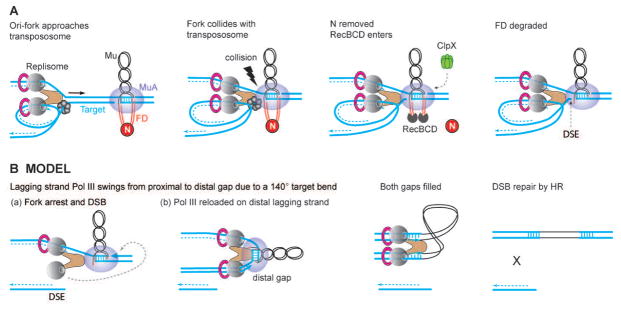

Fig. 7. Model depicting how the Mu transpososome first exploits incoming Pol III for just-in-time FD degradation, and next exploits Pol III stalled at the DSB for coordinated repair of both target gaps flanking Mu.

(A) Sequence of repair events as deduced in this, and in prior work (Choi & Harshey, 2010, Choi et al., 2014a). The Mu transpososome does not begin FD repair until the replication fork arrives. Interaction between the two complexes generates a ‘signal’ for N removal and RecBCD entry. The fork stalls because the transpososome is blocking its progress. (B) Scheme for how the DSB and the bent target is exploited for repair of both gaps during non-replicative Mu transposition. E. coli replisomes contain three polymerase molecules (Reyes-Lamothe et al., 2010), but only two are shown for clarity. When the polymerase stalls at the transpososome, the Pol III subunit on the lagging strand (or the extra third subunit) reloads on the distal gap brought into proximity by the hairpin target bend within the transpososome (Montano et al., 2012). As the polymerase moves forward, the transpososome is dislodged and both gaps are filled simultaneously. The DSE may not form until this step, but is shown earlier only to accommodate the target bend. A nuclease must trim the 4 nt flanks, and a ligase seal the remaining nicks. The DSE is repaired by homologous recombination (HR).