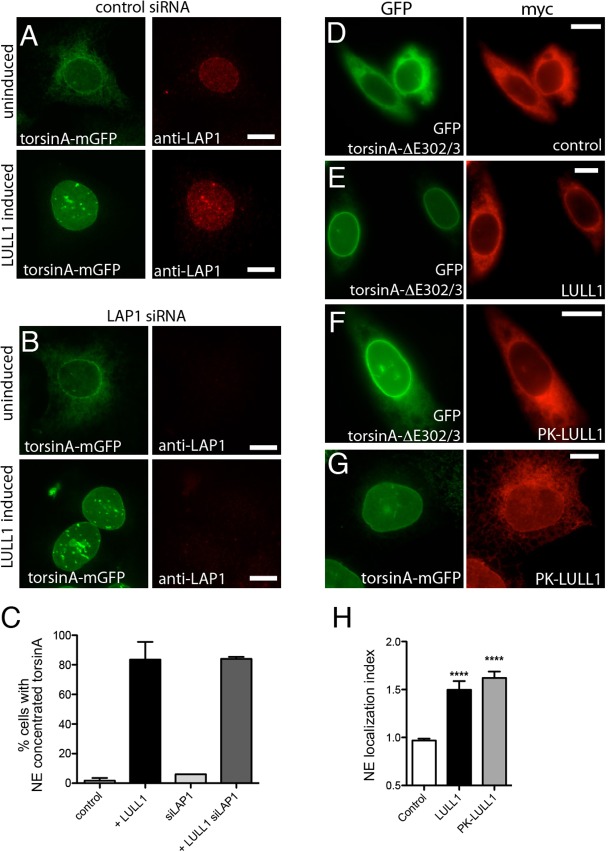

Fig. 3.

LULL1 acts from the ER independently of LAP1 to promote torsinA relocalization. (A,B) U2OS cells stably expressing tetracycline-inducible LULL1–Myc (not imaged) and torsinA–mGFP (left panels) transfected with control (A) or LAP1 siRNA (B). Cells are immunostained to detect endogenous LAP1 (right panels). TorsinA–mGFP is localized throughout the ER under basal conditions (upper panels) but redistributes to the nuclear envelope following increased LULL1 expression (lower panels). LAP1 depletion is seen in (B) and confirmed by immunoblotting (supplementary material Fig. S2D), but does not change LULL1-mediated torsinA relocalization. (C) Quantification of results shown in A and B (mean±s.e.m.; n≥75). (D–F) ER-restricted PK–LULL1 relocalizes torsinA-ΔE302/3 to the nuclear envelope. Images of GFP–torsinA-ΔE302/3 (left panels) in CHO cells co-transfected with (D) control [chicken hepatic lectin transmembrane fused to Myc (Soullam and Worman, 1995)], or (E,F) the indicated Myc–LULL1 fusions (right panels; red). (G) ER-restricted LULL1 relocalizes torsinA–mGFP in transfected U2OS cells. (H) LULL1 and PK–LULL1 expression similarly increase the torsinA-ΔE302/3 nuclear envelope localization Index. Mean±s.e.m. are calculated for >20 CHO cells co-transfected with GFP–torsinA-ΔE302/3 and the indicated LULL1 or control transmembrane protein. ****P<0.001 difference in nuclear envelope localization index compared with cells expressing the control protein (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis). Scale bars: 10 µm.