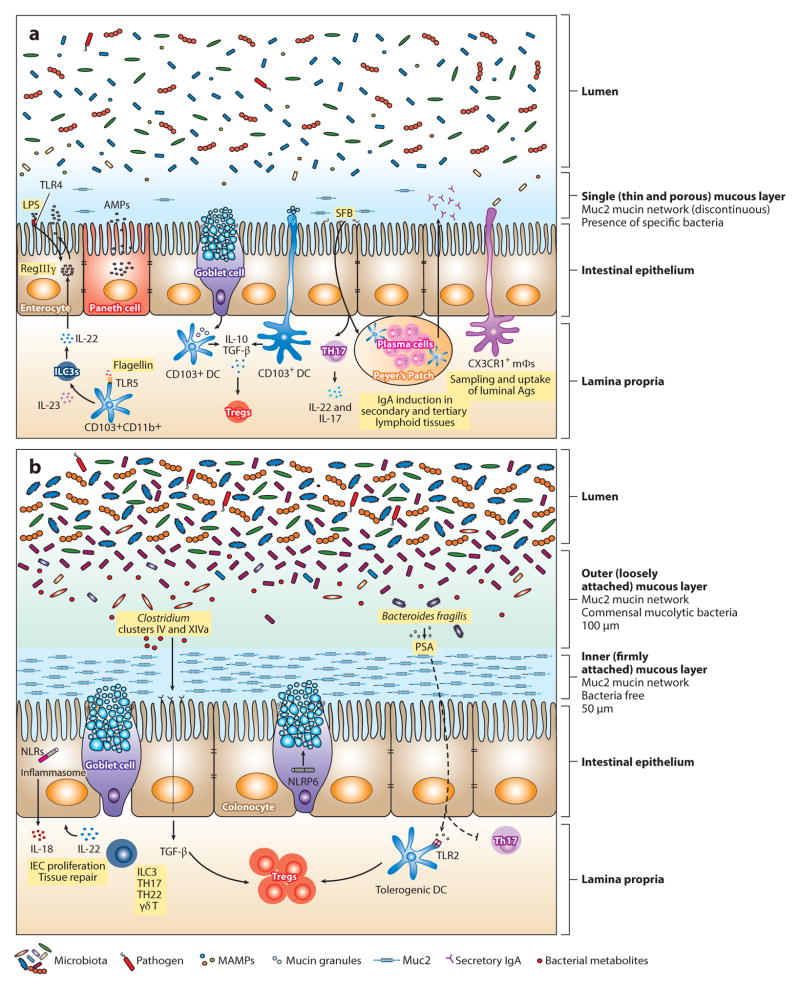

Figure 1.

Maintenance of intestinal homeostasis in the gastrointestinal tract. The intestinal epithelial surface is coated with a layer of mucus that has a pivotal role in intestinal barrier function. This mucous layer is organized by Muc2 mucin glycoproteins that polymerize into a gel-like structure, preventing luminal bacteria from coming into contact with epithelial cells. (b) In the large intestine, two mucous layers protect the colonic epithelium: a bacteria-free, dense, inner layer followed by an outer layer that harbors mucus-degrading bacteria. (a) In contrast, a single, loosely attached layer of mucus lines the small intestine. Mucins are produced by goblet cells and stored in secretory granules until appropriate stimulation, such as signaling through the Nod-like receptor pyrin domain 6 (NLRP6) inflammasome, prompts their release. Consistent with abundant mucus production in the colon, the number of goblet cells is much greater in the large intestine compared with the small bowel. The density and composition of luminal bacteria also differ between these two compartments. The small intestine harbors ~108 bacteria per gram of content. In mice, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) adhere to the intestinal surface and enhance the development of Th17 cells and the production of IgA by B cells. Microbial molecules stimulate the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from epithelial and Paneth cells through activation of innate immune receptors. For example, induction of regenerating islet-derived 3 γ(RegIIIγ), an antimicrobial protein that targets gram-positive bacteria and maintains host-bacterial segregation, is mediated through lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagellin stimulation of TLR4+ (Toll-like receptor 4) radioresistant cells and TLR5+CD103+CD11b+ dendritic cells (DCs), respectively. DCs and macrophages sample luminal antigens and stimulate cytokine production and T cell differentiation. Although CX3CR1+ macrophages are the major antigen-sampling mononuclear phagocytes in the small intestine, CD103+ DCs play a role as well. Nearly 1011–1012 bacteria reside in the large intestine. The microbiota are diverse, mainly comprising Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroides, and Clostridium groups IV and XIV. Tissue repair and tolerance to commensal and food antigens are key factors for maintaining homeostasis in the gut. IL-22 promotes epithelial cell proliferation and repair; however, excessive and aberrant signaling can lead to inflammation and colitis. Tolerance is accomplished by the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) through several mechanisms. In the small intestine, CD103+ DCs take up mucus and stimulate Tregs through IL-10 and TGF-β. Although the mechanism has not been elucidated, it is possible that DCs take up mucus directly by extending dendrites into the lumen or that goblet cells transfer mucus to DCs, as has been shown with antigen. In the colon, specific Treg-inducing bacteria have been identified. For instance, Clostridia spp. generate metabolites that upon receptor binding stimulate the production of TGF-βby epithelial cells. Polysaccharide A (PSA) from Bacteroides fragilis enhances Treg function (either through direct stimulation of TLR2+ Tregs or through a TLR2+ DC intermediate) while inhibiting proinflammatory Th17 responses. Abbreviations: ILC3, type 3 innate lymphoid cell; MAMPs, microbe-associated molecular patterns; mΦ, macrophage.