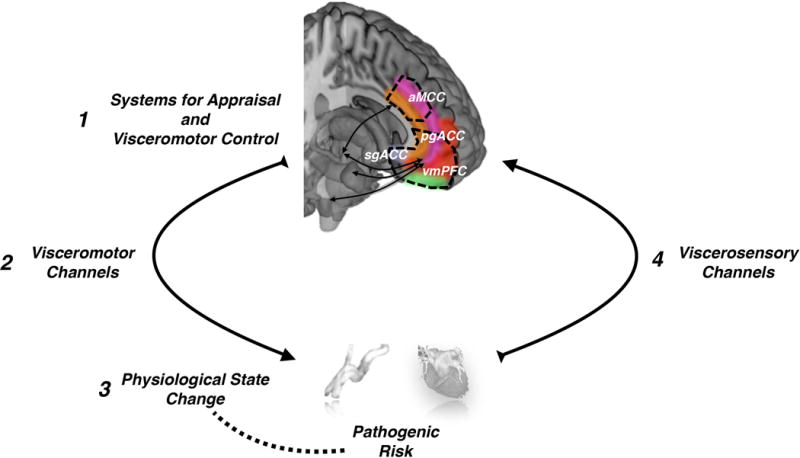

Figure 1.

Four core elements comprise at least one kind of brain-body pathway linking psychological stress and physiological stress reactions to physical health. The first encompasses networked brain systems that appraise internal and external sources of information as threats that tax or exceed coping resources and translate these appraisals into visceromotor commands. These systems likely include the anterior mid-cingulate cortex (aMCC), pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (pgACC), subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC), and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). The second encompasses visceromotor (e.g., autonomic nervous system) channels that translate appraisal-based neural commands into a change in an end organ state in the body (e.g., a rise in blood pressure and heart rate). A corollary of this third component is that the patterning of the end-organ state change (e.g., a sizeable and sustained rise in blood pressure or heart rate) should plausibly relate to disease progression or risk. For example, chronically large or prolonged rises in blood pressure may exert shear or tensile stress on blood vessel walls over time, possibly accelerating atherosclerosis and influencing risk for later heart disease. The fourth component encompasses viscerosensory (e.g., autonomic nervous system) channels that relay feedback signals from the body, enabling the representation of end organ state changes in the brain. The interaction between appraisal systems and visceromotor and viscerosensory channels may thus represent part of the possible basis for stress-health relationships.