Abstract

The American Geriatrics Society, with support from the National Institute on Aging and the John A. Hartford Foundation, held its fifth Bedside-to-Bench research conference, “Idiopathic Fatigue and Aging,” to provide participants with opportunities to learn about cutting-edge research developments, draft recommendations for future research, and network with colleagues and leaders in the field.

Fatigue is a symptom that older persons, especially by those with chronic diseases, frequently experience. Definitions and prevalence of fatigue may vary across studies, across diseases, and even between investigators and patients. The focus of this review is on physical fatigue, recognizing that there are other related domains of fatigue (such as cognitive fatigue).

Many definitions of fatigue involve a sensation of “low” energy, suggesting that fatigue could be a disorder of energy balance. Poor energy utilization efficiency has not been considered in previous studies but is likely to be one of the most important determinants of fatigue in older individuals. Relationships between activity level, capacity for activity, a tolerable rate of activity, and a tolerable fatigue threshold or ceiling underlie a notion of fatiguability. Mechanisms probably contributing to fatigue in older adults include decline in mitochondrial function, alterations in brain neurotransmitters, oxidative stress, and inflammation. The relationships between muscle function and fatigue are complex. A number of diseases (such as cancer) are known to cause fatigue and may serve as models for how underlying impaired physiological processes contribute to fatigue, particularly those in which energy utilization may be an important factor. A further understanding of fatigue will require two key strategies: to develop and refine fatigue definitions and measurement tools and to explore underlying mechanisms using animal and human models.

Keywords: fatigue, energy utilization, mitochondria, muscle

The American Geriatrics Society, with support from the National Institute on Aging and the John A. Hartford Foundation, held its fifth Bedside-to-Bench research conference, “Idiopathic Fatigue and Aging,” to provide participants with opportunities to learn about cutting-edge research developments, draft recommendations for future research, and network with colleagues and leaders in the field. The purpose of this article is to report on the highlights of this conference. With the intention of maintaining focus, the discussion was limited to “perception of physical fatigue” and “fatigability” that occurs as a result of physical activity that requires voluntary muscle action and contributes to the decline of physical activity in older persons. The working group recognized that, even within these limits, the origin of fatigue remains multifactorial and that different domains of fatigue overlap and cannot be easily dissected.

OVERVIEW

Fatigue is a common complaint among older persons, especially in those with chronic diseases. As a self-reported measure, fatigue is complex and multidimensional and, not surprisingly, has been defined in a number of ways: as a feeling that interferes with usual functioning and has a multifactorial origin,1 as a sense of diminished energy and increased need to rest,2 and as physical or mental weariness resulting from exertion. As such, definitions of fatigue frequently vary across studies, across diseases, and even between investigators and patients. Performance-based definitions of fatigue have also been proposed, such as the inability to continue exercise at the same intensity that, if ignored, leads to deterioration in performance.3 The prevalence of fatigue in adults varies widely across published studies, from 5% to almost 50%. Some studies report slightly greater fatigue in older adults than younger subjects,4 whereas other surveys find unchanged5 or decreasing fatigue6 with advancing age. Women report fatigue up to twice as often as men, and the diurnal patterns of fatigue in older women differ from those in younger women.7 These disparities may relate to usual levels of physical activity or exertion, beause older individuals may regulate their activity to maintain perceived fatigue levels within a tolerable range. Furthermore, because older people tend to reduce their physical activity, the reference exercise intensity for fatigue might be different in different age groups. Thus, self-reported fatigue alone might not vary considerably across the lifespan, but self-reported fatigue as a function of activity level probably does.

ENERGY UTILIZATION AND FATIGUE

Many definitions of fatigue involve a sensation of “low” energy, suggesting that fatigue could be a disorder of energy balance. Studies have shown8 that 60% to 70% of all energy consumed by an individual over 24 hours is spent on the resting metabolic rate (RMR) or the energy required to maintain life at rest. RMR is high in the first years of life and declines slowly and progressively with aging, on average, primarily because of changes in body composition, but RMR may be higher in some older individuals because of the extra energy required to maintain homeostasis disrupted by age-associated disease. Recent data suggest that an RMR higher than that predicted for age, sex, lean body mass, level of physical activity, or major morbidity is associated with excess mortality.9

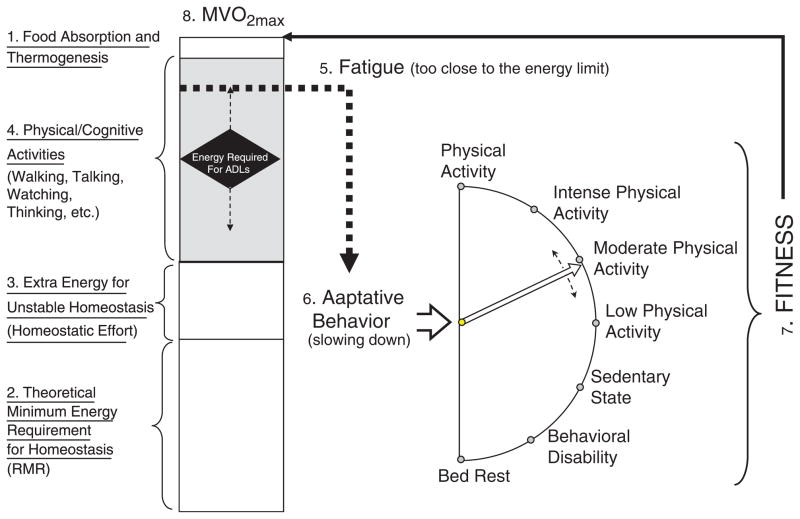

In a model of finite energy availability (Figure 1), the sum of energy required for RMR, homeostatic effort, and thermogenesis leaves a certain amount of energy available for physical and cognitive activity. Perhaps individuals experience fatigue when their energy consumption reaches or surpasses this limit, and the proximity to energetic limits depends on relationships between maximum aerobic capacity, the maximum amount of energy theoretically available, RMR, and energy utilization efficiency, defined as the inverse of the metabolic cost of a standard motor task. Studies of obesity, caloric restriction, and physical activity could thus be interpreted in light of their effects on RMR, energy use efficiency, and aerobic capacity to ultimately understand their effects on the threshold for fatigue. Poor energy utilization efficiency has received little consideration in previous studies but is likely to be one of the important determinants of fatigue in older individuals.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mechanisms for physical fatigue. The box in the left of the figure represents the total amount of energy potentially used by an individual within 24 hours. The size of the box is a measure of fitness and is estimated according to maximum oxygen uptake (MVO2) during a maximal treadmill test. Total energy can be partitioned into portions that serve different purposes. At the top1 is the small amount of energy necessary to process food during digestion and to avoid excessive fluctuation in body temperature. At the bottom2 is the theoretical minimum energy requirement for homeostasis at rest or resting metabolic rate (RMR). The RMR represents 40% to 65% of the total energy used daily and tends to be lower in women, in individuals with less lean body mass, and in older persons. In the presence of pathology and physiological dysregulation, an extra portion of energy is required to maintain homeostatic equilibrium, homeostatic effort,3 or extra energy for unstable homeostasis. The remainder in the middle of the box shaded in gray is the energy used daily for physical and cognitive activities.4 In young and healthy individuals, there is abundant energy left to perform activities of daily living and much more for other activities. In older individuals, because of the reduction in fitness (the whole box is smaller), the extra energy necessary for homeostasis, and the reduction in biomechanical efficiency, additional energy is required to perform the same task, as indicated by the position of the diamond in the middle box. Thus, in some older individuals, performance of basic daily activities may require near maximum energy available. This condition is perceived by the brain as an “alarm” (energy is becoming scarce) and generates “fatigue.”5 The adaptive behavior6 to fatigue is a reduction of physical activity (an attempt to slow down the body and spare energy), which in turn leads to a reduction in fitness,7 further reducing the total energy available and then generating more-severe fatigue, in a vicious cycle. Major challenges to the operationalization of this model are the development of noninvasive methods for measuring MVO2 in 24 hours and the additional portion of energy required to balance homeostatic dysregulation.

This hypothetical model is consistent with the idea of “fatigability,” a phenotype describing the change in fatigue level as a function of the change in intensity, duration, or frequency of activity. Relationships between activity level, capacity for activity, a tolerable rate of activity, and a tolerable fatigue threshold or ceiling underlie the concept of fatigability. Greater fatigability might then determine functional status by setting a lower activity limit aimed at maintaining the feeling of fatigue within a tolerable range. In this way, fatigue then becomes a major determinant of sedentary behavior. It could be postulated that interventions that target fatigue by increasing energy availability may also help reduce sedentary behavior and disability.

A number of factors affect RMR and energy utilization but have not clearly been linked to fatigue, although thyroid disorders, which are highly prevalent in older adults and often characterized partly by fatigue,10 are associated with changes in energy expenditure, lipid oxidation, and glucose metabolism. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a role for thyroid homeostasis in modulating lipid, carbohydrate, and energy metabolism in healthy individuals,10–13 and thyroid hormone appears to play a significant role in regulating RMR and aerobic capacity. Fatigue characterizes both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism in older people.14

MITOCHONDRIA AND FATIGUE

Because mitochondria are the energetic machines of all animal cells, it is conceivable that mitochondrial function is important in causing fatigue. Evidence suggests that the number and function of mitochondria decline15 and that susceptibility to mutation and damage from reactive oxygen species (ROSs) increases with age. In younger organisms, low mitochondrial content and function have been associated with metabolic abnormalities common to aging, such as obesity, impaired lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.15–18 Aerobic exercise increases mitochondrial content in older people, although not to levels seen in younger, healthy adults, and this increase in content is associated with higher mitochondrial capacity for electron flow and transport.19 Caloric restriction in young nonobese people decreases ROS production20 and increases mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (mtDNA) content and insulin sensitivity,21,22 but it does not increase critical mitochondrial enzyme activities in skeletal muscle. The effects of combining exercise and caloric restriction are not clear. The combination improves insulin sensitivity in middle-aged obese adults, but no further increases in mtDNA content have been observed.21

Many of the proteins in the mitochondria are encoded in the nucleus, leaving only 13 proteins (subunits) encoded by mtDNA. These are critical subunits and represent important regulators of the efficiency by which the chemical energy provided by carbohydrate and lipid metabolism is translated into adenosine triphosphate and heat. Ancient adaptive polymorphisms and recent deleterious mtDNA mutations are among many factors related to changes in energy metabolism. In addition, mtDNA has a high mutation rate because of its exposure to the ROSs produced by inhibited electron flow through the transport chain, and the accumulation of oxygen damage over time leads to a higher ratio of mutant to normal mtDNA. Because this ratio varies from cell to cell, each tissue contains a gradient of mitochondrial dysfunction and biochemical energetic effects, and even a small reduction in mitochondrial function can have a clinical effect.

In diseases in which the mutated mtDNA make up a large proportion of the total mitochondria, fatigability, exercise intolerance,23 cancer, and a wide array of neurological, cognitive, and metabolic disorders are seen. For example, a case report of a patient carrying a homozygous deletion of the mitochondrial ANT1 gene described mtDNA degeneration, chronic muscle weakness, childhood fatigability, and muscle pain.24 Similarly, an ANT1-knockout mouse model exhibited fatigue and exercise intolerance,25 with carbon dioxide production limiting maximum aerobic capacity almost immediately upon the initiation of exertion. This mouse model also showed upregulation of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation and antioxidant defenses and downregulation of those involved in glycolysis. Another mouse model, which expressed a missense mutation in the mitochondrial cytochrome c-oxidase gene, exhibits abnormal mitochondria, cardiomyopathy, and 50% lower cytochrome oxidase production.26 It has been postulated that mitochondrial DNA becomes vulnerable in older individuals because of the high rate of accumulation of mutations.

MUSCLE FUNCTION AND FATIGUE

The relationships between neuromuscular function and physical fatigue as defined here are not known. Muscle changes with age, both anatomically (e.g., smaller size, type I and type II fiber area, and number of motor units; greater fat content) and functionally (lower strength, power, and maximum motor unit discharge rate; slower contractile properties; and greater oxidative energy utilization). An important functional characteristic of muscle is its ability to resist fatigue, defined as the inability to maintain force or power as a result of prolonged or repetitive muscular activity. There is evidence that changes in the aged muscular system contribute to differences in muscle fatigue resistance in young and old adults under a range of conditions. Because the degree and mechanisms of muscle fatigue can vary depending on the contraction task or the muscle studied, age-related changes in the neuromuscular system may have a variable effect on fatigue outcomes.

Some earlier studies have suggested that older muscles may be as or more fatigable than younger muscles during repetitive motor tasks, although more-recent studies suggest that muscle in older adults may be more resistant to fatigue than in young adults, particularly during isometric contractions.27 In one study, young adults were quicker to fatigue than older adults for 20% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) isometric elbow flexion force, but young and old had a similar duration for 80% MVC.28 In other studies, participants aged 60 to 85 experienced less fatigue after maximal isometric ankle contractions,29,30 including under ischemic and nonischemic conditions,31,32 than did young adult participants. Neural and muscular factors might form a metabolic basis for this fatigue resistance.33 Older adults showed significantly lower peak glycolytic rates,31 less accumulation of inorganic phosphate, and less intracellular acidosis than did younger adults,29,31 and under ischemic conditions, central activation failure (defined as the condition under which a muscle can be electrically stimulated and produce greater force) was less pronounced in older than younger adults.32 In contrast to studies of fatigue using isometric contractions, dynamic contractions, which rely on velocity and power generation, can result in relatively more fatigue in older adults.34,35 Another factor to consider is that, in absolute terms, older individuals often work at lower levels than young adult participants. Although a full treatment of this complex topic is beyond the scope of this article, the mixed results on fatigue resistance in old age probably arise in part from task-specific variations in the stresses placed on the neuromuscular system. Furthermore, the role of muscle fatigue in the overall fatiguability of old age remains an open question.

Given these muscle metabolic and functional findings with age, fatigue reduction in older adults may follow a number of different related paths. Ergoreceptors are metabo- and mechanoreceptor-afferent fibers originating in skeletal muscle. Modulation of the activation of ergoreceptors, related to work,36 may be potential targets to lessen fatigue. adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is sensitive to intracellular energy charge and can increase energy stores by stimulating transport of fatty acid chains across mitochondrial membranes, facilitating glucose uptake, and inhibiting glycogenesis, is another potential target.37,38 Activation of AMPK inhibits muscle protein synthesis, because AMPK activation is thought to occur during low energy states to promote energy conservation; as such, long-term AMPK activation may have maladaptive effects on muscle integrity. Mice deficient in either subunit of AMPK show normal contraction-stimulated glucose uptake and force production, but mice deficient in the α2 subunit of AMPK show disturbed muscle energy balance, and those deficient in both subunits show poorer glucose uptake.

CENTRAL UNDERLYING PROCESSES FOR FATIGUE

As mentioned above, fatigue may be conceptualized as a signal that alerts the brain that a certain level of activity “cannot be sustained.” A number of factors can amplify and reduce the signal so that the perception of fatigue is modulated. The factors that can potentially modulate the perception of fatigue are not completely known but may include neurotransmitters deregulation, inflammation, oxidative stress (ROSs), and many others.

Neurobiology of Fatigue

The Central Fatigue Hypothesis39 assumes that exercise increases serotonin production in the brain, which in turn augments lethargy and loss of drive, resulting in reduced motor unit recruitment and ultimately in poorer physical and mental efficiency. Studies in rats also suggest a role for dopamine in the drive to continue exercise despite fatigue. Several candidate neurotransmitters have been manipulated in human studies, but no consistent effects on exercise performance have been observed.40–44

Thermoregulation might play a role in the neurobiology of fatigue. In studies of trained cyclists, time to exhaustion declined at higher temperatures,45,46 and the rate of perceived exertion increased with increasing core temperature.47 Participants given bupropion or methylphenidate performed longer and faster at higher temperatures, suggesting a role for dopaminergic pathways in postponing fatigue at these temperatures.48–50 These results were consistent with animal studies in which amphetamine injection before exercise improved performance at higher temperatures but induced abnormalities in thermoregulation.51,52

Oxidative Stress

ROSs produced by exercise facilitate myofilament contractions and the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, both in a biphasic manner.53,54 ROSs also target some metabolic enzymes55 and signal transduction pathways,56 yet the role for ROSs in fatigue is complicated, because ROS production and mechanisms of fatigue vary according to tissue or muscle type.57 More study is needed to examine this heterogeneity, the cellular sources of ROSs, and how these factors differ with age.

Inflammation

Work in breast cancer survivors and animal models has correlated fatigue with biomarkers of inflammation, such as interleukin (IL)-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6.58,59 Human and animal studies suggest a cycle in which peripheral inflammation activates brain cytokine production, resulting in sickness behavior. Intense or prolonged activation of the immune system induces depression in vulnerable individuals. Fatigue is an important neurovegetative component of inflammation-associated depression. Because aging involves inflammation, older individuals are at higher risk for developing symptoms of depression and fatigue. More research is needed to clarify the intermediate mechanisms linking inflammation and fatigue (e.g., balance between proinflammatory and inflammatory cytokines) and to determine whether fatigue is part of a larger syndrome that includes other nonspecific symptoms of inflammation.

DISEASE-BASED MODELS OF FATIGUE

A number of diseases are known to cause fatigue and may serve as models for how underlying impaired physiological processes contribute to fatigue, particularly those in which energy utilization may be an important factor, but the link between these underlying mechanisms and self-reported or performance-based fatigue has not necessarily been clarified in each disease model below. A number of relevant disease models are also not represented here, notably neurodegenerative disease (e.g., multiple sclerosis) and rheumatological diseases (e.g., fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome).

Cancer

Studies in cancer patients have yielded the most information about self-reported fatigue and may be considered the prototype for disease-induced fatigue. Most of these studies have focused on treatment-related fatigue, which generally follows the same trajectory regardless of type of treatment. Cluster analysis has linked fatigue with complaints of weakness, inability to perform routine tasks, sleepiness and drowsiness, lack of appetite, and possibly pain and disturbed sleep.60 Studies of pharmacological interventions against cancer-related fatigue have yielded mixed results,61 and a meta-analysis has found limited evidence that non-pharmacological interventions are useful.62

Congestive Heart Failure

Decrements in muscle function in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), when compared with age-matched controls, provide a possible physiological basis for fatigue in CHF. Magnetic resonance imaging and muscle biopsies reveal fat and fibrous tissue replacing muscle, type I and II fiber atrophy, low levels of oxidative enzymes, low mitochondrial volume, and changes in mitochondrial architecture in the muscles of patients with CHF.63 These changes have also been associated with declines in peak aerobic capacity. Ergoreceptors, afferents sensitive to muscular work, are hypersensitive in these patients,36 resulting in augmented responses and an exaggerated perception of effort. Exercise-associated elevations in inorganic phosphorus are more pronounced, acidosis is greater, and recovery of phosphocreatine levels is slower in patients with CHF, consistent with impaired oxidative metabolism in patients with CHF.64,65 Slow glycogen release significantly increases submaximal exercise duration in patients with CHF and healthy controls,66 although peak aerobic capacity is not affected. Treatment of anemia with erythropoietin alleviates fatigue and increases hemoglobin levels and peak performance in patients with CHF.67

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Up to 98% of patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) report fatigue affecting their activities of daily living, and the prevalence of fatigue might be even higher in some subgroups, including patients aged 35 and older.68 The etiology of fatigue is complicated in patients with HIV. One-third of these patients are co-infected with hepatitis C, and approximately half have anemia. Opportunistic infections are also associated with fatigue. Concurrent with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), fatigue has been associated with age, genetics, chronic “smoldering” immune activation, and mitochondrial toxicity. The metabolic syndrome has become increasingly common in patients receiving HAART, primarily because of insulin resistance arising from factors such as lipodystrophy,69 and drug-specific effects on mitochondria, energy production and metabolism, and lipogenic pathways cause lipodystrophy in part.70–73

Sleep Disorders

Sixty percent of older adults complain about sleep disorders, including sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, and insomnia. Older age has been associated with less sleep time, poorer sleep efficiency, less slow-wave sleep, difficulty in maintaining sleep; and daytime sleepiness.74 Studies in humans and in animal models have correlated sleep disturbance with metabolic and energetic abnormalities.75,76 Mice with homozygous mutations in the clock gene exhibit abnormal diurnal variations in eating and activity, and they become obese on an ad libitum diet. Short-term sleep deprivation in humans results in signs of insulin resistance and impaired glucose control. Thus, sleep disorders lead to sleepiness through a process that is mediated by and influences appetite, inflammation, insulin resistance, and autonomic function.

MEASUREMENT OF FATIGUE

Self-Report Measures

A number of different questions and validated tools have been developed to assess fatigue, particularly those that are disease specific, but there is no criterion standard. Many of these tools use a multidimensional approach, but scores produced using items rated for intensity differ little from those produced using items rated for frequency.77 Moreover, a few studies suggest that certain items may be considered unidimensional and thus may be more practical for short-form assessments.78

The National Institutes of Health is creating the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a publicly available, adaptable, sustainable system to assess reported outcomes, including fatigue, across a wide range of diseases and conditions. PROMIS will provide reliable and precise measurements of these outcomes, using fewer items than are necessary with traditional assessments.

The link between fatigue and daily activity can be assessed using ecological momentary assessment, experience sampling, and day-reconstruction methods. Fatigue severity scales may be used, but understanding how well certain tasks are tolerated (which tasks induce fatigue that are or are not well tolerated) may provide a better link between fatigue, activity, and ultimately disability. These self-report measures can now be linked to accelerometric measures of daily activity to generate profiles of physical activity and fatigue. Such profiles can be used to assess activity at tolerable fatigue, fatigability with task performance, and ultimately responses to interventions designed to reduce fatigability.

Performance-Based Measures

Performance-based measures of fatigue usually involve measurement of activity and energy expenditure and then monitoring for deterioration of performance. A number of criterion-standard measures of physical activity and energy expenditure measurement may not be applicable. Indirect calorimetry holds the most promise, and whole-room indirect calorimetry chambers, or metabolic chambers, have recently been used in 24-hour studies to measure changes during sleep, rest, and exercise. The use of water doubly labeled with deuterium and oxygen-18 allows the measurement of energy expenditure over longer periods of time, but it lacks details, is expensive and slow, and assumes a static respiratory quotient.

Indirect calorimetry has traditionally been used to estimate aerobic capacity and may provide an important link to estimate fatigability based on oxygen uptake. Age and disease are both associated with declines in aerobic capacity. Peak aerobic capacity measures are used for older adults, because standard measures such as maximum aerobic capacity are difficult to achieve. In a 6-minute sub-maximal walk task, mobility-impaired older adults experience longer initial oxygen deficits and delayed achievement of steady state during exercise and delayed recovery after exercise. Moreover, submaximal oxygen kinetics in mobility-impaired older adults correlate as highly with functional mobility performance as do measurements of peak aerobic capacity,79 and these kinetics might be more useful in light of the submaximal aerobic demands of many activities of daily living. The physiological link between subjective fatigue and objective measures of oxygen utilization is not known.

Accelerometers are now in widespread use to measure physical activity, the most variable component of daily energy expenditure (Figure 1), and they have been used in fatigue and sleep studies. Accelerometers differ in a number of properties, including accuracy, precision, and relative response to activity intensity, and their use needs to be balanced with feasibility and acceptability to the participant.

INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE FATIGUE

Two interventions that were explored at the conference included activity strategy training to reduce fatigue burden and interventions to reduce impairment from sleep disorders. Although exercise is a consistent component of fatigue reduction programs, many exercise programs are not linked to specific daily activities or the environmental context, nor do they reduce individual barriers to physical activity. Recent data suggest that patients with osteoarthritis who participate in group exercise and receive activity strategy training experience less pain and fatigue and greater physical activity than patients who participate in group exercise and receive health education.80 Exercise, more daily activity, bright-light therapy, and cognitive behavior therapy have also been assessed as interventions against fatigue induced by a sleep disturbance,81,82 although many cognitive behavior therapy studies have been conducted in younger people and only recently have begun to include older patients. Pharmacological interventions have also been studied, but no drug has been shown to consistently improve fatigue. Moreover, studies of pharmacological approaches to sleep disturbance have focused mostly on nighttime sleep and not on daytime function.

IDIOPATHIC FATIGUE AND AGING: FUTURE RESEARCH

Two objectives are critical to advancement in research on fatigue: to develop and refine understanding of how fatigue develops during activity and to explore underlying mechanisms that generate and modulate fatigue in animal and human models (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommendations for Future Fatigue Research

| I. Develop and refine understanding of fatigue in relation to activity |

| A. Develop criteria to distinguish between different levels of fatigability (the relationship between fatigue and activity) and their clinical implications |

| B. Develop measures of fatigability relevant to older adults |

| a. Identify maximum physical activity (PA) levels, adjust PA measures according to standardized task-specific PA levels, and determine energy utilization efficiency |

| b. Explore how energy efficiency and activity levels relate to functional disability |

| c. Develop a more-detailed analysis of the fatigue experience to include a description of the fatigue episode, population affected, surrounding milieu in which fatigue occurred, specific task during which the fatigue was encountered, and physical impairment and disability associated with fatigue |

| C. Refine self-reported fatigue measures |

| a. Determine which global or generic terms of disease-specific scales of fatigue are relevant for older adult populations |

| b. Identify the most-appropriate fatigue assessment instruments for particular studies or research questions (e.g., uni- versus multidimensional instruments) |

| c. Assess the relationship between fatigue and other symptoms in specific diseases or conditions |

| d. Improve self-reported measures to ensure validity in large epidemiological studies |

| e. Validate measures with respect to clinical outcomes |

| f. Improve terminology in self-reported measures (e.g., through attention to investigator versus patient language) |

| E. Explore the relationships between, and the limitations and benefits of, self-reported versus relevant objective measures of fatigue |

| F. Improve measures of energy expenditure and physical activity |

| a. Develop methods for measuring resting metabolic rate over extended periods of time |

| b. Compare single versus longitudinal measures, integrate multiple measures, examine variability in parameters over time, and identify the optimal time frame for measuring changes |

| G. Establish relationships between research- and clinical-oriented assessments |

| a. Develop a multilevel consensus battery or algorithm to assess fatigue, including, for example, medical history and physical examination, sleep monitoring, muscle testing, cardiovascular measures, and cytokine levels |

| H. Account for medication usage and intra-individual variations in response to medications during assessment of fatigue |

| II. Explore underlying mechanisms (in human and animal models) |

| A. Alterations in energy production and utilization |

| a. Explore individuals’ ability to switch fuel source (carbohydrate vs fat) in different tissues for energy production and determine the extent to which this ability changes with aging |

| b. Identify changes in the relative contributions to energy production of oxidative phosphorylative, glycolytic, and phosphocreatine pathways during specific activities |

| c. Identify valid cellular or molecular markers of mitochondrial biogenesis, function, and death |

| d. Identify limitations in oxygen availability through changes in respiratory function, oxygen carrying capacity, and delivery |

| e. Quantify at the tissue or organ levels the competition for energy resources between homeostatic processes and volitional expenditures |

| f. Apply metabolomic strategies to identify molecular and cellular pathways associated with fatigue in high-throughput studies |

| B. Effects of inflammation and oxidative stress |

| a. Clarify the intermediate mechanisms linking inflammation and fatigue |

| b. Develop molecular markers of inflammation, such as serum levels of cytokines, glycosylated proteins, and other downstream targets of oxidative stress |

| c. Study links between inflammation and mitochondrial biology (e.g., through effects of induced inflammatory responses on central and peripheral mitochondrial function) |

| C. Central and peripheral nervous system mechanisms |

| a. Elucidate neuronal mechanisms regulating energy production and utilization (e.g., through functional imaging techniques in fatigued and nonfatigued states) |

| b. Determine the role of brain energy expenditure and neurotransmitters in fatigue |

| c. Determine the role of neurogenesis in fatigue |

| d. Determine the relationship between sleep deprivation, brain metabolism, and task performance |

| e. Study the relationship between nerve activity and muscle force |

| D. Develop animal models and subsequent objective measures for muscle fatigue, exercising to exhaustion, spontaneous physical activity, sleep quality, and sleep duration |

| E. Explore relationships between multifactorial causes of fatigue (e.g., through a sequential intervention study) |

| F Conduct fatigue recovery studies in different populations, including younger adults, older adults, patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, and patients with various diseases and conditions |

| G. Bank biological samples for future analyses as new objective measures of fatigue are developed |

Because individuals may have similar levels of fatigue despite varying levels of activity, it may be important to distinguish between different levels of fatigability. Development of measures of fatigability will put fatigue into the context of physical activity and should consider energy utilization as well as aspects of the individual’s impairment, surrounding milieu, and specific requirements of the task during which the fatigue is encountered. Self-reported measures of fatigue must be further refined, with consideration of the importance of scaling, dimensionality, epidemiological and clinical application, and nuance of terminology. The relationship between these self-reported measures and relevant objective measures must be sought. These objective measures, specifically energy utilization and physical activity, should be evaluated longitudinally. Development of a clinical algorithm to assess fatigue and better consideration of medication effects are also important.

Important mechanisms underlying fatigue that deserve further exploration include alterations in energy production, energy utilization, and the regulation of these processes through effects of mitochondrial function, ongoing inflammation, and oxidative stress. Further work is needed in understanding central and peripheral nervous system fatigue mechanisms, specifically in relevant brain regions; energy utilization; neurotransmitters; and ultimate force output at the muscle level. Developing better animal models and subsequent objective measures of muscle fatigue, exercise fatigue, physical activity, and sleep quality and duration are also needed. Finally, causes of fatigue are multifactorial, and these factors can be studied during interventions to reduce fatigue for a better understanding of the dynamics of fatigue.

Acknowledgments

The conference organizers wish to thank the American Geriatrics Society, the National Institute on Aging (R13 grant AG02830), and the John A. Hartford Foundation for their generous support. The coauthors also acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants P30 AG024824 (Alexander), P30 AG024827 (Studenski), K24 AG019675 (Alexander), K07 AG023641 (Studenski), and P20 CA103730 (Studenski), as well as from the Office of Research and Development, Clinical Science and Rehabilitation Research and Development programs of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH, Baltimore, Maryland. For more information on the Bedside-to-Bench Conference on Idiopathic Fatigue and Aging and to view presentations, visit http://www.americangeriatrics.org/research/confseries/2008_ifa.shtml.

Conference speakers: Neil Alexander, University of Michigan; Francisco H. Andrade, University of Kentucky; Zeeshan Butt, Northwestern University; Francesco S. Celi, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Kong Chen, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Charles Cleeland, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; Robert Dantzer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Basil Eldadah, National Institute on Aging; Luigi Ferrucci, National Institute on Aging; Mariana Gerschenson, University of Hawaii at Manoa; Bret Goodpaster, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; Evan Hadley, National Institute on Aging; Jane Kent-Braun, University of Massachusetts; Donna Mancini, Columbia University; Romain Meeusen, Vrije Universiteit Brussel; George Taffet, Baylor College of Medicine; Doug Wallace, University of California, Irvine; Phyllis Zee, Northwestern University.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, or preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions: All of the authors contributed to the review, concept, design, and preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mock V. Fatigue management: Evidence and guidelines for practice. Cancer. 2001;92:1699–1707. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6+<1699::aid-cncr1500>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SA, Berger AM. Cancer-related fatigue: The evidence base for assessment and management. Cancer J. 2006;12:374–387. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans WJ, Lambert CP. Physiological basis of fatigue. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(1 Suppl):S29–S46. doi: 10.1097/phm.0b013e31802ba53c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerdal A, Wahl A, Rustoen T, et al. Fatigue in the general population: A translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Fatigue Severity Scale. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33:123–130. doi: 10.1080/14034940410028406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickie IB, Hooker AW, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Fatigue in selected primary care settings: Sociodemographic and psychiatric correlates. Med J Aust. 1996;164:585–588. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Schwartz JE, et al. Context effects in survey ratings of health, symptoms, and satisfaction. Med Care. 2008;46:662–667. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181789387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA, et al. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The Day Reconstruction Method. Science. 2004;306:1776–1780. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson MM, Morley JE. Invited review: Aging and energy balance. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1728–1736. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00313.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruggiero C, Metter EJ, Melenovsky V, et al. High basal metabolic rate is a risk factor for mortality: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63A:698–706. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.7.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doucet J, Trivalle C, Chassagne P, et al. Does age play a role in clinical presentation of hypothyroidism? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:984–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asvold BO, Vatten LJ, Nilsen TI, et al. The association between TSH within the reference range and serum lipid concentrations in a population-based study. The HUNT Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:181–186. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortega E, Koska J, Pannacciulli N, et al. Free triiodothyronine plasma concentrations are positively associated with insulin secretion in euthyroid individuals. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:217–221. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega E, Pannacciulli N, Bogardus C, et al. Plasma concentrations of free triiodothyronine predict weight change in euthyroid persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:440–445. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trivalle C, Doucet J, Chassagne P, et al. Differences in the signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism in older and younger patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:50–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb05637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: Possible role in insulin resistance. Science. 2003;300:1140–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.1082889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowell BB, Shulman GI. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2005;307:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1104343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley DE, He J, Menshikova EV, et al. Dysfunction of mitochondria in human skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2944–2950. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodpaster BH, He J, Watkins S, et al. Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin resistance: Evidence for a paradox in endurance-trained athletes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5755–5761. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Fairfull L, et al. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial content and function in aging human skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61A:534–540. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bordone L, Guarente L. Calorie restriction, SIRT1 and metabolism: Understanding longevity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:298–305. doi: 10.1038/nrm1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, et al. Calorie restriction increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toledo FG, Watkins S, Kelley DE. Changes induced by physical activity and weight loss in the morphology of intermyofibrillar mitochondria in obese men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3224–3227. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeppesen TD, Quistorff B, Wibrand F, et al. 31P-MRS of skeletal muscle is not a sensitive diagnostic test for mitochondrial myopathy. J Neurol. 2007;254:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmieri L, Alberio S, Pisano I, et al. Complete loss-of-function of the heart/muscle-specific adenine nucleotide translocator is associated with mitochondrial myopathy and cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3079–3088. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham BH, Waymire KG, Cottrell B, et al. A mouse model for mitochondrial myopathy and cardiomyopathy resulting from a deficiency in the heart/muscle isoform of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Nat Genet. 1997;16:226–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan W, Waymire KG, Narula N, et al. A mouse model of mitochondrial disease reveals germline selection against severe mtDNA mutations. Science. 2008;319:958–962. doi: 10.1126/science.1147786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allman BL, Rice CL. Neuromuscular fatigue and aging: Central and peripheral factors. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:785–796. doi: 10.1002/mus.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon T, De-Lap BS, Griffith EE, et al. Age-related muscle fatigue after a low-force fatiguing contraction is explained by central fatigue. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:457–466. doi: 10.1002/mus.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kent-Braun JA, Ng AV, Doyle JW, et al. Human skeletal muscle responses vary with age and gender during fatigue due to incremental isometric exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1813–1823. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00091.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanza IR, Befroy DE, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related changes in ATP-producing pathways in human skeletal muscle in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1736–1744. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00566.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanza IR, Larsen RG, Kent-Braun JA. Effects of old age on human skeletal muscle energetics during fatiguing contractions with and without blood flow. J Physiol. 2007;583:1093–1105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung LH, Callahan DM, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related resistance to skeletal muscle fatigue is preserved during ischemia. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1628–1635. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00320.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russ DW, Towse TF, Wigmore DM, et al. Contrasting influences of age and sex on muscle fatigue. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:234–241. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815bbb93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrella JK, Kim JS, Tuggle SC, et al. Age differences in knee extension power, contractile velocity, and fatigability. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:211–220. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00294.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNeil CJ, Rice CL. Fatigability is increased with age during velocity-dependent contractions of the dorsiflexors. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62A:624–629. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.6.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piepoli M, Clark AL, Volterrani M, et al. Contribution of muscle afferents to the hemodynamic, autonomic, and ventilatory responses to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: Effects of physical training. Circulation. 1996;93:940–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, et al. AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008;134:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgensen SB, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF. Role of AMPK in skeletal muscle metabolic regulation and adaptation in relation to exercise. J Physiol. 2006;574:17–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acworth I, Nicholass J, Morgan B, et al. Effect of sustained exercise on concentrations of plasma aromatic and branched-chain amino acids and brain amines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;137:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piacentini MF, Meeusen R, Buyse L, et al. Hormonal responses during prolonged exercise are influenced by a selective DA/NA reuptake inhibitor. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:129–133. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2002.000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piacentini MF, Clinckers R, Meeusen R, et al. Effect of bupropion on hippocampal neurotransmitters and on peripheral hormonal concentrations in the rat. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:652–656. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01058.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piacentini MF, Clinckers R, Meeusen R, et al. Effects of venlafaxine on extracellular 5-HT, dopamine and noradrenaline in the hippocampus and on peripheral hormone concentrations in the rat in vivo. Life Sci. 2003;73:2433–2442. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piacentini MF, Meeusen R, Buyse L, et al. No effect of a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor on performance in trained cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1189–1193. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meeusen R, Piacentini MF, Van Den ES, et al. Exercise performance is not influenced by a 5-HT reuptake inhibitor. Int J Sports Med. 2001;22:329–336. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parkin JM, Carey MF, Zhao S, et al. Effect of ambient temperature on human skeletal muscle metabolism during fatiguing submaximal exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:902–908. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez-Alonso J. Separate and combined influences of dehydration and hyperthermia on cardiovascular responses to exercise. Int J Sports Med. 1998;19(Suppl 2):S111–S114. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen B, Nybo L. Cerebral changes during exercise in the heat. Sports Med. 2003;33:1–11. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roelands B, Hasegawa H, Watson P, et al. The effects of acute dopamine reuptake inhibition on performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:879–885. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181659c4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roelands B, Goekint M, Heyman E, et al. Acute norepinephrine reuptake inhibition decreases performance in normal and high ambient temperature. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:206–212. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90509.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson P, Hasegawa H, Roelands B, et al. Acute dopamine/noradrenaline re-uptake inhibition enhances human exercise performance in warm, but not temperate conditions. J Physiol. 2005;565:873–883. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasegawa H, Piacentini MF, Sarre S, et al. Influence of brain catecholamines on the development of fatigue in exercising rats in the heat. J Physiol. 2008;586:141–149. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hasegawa H, Ishiwata T, Saito T, et al. Inhibition of the preoptic area and anterior hypothalamus by tetrodotoxin alters thermoregulatory functions in exercising rats. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1458–1462. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00916.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Westerblad H. Contractile response of skeletal muscle to low peroxide concentrations: Myofibrillar calcium sensitivity as a likely target for redox-modulation. FASEB J. 2001;15:309–311. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0507fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, et al. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol. 1998;509(Pt 2):565–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.565bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ziegler DM. Role of reversible oxidation-reduction of enzyme thiols-disulfides in metabolic regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:305–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li YP, Chen Y, Li AS, et al. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates ubiquitin-conjugating activity and expression of genes for specific E2 and E3 proteins in skeletal muscle myotubes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C806–C812. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson EJ, Neufer PD. Type II skeletal myofibers possess unique properties that potentiate mitochondrial H(2)O(2) generation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C844–C851. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue: Links with inflammation in cancer patients and survivors. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laye S, Bluthe RM, Kent S, et al. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy blocks induction of IL-1 beta mRNA in mice brain in response to peripheral LPS. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R1327–R1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.5.R1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: The M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Minton O, Stone P, Richardson A, et al. Drug therapy for the management of cancer related fatigue. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006704. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006704.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological and activity-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Health Psychol. 2007;26:660–667. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancini DM, Walter G, Reichek N, et al. Contribution of skeletal muscle atrophy to exercise intolerance and altered muscle metabolism in heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85:1364–1373. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mancini DM, Wilson JR, Bolinger L, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurement of deoxymyoglobin during exercise in patients with heart failure. Demonstration of abnormal muscle metabolism despite adequate oxygenation. Circulation. 1994;90:500–508. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kao W, Helpern JA, Goldstein S, et al. Abnormalities of skeletal muscle metabolism during nerve stimulation determined by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in severe congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:606–609. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mancini D, Benaminovitz A, Cordisco ME, et al. Slowed glycogen utilization enhances exercise endurance in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1807–1812. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mancini DM, Katz SD, Lang CC, et al. Effect of erythropoietin on exercise capacity in patients with moderate to severe chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:294–299. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044914.42696.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harmon JL, Barroso J, Pence BW, et al. Demographic and illness-related variables associated with HIV-related fatigue. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shikuma CM, Day LJ, Gerschenson M. Insulin resistance in the HIV-infected population: The potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2005;5:255–262. doi: 10.2174/1568005054880163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carr A, Miller J, Law M, et al. A syndrome of lipoatrophy, lactic acidaemia, and liver dysfunction associated with HIV nucleoside analogue therapy: Contribution to protease inhibitor-related lipodystrophy syndrome. AIDS. 2000;14:F25–F32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McComsey GA, Morrow JD. Lipid oxidative markers are significantly increased in lipoatrophy but not in sustained asymptomatic hyperlactatemia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:45–49. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dagan T, Sable C, Bray J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and antiretroviral nucleoside analog toxicities: What is the evidence? Mitochondrion. 2002;1:397–412. doi: 10.1016/s1567-7249(02)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerschenson M, Brinkman K. Mitochondrial dysfunction in AIDS and its treatment. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:763–777. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zee PC, Turek FW. Sleep and health: Everywhere and in both directions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1686–1688. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spiegel K, Leproult R, L’hermite-Baleriaux M, et al. Leptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: Relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5762–5771. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Van CE, Leproult R, Plat L. Age-related changes in slow wave sleep and REM sleep and relationship with growth hormone and cortisol levels in healthy men. JAMA. 2000;284:861–868. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang CH, Cella D, Clarke S, et al. Should symptoms be scaled for intensity, frequency, or both? Palliat Support Care. 2003;1:51–60. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lai JS, Crane PK, Cella D. Factor analysis techniques for assessing sufficient unidimensionality of cancer related fatigue. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1179–1190. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alexander NB, Dengel DR, Olson R, et al. Oxygen uptake (VO2) kinetics and functional mobility performance in impaired older adults. J Gerontol. 2003;58A:734–739. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.8.m734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murphy SL, Strasburg DM, Lyden AK, et al. Effects of activity strategy training on pain and physical activity in older adults with knee or hip osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1480–1487. doi: 10.1002/art.24105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ancoli-Israel S, Martin JL, Kripke DF, et al. Effect of light treatment on sleep and circadian rhythms in demented nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:282–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naylor E, Penev PD, Orbeta L, et al. Daily social and physical activity increases slow-wave sleep and daytime neuropsychological performance in the elderly. Sleep. 2000;23:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]