Abstract

Tinea capitis is a scalp infection caused by fungi. In Brazil, the main causative agents are Microsporum canis and the Trichophyton tonsurans. Etiological diagnosis is based on suggestive clinical findings and confirmation depends on the fungus growth in culture. However, it is not always possible to perform this test due to lack of availability. We reveal the dermoscopic findings that enable distinction between the main causative agents of Tinea capitis, M. canis and T. tonsurans. The association of clinical and dermatoscopic findings in suspected Tinea capitis cases may help with the differential diagnosis of the etiological agent, making feasible the precocious, specific treatment.

Keywords: Dermoscopy, Infection, Tinea capitis

INTRODUCTION

Tinea capitis (TC) is a dermatophyte fungi infection of the scalp that occurs mainly in children. The infection is transmitted by direct contact with infected people or indirectly through contaminated objects such as combs, brushes and stuffed animals.1,2,3

Microsporum canis is the most common pathogen of TC in Brazil.2 Usual sources of infection by M. canis are infected cats. In the United States, there have been recent reports of a dramatic increase in infections by Trichophyton tonsurans.2,4,5

Invasion of the hair shaft occurs by ecthotrix or endothrix infection. In ecthotrix parasitism, fungal infection is due to arthroconidia (spores) that adhere to the hair shaft surface. In endotrix, the pathogen invades the hair shaft without destroying its cuticle. M. canis infection usually causes ecthotrix parasitism, whereas endothrix is caused by T. tonsurans.1,3,5

The clinical features of TC vary considerably, although in most cases, they do not allow the correct identification of the pathogen. TC caused by M. canis may present itself as a non-inflammatory, circumscribed, annular plaque on the scalp, which can be covered by gray scales. This plaque occurs as a result of hair breakage just above the skin's surface, producing tonsured areas. Lesions vary in size and can be single or multiple. Nevertheless, TC caused by T. tonsurans often provokes an inflammatory reaction, forming large, irregular and scaly plaques with broken hair.1,2,5,6,7

Clinical diagnosis of TC is confirmed by fungus visualization through direct mycological exam or growth of the specific fungus in a suitable culture environment. In the direct mycological exam, hyphae and spores are displayed. However, they cannot be reliably used for identifying the species that causes TC. They may occasionally allow the distinction between ecthotrix and endotrix invasion of the hair. Definitive identification of the pathogen species is carried out by fungal culture and growth occurs after 3-4 weeks in most cases, representing an important delay in diagnosis.1,2,4,5,8

The usefulness of dermoscopy as a supplementary method for examining hair and scalp disorders is well-documented for several conditions and it is a non-invasive, quick and inexpensive procedure. 6 It was recently described as an auxiliary method to TC diagnosis.6,7,9,10 The aim of this study is to identify dermoscopic changes that enable distinction between TC caused by M. canis and TC brought about by T. tonsurans.

CASE REPORT

We describe six TC patients, four with TC by M. canis and two by T. tonsurans, who were mycologically confirmed through direct exam with potassium hydroxide 20% and specific fungal growth in a suitable culture environment.

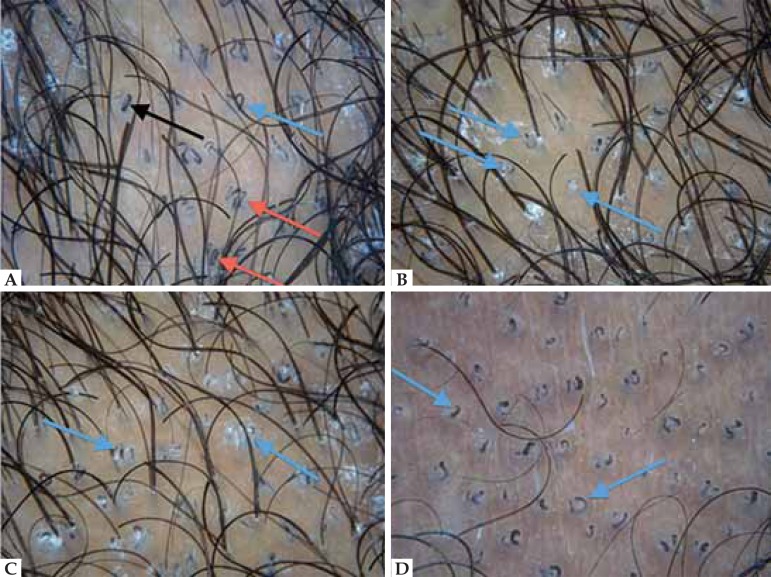

Dermoscopy exam was performed before the beginning of treatment (DermLite II PRO HR, 3Gen, California, USA, x10). The images were photographed and analyzed later. Dermoscopy of the scalp and hair shaft of the four patients with TC due to M. canis showed dystrophic and «elbow-shaped» hairs, in addition to different height levels of broken hair; most of them broke above the follicular ostia at heights of about 2-3 mm (Figure 1). Elbow-shaped hair was pre-tonsured and scales were white, shiny and well-adhered to the hair shaft. Comma-shaped hairs were observed in low numbers and only in one of the four patients with TC by M. canis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Dermoscopic alterations in TC by M. canis: A- Dystrophic, "elbow" (pre-tonsured/ black arrow) and numerous tonsured hairs; shiny scales well-adhered to the shafts. B - "Corkscrew" hair (black arrow), tonsured at different height levels but mostly at points situated further from the follicular ostia (blue arrow); scales adhered to the shafts. C - Few strands of hair in "comma" and "question mark" shapes (black arrow) (DermLite II PRO HR, 3Gen, California, USA, x10).

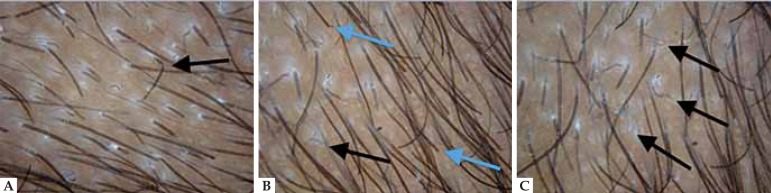

The two patients with TC caused by T. tonsurans showed multiple comma-shaped hairs, as well as hair shaped like a clip or question mark: comma-shaped modified hair. These «tonsured hairs» were found in large amounts closer to the follicular ostia (Figure 2). The scales were more concentrated in the periphery of the plaque.

FIGURE 2.

Tinea capitis. Dermoscopic alterations in tinea capitis by Trichophyton tonsurans: A - Large amount of "comma-"(black arrow), "clip-" (red arrow) and "question mark-" (blue arrow) shaped hair, and scales around the lesion. B - Homogeneous tonsure in high quantity and closer to the scalp (blue arrow). C - Broken hair near the scalp (blue arrow). D - Commashaped hair in large amounts, and various tonsured strands closer to the follicular ostia (blue arrow) (DermLite II PRO HR, 3Gen, California, USA, x10)

DISCUSSION

TC is the most common childhood dermatophytosis with an increasing incidence worldwide. Although uncommon after puberty, it is important to remember that TC can affect adults.1,2,4,5 The main causative agents are Microsporum canis and Trichophyton tonsurans.1,2,4 Usually, these agents infect the hair shaft through different pathways.1,2

In TC caused by M. canis, ecthotrix parasitism is predominant. Hair strands break at higher levels, further from the follicular ostia, and this "tonsure" occurs in small amounts. On the other hand, in infection caused by T. tonsurans, where parasitism is predominantly endotrix, strands are full of hyphae, leading to a larger number of broken hairs near the follicular ostia. In these cases, comma-shaped hair and its variations are present in greater quantity.

In 2008, Slowinska et al.7 published the first paper revealing dermoscopic findings in TC. The authors compared dermoscopic findings with those present in alopecia areata, which they regarded as the main differential diagnosis for TC. They concluded that the comma-shape hair strands may be dermoscopic markers for TC, which do not appear in alopecia areata.10

Another study was published by Sandoval et al. 10 in 2010, in which all seven patients presented comma-shaped hair: two with infection by T. tonsurans and five by M. canis. Nonetheless, no dermoscopic differences between them were detected.

The present report is the first to outline distinct characteristics between TC caused by M. canis or T. tonsurans. Furthermore, the authors propose a new dermoscopic approach. The importance of the etiological distinction is relevant in TC treatment. As in the case of infection caused by M. canis, higher doses of available antifungal agents and/or longer duration of treatment may be necessary.1

The association of the clinical and dermatoscopic findings in suspected TC cases may help with the differential diagnosis of the etiological agent. This method is practical and easy to perform. Dermoscopy in this context still has limitations in comparison with direct mycological exam and fungal culture, which are the gold standard, but these lack availability in some regions of Brazil. Such limitations are attributable to the fact that statistical formulations cannot be inferred from the sample obtained. Future studies with a larger number of patients are desirable.

Footnotes

Financial Support: None.

How to cite this article: Schechtman RC, Silva NDV, Quaresma MV, Bernardes-Filho F, Bernardes-Filho F, Buçard AM, Sodré CT. Dermatoscopic fi ndings as a complementary tool on the differential diagnosis of the etiological agent of tinea capitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3 Suppl 1):S13-5.

Work performed at the Instituto de Dermatologia Professor Rubem David Azulay - Santa Casa de Misericórdia do Rio de Janeiro - Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil.

References

- 1.Dias MF, Quaresma-Santos MV, Bernardes-Filho F, Amorim AG, Schechtman RC, Azulay DR. Update on therapy for superficial mycoses: review article part I. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:764–774. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gürtler TGR, Diniz LM, Nicchio L. Tinea capitis micro-epidemic by Microsporum canis in a day care center of Vitória - Espírito Santo (Brazil) An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes NC, Akiti T, Barreiros MG. Dermatophytoses in children: study of 137 cases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001;43:83–85. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652001000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Tinea capitis: still an unsolved problem? Mycoses. 2011;54:183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudnicka L, Szepietowski JC, Slowinska M, Lukomska M, Maj M, Pinheiro AMC. Tinea capitis. In: Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, editors. Atlas of trichoscopy Dermoscopy in hair and scalp disease. London: Springer; 2012. pp. 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Rakowska A, Sicinska J, et al. Comma hairs: a dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: a rapid diagnostic method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:S77–S79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kefalidou S, Odia S, Gruseck E, Schmidt T, Ring J, Abeck D. Wood's light in Microsporum canis positive patients. Mycoses. 1997;40:461–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinheiro AM, Lobato LA, Varella TC. Dermoscopy findings in tinea capitis. Case report and literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:313–314. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandoval AB, Ortiz JA, Rodríguez JM, Vargas AG, Quintero DG. Dermoscopic pattern in tinea capitis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:151–152. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]