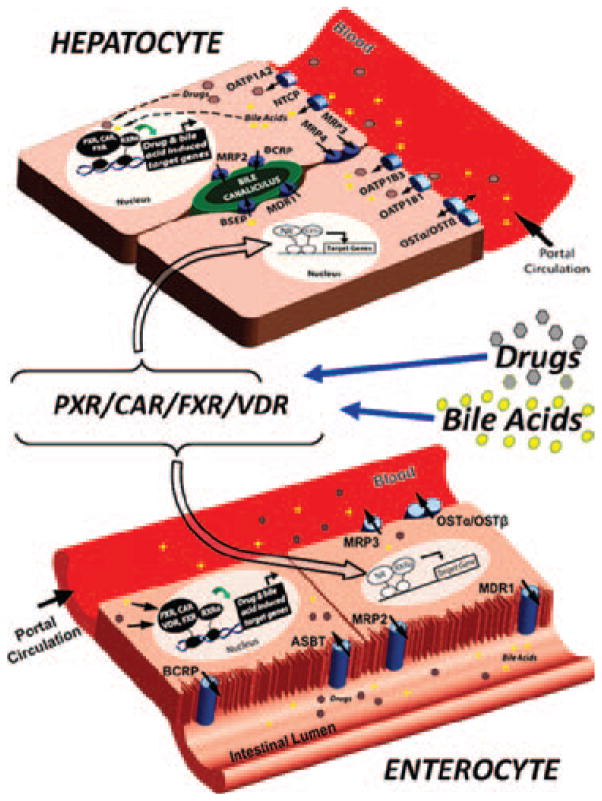

Figure 1.

NRs act as sensors in the regulation of enterohepatic drug transporters. Drugs and bile acids enter enterohepatic circulation by intestinal uptake transporters (e.g., ASBT). In many cases, these molecules are immediately transported back into the intestinal lumen by apical efflux transporters (e.g., MDR1, MRP2, and BCRP). Molecules that remain within the enterocyte can either serve as ligands to resident NRs, such as PXR, CAR, VDR, and FXR (bottom figure), or are effluxed into the portal circulation by sinusoidal efflux transporters (e.g., MRP3). After efflux to the portal vein, drugs and bile acids travel to the liver, where they are transported into hepatocytes by sinusoidal uptake transporters (e.g., OATPs and NTCP). Once inside hepatocytes, these molecules are either excreted into the bile canaliculus by canalicular efflux transporters (e.g., BSEP, MDR1, BCRP, and so forth) or serve as ligands to resident NRs, such as PXR, CAR, and FXR (top figure). Activation of these NRs in both the liver and intestine leads to their heterodimerization with RXRα. This NR/RXRα heterodimer, which is now bound to chromatin, initiates transcription of NR-specific target genes, including phase I and II drug-metabolizing enzymes as well as the drug transporters involved in uptake and efflux of NR-specific ligands (e.g., bile acids, drugs, and so forth). This drug-and bile-acid–induced regulation allows the enterohepatic system to maintain a homeostatic level of bile acids, drugs, and xenobiotics through feedback regulation that protects the body from potential toxic events.