Abstract

Reticulohistiocytoma is a rare, benign histiocytic proliferation of the skin or soft tissue. While ocular involvement has been documented in the past, there have been no previously reported cases of reticulohistiocytoma of the orbit. In this report, the authors describe a reticulohistiocytoma of the orbit in a middle-aged woman.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to for a 1-month history of an enlarging nodule beneath her right upper eyelid. She denied any visual changes. She admitted to feeling pressure and a “twitching” feeling around the nodule. She has no significant past ocular history. Her medical history was significant for removal of a brain aneurysm several years prior and hand reconstructive surgery.

Examination showed that her best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in OU. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect. Hertel measurements at a base of 90 were 16.5 and 15.0 in the OD and OS, respectively. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 20 mm Hg OU. Slit lamp biomicroscopy showed mild nuclear sclerotic cataracts in OU. There was a palpable mass in the lacrimal fossa along the right upper eyelid with overlying periocular inflammation. A CT scan of the orbits and sella demonstrated an asymmetric prominence of the right lacrimal gland without bony changes (Fig. 1). The patient underwent a right orbitotomy and incisional biopsy without complication.

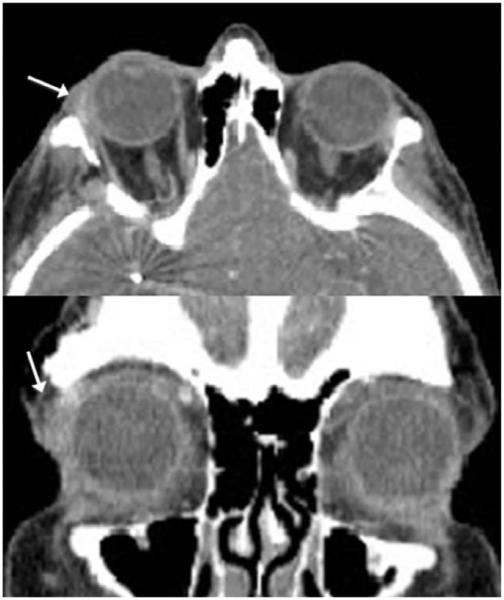

FIG. 1.

CT of orbits shows a mass in the lacrimal gland area (arrow) demonstrated by the transverse (top) and coronal (bottom) views.

Gross examination of the biopsy specimen revealed a piece of tan tissue measuring 7 × 2 × 2 mm. Microscopic examination showed a mass composed of numerous histiocytes with ground glass cytoplasm (Fig. 2). There were occasional giant cells present, and some of the histiocytes contained vacuolated cytoplasm. Rare lymphocytes were present. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for CD68 and vimentin and negative for CD1a and S100 in the histiocytes. The lymphocytes immunostained for CD3. Based on the histologic appearance and immunohistochemical stains, the diagnosis was reticulohistiocytoma (RH). This study was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant at this institution.

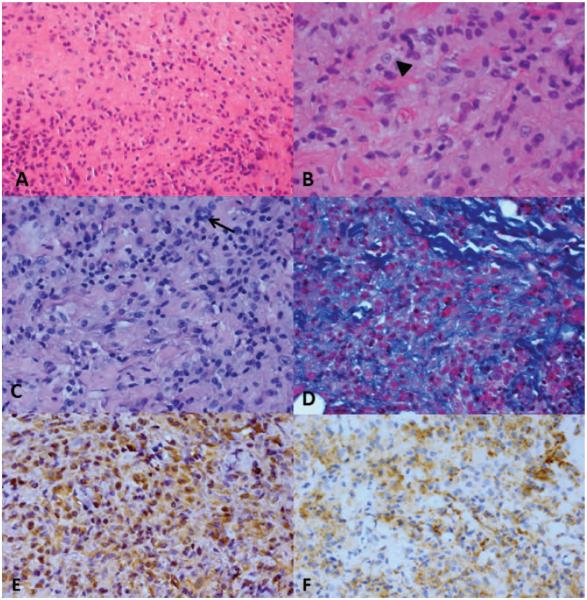

FIG. 2.

A, The mass is composed of a diffuse sheet of histiocytes with ground glass cytoplasm. B, The histiocytes contain vesiculated nuclei with prominent nucleoli (arrowhead). C, There are occasional giant cells present (arrow). D, There are intervening bundles of collagen between collections of histiocytes. Immunohistochemical stains are positive for vimentin (E) and CD68 (F) in the histiocytes. A, hematoxylin-eosin, ×100; B, hematoxylin-eosin, ×150; C, periodic acid-Schiff, ×100; D, Masson trichrome, ×100; E, and F, peroxidase anti-peroxidase, ×100.

DISCUSSION

RH, also known as solitary epithelioid histiocytoma, is a rare histiocytic proliferation of the skin or soft tissue.1 It is a nonneoplastic entity arising from macrophages rather than dendritic histiocytes. Histologically, RHs are composed of large mononuclear and multinucleated histiocytes with “ground glass” cytoplasm. The histiocytes are surrounded by a mixture of various inflammatory cells2 including granulocytes and T lymphocytes (not B lymphocytes).3 There have been 2 clinicopathologic reports of epibulbar solitary RHs and 2 reports of solitary RHs of the eyelid.3,4 The 2 epibulbar cases were localized to the limbus and cornea without skin involvement.2

RH and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis are 2 diseases that fall under the spectrum of reticulohistiocytosis. RH is an isolated lesion without systemic involvement.2 In contrast, multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is manifest by multiple nodules5 and can be differentiated from solitary RH by its association with systemic disease. Sometimes referred to as “lipoid dermatoarthritis,” patients with multicentric reticulohistiocytosis may have arthropathy,1 and there may be an associated internal malignancy.6 Both entities occur predominantly in adults. Historically, RHs occur in young adults with a slight male predominance.1 RHs are thought to be nonneoplastic, localized, cytokine-induced collection of histiocytes reacting to an unknown stimulus.1

Goette et al.7 proposed a classification system for reticulohistiocytic lesions that include the following 3 categories: solitary cutaneous RH, multiple cutaneous RHs, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. In response to this classification system after 2 cases of ocular reticulohistiocytosis were discovered, Allaire et al.2 proposed a fourth category of solitary noncutaneous RH. This case of RH of the orbit falls in this fourth category of reticulohistiocytic lesions.

There are several entities in the differential diagnosis for histiocytic lesions involving the eye and orbit including Rosai-Dorfman disease, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, juvenile xanthogranuloma, histiocytic sarcoma, and Erdheim-Chester disease (Table). According to the WHO committee and the Histiocyte Society,8 histiocytic lesions are classified according to their cell of origin. The dendritic cell-derived diseases include Langerhans cell histiocytosis, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and solitary histiocytomas of dendritic cell phenotypes. Macrophage-derived diseases include Rosai-Dorfman disease and solitary histiocytoma with the macrophage phenotype. Immunohistochemistry has elucidated these histiocytic lesions by highlighting the cell of origin. Macrophages stain positive for lysozyme, CD45, and CD14; Langerhans cells stain positive for CD45, S100, and CD1a; Dendritic cells stain positive for CD45 and S100.8

| Disease | Age | Predominant sex | Clinical presentation | Pathology | Immunohistochemistry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulohistiocytoma (Solitary epithelioid histiocytoma) |

Young adults (can occur from childhood to adulthood) |

Male | Solitary skin or soft tissue nodule, reports of orbital involvement limited to corneal and limbal involvement |

Large, mononuclear and multinucleated histiocytes with “ground glass” appearing cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells |

CD163, CD68, alpha-1 antitrypsin+ |

| Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis |

Children | No sex predilection |

Clinical variability (small bony lesion to multisystem disease); orbital involvement includes lytic defects in the orbit commonly found in the sphenoid wing |

Histiocytes admixed with eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils. Langerhans cells contain Birbeck granules. |

S100, CD1a + |

| Rosai-Dorfman Disease |

Child/young adults | Male | Skin lesions associated with bilateral, massive, painless cervical lymphadenopathy; low-grade fever, weight loss, leukocytosis |

Histiocytes with polymorphism with pale or eosinophilic cytoplasm and emperipolesis |

S100, CD68+ |

| Juvenile xanthogranuloma |

Children/young adults | Male | Dermal or subcutaneous mass (eyelid) |

Touton-type histiocytic cells; numerous eosinophilic granulocytes |

CD68, Factor XIIIa+ |

| Middle aged | No sex predilection |

Skin or soft tissues mass | Epithelioid histiocytes with nuclear atypia and mitotic activity |

Lysozyme, KiM8, S100, CD21, CD35+ |

|

| Erdheim-Chester disease |

Middle aged | No sex predilection |

Systemic disease with ophthalmic involvement limited to exophthalmos secondary to retrobulbar infiltration and xanthelasma-like lesion on the eyelid |

Dense infiltrates of foamy histiocytes, lymphocytes, monocytes, and Touton giant cells |

CD68 +, negative S100 and Cd1a |

As mentioned above and shown in Table, RHs exhibit a macrophage, histiocytic immunophenotype and therefore express CD68, CD163, and lysozyme. Rosai-Dorfman disease, otherwise known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is associated with multiple skin nodules and lymphadenopathy. The histiocytes in this disease are nonLangerhans cells and usually S100 positive.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a histiocytic disease that occurs in children and commonly presents as a lytic defect affecting the superotemporal orbit or sphenoid wing.9 In contrast to Rosai-Dorfman disease, Langerhans cell histiocytosis cells bear the Langerhans cell granule (Birbeck granule) and are CD1a and S100 positive. Juvenile xanthogranuloma is an uncommon inflammatory condition that is predominantly found in children2 and classically contain Touton-type histiocytic giant cells with numerous eosinophilic histiocytes.1 The cells in juvenile xanthogranuloma immunostain for CD68 and usually Factor XIIIa; however, they do not contain Birbeck granules. Histiocytic sarcoma is a rare tumor that can present in any tissue. It is composed of epithelioid histiocytes with nuclear atypia and mitotic activity.1 Erdheim-Chester disease is a rare form of histiocytosis characterized by bone, heart, lung, liver, kidney, and brain involvement. It can rarely present with retrobulbar infiltration causing proptosis or xanthelasma-like lesions on the eyelid.10,11 This case was interpreted to represent a solitary RH by its positive staining for CD68, vimentin, alpha-1 antitrypsin and negative staining for CD1a and S100. The case presented above is an unusual case of RH of the orbit.

The patient presented has an isolated orbital nodule unassociated with systemic disease. Histopathologically, the lesion was composed of large mononuclear cells, histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, and a few dispersed multinucleated cells. Immunohistochemical stains for CD68 and vimentin along with negative stains for S100 and CD1a confirmed the diagnosis as a RH with a macrophage histiocytic origin. RH should be considered in the differential of a benign, painless orbital lesion.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by NIH P30EY06360 and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521, 8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaire GS, Hidayat AA, Zimmerman LE, et al. Reticulohistiocytoma of the limbus and cornea. A clinicopathologic study of two cases. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1018, 22. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakobiec FA, Kirzhner M, Tollett MM, et al. Solitary epithelioid histiocytoma (reticulohistiocytoma) of the eyelid. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1502, 4. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakri SJ, Carlson JA, Meyer DR. Recurrent solitary reticulohistiocytoma of the eyelid. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19:162, 4. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000056024.60199.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagle RC, Jr, Penne RA, Hneleski IS., Jr Eyelid involvement in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:426, 30. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suwabe H, Tsutsumi Y. Reticulohistiocytoma involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue and a regional lymph node. Pathol Int. 1996;46:531, 7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1996.tb03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goette DK, Odom RB, Fitzwater JE., Jr Diffuse cutaneous reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:173, 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee On Histiocytic/ Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:157, 66. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199709)29:3<157::aid-mpo1>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo KI, Harris GJ. Eosinophilic granuloma of the orbit: understanding the paradox of aggressive destruction responsive to minimal intervention. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19:429, 39. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000092800.86282.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann EM, Müller-Forell W, Pitz S, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: a case report. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:803, 7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexiev BA, Staats PN. Erdheim-Chester disease with prominent pericardial effusion: cytologic findings and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. doi: 10.1002/dc.22957. [published online ahead of print February 28, 2013] doi: 10.1002/dc.22957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strehl JD, Stachel KD, Hartmann A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma developing after treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:720, 5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, et al. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology. 2002;41:1, 29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]