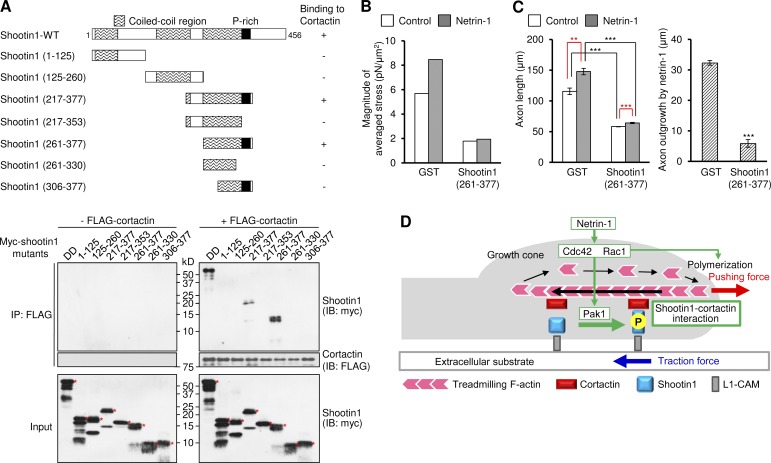

Figure 7.

Shootin1–cortactin interaction mediates netrin-1–induced generation of traction force and axon outgrowth. (A, top) Schematic representation of WT and shootin1 deletion mutants, and their abilities to interact with cortactin. (A, bottom) In vitro binding assay using purified myc-tagged shootin1 mutants and purified FLAG-cortactin. Myc-shootin1 mutants (80 nM) were incubated with FLAG-cortactin (80 nM) and anti-FLAG antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-myc or anti-FLAG antibody. Asterisks denote myc-tagged shootin1 mutants. (B) Statistical analyses of the magnitude of the traction forces under axonal growth cones overexpressing myc-GST or myc-NES-shootin1 (261–377) before or after netrin-1 stimulation. n = 19 growth cones. (C) 3 h after plating, hippocampal neurons overexpressing myc-GST or myc-NES-shootin1 (261–377) were incubated with BSA (control) or 300 ng/ml netrin-1 for 40 h. The graph shows axon length. A total of 544 neurons were examined in three independent experiments. (D) A model for signal–force transduction in axon outgrowth. Netrin-1 induces Pak1-mediated shootin1 phosphorylation, which in turn promotes the interaction between shootin1 and cortactin. The shootin1–cortactin interaction couples F-actin retrograde flow with cell adhesion, thereby transmitting the force of F-actin retrograde flow (black arrow) onto the extracellular substrate (blue arrow). This also reduces the speed of the F-actin flow, thereby converting actin polymerization into force that pushes the leading edge membrane (red arrow). F-actin adhesion coupling and actin polymerization, under the activation of Cdc42 and Rac1, cooperate complementarily for efficient promotion of protrusive forces. Data represent means ± SEM (error bars); ***, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; ns, nonsignificant.