Abstract

Classical theories of emotion have long debated the extent to which human emotion is a universal or culturally-constructed experience. Recent advances in emotion research in cultural neuroscience highlight several aspects of emotional generation and experience that are both phylogenetically conserved as well as constructed within human cultural contexts. This review highlights theories and methods from cultural neuroscience that examine how cultural and biological processes shape emotional generation, experience and regulation across multiple time scales. Recent advances in the neurobiological basis of culture-bound syndromes, such as Hwa-Byung (fire illness), provide further novel insights into emotion and mental health across cultures. Implications of emotion research in cultural neuroscience for population health disparities in psychopathology and global mental health will be discussed.

“Men ought to know that from the brain, and from the brain only, arise our pleasures, joys, laughter and jests, as well as our sorrows, pains, griefs and tears. …It is the same thing which makes us mad or delirious, inspires us with dread or fear, whether by night or by day, brings sleeplessness, inopportune mistakes, aimless anxieties, absentmindedness, and acts that are contrary to habit..” – Hippocrates

“Health is the greatest gift, contentment the greatest wealth.” - Buddha

The cornerstone of emotion in human life has been a central theme since the earliest scientific and religious writings of ancient Europe and Asia. Centuries before Darwinian theories of natural selection would largely guide modern emotion research, Hippocrates, a Greek physician, and Buddha, an Eastern religious teacher, observed that successful regulation of human emotion was key to maintaining a life of health and well-being. Divergent proclivities towards naturalistic or narrative explanations of human emotion were apparent in ancient scripts; Hippocrates traced the experience of human emotion to the body, and in particular, the human brain, as the central mechanism by which one could generate positive feelings, such as pleasure and joy, as well as regulate negative feelings, such as pain and sorrow. By contrast, through narrative and literary devices, such as metaphor, Buddha taught asceticism and compassion as emotion regulation strategies for reducing human suffering. Naturalistic and narrative accounts of emotion remain paramount in contemporary studies of human emotion, reflecting both the need and merit for multilevel explanation in affective science.

Classical theories of emotion are thought to comprise as a continuous spectrum of perspectives about what human emotion is, where it arises from, how it is generated and regulated (see Gross & Feldman-Barrett, 2011). On one end of the conceptual spectrum is the notion of basic emotion concepts, such as “fear”, “anger” and “happiness” that refer to a unique mental state arising from a unique mechanism and leading to a unique set of outcomes. In the strictest sense of a basic emotion account, emotions are modular, existing as distinct entities with discrete neural correlates and occurring automatically, possibly as a genetically inherited response (Mineka & Ohman, 2002). On the other end of the conceptual spectrum is the notion of the social construction of emotion, such that emotions are constructed within social interactions and environments (Mesquita & Frijda, 1992). The social construction view suggests that socially learned cultural scripts transmit the psychological features of emotion, such as when it is appropriate to feel an emotion, how to express it and the social significance or communicative function of an emotion.

Situated in between these dual concepts of basic emotion and social construction of emotion are cognitive appraisal and psychological construction theories. These two theories characterize the relative simplicity or complexity of psychological and neural networks necessary for emotion generation and regulation. Cognitive appraisal theories emphasize the meaning making or cognitive aspect of emotion, such that ways of thinking or interpreting the bodily manifestations of emotion, for instance, shape how emotion is generated and experienced. Psychological construction theories hold that emotions, as with all mental states, are byproducts of a continually modified constructive process that involves the coordinated interaction of multiple psychological and neural systems (Lindquist & Feldman-Barrett, 2012). Emotions may be either an emergent property from these interactions manifesting occurring as more than the sum of interactions or merely as a sum of the interactions of these systems.

Recent advances in cultural neuroscience suggest two main theoretical advances in emotion research. First, although historically developed as competing theories, the four classical theories of emotion (e.g., basic emotion, cognitive appraisal, psychological construction and social construction) are all, to a certain degree, simultaneously correct. That is, each theory of emotion characterizes features of processes of emotion generation and experience, but each at a different level of analysis, and all of which are important and necessary for adaptive emotional behavior to occur. Second, the four classical theories of emotion are largely represented in a dual inheritance or culture-gene coevolutionary theory of emotion. For instance, basic emotion and social construction of emotion theories represent the dual processes of genetic and cultural inheritance, while cognitive appraisal and psychological construction theories depict the refinement of cognitive and neural architecture that accompanies genetic and cultural selection of human emotional behavior.

This review aims to highlight the theoretical and empirical advances of emotion research in cultural neuroscience. Towards this goal, the following sections of this review provide an account of (a) dual inheritance or culture-gene coevolutionary (CGC) theories of emotion, (b) the cultural neuroscience framework used to test CGC theories of emotion, (c) empirical advances in cultural neuroscience demonstrating cultural influences on the emotional brain and (d) implications of cultural neuroscience research for closing the gap in population mental health disparities and achieving global mental health.

I. Culture-gene coevolutionary theories of emotion

Culture-gene coevolutionary theory

Darwinian evolutionary theories of emotion posit that emotional behavior provides a repertoire of adaptive behaviors that facilitate human survival (Barkow, Cosmides, Tooby, 1992; Darwin, 1872). Complementarily, culture-gene coevolutionary theory asserts that not only genetic, but also cultural selection, may occur in response to environmental or ecological pressures to produce a set of adaptive behaviors (Boyd & Richerson, 1985; Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman, 1981; Chudek & Henrich, 2011). Once cultural and genetic traits are adaptive, they further shape cognitive and neural architecture. Empirical investigations in cultural neuroscience are a viable way of testing culture-gene coevolutionary theories of human behavior (Chiao & Immordino-Yang, 2013).

Individualism-Collectivism and the Serotonin Transporter Gene (5-HTTLPR)

An early theoretical challenge in culture-gene coevolution was to identify viable coevolutionary models of human behavior. Given that cultural individualism and collectivism has been previously shown to shape cognitive (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Nisbett et al., 2001; Triandis, 1985), and more recently neural architecture (Chiao et al., 2009; Chiao et al., 2010; Harada, Li, Chiao, 2010), an initial hypothesis was that individualism-collectivism was a particularly viable candidate of a cultural trait in coevolutionary models of human behavior. Furthermore, Fincher, Schaller and colleagues (2008) showed that geographic variation in individualism-collectivism was related to geographic variation in historical and contemporary prevalence of infectious disease or pathogens. That is, collectivistic nations were more likely to have historical and contemporary prevalence of infectious diseases. By extension, if cultural collectivism was a selected cultural response to environmental pressure, then what gene underwent selection during the coevolutionary process?

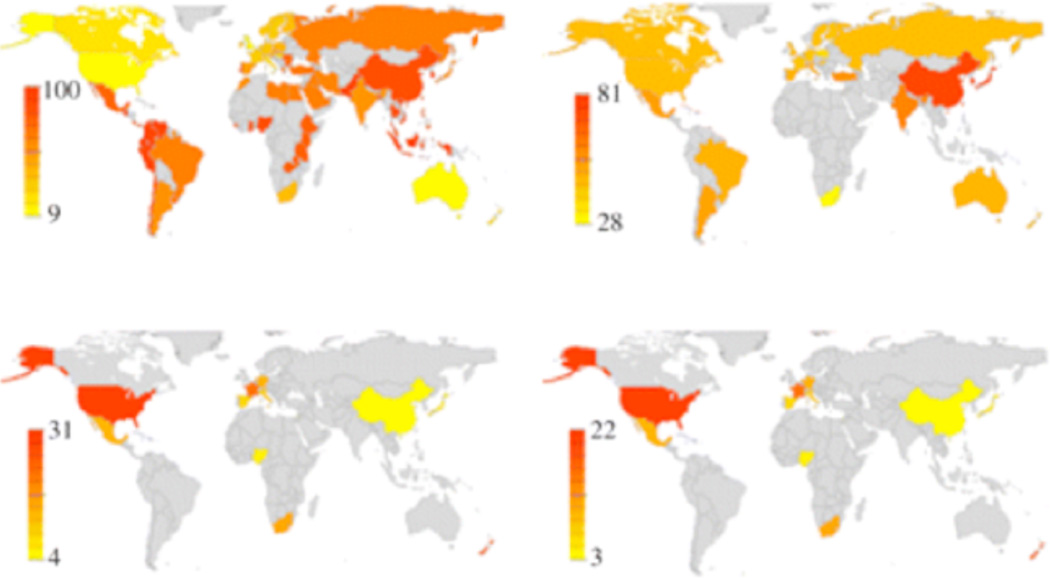

Chiao & Blizinsky (2010) found novel evidence that allelic variation of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) is correlated with cultural collectivism across nations (Figure 1). In geographic regions with heightened pathogen load, collectivistic cultural niches showed increased frequency of the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene. Surprisingly, despite an increased frequency of people with a genetic susceptibility for psychopathology, cultural collectivism across nations is associated with greater prevalence of mental health, including lower levels of anxiety and mood disorders across nations. Furthermore, this association between the frequency of the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene and increased prevalence of mental health is due in part to cultural collectivism. These findings identify for the first time a culture-gene coevolutionary model of human emotion and provide a testable theory of cultural differences in neural circuitry underlying emotion and psychopathology due to coevolution.

Figure 1. Culture-gene coevolutionary model of psychopathology (adapted from Chiao & Blizinsky, 2010).

(a) Geographical coincidence between serotonin transporter gene diversity, cultural traits of individualism–collectivism across countries, anxiety and mood disorders worldwide. Grey areas indicate geographical regions where no published data are available. Yellow to red colour bar indicates low to high prevalence.

Tightness-Looseness and the Serotonin Transporter Gene (5-HTTLPR)

Culture-gene coevolution of tightness-looseness and the serotonin transporter gene may serve as another example of how human emotion, particularly those related to moral attitudes, is a byproduct of cultural and biological factors. Tightness-looseness is a cultural dimension that refers to the sensitivity to social norms within a given cultural group (Gelfand et al., 2010). Tight cultures, such as Iran, Turkey and Singapore, maintain strict social norms and severe punishments for violations of social norms. On the other hand, loose cultures, such as the United States and United Kingdom, maintain flexibility in adherence to social norms allowing a wider range of social behaviors and fewer punishments for norm violators. Gelfand and colleagues (2010) recently showed that tightness-looseness across nations likely emerged in human history due to the presence of ecological threats, such as territorial disputes, environmental disasters among others. In geographic regions with a historical presence of ecological threats, cultural tightness may facilitate social survival for a majority of the population by ensuring strict adherence to norms or policies known to protect the group from these threats. By contrast, in geographic regions with little to no historical presence of ecological threats, cultural looseness may prove more advantageous for the group allowing for risk-taking and a tolerance for novelty and uncertainty amongst group members potentially increasing the probability of innovation and discovery.

Intriguingly, Mrazek and colleagues (2013) demonstrated that cultural tightness-looseness emerged from ecological threat due in part to genetic selection of the serotonin transporter gene. Tight nations have an increased prevalence of people who carry the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene. Furthermore, cultural tightness-looseness predicts moral justifiability or moral attitudes to a host of behaviors due in part to allelic variation of the serotonin transporter gene (Figure 2). Hence, geographic variability in moral attitudes towards controversial issues, such as euthanasia, abortion, suicide, divorce and tax evasion, is due to both cultural and genetic selection. Future cultural neuroscience research is needed to determine how cultural and genetic factors regulate how people feel about major social and political issues. For instance, can dynamic changes in cultural priming or genetic expression shift moral attitudes? Can cultural change due to economic and technological growth catalyze biological changes in moral attitudes across generations? By testing culture-gene coevolutionary theories of emotion with a cultural neuroscience approach, we gain greater insight into the mechanisms and origins of diversity in human emotional life.

Figure 2. Culture-gene coevolutionary model of morality (adapted from Mrazek et al., 2013).

(a) Cultural tightness-looseness positively correlates with allelic frequency of the serotonin transporter gene and moral attitudes across nations; (b) Allelic variation of the serotonin transporter gene predicts moral attitudes across nations due to cultural variation in tightness-looseness.

II. What is cultural neuroscience?

Cultural neuroscience is an interdisciplinary field that examines how cultural and biological mechanisms mutually shape human behavior across phylogenetic, developmental and situational timescales (Chiao & Ambady, 2007; Chiao, Cheon, Pornpattananangkul, Blizinsky, Mrazek, 2013; Cheon, Mrazek, Pornpattananangkul, Blizinsky, Chiao, 2013). Over a decade of conceptual and empirical progress in cultural neuroscience has demonstrated the viability of this approach. Park & Gutchess (2002) introduced the concept of a ‘cultural neuroscience of aging’ to describe how cultural competencies may provide an important cognitive buffer in older age due to the cognitive decline and neurodegeneration that accompanies later life. Chiao & Ambady (2007) developed a framework for cultural neuroscience that involves integrating theory and methods from cultural psychology, neuroscience and population genetics. Han & Northoff (2008) introduced ‘transcultural neuroimaging’ as an approach for indirectly measuring neural activity in people of Western and Eastern descent with neuroimaging and event-related potentials. Vogeley & Roepstorff (2009) discussed the notion of ‘looping effects’ that arise due to the dynamic nature of culture-biology interactions. Ambady & Bharucha (2009) suggested ‘cultural mapping’ and ‘source analysis’ as tools for discovering what kinds of cognitive functions vary across cultural contexts and why. Finally, Kitayama & Uskul (2011) developed a ‘neuro-culture interaction model’ to explain ‘culturally-patterned neural activities’ that emerge due to neuroplasticity or neuronal changes across development that facilitate social survival. Theory and methods in cultural neuroscience integrate concepts and tools from cultural science, neuroscience and population genetics (Chiao et al, 2010). Study designs that integrate theory and methods from these disciplines provide a keen vantage point for investigating the cultural and biological mechanisms of human emotion.

III. Emotion in cultural neuroscience

Culture-gene coevolutionary models of human behavior provide a rich theoretical basis for the study of human emotion (Figure 3). By identifying the cultural and genetic traits that have coevolved in response to environmental or ecological demands, these models provide a rationale for empirical investigations in cultural neuroscience that test the specificity and magnitude of cultural and genetic influences on neural and physiological pathways of emotion and behavior. Cultural influences on the human brain may also arise due to non-coevolutionary related factors, such as neuroplasticity and top-down modulation of subcortical structures. Throughout human development, synaptic connections across brain regions are both pruned and reinforced based on presence or absence of environmental input. Brain regions may show further modulation by cultural context due to a number of top-down factors (Hofstede, 2002; Markus & Kitayama, 1991), including the goal orientation (Lee, Aaker, Gardner, 2000) and motivational styles transmitted from cultural norms, practices and beliefs (Markus & Kitayama, 1991).

Figure 3. Cultural neuroscience model of emotional behavior.

(adapted from Chiao & Immordino-Yang, 2013; Chiao & Blizinsky, in press)

A. Emotion recognition

Culture and fear

Early investigations into the cultural influences on neural pathways of emotion were initially motivated by a long history of debate in culture and emotion behavioral research concerning universality and cultural specificity in emotion recognition (Ekman, 1972, 1994; Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Izard, 1971; Matsumoto, 1989; Russell, 1994; Scherer & Wallbott, 1994). The capacity to perceive and recognition emotion across cultures is necessary for successful social interaction and survival. Given the salience of cultural group members for providing survival strategies and support throughout development, it is possible that processing in human amygdala tunes to social input from group members to a greater extent compared to that of other group members. People can infer nationality from facial expressions of emotion (Marsh, Elfenbein, Ambady, 2003) as well as recognize emotions expressed by cultural group members better than those of other group members (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

Initial neuropsychological evidence into the neural basis of emotion recognition highlighted the importance of the human amygdala in fear recognition (Adolphs et al., 1994). Patients with bilateral amygdala damage showed focal impairment in recognizing fear from the face (Adolphs et al., 1994), which was later shown to be due to the lack of attentional orientation towards the critical facial features that express fear (Adolphs et al., 2005). When instructed to look at the eye region of the fear facial expression, bilateral amygdala damage patients demonstrate intact emotion recognition performance highlighting the role of the amygdala in orienting attention towards salient aspects of an emotional scene, rather than storing representations of discrete emotions per se.

Convergent evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology show that the amygdala is a subcortical brain structure implicated in emotion processing such as fear recognition, resolving ambiguity in the environment and uncertainty (Pessoa & Adolphs, 2010; Whalen, 2007). The human amygdala was proposed an early candidate of a distinct neural module of fear (Mineka & Ohman, 2002), with approximately 10% of activity within this brain region regulated by a specific gene, the serotonin transporter polymorphism, in humans (Hariri et al., 2002; Munafo, Brown, Hariri, 2008). While genetic inheritance plays a role in amygdala function, little was known about the role of cultural inheritance on amygdala function until recently. Chiao and colleagues (2008) first showed that the human amygdala responds preferentially to fear faces when expressed by members of one’s own cultural group compared to those of another cultural group (Figure 4). Both Caucasian-Americans living in the US and Native Japanese living in Japan showed increased bilateral amygdala response to fear faces, but not angry, happy or neutral faces, when recognizing emotion from the face. Enhanced vigilance towards fear expressed by group members may prove adaptive given the physical and psychological proximity of group members to the self, thus increasing the probability for perceived or actual threat contagion across group members compared to non-group members.

Figure 4. Cultural influences on amygdala response to fear faces (adapted from Chiao et al., 2008).

(a) Bilateral amygdala response to emotional faces.

Cultural proximity is not always predicted by group membership, such as nationality, particularly in the case of immigrants who choose to live geographically distant from their heritage culture. Immigrants face a host of psychological challenges when attempting to integrate beliefs, norms and practices of their heritage and host culture (Berry, 1997). The degree to which individuals acculturate, defined by the adaptive integration of attitudes about one’s heritage and host culture, may play a key role in the extent to which the amygdala tunes to the emotional facial cues expressed by group members.

Berry’s (1997) U-shaped theory of acculturation posited that psychological adjustment to the host culture follows a non-linear or U-shaped path. Initially, immigrants show positive feelings towards the host culture and experience a ‘honeymoon’ period or a time of psychological well-being followed by a ‘crash’ period when acculturative stress due to adjustments or negotiations between the heritage and host culture is encountered. Acculturative stress may lessen with time as psychological well-being is recovered with subsequent time and experience in the host culture garnering of psychological resources for coping. Supporting this view, Derntl and colleagues (2009) recently showed an inverse relation between amygdala activation to emotional faces and degree of acculturation for Asians living in Europe. Asians who spent less time in Europe showed stronger amygdala response to emotional faces suggesting that increased amygdala reactivity reflects heightened novelty or vigilance to emotional cues in recent immigrants. Notably, these findings also demonstrate the flexibility of subcortical responses to emotion as those with more time spent in the host culture showed less amygdala response to emotional cues. For immigrants, the fluctuations in emotional experience caused by cultural change or acculturation may not only manifest in subjective feelings, but also in neurobiological circuitry of emotion responsible for the maintenance and regulation of psychological well-being. Further investigations of the neurobiological basis of acculturation or cultural change may prove fruitful for demonstrating the neural and physiological costs and benefits of acculturation for immigrant health.

C. Emotional experience

Evident in early Western and Eastern moral philosophy, culture codes of ethical or moral behavior distinguish between a life spent in pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain and suffering. For Eastern philosophical traditions, such as Buddhism and Hinduism, the pursuit of pleasure is a key antecedent to the experience of pain. On the other hand, various schools of Western thought, including hedonism and utilitarianism, have argued for the moral virtue of a life in pursuit of pleasure. For hedonists, to live a good life is to pursue the maximal pleasure possible, similarly for utilitarian ethicists, a moral life is one that both maximizes pleasure and minimizes suffering

Cultural values and norms may define not only the absolute or relative virtue of pleasure or pain, but also what behavioral antecedents constitute pursuit of pleasure or pain, respectively. For collectivistic cultures, freedom of expression represents a societal vice but conformity a social virtue, whereas for individualistic cultures, freedom of expression is a societal virtue and its suppression a social vice. Similarly, for tight cultures, observance of social deviance represents a form of social pain whereas for loose cultures, nonconformity or uniqueness from others may constitute a social pleasure, behavior that elicits social admiration and a desire to bond from others. This cultural divergence in what kinds of social behaviors constitute pleasure or pain for others underscores the key role of social learning in the transmission of cultural norms (Chudek & Henrich, 2011) and heuristics for maintaining health and psychological well-being in one’s self and others.

Culture and reward

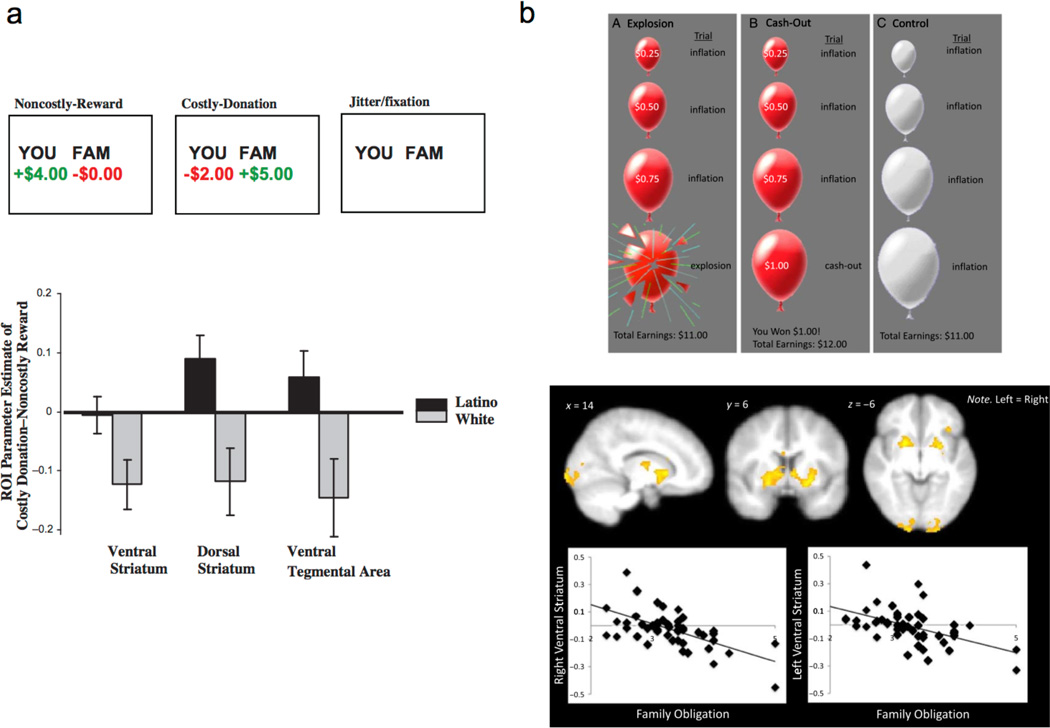

Family obligation in Latino culture refers to a set of cultural expectations that alter the subjective experience of reward (Fuligni, 2001; Cuellar, Arnold, & Gonzalez, 1995). Family obligation may involve helping other family members, even at a cost to one’s self in a manner consistent with collectivistic cultural norms. For family members in Latino communities that often endorse collectivistic cultural norms, the gains of others may be experienced similarly as gains for one’s self, due to the overlap of self and other representation (Telzer et al, 2010). Telzer and colleagues (2010) recently found that whereas Caucasian-Americans show increased mesolimbic response when receiving a reward to themselves; remarkably, Latinos showed greater activity in neural reward regions during costly donation to family, rather than reward to the self. In a subsequent study, Telzer and colleagues (2013) further showed that activity in the ventral striatum to monetary reward is negatively related to family obligation engendering a lower risk preference in adolescents (Figure 5). Latino adolescents who value obligations to family show greater risk aversion and lower neural sensitivity to increasing rewards. When raised in a cultural community that emphasizes social harmony with others, Latino adolescents may find monetary rewards less rewarding than social bonds with close others.

Figure 5. Family obligation in Latino adolescents modulates ventral striatum activity to monetary (a) reward and (b) risk (adapted from Telzer et al., 2010 and Telzer et al., 2013).

The value of reward may also be affected by the amount of time it takes to receive a reward (McClure, Laibson, Loewenstein, Cohen, 2004) and the cultural dimension of long-term and short-term orientation (Hofstede, 2001). Cultures with a long-term orientation, such as Korea, foster virtues oriented towards future rewards, including perseverance and thriftiness. By contrast, cultures with a short-term orientation, such as the United States, are more likely to foster virtues oriented towards the past and present rewards, such as immediate results and spending. Intertemporal choice or delay discounting captures the psychological value of reward as a function of time. When people prefer rewards sooner rather than later, they exhibit delay discounting whereby a reward is devalued due to the expected delay in receipt. Consistent with Hofstede’s cultural dimension of long-term and short-term orientation, Kim, Sung and McClure (2012) recently found that Americans show greater delay discounting of financial rewards and stronger ventral striatum response to immediate rewards compared to Koreans. Furthermore, rewards elicited greater ventral striatum response in Koreans when presented with delay, indicating correspondence between the neural and cultural valuation of reward. When people from a short-term orientation culture are presented with monetary rewards, the ventral striatum shows increased response likely to facilitate adherence to experiencing gain in the present. By contrast, when people from a culture of long-term orientation are shown monetary rewards, the physiological response to reward is muted, and possibly less adaptive due to the lack of cultural emphasis on experiencing gain in the immediate context, but instead behaving in ways that anticipate rewards in the future.

Culture and pain

The human desire to avoid pain and suffering may appear largely universal, but the processes by which people experience and alleviate pain and suffering may be culturally distinct. Empathy is a social process of sharing feelings with others and triggered when observing pain in others (Preston & deWaal, 2002). The visceral or cognitive understanding of a painful experience in others is a precursor to altruism or helping behavior that marshals psychological, social and material resources to alleviate the pain and suffering other others. A distinct neural network of brain regions has been reliably shown to active when perceiving and responding to the pain of others, including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and bilateral insula (AI) (Lindquist et al, 2012).

Cultural modulation of neural correlates of pain and empathy may be due to a number of factors (Chiao & Mathur, 2010). Social factors, such as historical conflicts between groups whereby one social group has been systematically marginalized or oppressed by another, produce robust differences in the magnitude and extent to which certain social groups have experienced physical, emotional and social pain due to racial oppression (Williams et al., 1997). Biological factors, including the increased genetic susceptibility to pain-related disease such as sickle cell disease in Africans and African-Americans, may further affect the prevalence of acute and chronic pain experience across racial and ethnic group (Kwiatkowski, 2005). As a consequence of social and biological factors, racial or ethnic differences in sensitivity or tolerance to pain may emerge and persist across generations. African-Americans demonstrate lower pain tolerance (Rahim-Williams, Riley, Williams, Filingham, 2013) compared to non-Hispanic Whites, as well greater severity of clinical pain and pain-related disability (Edwards et al., 2001; Green et al., 2003). The cultural transmission of negative stereotypes and attitudes of historically oppressed minorities may further exacerbate the extent to which minorities suffer from pain as well as inequity in access to appropriate health care for acute and chronic pain.

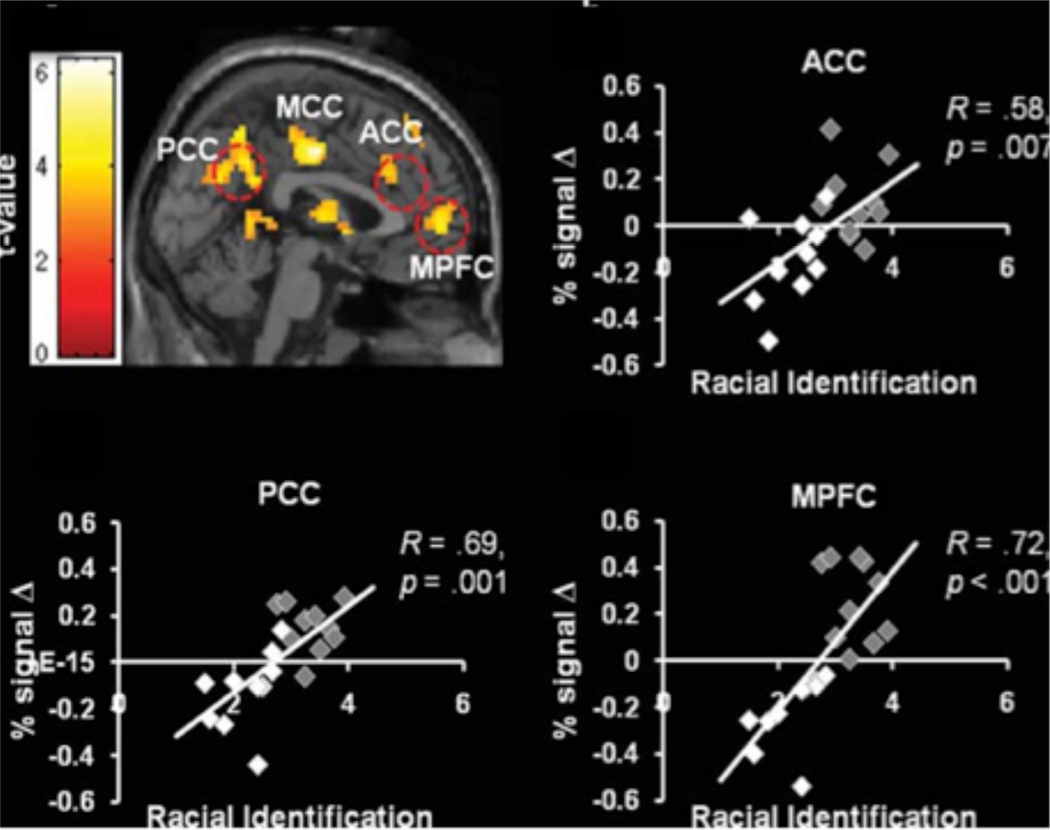

Cultural group membership has been shown to modulate a subset of neural circuitry for pain perception, such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Both Chinese and European participants show increased ACC response to pain perceived in members of their own cultural group (Xu et al., 2009). Cultural attitudes and identity also shape how people respond to the pain of others, such as feelings of empathy and motivation for altruism (Avenanti et al., 2010; Cheon et al., 2011/2013; de Greck et al., 2012; Mathur, Harada, Chiao, 2012). Mathur and colleagues (2012) showed that ethnic identity, or the extent to which a person identifies with their ethnic group, modulates cortical midline and medial temporal lobe response when empathizing with the emotional pain of group members in African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans (Figure 6). African-Americans who show high identification with their ethnic group demonstrate increased cortical midline response during empathy for pain of group members, whereas Caucasian-Americans who show low identification exhibit increased neural response within medial temporal lobe regions, such as bilateral parahippocampal gyrus when empathizing to the pain with group members. These findings suggest that distinct neural pathways subserve the capacity to share the pain of others within one’s cultural group due to ethnic identification. When the psychological distance between self and others within one’s group is small, people rely in neural circuitry associated with thinking about other people, including perspective-taking and affect sharing, but when psychological distance is large, people instead rely on neural circuitry associated with learning, such as encoding and retrieval.

Figure 6.

Ethnic identification modulates empathic neural response for group members (Mathur, Harada, Chiao, 2012); Grey diamonds = African-American and White diamonds = Caucasian-American

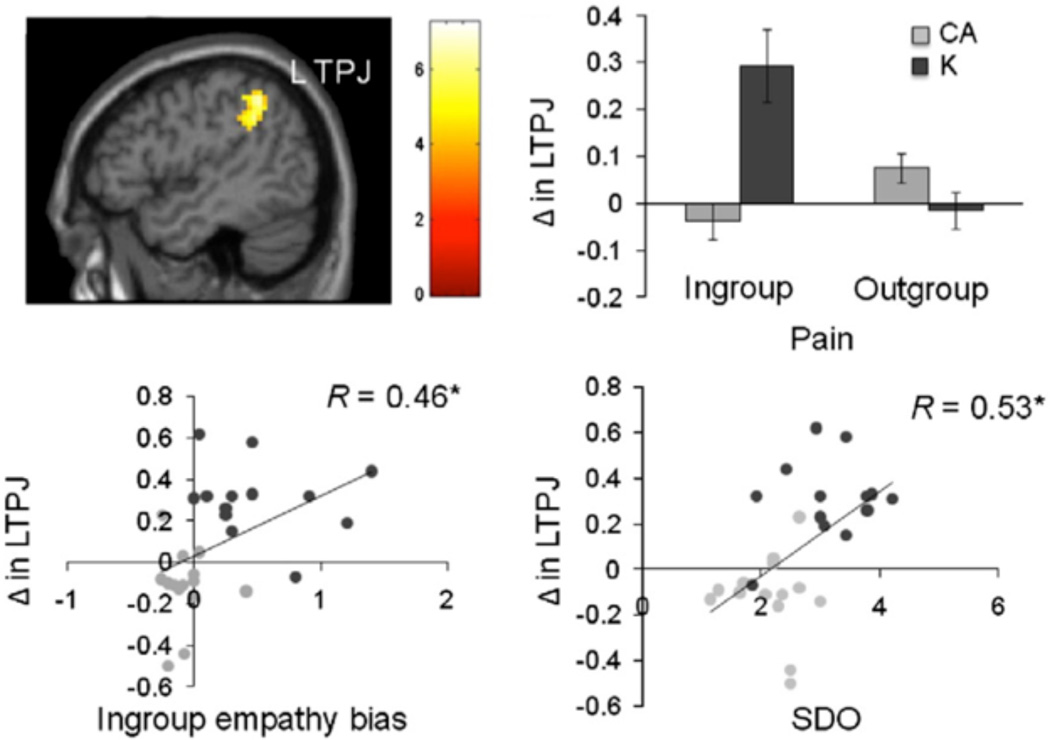

Preference for social hierarchy also affects how people respond to the pain of group members. Cheon and colleagues (2011) recently found that social dominance orientation, or preference for social hierarchy, predicts empathy for pain of ingroup members due to increased response within the left temporoparietal junction (L-TPJ) in Koreans and Caucasian-Americans (Figure 7). The temporoparietal junction has previously been implicated in theory of mind or knowledge representations about the thoughts, beliefs and feelings of other people. Koreans who live in hierarchy-preferring culture may recruit L-TPJ to a greater extent compared to Caucasian-Americans because theory of mind may prove a more effective way of understanding the pain of other Koreans. By contrast, Caucasian-Americans may rely more on simulation as a social cognitive route to empathizing with the pain of other group members (Mathur et al., 2010).

Figure 7.

Cultural influences on intergroup empathy (adapted from Cheon et al., 2011); Dark circles = Koreans and Grey circles = Caucasian-Americans

D. Emotion regulation

Cultural display rules provide a set of social norms concerning when it is appropriate to express emotion, to whom and to what extent (Ekman & Friesen, 1969; Matsumoto et al, 2009). Display rules may serve to guide social interactions in a manner that conforms to cultural expectations or values. Cultural scripts about what kinds of emotions are appropriate in a given social context are important for guiding individuals about when in social situations it is important to regulate their emotions, either by suppression or cognitive reappraisal in order to avoid displaying an inappropriate emotion (Gross & John, 2003; Matsumoto et al., 2008; Tsai & Levenson, 1997). For instance, men in Japan may suppress or reappraise feelings of sadness when hearing the loss of a loved one in order to conform to their dominant social role, whereas women in Japan may suppress or reappraise feelings of contempt when witnessing a moral violation in conformity with their submissive social role. Given the particular importance of display rules and steadfast reliance on emotion regulation in collectivistic cultures, it is possible that culture may differentially affect neural circuitry of emotion regulation.

Culture and emotion suppression

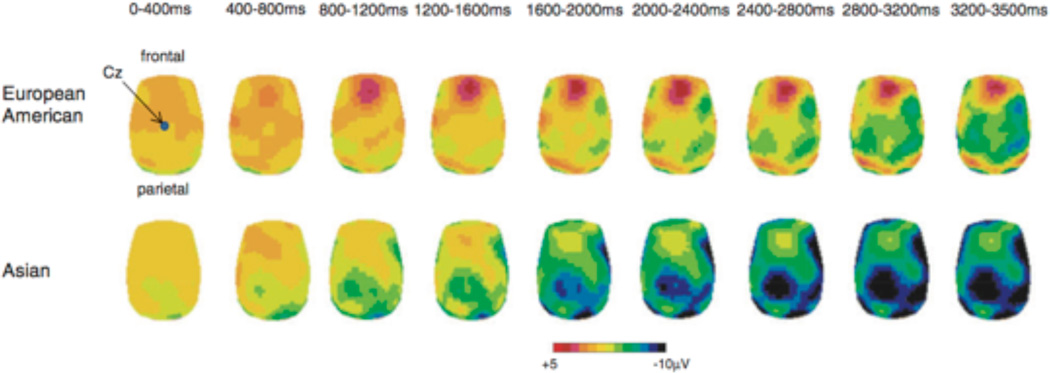

The cultural emphasis on suppressing emotional expressions when interacting with others particularly within collectivistic cultures may alter biological processes recruited during emotion regulation (Murata et al., 2013, Figure 8). Testing this hypothesis, Murata and colleagues (2013) measured electrophysiological responses in East Asians and European Americans while suppressing their emotions highly arousing and unpleasant emotional pictures. Results from the late positive potential (LPP), waveform recorded from the midline parietal electrode that reflects enhanced perceptual processing of emotional stimuli in visual cortices resulting from feedback from the amygdala, showed reduced response during suppression compared to when attending in Asian, but not European American participants. These neural findings suggest that for Asians, but not European Americans, emotion suppression is an effective strategy for dampening or reducing emotional experience during regulation.

Figure 8. Cultural influences on neural basis of emotion regulation (adapted from Murata, Moser, Kitayama, 2010).

(a) Topographical maps of electrophysiological response during emotion suppression. Asians show reduced LPP during emotion suppression compared to attend conditions as well as European-Americans during attend and suppress conditions.

Biological mechanisms, such as genetic factors that regulate socio-emotional sensitivity, may also affect the frequency or habitual use of emotion regulation strategies when navigating social interactions across cultural contexts (Kim & Sasaki, 2012). The oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) rs53576 has previously been associated with social sensitivity. Compared to people who carry the A allele, people who carry the G allele of OXTR are more likely to exhibit sensitive parenting behavior (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2008), empathic accuracy (Rodrigues et al., 2009) as well as optimism and self esteem (Saphire-Bernstein et al., 2011). Kim and colleagues (2011) recently found that across cultures, people who are genetically disposed to greater socio-emotional sensitivity, that is those who carry two copies of the G allele, showed culturally-congruent patterns of emotion regulation. Consistent with cultural norms, G allele carriers in American showed less habitual use of emotional suppression, whereas G allele carriers in Korea showed greater habitual use of emotional suppression. These results demonstrate a novel gene-culture interaction in emotion regulation use and the importance of cultural context on gene-behavior associations. Depending on the norms and practices of a given culture, people with the same genes may adopt differential repertoires of behavior in order to display social sensitivity in an adaptive manner.

Culture and compassion

Cultural practices, such as meditation performed in contemplative traditions, teach verbal strategies for cultivating feelings of compassion towards self and others (Lutz et al., 2008). Compassion meditation differs from other kinds of emotion regulation strategies, such as emotion suppression or cognitive reappraisal (Lutz et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013). Whereas reappraisal regulation strategies involve rethinking the meaning or significance of an emotional event, compassionate meditation involves focusing on feelings of compassion for others while thinking of compassion-related verbal phrases (Wang et al., 2013). Meditation training of compassion may serve to up-regulate one’s emotions, including positive feelings towards those who are suffering (Hutcherson, Seppala, Gross, 2008), which can lead to increases in prosocial behavior (Klimecki, Leiberg, Ricard, Singer, 2013), empathic accuracy (Mascaro et al., 2013) as well as improvements in psychological and physical health (Fredrickson et al., 2008). Recent neuroimaging studies of compassion experts and novices show that cultural practices such as meditation training are effective at modulating neurobiological mechanisms of emotion, including the amygdala and insular cortices (Desbordes et al., 2012; Immordino-Yang, McColl, Damasio, Damasio, 2009; Lutz et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013), and produce divergent neural effects compared to cognitive reappraisal regulation strategies (Wang et al., 2013). These findings demonstrate that top-down modulation of responses within neural circuitry during practice of compassionate meditation may provide a distinct approach to emotion regulation, conferring psychological and health benefits as well as enhancing prosocial behavior.

E. Emotion and psychopathology

Culture-bound syndromes

Experiences of mental health and illness are perceptible across all cultures, however, how these emotional experiences are perceived, experienced and regulated when awry, may be constrained by the local and cultural communities in which such experiences manifest. Medical anthropologists and cultural psychiatrists have long noted that mental illness may manifest in distinctive forms across cultural contexts as culture-bound syndromes. Culture-bound syndromes refer to patterns of aberrant behavior that occur within a local context and may have similar and distinct features from other non-culture bound syndromes (Guarnaccia & Rogler, 1999; Mezznich, Kleinman, Fabrega, Parron, 1996). The fourth edition of the Diagnostic Structural Manual (DSM-IV) provided for the first time a glossary of the symptoms associated with 25 culture-bound syndromes, including amok, latah and koro (Mezznich, Kleinman, Fabrega, Parron, 1996). The utility of culture-bound syndromes as a concept within cultural psychiatry and medical anthropology is apparent when treating patients from communities of color. Culture-bound syndromes can be recognized not only within the medical, but also ways within the cultural community of describing symptoms such as feelings or behaviors typically associated with mental illness.

Hwabyung (HB) is Korean culture-bound syndrome that describes a feeling of anger at being a victim to chronic social aggression (Min, 2009). Patients with HB report increased suppression of anger in interpersonal relations in order to maintain social harmony despite a perception of bullying or interpersonal harm. In particular, feelings of anger and injustice or unfairness characterize HB, which can involve behavioral symptoms such as sighing, tearing, talkativeness and approaching open spaces. Bodily symptoms of HB may include heat sensations or an intolerance to heat as well as chest compression, heart palpitations and respiratory stuffiness among others. Epidemiological evidence suggests approximately 4.95% of elderly Korean women are afflicted with Hwabyung, suggesting that only a specific demographic within the culture experiences this culture-bound syndrome.

Due to the heightened sensitivity to the feeling of anger associated with HB, one possibility is that neural circuitry associated with the perception and generation of anger may show dysregulation or heightened activity in HB patients compared to healthy controls. In a first study to examine the neurobiological basis of culture-bound syndrome, Lee and colleagues (2009) measured neural response in HB patients and healthy controls while they passively perceived neutral, angry and sad faces (Figure 9). HB patients and health controls differed in their subjective ratings of sad faces such that healthy controls perceived greater arousal in sad faces compared to HB patients. Several brain regions showed differences in response to emotional faces between the two groups. HB patients showed heightened response in perceptual regions of the brain, including fusiform and lingual gyri compared to healthy controls, possibly due to increased perceptual processing of emotional faces in those afflicted with this culture-bound syndrome. Furthermore, HB patients showed less response within the right ACC compared to healthy controls to neutral faces, suggesting that the neurobiological basis of HB may be due to dysregulation of ACC and heightened sensitivity within ventral visual cortex to emotion cues. The relation between severity of HB or HB symptomology and neural response to emotion was not examined in the prior study.

Figure 9. Neural basis of culture-bound syndrome ‘Hwa-Byung’ (fire illness) (adapted from Lee et al., 2009).

(a) Features of the experimental design. (b) Compared to healthy controls, HB patients show increased neural response in ventral visual pathway when passively viewing emotional faces.

Future neuroscience research of culture-bound syndromes may investigate more directly the relation between disease severity and affective neural response as well as the relative contribution of cultural and genetic factors in the modulation of affective neural circuitry in culture-bound syndrome patients compared to healthy controls. Research in cultural neuroscience of culture-bound syndrome and related phenomena may provide much needed objective measures or characterizations of biological mechanisms associated with sets of symptomology of disease, that have been previously been considered highly subjective and even culturally constructed phenomena (Seligman & Kirmayer, 2008; Seligman & Brown, 2010).

IV. Implications for population disparities and global mental health

More than a decade ago, the World Health Organization in 2001, highlighted mental, neurological and substance abuse (MNS) disorders as a source of tremendous financial and social burden globally with approximately 25% of all disability due to MNS (Collins et al., 2013; WHO, 2001). MNS disorders also contribute indirectly to mortality, due to suicide and other conditions (Collins et al., 2013). The prevalence of MNS disorders, such as anxiety and mood disorders, varies considerably across nations, due to cultural, biological and sociological factors (Chiao & Blizinsky, 2010; Kessler & Ustun, 2008). Cultural differences in neurobiological mechanisms of emotion may alter risk and resilience to psychopathology (Chiao & Blizinsky, in press; Hechtman, Raila, Chiao, Gruber, 2013). Within the US alone, approximately $6 trillion in costs are associated with mental illness in the next 15 years; yet the government spends only $2 per person per year on mental health care. The disparity in mental health care is especially prominent between high-and middle-to-low income countries where only a fraction of the population receives appropriate mental health care treatment (Collins et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2007).

Does culture affect the effectiveness of mental health care? One of the primary challenges in closing the gap in global mental health disparities is providing treatments that are equally effective across cultural and ethnic groups. Culture not only affects who seeks it (Cheon & Chiao, 2010; Yang et al., 2007), but also preference and response to a given medical treatment for mental health (Wang et al., 2007). Efficacy of psychopharmocology is known to vary across cultural and ethnic contexts (Bhugra & Bhui, 1999). Similar to Western sampling biases in behavioral and brain science research (Henrich, Heine & Norenzayan, 2000), the development, discovery and clinical testing of most psychiatric medicine has occurred in the West, although the use of drugs for clinical treatment has been worldwide (Bhugra & Bhui, 1999). Therapeutic effects of psychotropic drugs, ranging from antidepressants to neuroleptics, are known to vary across ethnic and cultural groups due to a number of social, environmental and biological factors (Bhugra & Bhui, 1999), including diet, stress levels and physiology. Depending on culture and ethnicity of the patient, differential dosages of antidepressants may produce similar levels of therapeutic effects for mood disorders, while similar dosages of antidepressants may produce different degrees of side effects (Escobar & Tuacon, 1980; Dimsdale, Ziegler, Graham, 1988). Cultural differences in efficacy of pharmacological treatments in mental health care highlight the fundamental need for a scientific understanding of the cultural and ethnic differences in neurobiological bases of emotion.

Emotion research in cultural neuroscience stands poised to provide major contributions to closing the gap in mental health disparities by identifying the key mechanisms by which etiology for psychopathology differs across cultures. Empirical advances in this research area can also guide the discovery and implementation of culturally-competent therapeutic and pharmocological treatments. Ultimately, when studying the cultural and biological bases of emotion in diverse multicultural populations, we gain leverage towards achieving the goal of equitable mental health care for all.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH 1R21MH098789-01, NIH 1R13CA162843 and 1R21NS074017-01A1to J.Y.C.

References

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature. 1994;372(6507):669–672. doi: 10.1038/372669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Gosselin F, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Schyns P, Damasio AR. A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature. 2005;433(7021):68–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambady N, Bharucha J. Culture and the brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:342–334. [Google Scholar]

- Avenanti A, Sirigu A, Aglioti SM. Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain. Current Biology. 2010;20:1018–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH. Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) and serotonin transporter (5-HTT) genes associated with observed parenting. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2008;3:128–134. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beja-Pereira A, Luikart G, England PR, Bradley DG, Jann OC, Bertorelle G, Chamberlain AT, Nunes TP, Metodiev S, Ferrand N, Erhardt G. Gene-culture coevolution between cattle milk protein genes and human lactase genes. Nature Genetics. 2003;35:311–313. doi: 10.1038/ng1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D, Bhui K. Ethnic and cultural factors in psychopharmacology. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 1999;5:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA, Lee TL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion. 2007;7:30–48. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon BK, Chiao JY. Cultural variations in implicit mental illness stigma. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2012;43:1058. doi: 10.1177/0022022112455457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon BK, Im DM, Harada T, Kim JS, Mathur VA, Scimeca JM, Parrish TB, Park HW, Chiao JY. Cultural modulation of the neural correlates of empathy: The role of other-focusedness. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51(7):1177–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon BK, Im D, Harada T, Kim J, Mathur VA, Scimeca JM, Parrish TB, Park H, Chiao JY. Cultural influences on neural basis of intergroup empathy. Neuroimage. 2011;57(2):642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon BK, Mrazek AJ, Pornpattananangkul N, Blizinsky KD, Chiao JY. Constraints, catalysts and coevolution in cultural neuroscience: Reply to commentaries. Psychological Inquiry. 2013;24(1):71–79. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2013.773599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Ambady N. Cultural neuroscience: Parsing universality and diversity across levels of analysis. In: Kitayama S, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of Cultural Psychology. NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Blizinsky KD. Culture-gene coevolution of individualism-collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277(1681):529–537. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Blizinsky KD. Population disparities in mental health: Insights from cultural neuroscience. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301440. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Cheon BK, Pornpattananangkul N, Mrazek AJ, Blizinsky KD. Cultural neuroscience: Progress and promise. Psychological Inquiry. 2013;24(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2013.752715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Harada T, Komeda H, Li Z, Mano Y, Saito DN, Parrish TB, Sadato N, Iidaka T. Neural basis of individualistic and collectivistic views of self. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(9):2813–2820. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Harada T, Komeda H, Li Z, Mano Y, Saito DN, Parrish TB, Sadato N, Iidaka T. Dynamic cultural influences on neural representations of the self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;22(1):1–11. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Hariri AR, Harada T, Mano Y, Sadato N, Parrish TB, Iidaka T. Theory and methods in cultural neuroscience. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5(2–3):356–361. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Immordino-Yang MH. Modularity and the cultural mind: Contributions of cultural neuroscience to cognitive theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(1):56–61. doi: 10.1177/1745691612469032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Mathur VA. Intergroup empathy: How does race affect empathic neural responses? Current Biology. 2010;20(11):R478–R480. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Hariri AR, Harada T, Mano Y, Hechtman LA, Sadato N, Parrish TB, Iidaka T. Cultural values predict amygdala response to emotion. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Chudek M, Henrich J. Culture-gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(5):218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Insel TR, Chockalingam A, Daar A, Maddox YT. Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health: Integration in Research, Policy, and Practice. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, González G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:339–355. [Google Scholar]

- de Greck M, Shi Z, Wang G, Zuo X, Yang X, Wang X, Northoff G, Han S. Culture modulates brain activity during empathy with anger. NeuroImage. 2012;59:2871–2882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl B, Habel U, Robinson S, Windischberger C, Kryspin-Exner I, Gur RC, Moser E. Amygdala activation during recognition of emotions in a foreign ethnic group is associated with duration of stay. Social Neuroscience. 2012;4(4):294–307. doi: 10.1080/17470910802571633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, Ivankovich O. Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: a comparison of African American, Hispanic, and White Patients. Pain Medicine. 2001;6:88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:203–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, Tuason VB. Antidepressant agents--a cross-cultural study. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1980;16(3):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin N. Ethnopharmacology, biobehavioral approaches in the anthropological study of indigenous medicines. Annual Review Anthropology. 1988;17:23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fincher CL, Thornhill R, Murray DR, Schaller M. Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2008;275:1279–1285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Family obligation and the academic motivation of adolescents from Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. In: Fuligni A, editor. Family obligation and assistance during adolescence: Contextual variations and developmental implications (New directions in child and adolescent development monograph) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc.; 2001. pp. 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand MJ, Raver JL, Nishii L, Leslie LM, Lun J, Lim BC, et al. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science. 2011;332(6033):1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch DE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Medicine. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Barrett LF. Emotion generation and emotion regulation: One or two depends on your point of view. Emotion Review. 2011;3:8–16. doi: 10.1177/1754073910380974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Lewis-Fernandez R, Martinez Pincay I, Shrout P, Guo J, Torres M, Canino G, Alegria M. Ataque de nervios as a marker of social and psychiatric vulnerability: results from the NLAAS. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56(3):298–309. doi: 10.1177/0020764008101636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Rogler LH. Research on culture-bound syndromes: New directions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1322–1327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Northoff G. Culture-sensitive neural substrates of human cognition: a transcultural neuroimaging approach. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9(8):646–654. doi: 10.1038/nrn2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana BS, Fera F, Goldman D, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechtman LA, Hariri AR, Harada T, Mano Y, Sadato N, Parrish TB, Iidaka T, Chiao JY. Dynamic cultural values predict amygdala response to emotion. Manuscript in preparation. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Hechtman LA, Raila H, Chiao JY, Gruber J. Positive emotion regulation and psychopathology: A cultural neuroscience perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. doi: 10.5127/jep.030412. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine S, Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2010;33(2–3):61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Immordino-Yang MH, McColl A, Damasio H, Damasio A. Neural correlates of admiration and compassion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(19):8021–8026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810363106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Sasaki JY. Emotion regulation: The interplay of culture and genes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6:865–877. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Sung YS, McClure SM. The neural basis of cultural differences in delay discounting. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:650–656. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Sherman DK, Mojaverian T, Sasaki JY, Park J, Suh EM, Taylor SE. Gene-culture interaction: Oxytocin receptor polymorphism (OXTR) and emotion regulation. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2:665–672. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Uskul AK. Culture, mind, and the brain: Current evidence and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:419–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DP. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:171–192. doi: 10.1086/432519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Aaker JL, Gardner WL. The pleasures and pains of distinct self-construals: The role of interdependence in regulatory focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:1122–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B-T, Paik J-W, Kang R-H, Chung S-Y, Kwon H-I, Khang H-S, Lyoo I-K, Chae J-H, Kwon J-H, Kim J-W, Lee M-S, Ham B-J. The neural substrates of affective face recognition in patients with Hwa-Byung and health individuals in Korea. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2009;10(4):560–566. doi: 10.1080/15622970802087130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR, Salman E, Jusino CM, Garfinkel R, Street L, Cardenas DL, Silvestre J, Fyer A, Carrasco JL, Davies S, Guarnaccia PJ, Klein DF. Ataques de nervios and panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:871–875. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist KA, Wager TD, Kober H, Bliss-Moreau E, Barrett LF. The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2012;35:121–143. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11000446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Johnstone T, Davidson RJ. Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(3):e1897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. Nonverbal "accents": Cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. Psychological Science. 2003;14:373–376. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.24461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Ellsworth PC, Mesquita B, Leu J, Tanida S, van de Veerdonk E. Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:365–381. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur VA, Harada T, Lipke T, Chiao JY. Neural basis of extraordinary empathy and altruistic motivation. Neuroimage. 2010;51(4):1468–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur VA, Harada T, Chiao JY. Racial identification modulates default network activity for same- and other-race faces. Human Brain Mapping. 2012;33(8):1883–1893. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, Fontaine J, Anguas-Wong AM, Arriola M, Ataca B, Bond MH, Boratav HB, Breugelmans SM, Cabecinhas R, Chae J, Chin WH, Comunian AL, DeGere DN, Djunaidi A, Fok HK, Friedlmeier W, Ghosh A, Glamcevski M, Granskaya JV, Groenvynck H, Harb C, Haron F, Joshi R, Kakai H, Kashima E, Khan W, Kurman J, Kwantes CT, Mahmud SH, Mandaric M, Nizharadze G, Odusanya JOT, Ostrosky-Solis F, Palaniappan AK, Papastylianou D, Safdar S, Setiono K, Shigemasu E, Singelis TM, Polackova Solcova Iva, Spieß E, Sterkowicz S, Sunar D, Szarota P, Vishnivetz B, Vohra N, Ward C, Wong S, Wu R, Zebian S, Zengeya A. Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relationship between emotional display rules and Individualism v. Collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2008;39:55–74. [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD. Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science. 2004;306:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1100907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita B, Frijda NH. Cultural variations in emotions: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:179–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzich J, Kleinman A, Fabrega H, Parron DL. Culture and Psychiatric Diagnosis. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Min SK. A study on the concept of hwa-byung. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association. 1989;28:604–615. [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Mineka S. Fear, phobias and preparedness: Toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychological Review. 2001;108:483–522. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek AJ, Chiao JY, Blizinsky KD, Lun J, Gelfand MJ. Culture-gene coevolution of tightness-looseness and the serotonin transporter gene. Culture and Brain. Accepted pending minor revisions, Culture and Brain. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s40167-013-0009-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafò MR, Brown SM, Hariri AR. Serotonin transporter (5HTTLPR) genotype and amygdala activation: a meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:852–857. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata A, Moser JS, Kitayama S. Culture shapes electrocortical responses during emotion suppression. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss036. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, Norenzayan A. Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review. 2001;108(2):291–310. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Gutchess AH. The cognitive neuroscience of aging and culture. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(3):105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Adolphs R. Emotion processing and the amygdala: from a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11(11):773–783. doi: 10.1038/nrn2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A New Scale for Use with Diverse Groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL, 3rd, Williams AK, Fillingim RB. A quantitative review of ethnic group differences in experimental pain response: do biology, psychology, and culture matter? Pain Medicine. 2012;13(4):522–540. 1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues SM, Saslow LR, Garcia N, John OP, Keltner D. Oxytocin receptor genetic variation relates to empathy and stress reactivity in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:21437–21441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909579106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saphire-Bernstein S, Way BM, Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is related to psychological resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:15118–15122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113137108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Masten CL, Berkman ET, Lieberman MD, Fuligni AJ. Gaining while giving: An fMRI study of the rewards of family assistance among White and Latino youth. Social Neuroscience. 2010;5:508–518. doi: 10.1080/17470911003687913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Gálvan A. Meaningful family relationships: Neurocognitive buffers of adolescent risk taking. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;25:374–387. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW. Cultural influences on emotional responding: Chinese American and European American dating couples during interpersonal conflict. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1997;28:600–625. [Google Scholar]

- Vogeley K, Roepstorff A. Contextualising culture and social cognition. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2009;13:511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Fox AS, Shackman AJ, Stodola DE, Caldwell JZK, Olson MC, Rogers GM, Davidson RJ. Compassion training alters altruism and neural responses to suffering. Psychological Science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0956797612469537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ. The uncertainty of it all. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11(12):499–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Zuo X, Wang X, Han S. Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:8525–8529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2418-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]