMA | 36 weeks PMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants recruited at each time point | 30 | 30 | 115 | 115 |

| Infants included in reference values* | 20 | 20 | 60 | 60 |

| Gestational age at birth | 27 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 26 ± 2 | 26 ± 2 |

| Weight at birth | 915 ± 118 | 915 ± 118 | 899 ± 218 | 899 ± 218 |

| Weight at exam | ||||

| Male/female | 9/11 | 9/11 | 27/33 | 27/33 |

| Antentatal Steriods | 17/20 | 17/20 | 53/60 | 53/60 |

| Surfactant | 20/20 | 20/20 | 60/60 | 60/60 |

| Respiratory | ||||

| Weight (kg) at echocardiogram | 858 ± 111 | 814 ± 140 | 1400 ± 238 | 2192 ± 297 |

| RR (breaths/min) | 52 ± 7 | 48 ± 11 | 52 ± 9 | 50 ± 9 |

| Invasive Mechanical ventilaion | 17/30 | 14/30 | 1/115 | 0/115 |

| Bronchopulmnary dysplasia (BPD) | ||||

| No/Mild | 21/30 | 21/30 | 60/115 | 60/115 |

| Moderate/Severe* | 9/30 | 9/30 | 55/115 | 55/115 |

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| PDA | 27/30 | 23/30 | 19/115 | 11/115 |

| Small | 17 | 13 | 13 | 8 |

| Moderate* | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Large* | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| HR (beats/minute) | 159 ± 14 | 164 ± 12 | 148 ± 16 | 146 ± 11 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 50 ± 10 | 59 ± 10 | 73 ± 10 | 80 ± 9 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 33 ± 7 | 37 ± 9 | 42 ± 9 | 46 ± 10 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 39 ± 7 | 44 ± 8 | 49 ± 14 | 55 ±14 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

PMA, postmenstrual age; RR, respiratory rate; PDA, patent ductous arteriousous

SBP, Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP, Diastolic Blood Pressure; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure

Infants with a moderate or large PDA at 24 or 72 hours of age, or any size PDA at 32 or 36 weeks PMA were excldued from the reference values. Infants requiring respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA, classified as modertae or severed BPD, were also excluded from the reference values.

Note: All the demographic and clinical characteristics are from the infants included in the reference values.

Inclusion criteria included preterm infants born between 23 0/7 weeks and 28 6/7 weeks gestational age and alive at one year of age. Infants with any suspected congenital anomalies of the airways, congenital heart disease (except hemodynamically insignificant ventricular or atrial septal defects), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) or small for gestational age (SGA) were excluded from the study. Infants with qualitative right or left ventricular systolic dysfunction and/or echocardiographic signs of pulmonary hypertension (i.e. unusual degree of right ventricular hypertrophy, flat septum or elevated tricuspid regurgitation velocity) were also excluded from the reference values.

Patient with a clinically and hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), defined as moderate to large PDA, were excluded from the reference values.25 We used the relationship of the PDA to LPA to define size and clinical significance. Large = PDA:LPA ratio > 1; Moderate = PDA:LPA ratio of < 1 but > 0.5; and small = PDA:LPA < 0.5. Spontaneous closure of the PDA in extremely low gestational age neonates may not occur in the first week of life, and this delayed closure may be a physiological consequence of increased pulmonary vascular resistance from pulmonary immaturity.25 Infants with a moderate to large PDA based on its relationship to the left pulmonary artery (LPA) have a 15-times greater likelihood of requiring treatment for clinically and hemodynamically significant PDA than those with a small PDA.25 We therefore excluded infants with a moderate to large PDA in the first four days of age and any size PDA at 32 and 36 weeks PMA from the reference values.

Only infants with ‘respiratory healthiness’ were included for analysis.7,26 In the first few months of age, the definition of ‘respiratory healthiness’ may become difficult as a large majority of premature infants present with acute respiratory failure after birth and often require some sort of respiratory support up to 36 weeks PMA. Respiratory disease syndrome (RDS) and the need for mechanical ventilation are common in preterm birth in the early postnatal period. Moderate and severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), defined as the need for persistent supplemental oxygen support at 36 weeks PMA, is recognized as the most significant respiratory consequence of premature birth in the late postnatal period.26,27 Therefore, infants with any need for oxygen supplementation at 36 weeks PMA, classified as moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, were excluded from the reference values.26 We assessed for the contributions of mechanical ventilation and RDS, as well as BPD, as defined by 2001 National Institute of Healthy BPD workshop definition (Appendix 1), in a sub-analysis from birth through 36 weeks PMA.

Healthy term infants

RV areas and RV FAC were acquired in 60 healthy full term infants enrolled as a control cohort from the St. Louis Children's Hospital newborn nurseries. These infants were enrolled from a control group from the PROP study and from a control cohort enrolled through the Maternal Lipid Metabolism and Neonatal Heart Function in Diabetes, (Clinical Trials number: NCT01346527). Twenty-five infants received echocardiograms at birth (5 ± 3 days) and 35 separate infants at one month of age (30 ± 7 days). Infants were included from each study if they were > 37 weeks gestational age at birth. Patients were excluded in they required oxygen supplementation or respiratory support in the first month of age, had abnormal chest radiographs, or were diagnosed with congenital heart defects other than patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or patent foramen ovale. We compared the maturational patterns from birth to one month of age with the observed patterns in preterm infants.

We obtained informed written consent from all the parents in each study and the institutional review board of Washington University approved the studies.

Echocardiographic analysis of fractional area of change

Standard echocardiograms were acquired in the resting state without sedation by one designated experienced primary pediatric cardiac sonographer (T.S.) Two-dimensional, real-time, gray scale images were acquired by a commercially available ultrasound imaging system (Vivid 7 or 9, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). The images were obtained using a transducer centered frequency phased-array probe (ranging between 7.5 MHz and 12 MHz) and optimized to visualize the myocardial walls. Two-dimensional images were acquired from the RV focused apical 4-chamber view utilizing a previously published protocol for right ventricle image acquisition and data analysis.9,24 The image data was digitally stored for three cardiac cycles in cine loop format for offline analysis by vendor-customized semi-automated software analysis program (EchoPAC™ version 110.0.x; General Electric Medical Systems, Horten, Norway).

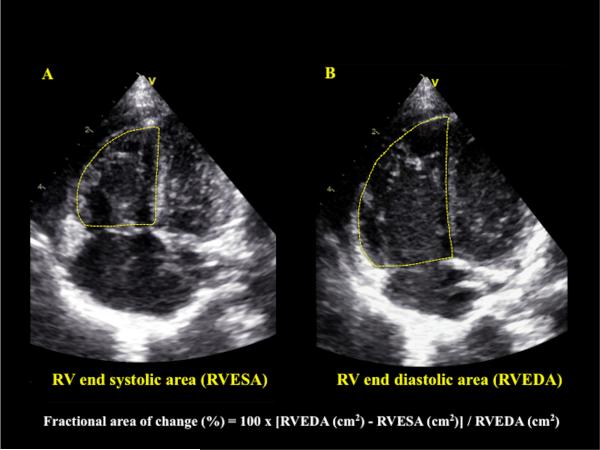

RVESA and RVEDA were measured in the RV focused apical four-chamber view. Beats with similar RR intervals were used to minimize errors in calculation.2 The RVESA and RVEDA were measured at the frames just before tricuspid valve opening and just after the valve closure, respectively.5,10 A ‘sail sign’ was traced from the (i) septal side of the tricuspid annular plane (septal-tricuspid annular hinge point) to (ii) apical-septal point and then to the (iii) RV free wall side (RVFW) of the tricuspid annular plane (lateral-tricuspid annular hinge point).24,28 The trabeculations were included in the RV area measurements to avoid underestimating the areas.9,12,29 The RV endocardial areas were delineated for three consecutive cardiac cycles and the mean of the three values were used to compute FAC.29 The RV FAC was automatically calculated from the EchoPAC™ software analysis as follows: 100 x [RV end-diastolic area (cm2) – RV end-systolic area (cm2)]/ RV end-diastolic area (cm2), (Figure 1). 4,9,14

Figure 1. Calculation of RV FAC.

This is an example of how to generate and calculate right ventricular fractional area change (RV FAC). RV FAC was obtained by tracing the RV endocardium in A) end-systole (RV end systolic area, RVESA) and B) end-diastole (RV end diastolic area, RVEDA). For RVESA and RVEDA, a ‘sail sign’ was traced from the septal side of the tricuspid annular plane (septal-tricuspid annular hinge point) to (ii) apical-septal point and then to the (iii) RV free wall side (RVFW) of the tricuspid annular plane (lateral-tricuspid annular hinge point).24,28 Care was taken to include the trabeculations in the measurements of the area by tracing the RVEDA and RVESA between RV trabeculations and the compact layer of the ventricle.9,12,29 The RVESA and RVEDA were measured at the frames just before tricuspid valve opening and just after the valve closure, respectively.5,10 Fractional area of change = 100 x ((RVEDA (cm2) - RVESA (cm2)) / RVEDA (cm2).

Reproducibility

To consider intra- and inter- observer variability, RVEDA, RVESA, and RV FAC were measured in 50% of the preterm (n=60) and term (n=30) infants by two investigators (P.T.L. and B.D.), both of whom were blinded to patient demographic and clinical data. Each observer utilized the same measurement protocol and was blinded to the other's results.24 The images used for the reproducibility analysis in the preterm population were randomly chosen from all four time points and included both healthy preterm infants and those infants that developed BPD or had a clinically and hemodynamically significant PDA. The reproducibility analysis was based on a combination of Bland- Altman plot analysis (percentage bias, 95% limits of agreements) and coefficient of variation (CV).30,31 The strength of agreement between the intra- and inter-observations was evaluated by simple linear regression analysis (Pearson's correlation). A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Statistical Methods

All data are expressed as mean ± SD or as percentages. Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and a histogram illustration of the data. Analysis of variance and student t-tests were used to compare the changes in RV areas and RV FAC from birth to 36 weeks PMA in the preterm infants and to compare the patterns to the healthy full term infants between birth and one month of age. Mann-Whitney test was used when normal distribution was not achieved. The correlation between the measures and gestational age and birth weight were analyzed with Pearson's correlation coefficient. A stepwise multiple regression was used to estimate RV FAC, RVEDA, and RVESA from postnatal age (in weeks), weight, and gender. We used p < 0.05 as statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using statistical software (SPSS version 14.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the preterm patients are summarized and compared in Table 1. Weight, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and mean arterial blood pressure increased from birth to 36 weeks PMA and the heart rate decreased, as expected (Table 1).

Maturational patterns of RV areas and RV FAC

In preterm infants, RV FAC ranged from 26% at birth to 35% by 32 weeks PMA (4-8 weeks of age). In the healthy full term infants RV FAC (p<0.001) increased linearly from 33% at birth to 39% at one month of age (Table 2). RV FAC in preterm infants increased almost two times faster in the first month of age as compared to healthy term infants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Change in RV areas and fractional area of change in the first month of age

| Birth | One month | Slope of change | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full term | (n=25) | (n=35) | ||

| RVEDA (cm2) | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| RVESA (cm2) | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| RV FAC | 33 ± 5 | 39 ± 4 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Preterm Infants | (n=20) | (n=20) | ||

| RVEDA (cm2) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| RVESA (cm2) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| RV FAC | 26 ± 4 | 35 ± 5 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

RVEDA, Right ventricle end diastolic area

RVESA, Right ventricle end systolic area

RV FAC, Right ventricle fractional area of change

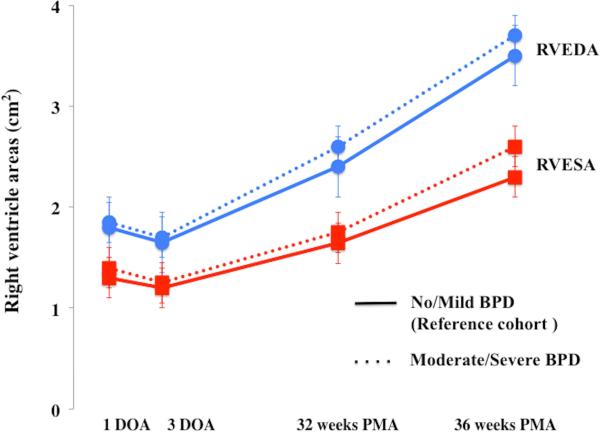

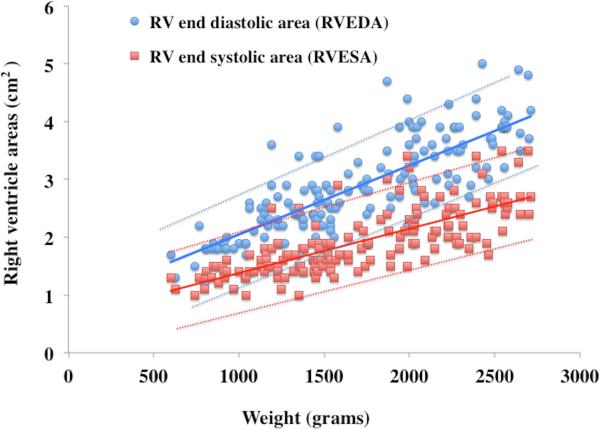

Maturational patterns of RV Areas and RV FAC in healthy preterm infants

Overall, RV areas and RV FAC increased from birth to 36 weeks in preterm infants (p<0.001) (Figure 2). A time specific maturational pattern revealed that RVEDA and RVESA were stable (p=0.37) between 24 hours and 72 hours of age. Both increased linearly between 72 hours to 32 weeks PMA and also between 32 to 36 weeks PMA. (Figure 2A). However, there was differential rate of growth for the two RV areas between 72hrs and 32 weeks PMA (Figure 2A). RVEDA increased 2.6 times more rapidly than RVESA resulting in an overall increase in RV FAC. As a result, RV FAC increased from 26% ± 4 at birth to 35% ± 4 (p<0.001) at 32 weeks PMA (Figure 2B). Both RVESA and RVEDA increased at a similar rate between 32 and 36 weeks PMA resulting in a constant RV FAC between 32 and 36 weeks PMA (p=0.92) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Maturational patterns of RV areas and fractional area of change.

(A) RV areas: From one to three days of the age (DOA) there was no difference in right ventricle end diastolic area, RVEDA, (blue circles with blue lines) and right ventricle end systolic area, RVESA, (red squares with red lines) between the reference cohort (infants with mild or no BPD, solid lines) and the infants with moderate or severe BPD (dotted lines). However, by 32 weeks PMA there was a statistically significant increase in RVEDA and RVESA (p=0.034) amongst the infants with moderate or severe BPD. From 32 to 36 weeks PMA, RVEDA increased at the same rate between the groups, but RVESA increased more rapidly in the infants with moderate or severe BPD. (B) RV FAC: Initially, at one and three DOA there were no statistical differences in the RV FAC (p=0.902), between the reference cohort (No or mild BPD, green diamonds with solid green line) and the infants with moderate or severe BPD (green diamonds with dotted green line). However, by 32 weeks PMA, RV FAC was decreased in infants with moderate and severe BPD as compared to the reference cohort.

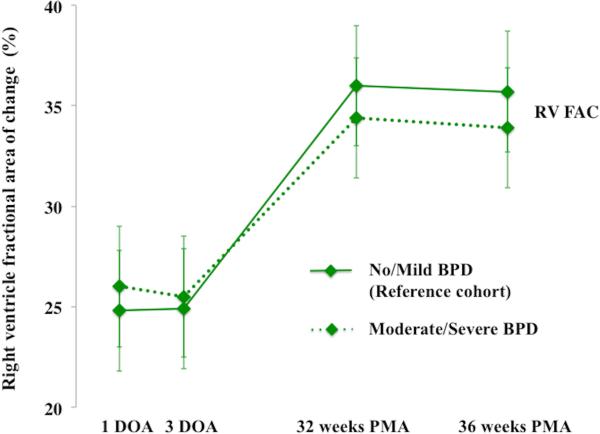

RVEDA, RVESA, and RV FAC were analyzed for the effect of birth weight and gestational age-related effects using percentile charts (mean ± 2 SD).7 The RV areas and RV FAC were linearly associated with birth weight (r=0.78, p=0.001) but not with gestational age at birth (r=0.43 p=0.52). RVEDA, RVESA, and RV FAC were further analyzed at 32 and 36 weeks PMA in all 60 healthy preterm patients to produce postnatal age- and weight-related percentile charts (mean ± 2 SD), (Figure 3 and Figure 4). RVEDA and RVESA were associated with both increasing weight (r=0.84, p<0.001, Table 3) and postnatal age (r=0.72, p<0.001, Table 4). RV FAC was only associated with increasing weight (r=0.68, p=0.01), but not with postnatal age beyond one month (r=0.15, p=0.61).

Figure 3. Weight related percentile charts in preterm neonates.

Weight versus observed mean value of (A) RVEDA (blue circles with blue lines), RVESA (red squares with red lines) and (B) RV FAC (green diamonds with green lines). The mean is indicated by solid lines, the errors bars ± 2SD are indicated by dotted lines.

Figure 4. Post-gestational Age (in weeks) related percentile charts in preterm neonates.

Age after birth versus observed mean value (A) RVEDA (blue circles with blue lines), RVESA (red squares with red lines) and (B) RV FAC (green diamonds with green lines). The means are indicated by solid lines, the error bars ± 2SD are indicated by dotted lines.

Table 3.

RV areas and fractional area of change in preterm infants by weight

| Weight (grams) | Infants (n) | RVEDA (cm2) | RVESA (cm2) | RV %FAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600 | 3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 23 ± 2 |

| 700 | 3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 29 ± 8 |

| 800 | 6 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 27 ± 5 |

| 900 | 6 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 28 ± 7 |

| 1000 | 5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 36 ± 6 |

| 1100 | 11 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 34 ± 5 |

| 1200 | 10 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 34 ± 6 |

| 1300 | 13 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 34 ± 6 |

| 1400 | 14 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 33 ± 4 |

| 1500 | 13 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 36 ± 4 |

| 1600 | 4 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 37 ± 5 |

| 1700 | 10 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 36 ± 5 |

| 1800 | 5 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 33 ± 4 |

| 1900 | 6 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 34 ± 4 |

| 2000 | 9 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 35 ± 6 |

| 2100 | 5 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 37 ± 6 |

| 2200 | 8 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 37 ± 7 |

| 2300 | 8 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 35 ± 4 |

| 2400 | 6 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 36 ± 5 |

| 2500 | 7 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 34 ± 7 |

| 2600 | 4 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 34 ± 5 |

| 2700 | 4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 36 ± 3 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

RVEDA, Right ventricle end diastolic area

RVESA, Right ventricle end systolic area

RV FAC, Right ventricle fractional area of change

Table 4.

RV areas and fractional area of change in preterm infants by age

| Age (weeks) | Infants (n) | RVEDA (cm2) | RVESA (cm2) | RV %FAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 40 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 26 ± 4 |

| 4 | 20 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 35 ± 5 |

| 5 | 19 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 35 ± 3 |

| 6 | 10 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 35 ± 6 |

| 7 | 12 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 35 ± 5 |

| 8 | 14 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 35 ± 3 |

| 9 | 19 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 35 ± 4 |

| 10 | 12 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 34 ± 3 |

| 11 | 7 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 34 ± 4 |

| 12 | 3 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 33 ± 5 |

| 13 | 4 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 35 ± 3 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

RVEDA, Right ventricle end diastolic area

RVESA, Right ventricle end systolic area

RV FAC, Right ventricle fractional area of change

Maturational patterns of RV areas and RV FAC in healthy full term infants

In the healthy full term infants RVEDA and RVESA also increased from birth to one month of age (p<0.001). RVEDA increased 1.5 times faster than RVESA over this time period resulting in a linear increase of RV FAC (p<0.001) from birth (33 ± 4 %) to one month of age (39 ± 5%) (Table 1). RV FAC increased 1.8 times faster over the first month of age in preterm infants. There was no significant relationship of RVEDA and RVESA with birth weight or gestational age in the healthy full term infants.

Confounding cardiopulmonary factors

Patent ductus arteriosus

A PDA was present in 27 out of 30 patients (90%) at 24 hours of age and 20 out of 30 patients (67%) at 72 hours of age. The size of the PDA was independently graded from small to large by two observers and the results are listed in Table 1.25 In the first four days of age, twenty patients had either no PDA or a small PDA and were therefore included in the analysis for the reference values. There was no significant relationship between the size of the PDA and RV FAC (p=0.32). However RVEDA and RVESA were larger with increasing size of the PDA (p=0.002 and p=0.007, respectively), (Table 5). None of the measures were predictive of which infants would require medical (n=7) and/or surgical therapy (n=2) to manage the PDA (p=0.35). At 32 weeks PMA 19/115 infants still had PDA (1 large, 5 Moderate, 13 small) and at 36 weeks PMA 11/115 infants had a PDA (3 moderate, 8 small). Patients with any size PDA at 32 or 36 weeks PMA were excluded from the reference values analysis. There was no difference between the maturational patterns of RV FAC, RVEDA, or RVESA in infants who still had PDA at 32 or 36 weeks PMA (corrected for age, gender, and PDA size) vs. those who did not have a PDA, (p=0.26).

Table 5.

RV areas and fractional area of change by PDA size

| No PDA (n=10) | Small (n=30) | Moderate (n=11) | Large (n=9) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVESA (cm2) | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.002 |

| RVEDA (cm2) | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.007 |

| RV FAC | 27 ± 3 | 26 ± 7 | 26 ± 5 | 25 ± 5 | 0.5 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

PDA, Patent ductous arteriosus

RVEDA, Right ventricle end diastolic area

RVESA, Right ventricle end systolic area

RV FAC, Right ventricle percent fractional area of change

Respiratory distress syndrome and bronchopulmonary dysplasia

There was no significant difference in RV areas or RV FAC at 24 and 72 hours of age between infants who required mechanical intervention and those that required non-invasive respiratory support (p=0.56). All of the preterm infants received surfactant and 80% of their mothers received antenatal steroids. Moderate or severe BPD was diagnosed in 48% (55/115) of the infants. Infants with no BPD or with mild BPD required no respiratory or oxygen support at 36 weeks PMA. Therefore, we categorized the infants into two groups: Group 1 (n = 60) included infants with no or mild BPD and Group 2 (n = 55) with moderate or severe BPD. Initially, at 24 hours and 72 hours of age, there were no statistical differences in the RV FAC (p=0.902), RVEDA (p=0.145), and RVESA (p=0.102) between the two groups. However, by 32 weeks PMA there was a statistically significant increase in RVEDA (p=0.026) and RVESA (p=0.034) in Group 2 infants with moderate or severe BPD as compared to Group 1 infants with mild or no BPD. From 32 to 36 weeks PMA, RVEDA increased at the same rate between the groups, but RVESA increased more rapidly in the Group 2 (moderate or severe BPD). As a result, RV FAC trended lower in Group 2 at 32 and 36 weeks PMA. There were no differences in the measurements between the groups at any time point when stratified by gender (p=0.45).

Feasibility and Reproducibility

The reproducibility analysis is summarized in Table 6. The measurements were feasible in 86% of the images using the methods previously described by our group for RV-focused image acquisition.24 For all three measurements, the bias was less than 10%, with narrow limits of agreement, small coefficients of variations, and good strength of associations as indicated by the linear correlation coefficient (r), (Table 6).

Table 6.

Reproducibility analysis

| Bland Altman |

Intraclass Correlation |

Agreement |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias (%) | LOA | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | CV (%) | r | p | |

| Intra- observer reproducibility | |||||||

| RVEDA | 6% | −0.7 | 0.97 (0.94-0.98) | 0.01 | 6.0% | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| RVESA | 2% | −0.8 | 0.90 (0.84-0.94) | 0.04 | 4.7% | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| RV FAC | 5% | −25.1 | 0.94 (0.91-0.96) | 0.02 | 11.0% | 0.52 | 0.01 |

| Inter- observer reproducibility | |||||||

| RVEDA | 6% | −0.9 | 0.93 (0.89-0.96) | 0.03 | 7.0% | 0.52 | 0.008 |

| RVESA | 8% | −1.1 | 0.93 (0.89-0.96) | 0.03 | 6.0% | 0.4 | 0.05 |

| RV FAC | 5% | −15.3 | 0.93 (0.89-0.96) | 0.03 | 8.0% | 0.76 | <0.001 |

LOA, limits of agreement; CV, Coeffieicent of Variartion; Agreement, Pearson's correlation

RVEDA, Right ventricle end diastolic area

RVESA, Right ventricle end systolic area

RV FAC, Right ventricle fractional area of change

Discussion

This study establishes reference values for RV end diastolic and end systolic areas (RVEDA and RVESA) and RV fractional area of change (RV FAC) in term and preterm infants and tracks their maturational changes during postnatal development. For premature infants, there is maturational linear increase for RVEDA and RVESA from birth to 36 weeks PMA and for RV FAC from birth to 32 weeks PMA, after remaining relatively constant in the first three days of age. This pattern of maturational changes in RV areas and systolic function is mirrored in full term infants in the first of month of age with a difference in rate of growth. The increase in RVEDA is more rapid than in RVESA in both preterm and full term infants, but the rates of increase in both RV areas are more rapid in preterm infants than in full term infants in the first month of postnatal age. The maturational changes in RV areas and systolic function in preterm infants are dependent on birth weight but not on gestational age at birth. The RV FAC in preterm infants reaches equivalency with full term infant by 32 weeks of PMA and then remains relatively unchanged in both, lending itself as a clinical tool for the assessment of RV function in neonates.

The evaluation of RV function by echocardiography has been limited by the lack of reliable quantitative parameter for the assessment of RV function.8,32,33 Recently TAPSE, MPI, and RV strain have been utilized in the assessment of RV function in neonates.7,24,33 This is the first study to demonstrate both the clinical feasibility of reliable measurements of RV areas and RV FAC in preterm and term infants and introduces its potential application as a quantitative diagnostic tool to assess maturational changes of RV function throughout early postnatal development.

Maturational patterns of RV areas and RV FAC

The transitional period in neonates is characterized by peak hemodynamic alterations in the transitional circulation from fetal to postnatal age (i.e. closure of fetal shunts, changes in cardiac output, systemic and pulmonary preload, afterload, and resistance).34,35 This study demonstrates that in this transitional period, RV areas and RV FAC were relatively unchanged in preterm infants (Figure 2A). Jain et al recently demonstrated that RV areas and RV FAC remains relatively stable in the transitional period in healthy term infants, but James et al observed that RVESA and RV FAC increases in the transitional period in preterm infants, while RVEDA remains stable.34,35 Although RV FAC may increase in the transitional period in preterm infants due to a smaller RV end systolic area, (as compared to health term infants) which likely reflect the decreased afterload imposed on the right ventricle by slowly decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance, we would suggest that the relative stability of the RV FAC in both healthy preterm and term infants may be attributed to simultaneous decrease in RV volume and afterload with little-to-no change in RV stroke volume or cardiac output in the first three days of age.12

The maturation of cardiac structure and function is a continued postnatal phenomenon that is dependent on time and growth. The maturational changes of RVEDA, RVESA, and RV FAC in the preterm infants are dependent on both postnatal weight, but independent of gestational age at birth (Figure 3). RVESA and RVEDA are also dependent on post gestational age in weeks, but RV FAC changes independently of gestational postnatal age (Figure 4). In the first four to eight weeks post-natal age in healthy preterm infants, there was an accelerated growth of the RV with linear increase in RVEDA and RVESA and relative increase in RV FAC, coinciding with the increasing postnatal age (Figure 4) and rapid somatic growth (Figure 3) during that period. Preterm infants experienced more rapid physiological increase in cardiac structure and function in the first four weeks of age than the term infants (Table 2). The more rapid growth of RV dimensions in preterm infants can partly be explained by the progressive increase in ventricular thickness of compact myocardium that initiates in the early embryonic looped heart and continues in the developing heart during fetal age.36 We speculate that this phenomenon continues in the early postnatal age with more rapid rate of ventricular growth in prematurely born infants than in full term infants.37

Multiple studies in adults have demonstrated that RV FAC determined either by MRI or by echocardiography correlated well with cardiac MRI derived RV EF.15,17-19,38 In children, however, there is controversy about the reliability of RV FAC as a marker of RV EF and its use in the assessment of RV systolic function. In separate studies, Lai et al and Srinivasan et al each demonstrated a weak correlation between RV FAC by echocardiography and MRI-derived RV volumes in children with a wide range of congenital heart defects.21,39 In contrast, several recent studies have successfully utilized RV FAC by echocardiography to monitor RV function in both neonates and children with congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, and sickle cell anemia.34,35,40-43 Alghamadi et al. demonstrated that the RV systolic and diastolic areas measured by echocardiography correlated well with systolic and diastolic volumes by MRI in pediatric patients with repaired Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).16 Alkon et al. observed that the RV FAC was decreased in children who developed pulmonary arterial hypertension as compared to a control cohort.44 Tweddell et al demonstrated in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome that lower pre-Norwood RV FAC was independently associated with transplantation.45

Clinical Implication of RV FAC in Neonates

During the first months of age RV function undergoes a physiological development that can be altered by a wide variety of conditions, such as, evolving bronchopulmonary dysplasia, persistent PDA, pulmonary hypertension, and many congenital and acquired heart diseases.12 Alterations in RV function can be valuable predictors of outcomes, but, the paucity of clearly defined quantitative parameters for functional assessment is a major impediment to early identification of the development of RV dysfunction in newborn infants.8,10,23,24,46 Based on our study, some important considerations should be undertaken when utilizing FAC as an index of RV global systolic function in preterm and full-term infants. The maturational changes that occur in the RV areas and RV FAC in the preterm infants are dependent on postnatal weight, but independent of gestational age at birth. RVESA and RVEDA are also dependent on post gestational age in weeks. Due to these maturational changes, it may be accurate not to use a single value throughout the population but rather reference the areas either by the weight or by the age in postnatal weeks, as Koestenberger et al elucidated with TAPSE.7 As the premature heart grows, the RV areas should continue to increase throughout maturation. Clinically the variations in the maturation of cardiac function in these infants, as determined by RV FAC, will occur based on the rate of change of the systolic and diastolic areas. With reference values, RV area and FAC can now be utilized in both preterm and full-term infants with a variety of cardiopulmonary pathologies.

Respiratory function

Infants with moderate or severe BPD are at a higher risk of developing pulmonary vascular hypertension that can lead to RV hypertrophy, dilatation, and RV dysfunction with subsequent RV failure.7,26 In this study 48% (55/115) had moderate or severe BPD by 36 weeks PMA. By 32 weeks PMA RV FAC trended lower in infants with moderate or severe BPD as compared to those infants with mild BPD or without BPD altogether (Figure 2B). By 32 weeks PMA there was also a significant increase in RVEDA and RVESA amongst the moderate and severe groups (Figure 2A). Although BPD is multifactorial and not only dependent on the changes in the pulmonary vasculature, this increase in RV Areas coupled with the decrease in function, as measured by RV FAC, are most likely due to the evolving BPD and not the maturational changes. RV FAC has already been shown to be a clinically applicable and feasible measure for monitoring RV function in adult and pediatric patients with pulmonary disease.20,47 Our current observation suggests that RV FAC, as a quantitative measure of change in right ventricular function, may offer insight into some of the pathophysiological mechanisms of BPD in this late postnatal period by providing new information in the patterns of cardiopulmonary development in preterm infants at risk for persistent respiratory support.

Patent ductus arteriosous

In this study we observed that the increasing size of the PDA in the first three days of age correlated with increased RV areas, but stable RV FAC. RV areas and RV FAC were not predictive of which infants would require medical or surgical therapy to manage the PDA. RVEDA and RVESA were larger with increasing size of the PDA, implying that the physiological effects of a persistent PDA may increase the RV areas, but RV global systolic function, as measured by RV FAC, is preserved regardless of size or presence of the PDA in this early postnatal period. The right ventricle initially pumps against the high vascular resistance in the lungs, potentially resulting in temporary morphological changes to its structure with preserved function.25 By 32 and 36 weeks PMA, infants with a PDA, regardless of size, age, or gender, had the same maturational patterns of RV areas and RV FAC as those infants who did not have a PDA.

Study limitations and future direction

A recognized limitation of all quantitative measures of RV function acquired from a single RV focused apical four-chamber view, especially RV FAC, is that one view does not yield a truly “global” measure of RV function.2,9,48 The RV is a complex tripartite structure and a single apical four-chamber view does not include the contribution of the RV outflow tract to ejection. In patients with certain congenital heart defects in which the RV outflow tract is affected more than other myocardial segments (i.e. TOF repair with a patch), or in the case of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy where the RV is not visualized well in the apical four camber view because of the dilated left ventricle, the RV FAC will result in overestimation or underestimation of global RV function.12 This may partially explain the controversy of the correlation of RV FAC to outcomes in the pediatric literature. Recently, several authors have outlined an approach for a global assessment of RV function that uses three RV–focused views, apical four-, three-, and two-chamber approach, to calculate true “global” measures of RV function, similar to their apical views of the left ventricle.2,34,35,48 However, until more rigorous studies acquire RV FAC using the three- chamber RV focused apical, the RV focused apical four-chamber view is still used as the primary method for clinical follow-up of children and neonates with RV dysfunction.9,10 We feel that the choice to use RV FAC and the specific focused views of acquisition in daily practice will depend on the clinical scenario and questions to be answered.12

The assessment of RV function from the apical four-chamber view is dependent on image quality, which can be problematic due to the complex tripartite geometry of the right ventricle, its thin wall myocardium, abundant trabeculations, and the inability to always visualize the entire RV free wall in the image sector.12,23 In neonates, however, it is easier to delineate the endocardial borders despite the highly trabeculated RV.4,9,24 Visualization of the endocardial borders is often limited in the RV lateral wall and RV apex, but can be corrected with the acquisition of the images in an RV focused apical four-chamber view using a consistent imaging protocol.9,24 We have previously demonstrated excellent reliability for cardiac deformation measures in preterm infants with this approach and use of this RV focused view serves to enhance RV FAC measurements in term and preterm infants.9,24 Calculation of RVEDA, RVESA, and RV FAC can be easily performed using standard echocardiographic equipment, and does not require any geometric assumptions.15 Although RV FAC is affected by loading conditions, it is also less sensitive to abnormal geometry and regional abnormalities.10

RV FAC% does not provide functional information at the regional level of the myocardium and only measures RV global systolic function. The observation that the pediatric and neonatal guidelines recommend MPI, TAPSE, and/or FAC, to quantitatively assess RV function in children and neonates probably indicates that no single measurement is perfect. With established reference values and maturational patterns, more studies are now needed to properly validate RV FAC in different clinical conditions within neonatology to assess its overall impact on management and outcomes.10,12,23

The preterm infants were prospectively followed longitudinally from birth to 36 weeks PMA, while the reference values for the term infants were developed from cross-sectional studies. The studies were designed around the different funding mechanisms. Although the ideal comparisons would have been if both the preterm and term cohorts were followed longitudinally, the measures of RV FAC in the cross sectional term cohort population the first days of life were similar to recently published measures by Jain et a 2014.35

Conclusions

This study establishes reference values for RV end diastolic and end systolic areas (RVEDA and RVESA) and RV fractional area of change (RV FAC) in term and preterm infants and tracks their maturational changes during postnatal development. These measures increase from birth to 36 weeks PMA and this is reflective of the postnatal cardiac growth as a contributor to the maturation of cardiac function These measures are also associated with increasing weight throughout maturation. This study suggests two-dimensional RV FAC can be used as a complementary modality to assess physiological changes of global RV systolic function in neonates and permits its incorporation into clinical pediatric and neonatal guidelines.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Premature and Respiratory Outcomes Program (NIH 1U01 HL1014650, U01 HL101794), NIH R21 HL106417, Pediatric Physician Scientist Training Grant (NIH 5 T32 HD043010-09), and Postdoctoral Mentored Training Program in Clinical Investigation (NIH UL1 TR000448).

Abbreviations

- RV

right ventricle

- FAC

fractional area change

- PMA

Post-menstrual age

- DOA

Days of age

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- MPI

myocardial performance index

- RVESA

end-systolic area

- RVEDA

end-diastole area

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- EF

ejection fraction

- TOF

Tetralogy of Fallot

Appendix 1: Definition of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia

There currently are multiple definitions for BPD. In this study we used the 2001 NIH workshop definition of BPD, the most commonly used and validated classification system.26 Modifications to these definitions may be proposed later from analyses of PROP follow-up data.

2001 NIH Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Workshop Definition

The 2001 NIH workshop on BPD developed a classification system that includes specific criteria for ‘mild,’ ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’ BPD and it has been shown that this definition is useful in predicting longer-term pulmonary and neurodevelopmental outcomes.26 The criteria are based on the need for supplemental oxygen at 28 days combined with the supplemental oxygen support at 36 weeks PMA. ‘Mild’ BPD is defined by, supplemental oxygen for > 28 days and on room air at 36 weeks PMA or at discharge. Moderate BPD is defined as supplemental oxygen for > 28 days and a need for supplemental oxygen < 30% at 36 weeks PMA/discharge. Severe BPD is defined as supplemental oxygen for > 28 days and a need for >30% oxygen or on nasal CPAP or mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks PMA. Extremely low gestational age neonates will be classified as having no BPD if they do not meet any of the above criteria.26

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Lewandowski AJ, Bradlow WM, Augustine D, Davis EF, Francis J, Singhal A, et al. Right Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction in Young Adults Born Preterm. Circulation. 2013;128:713–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajagopal S, Forsha D, Risum N, Hornik CP, Poms AD, Fortin TA, et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Right Ventricu lar Function in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension with Global Longitudinal Peak Systolic Strain Derived from Multiple Right Ventricular Views. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:657–65. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawut SM, Barr RG, Lima JAC, Praestgaard A, Johnson WC, Chahal H, et al. Right ventricular structure is associated with the risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)--right ventricle study. Circulation. 2012;126:1681–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.095216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jurcut R, Giusca S, La Gerche A, Vasile S, Ginghina C, Voigt JU. The echocardiographic assessment of the right ventricle: what to do in 2010? Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:81–96. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murase M, Ishida A, Morisawa T. Left and Right Ventricular Myocardial Performance Index (Tei Index) in Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants. Pediatr Cardio. 2009;30:928–35. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koestenberger M, Nagel B, Ravekes W, Urlesberger B, Raith W, Avian A, et al. Systolic Right Ventricular Function in Preterm and Term Neonates: Reference Values of the Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE) in 258 Patients and Calculation of Z-Score Values. Neonatology. 2011;100:85–92. doi: 10.1159/000322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertens L, Seri I, Marek J, Arlettaz R, Barker P, McNamara P, et al. Targeted Neonatal Echocardiography in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: practice guidelines and recommendations for training. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;10:1057–78. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudski LG1, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez L, Colan SD, Frommelt PC, Ensing GJ, Kendall K, Younoszai AK, et al. Recommendations for Quantification Methods During the Performance of a Pediatric Echocardiogram: A Report From the Pediatric Measurements Writing Group of the American Society of Echocardiography Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease Council. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:465–95. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberson DA, Cui W. Right ventricular Tei index in children: effect of method, age, body surface area, and heart rate. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:764–70. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mertens LL, Friedberg MK. Imaging the right ventricle—current state of the art. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:551–63. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czernik C, Rhode S, Metze B, Schmalisch G, Bührer C. Persistently Elevated Right Ventricular Index of Myocardial Performance in Preterm Infants with Incipient Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton KD1, Meece RW, Hill JC. Assessment of the Right Ventricle by Echocardiography: A Primer for Cardiac Sonographers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:776–92. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anavekar NS, Gerson D, Skali H, Kwong RY, Yucel EK, Solomon SD. Two-dimensional assessment of right ventricular function: an echocardiographic-MRI correlative study. Echocardiography. 2007;24:452–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alghamdi MH, Mertens L, Lee W, Yoo SJ, Grosse-Wortmann L. Longitudinal right ventricular function is a better predictor of right ventricular contribution to exercise performance than global or outflow tract ejection fraction in tetralogy of Fallot: A combined echocardiography and Magnetic Resonance Study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;14:235–9. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zornoff LAM, Skali H, Pfeffer MA, St John Sutton M, Rouleau JL, Lamas GA, et al. Right ventricular dysfunction and risk of heart failure and mortality after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1450–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anavekar NS, Skali H, Bourgoun M, Ghali JK, Kober L, Maggioni AP, et al. Usefulness of right ventricular fractional area change to predict death, heart failure, and stroke following myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul S, Tei C, Hopkins JM, Shah PM. Assessment of right ventricular function using two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1984;107:526–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bano-Rodrigo A, Salcedo-Posadas A, Villa-Asensi JR, Tamariz-Martel A, Lopez-Neyra A, Blanco-Iglesias E. Right ventricular dysfunction in adolescents with mild cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai WW, Gauvreau K, Rivera ES, Saleeb S, Powell AJ, Geva T. Accuracy of guideline recommendations for two-dimensional quantification of the right ventricle by echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24:691–98. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Candales A, Dohi K, Rajagopalan N, Edelman K, Gulyasy B, Bazaz R. Defining normal variables of right ventricular size and function in pulmonary hypertension: an echocardiographic study. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:40–5. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.059642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaul S, Miller JG, Grayburn PA, Hashimoto S, Hibberd M, Holland MR, et al. A suggested roadmap for cardiovascular ultrasound research for the future. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;24:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy PT, Holland MR, Sekarski TJ, Hamvas A, Singh GK. Feasibility and reproducibility of systolic right ventricular strain measurement by speckle-tracking echocardiography in premature infants. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:1201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos FG, Rosenfeld CR, Roy L, Koch J, Ramaciotti C. Echocardiographic predictors of symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus in extremely-low-birth-weight preterm neonates. J Perinatol. 2010;30:535–39. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–29. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown MK, DiBlasi RM. Mechanical ventilation of the premature neonate. Respir Care. 2011;56:1298–1311. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozcelik N, Shell R, Holtzlander M, Cua C. Decreased right ventricular function in healthy pediatric cystic fibrosis patients versus non-cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34:159–64. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnemains L, Stos B, Vaugrenard T, Marie P-Y, Odille F, Boudjemline Y. Echocardiographic right ventricle longitudinal contraction indices cannot predict ejection fraction in post-operative Fallot children. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:235–42. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koopmans LH, Owen DB, Rosenblatt JI. Confidence Intervals for the Coefficient of Variation for the Normal and Log Normal Distributions. Biometrika. 1964;51:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kluckow M, Seri I, Evans N. Echocardiography and the neonatologist. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:1043–7. doi: 10.1007/s00246-008-9275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alp H, Karaarslan S, Baysal T, Cimen D, Ors R, Oran B. Normal values of left and right ventricular function measured by M-mode, pulsed doppler and Doppler tissue imaging in healthy term neonates during a 1-year period. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:853–59. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain A, Mohamed A, El-Khuffash A, Connelly KA, Dallaire F, Jankov RP, et al. A Comprehensive Echocardiographic Protocol for Assessing Neonatal Right Ventricular Dimensions and Function in the Transitional Period: Normative Data and Z Scores. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James A, Corcoran D, Jain A, Mertens L, Mcnamara PJ, Franklin O, et al. Assessment of Myocardial Performance Using Novel Echocardiography Markers in Infants Less than 29 Weeks Gestation in the Transitional Period. Early Human Development. 2014;90:829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishiwata T, Nakazawa M, Pu WT, Tevosian SG, Izumo S. Developmental changes in ventricular diastolic function correlate with changes in ventricular myoarchitecture in normal mouse embryos. Circ Res. 2003;93:857–65. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100389.57520.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taber LA. Biomechanics of cardiovascular development. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2001;3:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.3.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Prakasa K, Bomma C, Tandri H, Dalal D, James C, et al. Comparison of novel echocardiographic parameters of right ventricular function with ejection fraction by cardiac magnetic resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:1058–64. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivasan C, Sachdeva R, Morrow WR, Greenberg SB, Vyas HV. Limitations of standard echocardiographic methods for quantification of right ventricular size and function in children and young adults. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:487–93. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szymanski P, Klisiewicz A, Lubiszewska B, Lipczynska M, Konka M, Kusmierczyk M, et al. Functional anatomy of tricuspid regurgitation in patients with systemic right ventricles. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:504–10. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qureshi N, Joyce JJ, Qi N, Chang R-K. Right ventricular abnormalities in sickle cell anemia: evidence of a progressive increase in pulmonary vascular resistance. J Pediatr. 2006;149:23–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petko C, Uebing A, Furck A, Rickers C, Scheewe J, Kramer HH. Changes of myocardial deformation and dyssynchrony in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome before and after the Norwood operation assessed by 2D speckle tracking. Cardiol Young. 2011;21:S114–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng EK, Spooner R, Young D, Danton MD. Acute B-type natriuretic peptide response and early postoperative right ventricular physiology following tetralogy of Fallot's repair. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:335–39. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alkon J, Humpl T, Manlhiot C, McCrindle BW, Reyes JT, Friedberg MK. Usefulness of the right ventricular systolic to diastolic duration ratio to predict functional capacity and survival in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:430–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tweddell JS, Sleeper LA, Ohye RG, Williams IA, Mahony L, Pizarro C, et al. Intermediate-term mortality and cardiac transplantation in infants with single-ventricle lesions: risk factors and their interaction with shunt type. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:152–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forsey J, Friedberg MK, Mertens L. Speckle tracking echocardiography in pediatric and congenital heart disease. Echocardiography. 2013;30:447–59. doi: 10.1111/echo.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schenk P, Globits S, Koller J, Brunner C, Artemiou O, Klepetko W, et al. Accuracy of echocardiographic right ventricular parameters in patients with different end-stage lung diseases prior to lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000;19:145–54. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forsha D, Risum N, Kropf PA, Rajagopal S, Smith PB, Kanter RJ, et al. Right Ventricular Mechanics Using a Novel Comprehensive Three-View Echocardiographic Strain Analysis in a Normal Population. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:413–22. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]