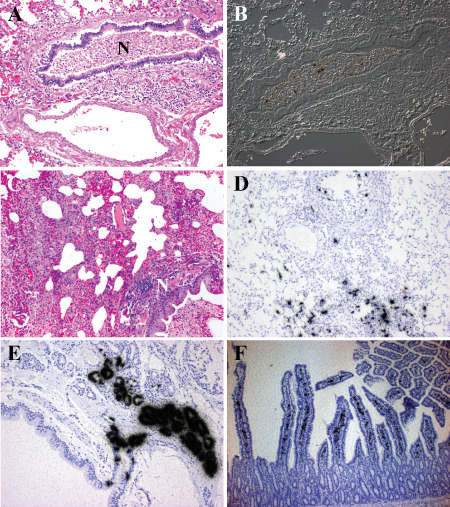

Figure 2.

H1N1 virus infection of human and ferret. A,B. Histopathology of the lung from a patient who succumbed to H1N1pdm09 virus infection. A. Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E)‐stained paraffin section demonstrates a severe bronchopneumonia. Necrotic debris (N) fills the lumen of a moderate size bronchiole. Surrounding alveolar tissue shows edema and severe inflammation. B. Differential interference contrast and in situ hybridization for influenza matrix protein RNA (black grains) demonstrates infected cells within the necrotic debris. At this late stage of infection, the immune response has cleared the majority of virus. C–E. Histopathology of lungs from ferrets inoculated with H1N1 virus intranasally. C. H&E‐stained paraffin section illustrates the severe bronchopneumonia at 5 days post‐infection (DPI). Necrotic debris (N) fills the lumen of a moderate size bronchiole. Surrounding alveolar tissue shows edema and severe inflammation. D. In situ hybridization for influenza matrix protein RNA (black grains) (counterstained with hematoxylin) shows infected cells in epithelial cells of the bronchi and alveoli at 3 DPI. More viruses are detected in the ferret lung suggesting the animal was sacrificed at an earlier stage of infection than when the human case died. By 8 DPI, no virus is detected in the ferret lung. E. In situ hybridization for influenza matrix protein RNA (black grains) (counterstained with hematoxylin) illustrates the severity of submucosal gland involvement as early as 1 DPI. F. The histopathology of small bowel from a ferret infected with H1N1 virus 14 days previously. In situ hybridization for influenza matrix protein RNA (black grains) (counterstained with hematoxylin) demonstrates infected cells within the lamina propria at a time when virus cannot be detected anywhere else systemically.