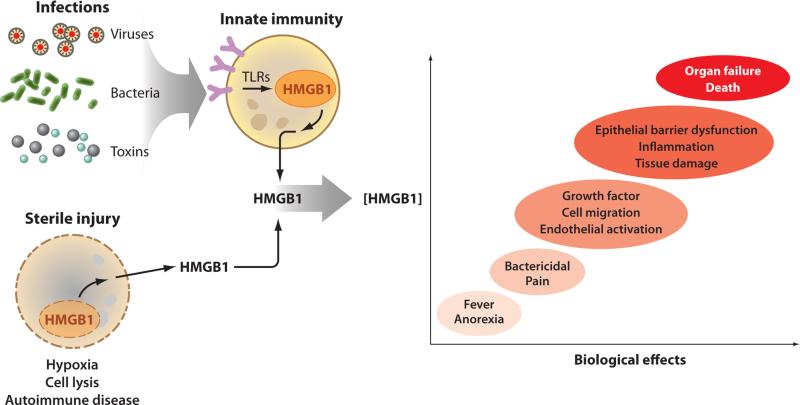

Figure 2.

HMGB1 is released during infection by activating innate immunity and during sterile injury as a passive phenomenon. Exposure to pathogens activates the highly conserved innate immune response, which triggers the release of HMGB1 from monocytes, macrophages, and other cells at the frontline of host defense. HMGB1 shuttles from the nucleus to the cytosol, where it accumulates in intracellular vesicles prior to secretion. This process can take up to 8 h to complete. The passive release of HMGB1 in cells undergoing necrotic cell death is much faster because HMGB1 is loosely attached to nuclear DNA in living cells. HMGB1 binding to chromatin increases during programmed cell death, causing some of it to be retained, but ingestion of apoptotic bodies by macrophages stimulates significant release of HMGB1 by the macrophages (not illustrated). Thus, infection, necrosis, and apoptosis can all lead to elevated HMGB1 levels. In low levels, HMGB1 mediates sickness behavior and antibacterial activities that contribute to inflammatory responses that can resolve. The release of larger amounts of HMGB1, however, is associated with the development of epithelial barrier failure, organ dysfunction, and even death.