Abstract

A 22-year-old male presented with 6 days history of intermittent fever with chills, 2 days history of upper abdomen pain, distension of abdomen, and decreased urine output. He was diagnosed to have Plasmodium vivax malaria, acute pancreatitis, ascites, and acute renal failure. These constellations of complications in P. vivax infection have never been reported in the past. The patient responded to intravenous chloroquine and supportive treatment. For renal failure, he required hemodialysis. Acute pancreatitis, ascites, and acute renal failure form an unusual combination in P. vivax infection.

KEY WORDS: Acute pancreatitis, malaria, Plasmodium vivax

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis is mostly caused by gallstone disease or alcoholism. Hypertriglyceridemia and certain drugs are also causative of acute pancreatitis. Infections are a rare cause of acute pancreatitis. Mostly, viral infections are associated with it. Of the parasitic diseases, Ascariasis, Toxoplasmosis, Clonorchis, and Falciparum malaria have been implicated to it.[1] A couple of report with pancreatitis associated with Plasmodium vivax malaria could be traced in the literature.[2,3] Both these patients expired. We here report another case of P. vivax infestation that developed acute pancreatitis, ascites, and acute renal failure and survived with treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old nonalcoholic male with 6 days history of intermittent fever with chills presented with 2 days history of upper abdomen pain radiating to back, reduced by sitting. The pain was associated with vomiting. His pulse rate was 134/min regular and of feeble volume, and blood pressure (BP) was 80/60 mmHg. The respiratory rate was 24 breaths/min and temperature was 36.7°C by axilla. The abdomen was distended with the presence of shifting dullness. Upper abdomen was tender. Heart sounds were feeble. There was reduced air entry bilaterally. His consciousness was intact and had no neurological deficit. There was reduced urine output. The patient had no history of similar episodes of abdominal pain in the past. There was no significant medical or surgical history in the past.

The investigations revealed hemoglobin 12.7 g/dL, (12–16), total leukocyte count 14,190/mm3 (4000–11,000) with differential leukocyte count of neutrophils 73%, lymphocytes 20%, and eosinophils 1%, and platelet count 159,000/mm3. Blood urea was 190 mg/dL (14–40), serum creatinine 4.27 mg/dL (0.5–1.2), serum Na+ 142 mEq/L (135–145), K+ 4.5 mEq/L (3.5–5.0), serum Ca2+ 8.8 mg/dL (8.5–10.2), and blood glucose 110 mg/dL (70–110). Serum bilirubin was 2.94 mg/dL (0.3–1.3) with direct 1.02 mg/dL (0.1–0.4), serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase 54 U/L (8–40 U/L) and serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase 99 U/L (10–38), alkaline phosphatase 125 U/L (13–100), and serum albumin 3.7 g/dL (3.5–5.5). The serum amylase was 1882 U/L (10–200), S. lipase 210 U/L (10–140), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 478 U/L. The coagulation profile showed bleeding time 1 min 30 s, clotting time 3 min, prothrombin time 13 s (control 13) INR 1, and activated partial thromboplastin time was 34.6 s (control 32.2). The lipid profile showed S. cholesterol 121 mg/dL, S. triglyceride 197 mg/dL, S. low-density lipoprotein 49 mg/dL, S. high-density lipoprotein 36 mg/dL. C-reactive protein level was 170 mg/dL (0–6).

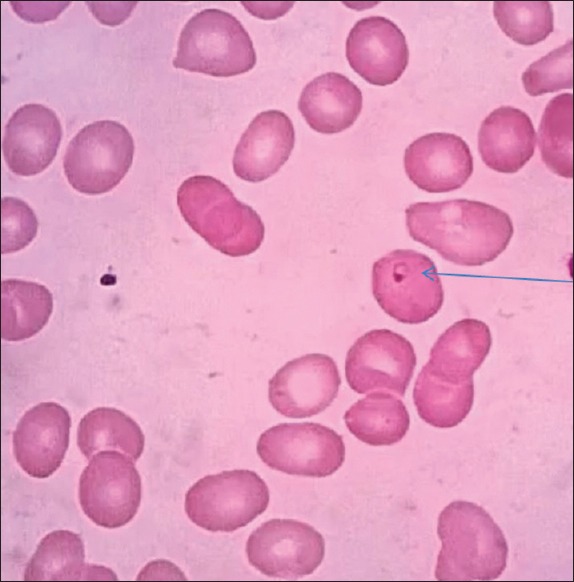

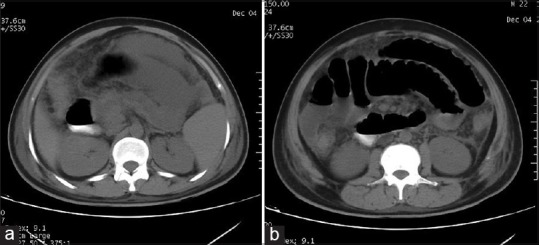

The peripheral blood film showed ring form of trophozoite of P. vivax [Figure 1]. The antigen testing including parasite LDH tested positive for P. vivax and negative for P. falciparum. The chest X-ray PA view and two-dimensional echocardiogram were normal. Ultrasonography of abdomen showed bulky pancreas, moderate ascites, and edematous both kidneys. There was no gallstone. A non contrast computerised tomography scan of the abdomen revealed finding suggestive of acute pancreatitis [Figure 2a and b]. Ascitic fluid examination was hemorrhagic and had protein 3.0 g/dL, sugar 110 g/dL, white blood cell 2200 mm3 with 83% neutrophils, 11% lymphocyte, 6% monocyte, and numerous red blood cell (RBC). The ascitic fluid amylase was 550 U/L. A diagnosis of P. vivax infection, acute pancreatitis, acute renal failure, and shock was made. The patient was put on intravenous chloroquine, inotropic support, and antibiotics. The BP normalized after 2 days of treatment. He tested negative for P. vivax after 3 days of treatment. After normalization of BP, he was put on hemodialysis. He improved over a period of next 4 weeks and was discharged. At the time of discharge, his blood urea was 56 mg/dL, S. creatinine 1.1 mg/dL, C-reactive protein was 4 mg/dL. Other investigations had normalized.

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood film showing trophozoite ring of Plasmodium vivax malaria

Figure 2.

(a) Plain computed tomography scan of abdomen showing pancreatic necrosis with peripancreatic fluid collection and fat stranding (b) Plain computed tomography abdomen showing lateral conal fascia thickening with fluid collection in peritoneum and fat stranding in mesentery

DISCUSSION

P. vivax infestation traditionally thought to be benign, off late, have been implicated to the development of severe complications. Most commonly defined severe complications with the vivax disease are severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic dysfunction, cerebral malaria, pulmonary syndrome, and renal failure. Pulmonary and renal complications have been the major cause of the death in P. vivax malaria. Of the atypical complications in P. vivax malaria rhabdomyolysis, immune thrombocytopenia, splenic hematoma, and rupture have been reported.[4,5,6] Acute pancreatitis has been added to this list of atypical complications.[2] We are reporting acute pancreatitis in a patient of P. vivax malaria who also developed ascites and renal failure.

Plasmodium falciparum is one parasite which has been associated with the development of pancreatitis.[7,8] The cause of it has been the capability of the organism to cause cytoadherence and sequestration leading to capillary thrombosis and pancreatitis, a phenomenon which is well defined.[9,10]

In P. vivax malaria, the mechanisms of development of severe diseases are not well defined. In vivo P. vivax infected RBCs are known to cause cytoadherence on human lining endothelial cells and placental tissue, though this phenomenon is lower than that with P. falciparum infected RBC.[4] Systemic inflammatory response is also increased in patient with severe P. vivax disease. There is an increase in the C-reactive protein, plasma tumor necrosis factor, and interferon-gamma levels the markers of inflammatory response. There is a linear trend in the increase in the inflammatory markers with the severity of disease. Inflammatory markers tend to go down with successful treatment of disease. In addition, interleukin 10 which is a down regulator of inflammatory response is reduced in severe P. vivax disease.[6] In our case, C-reactive protein normalized with successful treatment of the disease. It has also been said that the severity of vivax infection increased with the occurrence of chloroquine resistance.[11] However, our patient responded to chloroquine and hence chloroquine resistance cannot associated with severity of the disease. Chloroquine resistance severe vivax malaria has been reported in the past arguing against the association of severe vivax disease and chloroquine resistance.[12]

CONCLUSION

We are reporting a case of severe vivax malaria who developed acute pancreatitis, ascites, and renal failure and responded to treatment with chloroquine. This is probably the first survival case report of acute pancreatitis in vivax malaria.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenberger NJ, Conwell DL, Wu BU, Banks PA. Acute and chronic pancreatitis. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrisons Principle of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. pp. 2634–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma V, Sharma A, Aggarwal A, Bhardwaj G, Aggarwal S. Acute pancreatitis in a patient with vivax malaria. JOP. 2012;13:215–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atam V, Singh AS, Yathish BE, Das L. Acute pancreatitis and acute respiratory distress syndrome complicating Plasmodium vivax malaria. J Vector Borne Dis. 2013;50:151–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacerda MV, Mourão MP, Alexandre MA, Siqueira AM, Magalhães BM, Martinez-Espinosa FE, et al. Understanding the clinical spectrum of complicated Plasmodium vivax malaria: A systematic review on the contributions of the Brazilian literature. Malar J. 2012;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochar DK, Das A, Kochar SK, Saxena V, Sirohi P, Garg S, et al. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria: A report on serial cases from Bikaner in Northwestern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:194–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrade BB, Reis-Filho A, Souza-Neto SM, Clarêncio J, Camargo LM, Barral A, et al. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria exhibits marked inflammatory imbalance. Malar J. 2010;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seshadri P, Dev AV, Viggeswarpu S, Sathyendra S, Peter JV. Acute pancreatitis and subdural haematoma in a patient with severe falciparum malaria: Case report and review of literature. Malar J. 2008;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai DC, Gupta T, Sirsat RA, Shete M. Malarial pancreatitis: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:930–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Portillo HA, Lanzer M, Rodriguez-Malaga S, Zavala F, Fernandez-Becerra C. Variant genes and the spleen in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anstey NM, Handojo T, Pain MC, Kenangalem E, Tjitra E, Price RN, et al. Lung injury in vivax malaria: Pathophysiological evidence for pulmonary vascular sequestration and posttreatment alveolar-capillary inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:589–96. doi: 10.1086/510756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price RN, Douglas NM, Anstey NM. New developments in Plasmodium vivax malaria: Severe disease and the rise of chloroquine resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:430–5. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832f14c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexandre MA, Ferreira CO, Siqueira AM, Magalhães BL, Mourão MP, Lacerda MV, et al. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria, Brazilian Amazon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1611–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1610.100685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]