Abstract

Purpose

Epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) plays a critical role in the control of Na+ balance and the development and progression of exocrine gland pathology. The aim of the present study was to investigate the presence of ENaC in the rabbit lacrimal gland (LG) and its potential changes during induced autoimmune dacryoadenitis (IAD)and pregnancy.

Methods

Total mRNA of α, β, and γ subunits was extracted from whole LG,acinarand ductal cells by laser capture micro dissection (LCM) for real time RT-PCR. LG were processed for Western blot and immunofluorescence.

Results

mRNA for both α and γ was expressed in whole LG lysates while β was undetectable. In rabbits with IAD, the levels of mRNA for α and γ were 20.9% and 58.9% lower (p<0.05) while no significant changes were observed in term-pregnant rabbits (p=0.152). However, we were unable to detect mRNA of any subunit in LCM specimens of ductal cells due to their extremely low levels. Western blot demonstrated bands for both α (90kDa) and γ (85kDa) but β was undetectable. In rabbits with IAD, densitometry analysis showed that expression of α decreased 22% while γ decreased 26% (p<0.05). In pregnant rabbits, however, α expression was 31% lower while γ was 34% lower (p<0.05). From immunofluorescence studies, all subunits were present in ductal cells whereas virtually no immunoreactivity was detected in acini. No noticeable changes of their distribution pattern and intensity were found in rabbits with IAD or during pregnancy.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated the presence of ENaCin the rabbit LG and its alterations in IAD and pregnancy, suggesting that ENaC may contribute to the pathogenesis of altered LG secretion and ocular surface symptoms in these animals.

Keywords: epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), lacrimal gland, Sjögren’s syndrome, pregnancy, dry eye

1. Introduction

Fluid produced by lacrimal gland (LG) is the major component of tears in the ocular surface. When its quantity and/or quality are altered, dry eye may ensue and manifest as a plethora of symptoms. Dry eye affects millions of people, with the vast majority being women, especially those after menopause.1

Although most LG studies have focused on acinar cells, increasing evidence indicated that the LG ducts also play critical roles in lacrimal secretion,2–6 suggesting a two-stage process of production: 1) secretion of primary fluid in the acini; and 2) modification by ductal cells into the final fluid, which eventually exit onto the ocular surface. Like other exocrine secretions, LG fluid secretion is an osmotic process mediated by many ion transporters/channels and aquaporins.2,7–13

The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), comprised of α, β, and γ subunits, plays a critical role in the control of Na+ balance, blood volume and pressure, and viscosity of extracellular fluid.14 It has been identified in many epithelial tissues including lung, kidney, colon, sweat and salivary glands.15–17 ENaC activity comprises the rate-limiting step for Na+ entry into cells, which is then extruded into the interstitium via Na+ K+-ATPase located on the basolateral membranes.16

Studies in kidney tubules, colon, sweat and salivary glands, respiratory tract, and taste buds indicated that ENaC plays a major role in their physiology and pathophysiology.18–22 In salivary glands, an exocrine gland that is anatomically and functionally very similar to LG and also involved in Sjögren’s syndrome, ENaC has been shown to mediate NaCl absorption in salivary gland duct in the production of normal, NaCl-depleted saliva.19,23

However, there have never been any investigations regarding the expression of ENaC and its potential contribution to LG secretion and dysfunction. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the expression of ENaC subunits and their potential alteration in two rabbit models that demonstrated LG pathology and abnormalities of the ocular surface: rabbits with induced autoimmune dacryoadenitis (IAD) and pregnancy. IAD is an excellent rabbit model of Sjögren’s syndrome,24–26 an autoimmune disease that causes functional deficiency of LG and salivary glands, and has been used extensively to study its pathophysiology. Our previous reports also indicated that pregnant rabbits, as a physiological state rather than a pathological condition like IAD, also demonstrated dry eye symptoms and LG pathologies.27,28

2. Methods

2.1. Animals tissue preparations

New Zealand White adult female rabbits (Irish Farms, Norco, CA) weighing about 4.0 kg were used. One group consisted of three female rabbits with IAD, and the other consisted of three age- and sex-matched normal controls. Three pregnant rabbits were time dated with day zero corresponding to the date of coitus. Because normal gestation in the rabbit is 31 days, term pregnant rabbits were sacrificed on the 29th day of pregnancy.

To generate the IAD model, epithelial cells from one LG were first co-cultured with the same rabbit’s ex vivo-activated lymphocytes for two days and then injected into the same rabbit’s remaining LG. The rabbits typically developed IAD within two weeks. The detailed procedures have been published previously.24–26

The rabbits were narcotized with a mixture of ketamine (40 mg/ml) and xylazine (10 mg/ml) and given an overdose of Nembutal (80 mg/kg) for euthanasia. One inferior LG was removed and embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound while the other was frozen in liquid nitrogen. Both were stored at −80°C until use. All studies conformed to the standards and procedures for the proper care and use of animals by the US Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Laser Capture Micro dissection (LCM), RNA extraction, and reverse transcription

LCM was used to collect purified acinar cells and epithelial cells from various duct segments, as we described before.2 However, due to the extremely low level of ENaC subunits, we were unable to detect the presence of their mRNA. Total cellular RNA was isolated from RNA later-treated specimens with an RN easy® Midi Kit plus on-column DNase digestion to reduce the possibility of DNA contamination (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality and quantity was evaluated using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Five micrograms of total RNA specimens were then reverse-transcribed to cDNA only if the 260/280 ratio was above 1.9 (High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit containing random primers and MultiScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Real time RT-PCR Analysis

The sequences of primers and probes of ENaC α, β, and γ subunits used in this study are listed in Table 1. The sequences were designed using Primer Express from Applied Biosystems (ABI) and synthesized by ABI. All probes incorporated the 5’ reporter dye 6-carboxyfluorescin (FAM) and the 3’ quencher dye 6-carboxytertramethylrhodamine (TAMRA).

Table 1.

Primers and probes used for real-time RT-PCR

| Gene | Forward Primer | Tm (° C) | Reverse Primer | Tm (° C) | Product Size (bp) | Probe | Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENaCα | 5'-GGTGCACGGACAGGATGAG-3' | 54.75 | 5'-CCGGGCCGCAAGTTAAA-3' | 52.25 | 60 | 5'-CTGCCTTTATGGATGATGGCG-3' | AF229025 |

| ENaCβ | 5'-GCAGAACCTCTACGGCAGTTACA-3' | 56.59 | 5'-TTGGAAGCAGGAGCGAAGA-3' | 53.12 | 67 | 5'-CACCACCTACTCCATCCAGGCCT-3' | AF229026 |

| ENaCγ | 5'-TCCATCGGCAGGACGAATA-3' | 52.37 | 5'-ACATGGCCGTCTCGATCTCT-3' | 54.89 | 63 | 5'-CCCTTCATTGAAGATGTGGGCA-3' | AF229027 |

For real-time RT-PCR, amplification was carried out on an ABI PRISM® 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) containing the internal dye, ROX, as a passive reference. Detailed procedures were described in our previous report.2 Each specimen was measured in triplicate and the difference between the CT values of each target mRNA and the internal housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was used to calculate the level of target mRNA relative to the level of GAPDH mRNA in the same specimen.

2.4. Immunofluorescence and Microscopy

Primary antibodies used were all purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. The dilutions of antibodies against ENaCα subunit (goat polyclonal, sc-22239),β subunit (goat polyclonal, sc-22242), and γsubunit (goat polyclonal, sc-22245) were 1:10, 1:200, and 1:100, respectively. The secondary antibody used was fluoresce in isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), at a dilution of 1:200. Rhoda mine conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), at the dilution of 1:200, was also used to stain F-actin to show the morphological profiles of LG.

Slides were observed with a Leica epifluorescence microscope and a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope. FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were visualized by excitation at 488 nm using an argon laser. Images were analyzed with LSM image browser and Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

2.5. Western Blot

LG were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mMTris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mMNaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X 100, 1% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL aprotinin, 1 µg/mL leupeptin) and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 20 minutes. Supernatant was denatured in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 20 minutes at 60 °C, resolved on a 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and then transferred onto PVDF (Millipore Immobilon-P, Billerica, MA). To assess transporter proteins, a constant amount of proteins from each specimen was analyzed. Membrane blots were probed with antibodies against ENaCαsubunit at the dilution of 1:250, β at 1:200, and γat 1:250. Blots were incubated with Alexa 680-labeled donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (Invitrogen) and detected with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Densitometry analysis of resulting gel was performed using the manufacturer’s software.

2.6. Statistics

Data were presented as mean±SEM. Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to evaluate the significance of the differences; p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1 Expression of mRNA

The expression of mRNA for ENaC subunits was extremely low in LG (Fig. 1). In fact, it was so low that we were unable to detect their presence in epithelial specimens obtained from LCM(detection limit was 2 ng/µL).

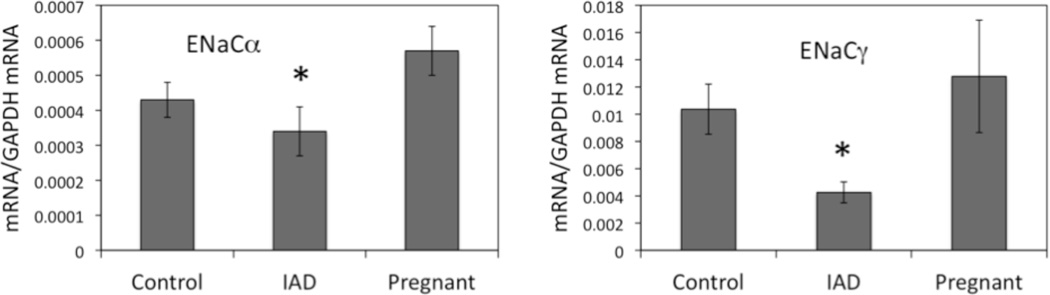

Figure 1.

α:In specimens from whole LG lysates, mRNA for αsubunit was 0.00043±0.00005 in control animals while its level was 20.9% lower (P<0.05) in rabbits with IAD (0.00034±0.00007). The mRNA level was 0.00057±0.00007 in pregnant rabbits. While it was higher than that of normal control animals, no significant difference was detected (p=0.247).

β: The mRNA level for βsubunit was so low that we were unable to detect its expression in specimens from whole LG lysates.

γ: For γ subunit, its mRNA level was 0.01037±0.00184 in control rabbits, and 58.9% lower (P<0.05) in rabbits with IAD (0.00426±0.00077). Similar toα subunit, mRNA for γsubunit was 0.01278±0.00413 in pregnant rabbits, not significantly different than that of normal control animals (p=0.184).

3.2 Western Blot and Densitometry

In addition to RT-PCR studies, Western blot was used to investigate the potential changes of protein expressions. Immunoblots of whole LG homogenates indicated that there were significant changes in the expressions of both α and γsubunits during IAD and pregnancy (Fig. 2). No protein expression was detected for β subunit.

Figure 2.

In rabbits with IAD, densitometry analysis showed that expression of αsubunit decreased 22% (P<0.05), while γsubunit expression decreased 26% (P<0.05), consistent with their decreases at mRNA level. In pregnant rabbits, however, αsubunit expression was 31% lower andγ 34% lower (P<0.05), whereas no significant change of their mRNA was detected when compared to control.

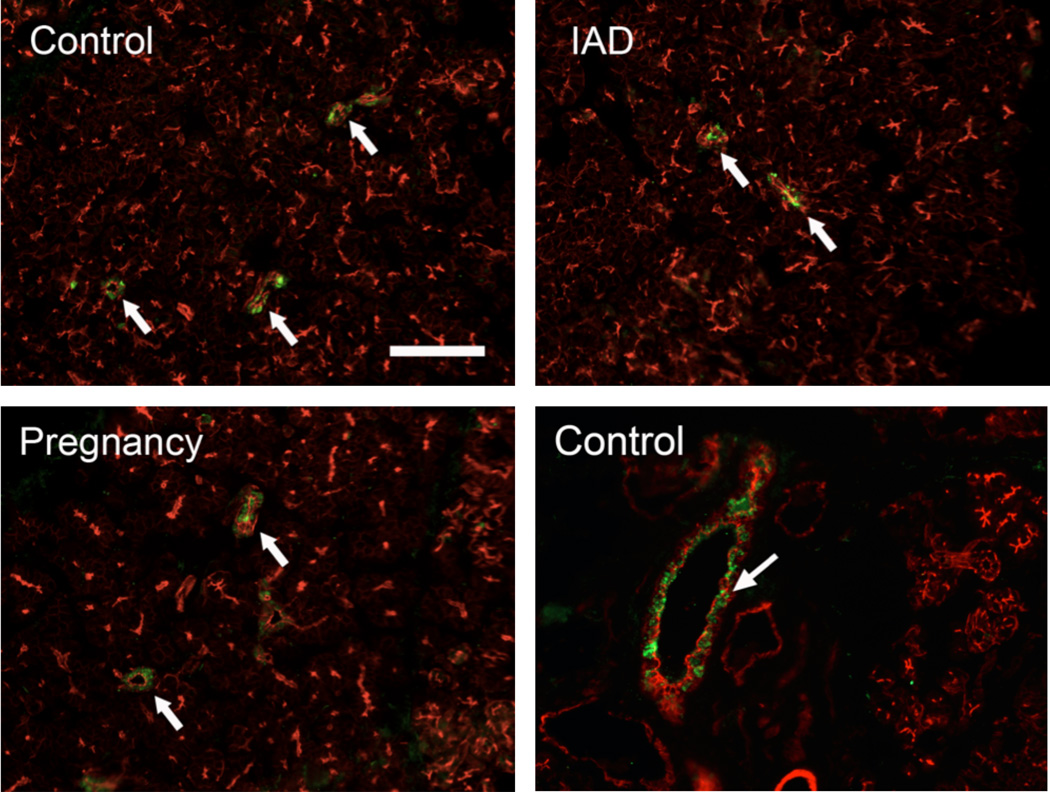

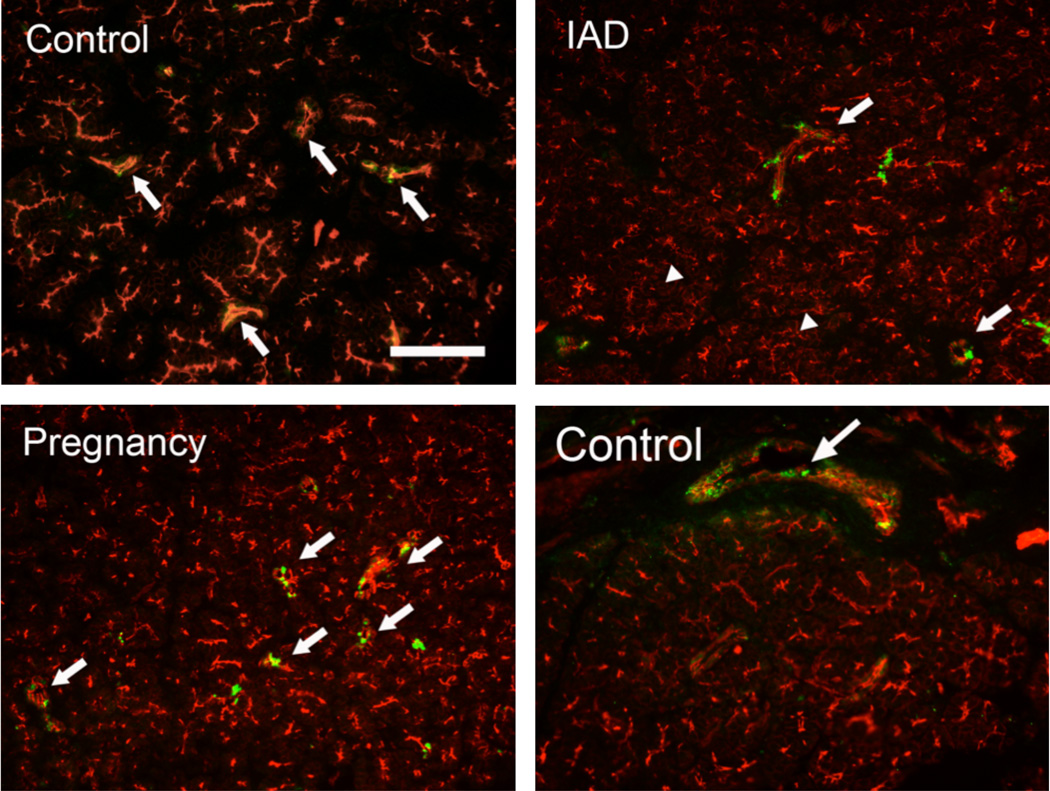

3.3 Immunofluorescence

Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin, which stains F-actin as intense red, was used to outline the morphological profile. In normal control rabbits, the immunoreactivity (IR) of α, β, and γappeared to be in ductal cells only (Figs. 3, 4, 5), with virtually no IR detected in acini. The IR for α, β, and γ subunits was detected as numerous punctate staining within the cytoplasm, rather than on the membranes. However, the distribution pattern of all 3 subunits appeared unchanged in rabbits with either IAD or pregnancy, i.e., IR was found only in ductal cells and their intensities appeared unchanged.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

ENaC was a newly discovered class of ion channels that is located in the apical membrane of polarized epithelial cells, albeit no report in LG so far, mediating Na+ transport across the membranes,16,18–21,29,30 In this report, our RT-PCR data revealed the presence of mRNA for ENaCα and γ subunits in the rabbit LG. These results provide the first molecular evidence of ENaC subunits in rabbit LG. Immunofluorescence confirmed the presence of proteins of all three subunits in ducts, with most of the IR found within the cytoplasm. No IR was detected in acinar cells. These results appeared to be consistent with reports from salivary glands that showed α, β, and γ subunits in the membranes of the smaller striated and interlobular ducts.19,23 Western blot demonstrated the presence of α and γ subunits in LG. The presence of ENaC mRNA and protein in the LG suggests that they may play a similar role in salivary gland secretion.

While our data showed the mRNA level of γ was ~25 times that of α (Fig. 1), α subunit was found to be essential for Na+ reabsorption when independently expressed in Xenopuslaevis oocyte or rat thyroid cells, neither β nor γ subunits form functional Na+ channels when expressed alone but co-expression with α greatly enhanced Na+ current.31,32

In LG from rabbits with IAD, our results demonstrated that the levels of mRNA for both α and γ subunits were significantly decreased. Concordantly, Western blot showed significantly lower protein expression of both subunits as well. Rabbits with IAD demonstrated many of the dry eye symptoms and LG pathologies characteristic of Sjögren’s syndrome and has been used extensively to study the etiology of this debilitating disease.24–26 Decreased expression of these subunits at mRNA and protein levels may result in impaired Na+ re-absorption in LG ducts.

In LG from pregnant rabbits, protein expressions of α and γsubunits were significantly lower, albeit no difference was detected at mRNA level. These results suggest that the decreased expressions of ENaC may also play a role in the altered LG secretion during pregnancy. Our recent report showed that basal LG secretion from term pregnant rabbits were lower, while pilocarpine stimulated secretion was dramatically higher.33 These pregnant rabbits also demonstrated dry eye symptoms.27,28,33 Because dry eye is closely related to changes in sex hormone milieu in the body,34 substantial changes of the hormone profile during pregnancy may play a role in the occurrence of dry eye. Therefore, pregnancy has been proposed as a physiological model to study LG deficiency and dry eye.

Previous reports indicated that abnormality of ENaC activity may lead to numerous pathologies, i.e., hypertension.35 In chronic obstructive sialadenitis, elevated ENaC activity also played a role in the increase of saliva viscosity and Na+ concentration.36 Therefore, the decreased expression of ENaC subunits in LG of rabbit with IAD and pregnancy suggests reduced Na+ reabsorption into the ductal cells, resulting in increased Na+ content in the ductal lumen. ENaC may have an important role in the pathogenesis of dry eye, which may be caused by functional abnormalities of LG, i.e., progressive deterioration of its secretory capacity with smaller volumes of tear and increasingly higher Na+ concentration.

Saliva is secreted by the salivary glands in a two-stage process. Primary saliva are secreted by acini asNaCl-rich isotonic plasma-like fluid, and modified by the ductal cells while being transported in the duct system. Because the salivary ductal cells secrete K+ and HCO3−, reabsorb Na+ and Cl−, and are not permeable to H2O, the final saliva is hypotonic.37

However, the LG, while anatomically and functional very similar to salivary gland, has a final secretory product which is isotonic with significantly higher [K+] and [Cl−], as compared to the primary fluid.38–40 It has been shown that the presence of higher [K+] in the tears is beneficial to ocular surface health,5 although the role of higher [Cl−] is unclear.

To make [K+] and [Cl−] higher in the final LG fluid, there exist two possible scenarios: 1) ductal cells secrete K+ and Cl− into the lumen, resulting elevated [K+] and [Cl−]; 2) Na+ is reabsorbed into ductal cells, followed by reabsorption of H2O, therefore making [K+] and [Cl−] relatively higher in the final LG fluid.

Our previous results indicated that aquaporin 4 (AQP4) and aquaporin 5 (AQP5) were present in ductal cells,2,28 and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) were found predominantly in ducts.2,41,42 Aquaporins are membrane proteins responsible for fast water transport across plasma membranes, while CFTR functions as a Cl−-selective channel that mediates either influx or efflux, depending on the orientation of [Cl−]potential gradient. Findings that ENaC were found in ducts only appeared to suggest that the 2nd scenario maybe more likely in the LG. Our recent research showed CFTR expression was significantly decreased in LG of rabbit with IAD and pregnancy.41 It is not clear whether CFTR and ENaC function reciprocally in LG ductal cells, although it has been reported that ENaC and CFTR co-exist in the same salivary and sweat gland ductal cells with a functional interaction between these two channels resulting in coupled NaCl uptake.23,43,44 In freshly isolated normal sweat gland ducts, ENaC activity is also dependent on CFTR permeability.43 However, the decrease of these ENaC and CFTR that allow transepithelial NaCl absorption in LG duct suggest it may contribute to the higher[Na+] in the secreted tear, although direct functional studied are needed to provide definitive evidence.

It worth noting that there were apparent discrepancy between our RT-PCR and Western blot results, a phenomenon seen in our previous reports2,28,41,42 with other molecules45,46, and many other tissues/organs, with a number of possible explanations proposed, i.e., disruption in protein translation and post-translational modification, necessitating more studies, particularly the functional aspects of these molecules.

In summary, the present data demonstrated the presence of ENaC mRNA and protein expressions in the rabbit LG, suggesting it may play a role in LG secretion. Its significant change in rabbits with IAD and pregnant rabbits also suggests it may contribute to the altered LG secretions and ocular surface symptoms seen in these animals. However, mechanisms of how ENaC functions in the LG under physiological and pathological conditions certainly warrant further investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NEI/NIH grants EY017731 (ChuanqingDing), EY03040 (Doheny Eye Institute Core). The authors thank Austin Mircheff, Joel Schechter, Melvin Trousdale, Yanru Wang, Padmaja Thomas, Ruihua Wei, LeiliParsa, and Tamako Nakamura for their generous help, comments, and technical support.

Footnotes

Commercial Relationship: None

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Pflugfelder S, Tseng S, Sanabria O, Kell H, Garcia C, Felix C, Feuer W, Reis B. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tear-film disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 1998;17:38–56. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding C, Parsa L, Nandoskar P, et al. Duct system of the rabbit lacrimal gland: Structural characteristics and its role in lacrimal secretions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2960–2967. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mircheff A. Lacrimal fluid and electrolyte secretion: a review. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:607–617. doi: 10.3109/02713688908995761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dartt D, Moller M, Poulsen J. Lacrimal gland electrolyte and water secretion in the rabbit: localization and role of Na+/K+-activated ATPase. J Physiol. 1981;321:557–569. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp014002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ubels J, Hoffman H, Srikanth S, Resau J, Webb C. Gene expression in rat lacrimal gland duct cells collected using laser capture microdissection: evidence for K+ secretion by duct cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1876–1885. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tóth-Molnár E, Venglovecz V, Ozsvari B, Rakonczay Z, Jr, Varro A, Papp J, Toth A, Lonovics J, Takacs T, Ignath I, Ivanyi B, Hegyi P. New experimental method to study acid/base transporters and their regulation in lacrimal gland ductal epithelia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3746–3755. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mircheff A. Lacrimal fluid and electrolyte secretion: a review. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:607–617. doi: 10.3109/02713688908995761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dartt D, Moller M, Poulsen J. Lacrimal gland electrolyte and water secretion in the rabbit: localization and role of Na+/K+-activated ATPase. J Physiol. 1981;321:557–569. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp014002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herok GH, Millar TJ, Anderton PJ, Martin DK. Characterization of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel in the rabbit superior lacrimal gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herok GH, Millar TJ, Anderton PJ, Martin DK. Role of chloride channels in regulating the volume of acinar cells of the rabbit superior lacrimal gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5517–5525. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walcott B, Birzgalis A, Moore L, Brink P. Fluid secretion and the Na+, K+, 2Cl−cotransporter (NKCC1) in mouse exorbital lacrimal gland. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:C860–C867. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00526.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ubels J, Hoffman H, Srikanth S, Resau J, Webb C. Gene expression in rat lacrimal gland duct cells collected using laser capture microdissection: evidence for K+ secretion by duct cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1876–1885. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selvam S, Thomas P, Gukasyan H, Yu A, Stevenson D, Trousdale M, Mircheff AK, Schechter J, Smith R, Yiu S. Transepithelial bioelectrical properties of rabbit acinar cell monolayers on polyester membrane scaffolds. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1412–C1419. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00200.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez DAdl, Canessa CM, Fyfe GK, Zhang P. Structure and regulation of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:573–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook DI, Dinudom A, Komwatana P, Kumar S, Young JA. Patch-clamp studies on epithelial sodium channels in salivary duct cells. Cell BiochemBiophys. 2002;36:105–113. doi: 10.1385/cbb:36:2-3:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garty H, Palmer LG. Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:359–396. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.North RA. Families of ion channels with two hydrophobic segments. CurrOpin Cell Bio. 1996;8:474–483. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loffing J, Loffing-Cueni D, Macher A, Hebert SC, Olson B, Knepper MA, Rossier BC, Kaissling B. Localization of epithelial sodium channel and aquaporin-2 in rabbit kidney cortex. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278:F530–F539. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.4.F530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duc C, Farman N, Canessa CM, Bonvalet JP, Rossier BC. Cell-specific expression of epithelial sodium channel alpha, beta, and gamma subunits in aldosterone-responsive epithelia from the rat: localization by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(6 Pt 2):1907–1921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kretz O, Barbry P, Bock R, Lindemann B. Differential expression of RNA and protein of the three pore-forming subunits of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel in taste buds of the rat. J HistochemCytochem. 1999;47:51–64. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vuagniaux G, Vallet V, Jaeger NF, Pfister C, Bens M, Farman N, Courtois-Coutry N, Vandewalle A, Rossier BC, Hummler E. Activation of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel by the serine protease mCAP1 expressed in a mouse cortical collecting duct cell line. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:828–834. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasquez MM, Mustafa SB, Choudary A, Seidner SR, Castro R. Regulation of epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in the salivary cell line SMG-C6. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:522–531. doi: 10.3181/0806-RM-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catalan MA, Nakamoto T, Gonzalez-Begne M, Camden JM, Wall SM, Clarke LL, Melvin JE. Cftr and ENaC ion channels mediate NaCl absorption in the mouse submandibular gland. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 4):713–724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo Z, Song D, Azzarolo A. Autologous lacrimal-lymphoid mixed-cell reactions induce dacryoadenitis in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:23–31. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Z, Stevenson D, Schechter J. Lacrimal histopathology and ocular surface disease in a rabbit model of autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Cornea. 2003;22:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas P, Zhu Z, Selvam S, Stevenson D, Mircheff AK, Schechter JE, Trousdale MD. Autoimmune dacryoadenitis and keratoconjunctivitis induced in rabbits by subcutaneous injection of autologous lymphocytes activated ex vivo against lacrimal antigens. J Autoimmun. 2008;31:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding C, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Wong J, Yiu SC, Mircheff AK, Schechter JE. Pregnancy and the Lacrimal Gland: Where Have All the Hormones Gone? Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2005;46(Suppl) ARVO abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding C, Lu M, Huang J. Changes of the Ocular Surface and Aquaporins in the Lacrimal Glands of Rabbits During Pregnancy. Mol Vis. 2011;17:2847–2855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer LG, Corthesy-Theulaz I, Gaeggeler HP, Kraehenbuhl JP, Rossier B. Expression of epithelial Na channels in Xenopus oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1990;96:23–46. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matalon S, O'Brodovich H. Sodium channels in alveolar epithelial cells: molecular characterization, biophysical properties, and physiological significance. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:627–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature. 1994;367(6462):463–467. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snyder PM, Bucher DB, Olson DR. Gating induces a conformational change in the outer vestibule of ENaC. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:781–790. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding C, Chang N, Fong YC, Wang Y, Trousdale MD, Mircheff AK, Schechter JE. Interacting Influences of Pregnancy and Corneal Injury on Rabbit Lacrimal Gland Immunoarchitecture and Function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1368–1375. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan DA. Tearful relationships? Sex. hormones, the lacrimal gland, and aqueous-deficient dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2004;2:92–123. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bubien JK. Epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC), hormones, and hypertension. J Bio Chem. 2010;285:23527–23531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung J, Cho JG, Chae SW, Lee HM, Hwang SJ, Woo JS. Epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) expression in obstructive sialadenitis of the submandibular gland. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roussa E. Channels and transporters in salivary glands. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:263–287. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1089-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexander JH, van Lennep EW, Young JA. Water and electrolyte secretion by the exorbital lacrimal gland of the rat studied by micropuncture and catheterization techniques. Pflugers. Arch. 1972;337:299–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00586647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rismondo V, Osgood TB, Leering P, Hattenhauer MG, Ubels JL, Edelhauser HF. Electrolyte composition of lacrimal gland fluid and tears of normal and vitamin A-deficient rabbits. CLAO J. 1989;15:222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mircheff AK. Water and electrolyte secretion and fluid modification. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, editors. Principles and practice of ophthalmology. Chapter 29. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Publishing; 1994. pp. 466–472. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nandoskar P, Wang Y, Wei R, Liu Y, Zhao P, Lu M, Huang J, Thomas P, Trousdale MD, Ding C. Changes of chloride channels in the lacrimal glands of a rabbit model of Sjögren syndrome. Cornea. 2012;31:273–279. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182254b42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu M, Ding C. CFTR-mediated Cl(−) transport in the acinar and duct cells of rabbit lacrimal gland. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:671–677. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.675613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Functional interaction of CFTR and ENaC in sweat glands. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445:499–503. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0959-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinton PM. Role of epithelial HCO3-transport in much secretion: lessons from cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1222–C1233. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00362.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebrahimi M, Roudkenar MH, ImaniFooladi AA, Halabian R, Ghanei M, Kondo H, et al. Discrepancy between mRNA and Protein Expression of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Bronchial Epithelium Induced by Sulfur Mustard. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:823131. doi: 10.1155/2010/823131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu N, Drinnenberg I, Kelso J, Su J-R, Pä äbo S, Zeng R, et al. Comparison of protein and mRNA expression evolution in humans and chimpanzees. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]