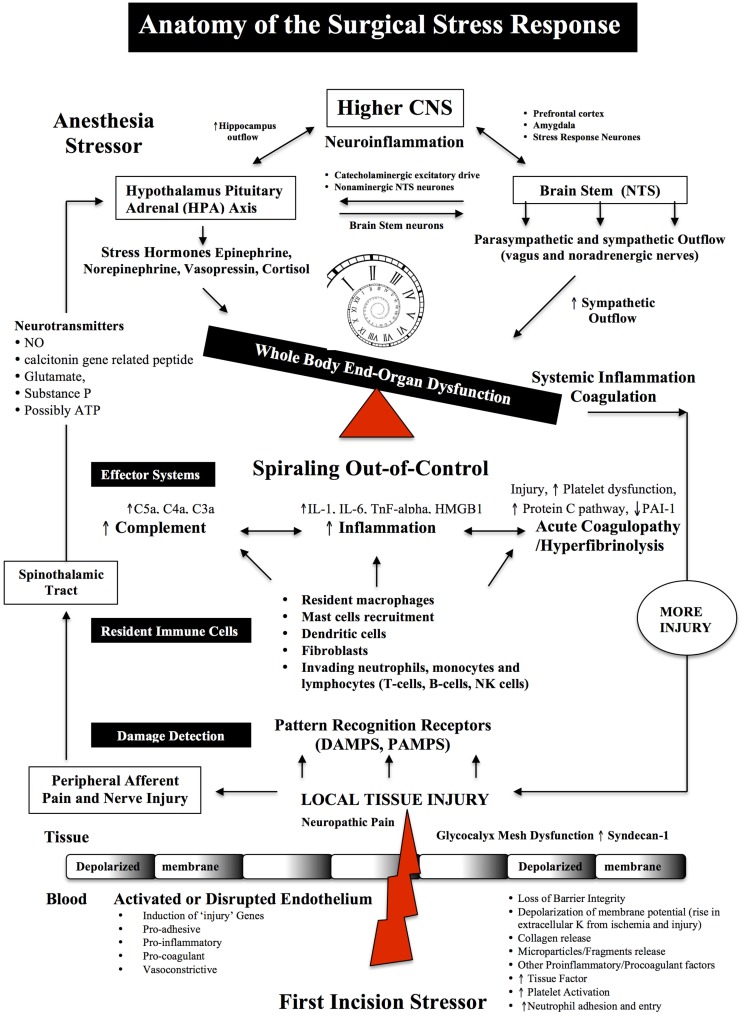

Figure 1.

Anatomy of the Surgical Stress Response. Surgical stress triggers a wide and varied response at multiple levels depending on the type and duration of surgery, anesthesia and the patient’s age, gender and prior health status. The early drivers of the stress response are sterile local injury, afferent nerve cell firing, activation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, Nucleus Tractus Solitarus (NTS), endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. Damage signals (also termed danger-associated molecular patterns or DAMPs and alarmins, e.g., heat shock proteins, adenosine, HMGB-1) are generated from tissue injury and detected by resident and non-resident immune cells. The key pro-inflammatory cytokines are IL-1, IL-6, and TnF-alpha and a complex interactions with complement. The primary goal of the acute immune response is wound healing and to prevent pathogen invasion. It is a restorative process that involves four phases: coagulation, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. Each phase of repair is predominately mediated by immune cells, cytokines, chemokines, transcription, and post-translational pathways (Tables 1 and 2). However, during major trauma, the early repair process can be overexpressed and lead to further injury, if not held in check. Peripheral nerve injury and pain induce afferent mediators and neurotransmitters to the spinal cord and central nervous system (CNS) and produce stress hormones, which exacerbate the stress response during major surgery.