Abstract

Objectives

We examined whether apparent redundancy in a cumulative meta-analysis of trials is justified by concern about bias, random error or generalisability of the results.

Design

Cumulative meta-analysis, risk of bias assessment, trial sequential analysis, description of study participants over time and a review of rationales for conducting trials.

Data source

126 randomised trials included in a systematic review assessing of tranexamic acid on blood transfusion in surgery.

Results

The cumulative meta-analysis including all trials shows that the pooled estimate first reached statistical significance after the second trial in 1993. When the analysis was limited to the 38 high-quality trials and adjusted to account for potential systematic and random errors, the uncertainty was resolved after the 22nd trial in 2008. When the analysis was restricted to the two high-quality, prospectively registered trials, the cumulative z-curve crossed p=0.05 but not the monitoring boundary, suggesting an early potentially spurious statistically significant result. As precision of the pooled estimate increased, the number of trials initiated increased, although trial activity appeared to move to other surgery types. Most (62%) reports cited at least one systematic review. Of 118 reports examined, concern about generalisability was the reason for initiating the trial in 60%. Other reasons were to address a question other than the effect on bleeding (26%) and to confirm previously observed results (4%). Unawareness of previous research was apparent in 4% trials, while the rationale was unclear in 3%.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that poor quality is a more important cause of redundant research than the failure to review existing evidence. Concerns about generalisability of results is the main motivation for new trials. Contrary to previous claims, our results suggest that systematic reviews showing treatment effects can stimulate an increase in trial activity rather than reduce it.

Keywords: systematic reviews, meta-analysis, tranexamic acid

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The results are based on data from a comprehensive and up-to-date systematic review of trials assessing the effect of tranexamic acid (TXA) in all surgery types.

The results challenge the view that the failure to systematically review existing evidence is the main cause of research redundancy.

The examination of reasons for initiating new trials is based on the rationales given in the trial reports which may not accurately reflect the rationale.

The results are based on trials of TXA in surgery, and although the extent to which the findings apply to other topics is questionable, similar observations have been made elsewhere.

Introduction

Results from cumulative meta-analyses are often cited as proof that many researchers fail to systematically review the evidence from existing trials before initiating new trials. For example, a cumulative meta-analysis of aprotinin in cardiac surgery1 showed that trials were initiated long after the pooled estimates showed a statistically significant effect. Commenting on the paper, Chalmers2 observed that it “compellingly demonstrates why all new research—whether basic or applied—should be designed in the light of scientifically defensible syntheses of existing research evidence, and reported setting the new research ‘in the light of the totality of the available evidence’”. Similar conclusions have been made on the basis of other cumulative meta-analyses.3–5

When the apparently redundant aprotinin trials were conducted, systematic reviews were relatively uncommon and failure to review the previous trials was a plausible explanation for the redundancy. However, given the increase in published reviews and their easy availability, lack of awareness of what has gone before is nowadays a less credible explanation for redundancy. We found that seemingly redundant trials of the effect of tranexamic acid (TXA) on blood transfusion were conducted even though many of them cited a systematic review concluding that the uncertainty had been resolved.6 Habre et al7 found that 73% of trials of an anaesthetic intervention cited a systematic review showing that the uncertainty about its effects had been resolved. They also observed that the number of new trials increased after publication of the review and suggested that the strong pressure to publish and the failure of ethics committees to ensure the clinical relevance of new trials could be the main reasons.

We considered two alternative explanations for the apparent redundancy. First, the trialists may be sceptical about the results of even seemingly conclusive reviews. Such scepticism may arise from concerns about systematic or random errors distorting the results. Poor-quality trials can introduce bias and multiple statistical testing as new trials accumulate may increase the risk of false-positive results. Second, even in the absence of substantial bias or random error, there may be a reluctance to generalise trial results to different patient groups. If this were the case, strong evidence of a treatment effect might be expected to lead to more trial activity rather than less, as researchers examine the impact of patient or intervention characteristics on the results.

We used data from a cumulative meta-analysis of trials examining the effect of TXA on blood transfusion in surgery, to explore whether deficiencies in the quality of the evidence justify the continuation of trial activity. We explored the impact of trial quality on effect estimates and used trial sequential analysis to quantify required information sizes and construct monitoring boundaries to assess the risk of random error affecting the cumulative estimate. We examined whether patient characteristics changed over time and the reasons given by the trial investigators for conducting their trial.

Methods

Systematic review

We extracted data from trials included in our previous systematic review of TXA for surgical bleeding. The methods used to identify trials are described in detail elsewhere.6 Briefly, we searched for all randomised controlled trials comparing TXA with placebo or a no-treatment control. We searched the Cochrane central register of controlled trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, using a combination of subject headings and text words to identify randomised controlled trials of any antifibrinolytic drug (see online supplementary file for MEDLINE search strategy). We updated our searches to May 2014 to incorporate trials published since the original version of the review. Data were extracted on patient characteristics, type of surgery and the number of patients who received a blood transfusion. We used the Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias in the included trials.8 We assessed the risk of bias associated with the method of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding and the completeness of outcome data. Trials were rated as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias for each domain. We considered trials with adequate allocation concealment and blinded outcome assessment to be at low risk of bias.

Analysis

Systematic review and meta-analyses

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs to assess the effect of TXA on blood transfusion. We pooled the data in a fixed-effect cumulative meta-analysis based on date of publication. We conducted separate meta-analysis for all trials, trials at low risk of bias and trials at low risk of bias that had prespecified blood transfusion as outcome on a registration record.

Trial sequential analyses

We used trial sequential analyses (TSA) to examine the reliability of the cumulative meta-analysis. TSA involves calculating the number of participants (ie, information size) required before the result of a meta-analysis can be considered reliable and constructs statistical monitoring boundaries to account for type I and II errors due to multiple testing.9 We conducted three analyses: (1) all trials, (2) trials at low risk of bias and (3) prospectively registered, low risk of bias trials with blood transfusion as a prespecified outcome. We calculated the required meta-analysis information size assuming a type I error of 5% and 90% power, a baseline event rate of 40% and a relative risk reduction of 15%. We chose a relative risk reduction of 15% as we judged this to represent a minimally clinical important effect. The estimate was adjusted for maximum anticipated heterogeneity of I2=75%.

We used Microsoft Excel, STATA V.13,10 RevMan V.5.311 and the TSA Software V.0.9 β12 for the analyses.

To explore the hypothesis that reliable demonstration of a treatment effect leads to an increase in trial activity, we plotted the precision of the pooled effect estimate (described by the SE of the cumulative pooled RR) against the number of new trials initiated (defined as start date of recruitment) per year. We did this both for all trials and for the subset of cardiac surgery trials.

We also plotted the publication date of each trial stratified by surgery type.

We examined trial reports to explore the reasons given for trial initiation and categorised the reasons into main themes.

Finally, we explored how the size and quality of trials changed over time. We compared the mean sample size and the proportion of trials at low risk of bias that were published before and after the Cochrane systematic review by Henry et al.13 This systematic review was chosen as it was the first and most comprehensive review conducted on the effect of TXA in surgical bleeding. The review was published in October 1999. We allowed for a 5-year time lag for the results of the review to have an impact on published research and compared trials published before and after 1 November 2004.

Results

Systematic review and meta-analyses

We found 126 trials with 12 429 patients of the effect of TXA on blood transfusion in surgery with data suitable for analysis. One hundred and twenty trials (95%) were conducted in a single centre. The median sample size was 79 patients (range 10–660). The trials involved cardiac (n=51), orthopaedic (n=49), obstetric and gynaecological (n=10), cranial (n=9), urological (n=3), hepatic (n=2), vascular (n=1) and abdominal (n=1) procedures. Thirty-eight (30%) trials had adequate allocation concealment and blinded outcome assessment and were considered at low risk of bias. We identified a clinical trial registration record for 24 (19%) trials. Six (5%) trials had been prospectively registered, four (3%) of which had prespecified blood transfusion as an outcome and two of these (2%) were at low risk of bias. Allowing for a 12-month publication time lag, 110 of the 118 (93%) trial reports published as journal articles were published when at least one systematic review was available. Examination of the reference lists showed that 68 (62%) cited one of the available systematic reviews.

Based on all 126 included trials, TXA administration appeared to reduce the risk of receiving a blood transfusion by 38% (pooled RR=0.62; 0.59 to 0.65; p<0.0001). The cumulative estimate was statistically significant (p<0.05) after the second trial (published in August 1993) and remained so thereafter. Based on data from the 38 trials at low risk of bias, TXA appeared to reduce the risk of receiving a blood transfusion by 32% (pooled RR=0.68; 0.63 to 0.73; p<0.001). The cumulative estimate was first statistically significant after the fourth high-quality trial but remained statistically significant after the sixth trial. When the analysis was limited to the two low risk of bias, prospectively registered trials that prespecified blood transfusion as an outcome measure, TXA appeared to reduce the risk of transfusion by 21% (pooled RR=0.79; 0.71 to 0.87; p<0.001).

Trial sequential analyses

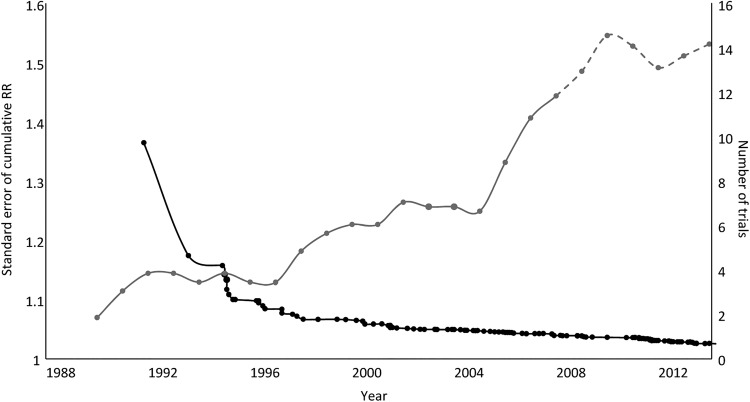

Figure 1 shows the results of the TSA. The required information size was estimated at 10 888 patients.

Figure 1.

Results of trial sequential analyses for (A) all trials, (B) trials at low risk of bias and (C) low risk of bias trials with transfusion prespecified on prospective registration record. For each analysis an information size is calculated on the basis assuming α=5%, β=10%, control group event rate of 40%, relative risk reduction of 15% and anticipated maximum heterogeneity of I2=75%. The solid black line illustrates the cumulative z-curve, the solid grey line shows the trial sequential monitoring boundary.

Based on data from all 126 trials, there appears to be strong evidence that TXA reduces the risk of blood transfusion in surgery. The z-curve crosses the monitoring boundary before the heterogeneity-adjusted information size is achieved when the 28th trial was published in March 2001. Prior to this point, there were 26 potentially spurious p values. Since the monitoring boundary was crossed, a further 98 trials have been published.

Based on the 38 low risk of bias trials, there appears to be strong evidence that TXA reduces blood transfusion. The z-curve crosses the monitoring boundary after the 22nd high-quality trial published in November 2008. Prior to this point, there were 18 potentially spurious p values. Since the monitoring boundary was crossed, a further 15 high-quality trials have been published.

When the analysis is restricted to the two low risk of bias trials which had prespecified blood transfusion as an outcome, the z-curve does not cross the monitoring boundary and the heterogeneity-adjusted information size is not achieved. There is one potentially spurious p value.

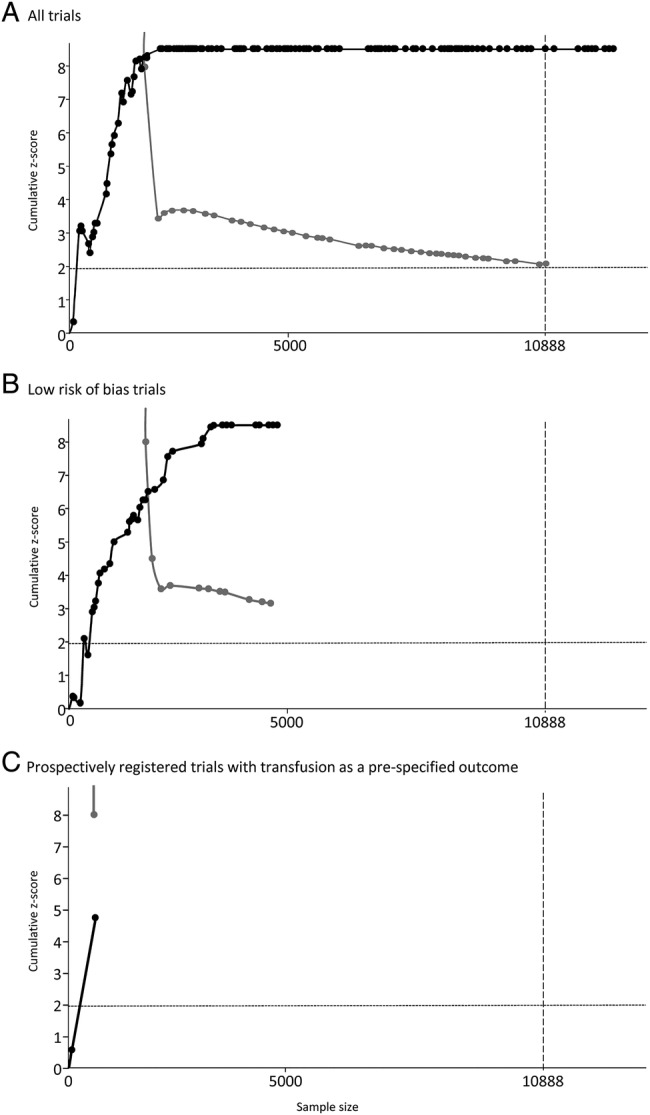

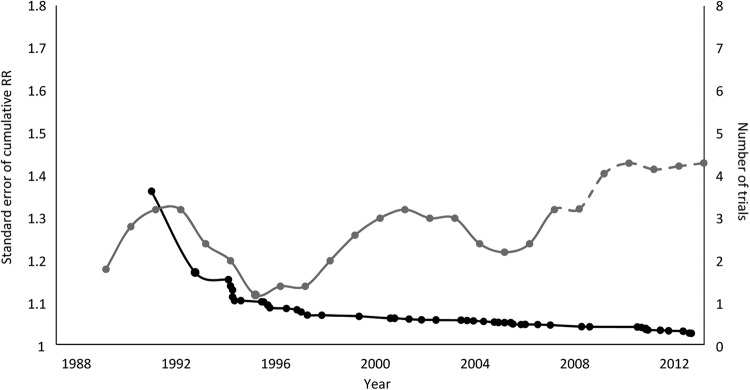

Figure 2 shows the precision of the cumulative pooled estimate (SE of the log cumulative RR) and the number of trials initiated per year from 1991 to 2014. As the precision of the pooled estimate increases (ie, decrease in the SE), the number of new trials initiated each year also increases. A similar pattern is observed for trials in cardiac surgery (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Precision of the cumulative pooled estimates described by the SE of the risk ratios (RRs; left hand axis) and the number of trials (5-year moving averages, right hand axis) initiated per year.

Figure 3.

Precision of the cumulative pooled estimates for the effect of tranexamic acid in cardiac surgery described by the SE of the risk ratios (RRs; left hand axis) and the number of trials (5-year moving averages, right hand axis) initiated per year.

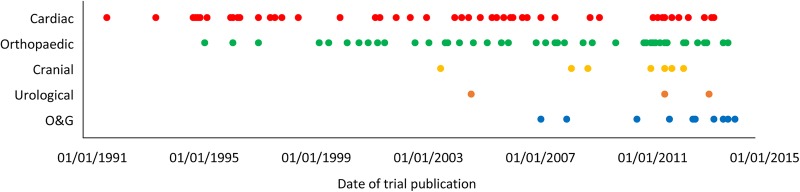

Figure 4 shows a timeline of the publication of the trials, stratified by surgery type. It appears that trials were first conducted in cardiac surgery and shortly afterwards in orthopaedic surgery. Trial activity then expands to other types of surgery namely cranial, urological and gynaecological surgery.

Figure 4.

Timeline of publication of trials of TXA stratified by type of surgery (TXA, tranexamic acid; O&G, obstetric and gynaecological).

Qualitative review of trial justifications

Eight trials were reported in abstract or summary form only, leaving 118 trials reported in sufficient detail to extract information on the rationale. A summary of the extracted information is shown in table 1. Concerns about the generalisability of the available evidence was used to justify 71 (60%) trials. These trials sought to replicate a previously observed beneficial effect of TXA on surgical bleeding but in a different group of patients, such as those undergoing a different type of surgical procedure. Thirty-one (26%) trials were initiated to answer a different research question to the effect of TXA on bleeding. Most of these trials were conducted to examine the effect of different doses or timings of TXA despite the inclusion of a placebo or no-TXA control group. Five (4%) trials appeared to have been conducted because of a failure to synthesise prior evidence. The trial rationale was unclear in 4 (4%) trials.

Table 1.

Summary of reasons for initiating trials of tranexamic acid for surgical bleeding based on information extracted from the final reports

| Failure to synthesise evidence | Confirmatory | Generalisability | Assessing a different research question | Unclear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trials citing ≥1 available systematic review (n=68) | – | 2 | 51 | 11 | 4 |

| Trials not citing an available systematic review (n=42) | 2 | 3 | 21 | 16 | – |

| Trials published before a systematic review was available (n=9) | 3 | – | – | 6 | – |

| All trial reports (n=118) | 5 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 72 (61%) | 33 (28%) | 4 (3%) |

Comparison of trials conducted before and after publication of the Henry et al systematic review

Of the 126 trials, 47 (37%) were published before 1 November 2004 compared with 79 (63%) published afterwards up to May 2014. The average sample size had increased between the two periods (mean±SD, 64±50 vs 119±103; p<0.0001). A larger proportion of trials published after November 2004 were judged to be at low risk of bias for both allocation concealment and blinding (12 (26%) vs 28 (35%); p=0.23).

Discussion

Principal findings

We examined two hypotheses for the redundancy in a cumulative meta-analysis. First, that despite the apparently conclusive results, legitimate concerns about bias and random error justified new trials. We found some support for this. Most trials were small, single centre, low quality and hardly any were prospectively registered. Nevertheless, when only high-quality trials were considered, with steps taken to reduce the risk of false-positive results, there remained strong evidence that TXA reduces transfusion.

Our second hypothesis was that new trials are conducted because of concerns about the generalisability of the results. We found strong support for this. Increasing evidence that TXA decreases the need for blood transfusion resulted in more trial activity and not less. The change in patient characteristics over time and the rationales given by trialists also indicate that generalisability concerns motivated the new trials. That over half of trials cited at least one of the existing systematic reviews suggests that ignorance of the existing evidence does not fully explain ongoing trial activity.

The average sample size of trials has increased, and there is some suggestion that the quality of trials has improved over time.

Strengths and weaknesses

We examined trial reports to find the reasons authors gave for conducting new trials. This process was inevitably subjective and different assessors might have made different judgements. Furthermore, trial reports might not accurately reflect the rationale at trial inception. We did not contact authors, although whether this would have provided more reliable information is uncertain. There are other, non-scientific motivations, such as monetary and academic, for initiating a new trial which would not be publically reported. Nevertheless, the reasons given in trial reports are the openly given justifications that are accepted by the scientific community and are therefore a reasonable focus for review.

Our study was based on clinical trials of TXA in surgery, and the extent to which the results apply to other topics is questionable. However, we have also found that publication of a systematic review showing strong evidence that TXA reduces mortality in bleeding trauma patients also resulted in increased trial activity rather than less. A 2004 systematic review of TXA in acute traumatic injury14 found no eligible trials even though TXA was commonly used in other bleeding conditions. The review prompted the Clinical Randomisation of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Haemorrhage (CRASH-2) trial which included 20 211 bleeding trauma patients and showed that TXA reduces death due to bleeding and all-cause mortality.15 The subsequently updated review included two trials and reported that the uncertainty had been resolved.16 Nevertheless, some authors, pointing out that many of the patients in the CRASH-2 trial were recruited from hospitals in Africa, Asia and Latin America, questioned whether the results can be applied in ‘modern’ trauma care systems17 and have initiated new clinical trials rather than implementing the results.18 19 Although subgroup analyses show that the CRASH-2 trial results do not vary by geographical region,20 two placebo-controlled trials are underway.14 15 Habre et al7 also found that publication of a conclusive review coincided with increased trial activity and that most new trials cited the conclusive review.

There are other potential explanations for the continuation of trial activity that we have not explored. Habre et al suggested that redundant trials of an anaesthetic intervention may have been motivated by the self-interest of researchers wishing to gain more research publications. In relation to our study, trials of the effect of TXA on blood transfusion are relatively easy to conduct, and since a treatment effect is highly likely, it would be an attractive topic for research.

Implications

Our results raise questions about the process of scientific generalisation. If there is strong evidence that TXA reduces bleeding in cardiac and orthopaedic surgery, is it necessary to examine its effect in obstetric surgery? Rothman et al21 argues that the reluctance to generalise results to populations that were not represented in the original research confuses statistical and scientific inference. Statistical inference, the process of using sample information to reach conclusions about the population from which it was drawn, is helped by having a representative sample. However, generalising trial results involves scientific inference, a process of reaching general conclusions about how a treatment works. The main prerequisite for scientific inference is a biological insight into the mechanism of action of the treatment and an awareness of the circumstances that may be relevant to this mechanism. Rather than using statistical reasoning, it is more appropriate to use biological reasoning and ask whether there is any good reason why TXA would work differently in orthopaedic or urological surgery?

A further concern is the number of inappropriately designed trials. This typically concerns trials which aimed to build on the existing knowledge by comparing different doses or timings of TXA, yet opted to include a no-treatment comparison group. The inclusion of a no-treatment comparison group in such trials is wasteful and unethical—failings that implicate both trialists and the ethical review committees approving the trials. In this article, we focus on the potential explanations for trialists’ decision to initiate further trials of TXA, yet there is also a question regarding why patients continue to agree to participate in apparently ‘redundant’ trials in which there is a chance they will forego receiving an effective treatment. We did not attempt to obtain the patient information sheets used in the trials, and there remains an unanswered question regarding the extent to which trial participants are made aware of the existing evidence as part of the consent giving process.

Our results suggest that low-quality trials are a more important cause of ‘research waste’ than the failure to systematically review the existing evidence. When only high-quality trials are considered, the number of statistically ‘redundant’ trials was reduced from 98 to 15. Most trial reports clearly indicated an awareness that TXA had been shown to reduce bleeding but sought to examine its effect in different types of surgery. For this reason, more systematic reviews and greater attention to existing reviews will only increase research waste unless determined efforts are made to increase quality in the form of adequately powered trials that are properly randomised with adequate allocation concealment and blinding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Prieto-Merino for statistical advice and Iain Chalmers for comments on an earlier version of this article.

Footnotes

Contributors: KK and IR conceived the study. KK extracted the data and conducted the analyses. KK and IR wrote the manuscript. The final version was approved by both authors. KK is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Ian Roberts is a National Institute for Health Research senior investigator.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Fergusson D, Glass KC, Hutton B et al. Randomized controlled trials of aprotinin in cardiac surgery: could clinical equipoise have stopped the bleeding? Clin Trials 2005;2:218–29. 10.1191/1740774505cn085oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers I. The scandalous failure of science to cumulate evidence scientifically. Clin Trials 2005;2:229–31. Comment. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke M, Brice A, Chalmers I. Accumulating research: a systematic account of how cumulative meta-analyses would have provided knowledge, improved health, reduced harm and saved resources. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102670 10.1371/journal.pone.0102670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert R, Salanti G, Harden M et al. Infant sleeping position and the sudden infant death syndrome: systematic review of observational studies and historical review of recommendations from 1940 to 2002. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:874–87. 10.1093/ije/dyi088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark O, Adams JR, Bennett CL et al. Erythropoietin, uncertainty principle and cancer related anaemia. BMC Cancer 2002;2:23 10.1186/1471-2407-2-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P et al. Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e3054 10.1136/bmj.e3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habre C, Tramer MR, Popping DM et al. Ability of a meta-analysis to prevent redundant research: systematic review of studies on pain from propofol injection. BMJ 2014;348:g5219 10.1136/bmj.g5219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, eds. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brok J, Thorlund K, Gluud C et al. Trial sequential analysis reveals insufficient information size and potentially false positive results in many meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:763–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.StatCorp, Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] Version 5.3 Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.TSA Software version 0.9 beta. Copenhagen Trial Unit, 2011.

- 13.Henry DA, Moxey AJ, Carless PA et al. Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1999;(1):CD001886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coats T, Roberts I, Shakur H. Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD004896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R et al. , CRASH-2 Collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61479-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts I, Shakur H, Ker K et al. , CRASH-2 Trial Collaborators. Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(1):CD004896 10.1002/14651858.CD004896.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruen RL, Jacobs IG, Reade MC. Tranexamic acid and trauma. Med J Aust 2014;200:255 10.5694/mja13.00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown JB, Neal MD, Guyette FX et al. Design of the Study of Tranexamic Acid during Air Medical Prehospital Transport (STAAMP) Trial: addressing the knowledge gaps. Prehosp Emerg Care 2015;19:79–86. 10.3109/10903127.2014.936635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitra B, Mazur S, Cameron PA et al. Tranexamic acid for trauma: filling the ‘GAP’ in evidence. Emerg Med Australas 2014;26: 194–7. 10.1111/1742-6723.12172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ker K, Kiriya J, Perel P et al. Avoidable mortality from giving tranexamic acid to bleeding trauma patients: an estimation based on WHO mortality data, a systematic literature review and data from the CRASH-2 trial. BMC Emerg Med 2012;12:3 10.1186/1471-227X-12-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1012–14. 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]