Abstract

Background and objectives

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that dialysis centers inform new patients of their transplant options and document compliance using the CMS-2728 Medical Evidence Form (Form-2728). This study compared reports of transplant education for new dialysis patients reported to CMS with descriptions from transplant educators (predominantly dialysis nurses and social workers) of their centers’ quantity of and specific educational practices. The goal was to determine what specific transplant education occurred and whether provision of transplant education was associated with center-level variation in transplant wait-listing rates.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Form-2728 data were drawn for 1558 incident dialysis patients at 170 centers in the Heartland Kidney Network (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska) in 2009–2011; educators at these centers completed a survey describing their transplant educational practices. Educators’ own survey responses were compared with Form-2728 reports for patients at each corresponding center. The association of quantity of transplant education practices used with wait-listing rates across dialysis centers was examined using multivariable negative binomial regression.

Results

According to Form-2728, 77% of patients (n=1203) were informed of their transplant options within 45 days. Educators, who reported low levels of transplant knowledge themselves (six of 12 questions answered correctly), most commonly reported giving oral recommendations to begin transplant evaluation (988 informed patients educated, 81% of centers) and referrals to external transplant education programs (959 informed patients educated, 81% of centers). Only 18% reported having detailed discussions about transplant with their patients. Compared with others, centers that used more than three educational activities (incident rate ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.73) had higher transplant wait-listing rates.

Conclusions

While most educators inform new patients that transplant is an option, dialysis centers with higher wait-listing rates use multiple transplant education strategies.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, dialysis, ethnicity, Transplant education practices, Wait-listing

Introduction

Seventy percent of patients in the United States with ESRD (>430,000 patients in approximately 6000 dialysis centers) receive some form of dialysis to sustain life (1). Because only 37% of dialysis patients are living after 5 years (1), comprehensive education about the options of deceased-donor kidney transplant (DDKT) and living-donor kidney transplant (LDKT) should occur as quickly as possible, ideally before a patient’s native kidney fails (2) or immediately following the start of dialysis.

To support the provision of transplant education, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' (CMS's) Conditions for Coverage for ESRD Facilities introduced a requirement in 2005 that dialysis centers inform patients of their option for transplant and report progress of this within 45 days of dialysis initiation using Form CMS-2728; this was reinforced in CMS’s 2008 Conditions for Coverage for ESRD Facilities (3). When education is successful, pursuit of transplant by dialysis patients increases. Dialysis patients who report having received information about transplantation have higher transplant wait-listing rates (4,5).

Unfortunately, substantial barriers affect whether all patients receive transplant education in dialysis centers (6), with black patients, older patients, obese patients, uninsured patients, and Medicaid-insured patients less likely to receive education about transplant before presenting at a transplant center (7,8). Transplant educators in dialysis centers (predominantly nurses and dialysis social workers) themselves report having limited time and knowledge to successfully educate patients about transplantation (9), with educators at for-profit dialysis centers less likely to administer high-quality, more intensive transplant educational strategies (e.g., one-on-one discussions) compared with nonprofit centers (6). Ultimately, dialysis centers with higher proportions of black and diabetic patients, more patients with lower incomes or less comprehensive insurance, and more patients undergoing hemodialysis versus other forms of dialysis, as well as centers in neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic status and with fewer transplant centers nearby, have lower wait-listing and transplant rates (10–13). However, because CMS does not capture information about the specific delivery of transplant education within a center, less is known about the variation in educational practices across centers or the effect of specific education practices within these dialysis centers on wait-listing rates. Because of these limitations, studies of transplant education within dialysis centers based on reporting of compliance with the CMS requirement alone cannot assess what types of educational practices might have occurred among informed patients.

To advance the understanding of the content of transplant education being delivered at dialysis centers, methods of delivery, and effect on transplant pursuit, this research team surveyed educators from 185 dialysis centers in 2009–2011 about their specific transplant educational practices and linked these survey data with CMS Form-2728 records for patients who initiated dialysis at these centers 6 months before each educator’s survey. The aims of the study were to (1) compare indications of transplant education on the Form-2728 against specific educational practices described by educators, (2) determine associations between dialysis center characteristics and use of transplant educational practices by educators, and (3) determine educational factors and center characteristics associated with variation in transplant wait-listing across dialysis centers.

Materials and Methods

Participants: Dialysis Centers and Educators

From 2009 to 2011, as part of a transplant quality improvement initiative, we examined the transplant education practices occurring within dialysis centers in the Heartland Kidney Network (ESRD Network 12). The Heartland Kidney Network, a CMS contractor, oversaw 274 dialysis centers, providing care for >14,000 dialysis patients in Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas (14). All dialysis centers in the Heartland Kidney Network were invited to attend one of 11 all-day transplant education trainings in Missouri (six trainings), Iowa (two trainings), Nebraska (two trainings), or Kansas (one training). Only adult, outpatient dialysis centers were eligible for participation in the study, and centers were encouraged to send multiple dialysis staff who were in the position to offer transplant education to their patients as representatives.

Immediately before and after these training sessions, all educators in attendance were invited to participate in a study assessing their transplant educational practices, with interested educators signing a written consent form. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Washington University School of Medicine (project # 09–0451) and the Saint Louis University institutional review board (project # 21502).

Data Sources and Measurement

Data for this study were drawn from several sources, including educators’ self-reported surveys administered at the trainings, CMS Form-2728 records for patients who initiated dialysis at corresponding centers within 6 months before each educator’s initial survey date and transplant wait-listing events for the previous 1.5 years as captured in the US Renal Data System (USRDS) (1), dialysis center characteristics from the Dialysis Facility Reports (DFR) (15), and ZIP code–level socioeconomic data from the US Census (16). Dialysis patient records from the USRDS were aggregated by center, linked to educator survey data, and linked to center characteristics available from the DFR and the Census data using an anonymous, randomly generated, deidentified linkage key for each dialysis center with the linkages facilitated through a USRDS contractor. Analytic data were anonymous, with all center names removed. No patient identifiers were accessible to study investigators.

The transplant education survey measured educators’ demographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity, sex, age, job title, and the number of years working in dialysis centers, and the use of any of 12 transplant education practices (yes/no) listed in Table 1 (e.g., recommending that patients be evaluated for transplant, referring patients to an educational program at a transplant center, having a detailed discussion about the risks and benefits of DDKT or LDKT). It also assessed educators’ own level of transplant knowledge on a 12-question scale (e.g., “What percent of transplanted kidneys function for at least 1 year?”). Finally, the survey asked whether (1) transplant education was provided on a yearly basis to all transplant-eligible patients (yes/no) and (2) there was a formal transplant education program in the center (yes/no).

Table 1.

Transplant educators’ practices and number of patients served

| Practice | Educators Using Strategy, %a (n) | Informed Patients With Access to Strategy, % (n)b |

|---|---|---|

| Recommend being evaluated for transplant | 81 (138) | 82 (988) |

| Refer patients to educational program at a transplant center/kidney organization | 81 (138) | 80 (959) |

| Recommend learning more about transplant | 72 (123) | 74 (890) |

| Distribute transplant center phone numbers | 68 (115) | 73 (878) |

| Provide handouts/brochures about transplant | 63 (107) | 64 (768) |

| Offer an opportunity to talk to a kidney recipient | 29 (50) | 32 (379) |

| Have a detailed discussion about the advantages/risks of deceased donor transplant | 18 (31) | 25 (297) |

| Have a detailed discussion about the advantages/risks of living donor transplant | 18 (31) | 22 (263) |

| Show transplant video(s) | 17 (29) | 19 (223) |

| Provide list of transplant websites | 17 (29) | 14 (173) |

| Provide education to share with prospective living donors | 16 (28) | 15 (179) |

| Display transplant posters in waiting room | 11 (19) | 10 (119) |

Percentage who reported using each educational strategy. Educator sample was n=170.

We first determined the number of patients who indicated that they had been informed of their transplant option on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Form-2728 within each dialysis center. We then determined the number of educators (centers) who reported using each strategy and summed the number of “informed”patients from these centers to obtain the total number of “informed” patients exposed to each strategy. Proportions are of sample of informed patients, n=1203.

Because multiple educators from 71 of the 185 participating dialysis centers attended the trainings, we chose a single educator with the greatest engagement in transplant education to represent each center as assessed by their reports of educating at least one patient about transplant, knowledge of how many patients were educated at their center in the 3 months before the training, how much time it took to educate a patient, whether they answered yes to the question, “Are you or will you be conducting transplant education directly?”, and whether they reported having a detailed discussion about risks and benefits of transplant or using the most educational practices.

CMS Form-2728 records submitted to CMS from centers where representatives attending the transplant education trainings were extracted for patients starting dialysis within the 6 months before the educator’s survey date. For each patient, we extracted responses reported for CMS Form-2728 questions 26 (“Has the patient been informed of kidney transplant options?”: yes/no) and 27 (“If NOT informed of transplant options, please check all that apply: Medically unfit; Patient has not been assessed; Patient declines information; Psychologically unfit; Unsuitable due to age; Other.” To quantify exposure to educational practices, each new patient was considered to have potentially been exposed to all of their educators’ reported transplant education practices.

We also accessed USRDS transplant wait-listing records for dialysis centers that sent a representative to the trainings and calculated the annualized wait-listing rates for each center during the 1.5 years before the date of the transplant education training (censored at date of training or death). Using data from the DFR, we determined, for each dialysis center, the percentage of patients who were black, female, and age 65 years or older (categorized as >50% or ≤50%). Also from these data, we determined whether centers were for-profit or nonprofit in their ownership and the total number of patients served. Data from the Rural Health Research Center were accessed to determine whether dialysis centers were located in rural (<50,000 population) or urban (≥50,000 population) areas (17). We used 2000 US Census data to calculate a residential ZIP code–level index of socioeconomic status (SES) as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (18), which ranges from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicate higher SES) and incorporates indicators including median household income, poverty, property values, education levels, and household crowding. For analyses, we calculated the median SES score for patients at each center and then dichotomized centers at above the median versus equal to or below the median index score (19). Finally, we determined the distance (in miles) between the dialysis centers and the nearest transplant center using ArcGIS 10.0 Network distance tools, accounting for road network in that area.

Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed using SAS software, version 9.4, and all statistical tests used a two-sided α value of 0.05. Patient, educator, and dialysis center characteristics and transplant education practices were described using means, medians, and proportions. Characteristics of centers that attended and did not attend trainings were compared using chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests. To compare indications of transplant education for new patients reported to CMS on Form-2728 with their educators’ descriptions of detailed educational practices, we totaled the number and proportion of educators that used each transplant education strategy and then, for each dialysis center, linked the number of patients informed on Form-2728 about their transplant options in the prior 6 months with the specific educational strategies used by their specific educator. The relationships between 12 educational practices and eight dialysis facility characteristics were tested using chi-square tests, with a P value corrected to account for multiple comparisons (0.05/8=0.006).

Univariate and multivariable negative binomial models were used with the log of person-years as the offset to calculate incident rate ratios (IRRs) of wait-listing for transplant. To model the association between dialysis center educational practices and wait-listing rates, we first examined the univariate associations of all 12 educational practices, whether centers reported educating their patients yearly, and whether they had a formal transplant education program individually. Second, we summed the number of practices a educator reported using and grouped these values into tertiles (three or fewer educational practices, four or five educational practices, and six or more educational practices). Along with the educational variables, other univariate associations of variables hypothesized to affect dialysis centers’ wait-listing rates were tested, including educators’ transplant knowledge (dichotomized at the median), number of years of experience in dialysis (dichotomized at the median), the ownership status of the dialysis center, whether the center was rural or urban, the distance of the dialysis center from the nearest transplant center (dichotomized at the median), the total patients served by the dialysis center (dichotomized at the median), whether the center served >50% black patients, >50% female patients, >50% patients age 65 years or older, and the SES score (dichotomized at the median) of the center. Finally, we entered all univariate-significant variables into a multivariable negative binomial model, then used backward selection to predict wait-listing rates at the dialysis center level.

Results

Participating Dialysis Centers and Educators

Of the 274 dialysis centers in the Heartland Kidney Network, representatives from 203 dialysis centers attended. Of those in attendance, eight were ineligible for the study because they were acute or pediatric centers and 10 did not consent to participate, leaving 185 adult, outpatient dialysis centers (68% response rate). CMS Form-2728 records in the USRDS database could not be linked for six dialysis centers, five dialysis centers did not initiate any dialysis patients in the 6 months before attending a training, and four centers were missing education practice variables from the educator survey, leaving a sample of 170 centers for analysis of the study aims. When we compared the 185 centers from the Heartland Kidney Network that attended a training and were eligible and consented to participate in the study to the 71 centers that did not attend the training, we found no significant differences in whether the centers were for-profit or nonprofit; were in rural versus urban locations; or had >50% or 50% black patients, female patients, or patients 65 years of age or older (data not shown). However, the median size of centers that attended the trainings was higher than that of centers that did not attend (43 patients versus 35 patients; P=0.02).

Most participating dialysis centers had ≤50% female (76%) and black (85%) patients, were from for-profit organizations (75%), and were located in rural settings (60%). While most reported providing yearly transplant education to all transplant-eligible patients (81%), the majority did not report having a formal transplant education program in operation (79%) (Table 2). Most educators attending the training were female (97%), white (91%), and either social workers (51%) or nurses (23%). On average, these educators had 11 years of experience working with dialysis patients. At the start of the training, the average number of transplant knowledge questions educators could correctly answer was six of 12 (50% correct).

Table 2.

Characteristics of transplant educators and dialysis centers

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Transplant educator (n=170) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 165 (97) |

| Male | 5 (3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 155 (91) |

| Black | 12 (7) |

| Hispanic or Latino (considered mutually exclusive from white and black) | 3 (2) |

| Job title | |

| Social worker | 86 (51) |

| Nurse | 39 (23) |

| Nurse manager/facility administrator | 38 (22) |

| Dialysis technician | 5 (3) |

| Other | 2 (1) |

| Age (yr) | 46±10 |

| Time working with dialysis patients (yr) | 11±8 |

| Dialysis center characteristics (n=170) | |

| Rural or urban location | |

| Rural | 102 (60) |

| Urban | 67 (39) |

| Dialysis center ownership status | |

| For-profit | 128 (75) |

| Nonprofit | 41 (24) |

| >50% female patients (yes) | 41 (24) |

| >50% black patients (yes) | 26 (15) |

| >50% aged ≥65 yr (yes) | 80 (47) |

| Distance from dialysis center to nearest transplant center (miles) | 38 (12–90) |

| Size of dialysis center (total no. of patients served) | 43 (26–65) |

| AHRQ SES index scorea | 58 (54–61) |

| Transplant education practices at centers | |

| Yearly transplant education provided to all transplant-eligible patients (yes) | 137 (81) |

| Formal transplant education program in operation at center (yes) | 35 (21) |

Values are expressed as number (percentage), mean±SD, or median (range). AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; SES, socioeconomic status.

Data for 17 dialysis centers missing.

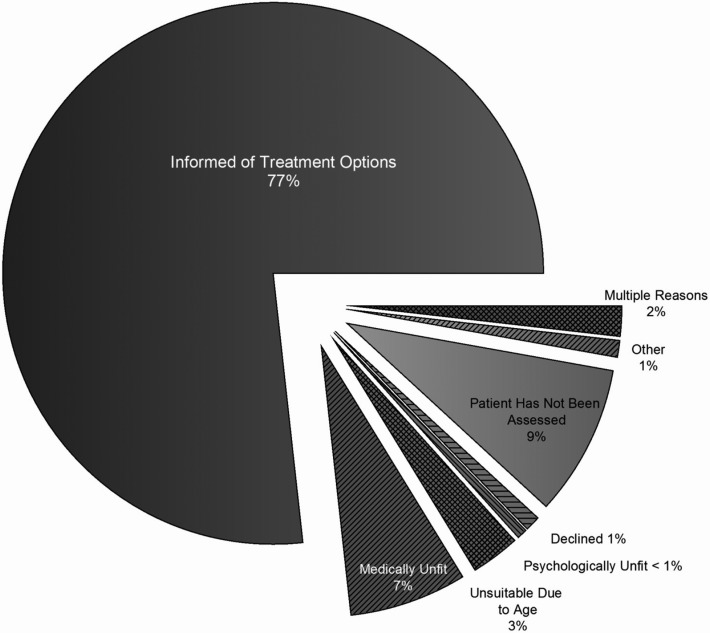

Comparison of CMS Form-2728 Patient Data and Educator Practices

In the 6 months before the training dates, CMS Form-2728 was submitted to CMS for 1558 incident dialysis patients from 170 centers. Of these, 77% (n=1203) of the forms indicated that the patient had been “informed of their kidney transplant options” within 45 days of starting dialysis (Figure 1). The 355 patients who were not informed of their treatment options according to CMS Form-2728 were reported to be medically unfit (7% of total), unsuitable because of age (3%), or psychologically unfit (<1%). In the remaining cases, the patient declined transplant information (1% of total) or was not informed for more than one reason (2% of total). Only 9% of patients, 144 patients total, were not assessed.

Figure 1.

Whether patient has been informed about transplant on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Form-2728.

The 1203 patients reported to be informed on CMS Form-2728 were likely affected by the common transplant education practices used by educators, including providing oral recommendations to be evaluated for transplant (988 informed patients, 81% of centers using this strategy), referrals to external transplant education programs (959 informed patients, 81% of centers), and recommendations to learn more about transplant (890 informed patients, 72% of centers) (Table 1). On the basis of educators’ reports, only 297 informed patients (18% of centers) had detailed discussions about the risks and benefits of DDKT, 263 informed patients (18% of centers) had detailed discussions about the risks and benefits of LDKT, 223 informed patients watched transplant video(s) (17% of centers), 173 informed patients received a list of transplant websites (17% of centers), and 179 informed patients (16% of centers) received educational resources to share with prospective living donors.

Variation in Transplant Educational Practices by Dialysis Center

We first examined the association of 12 educational practices and eight dialysis facility characteristics. Only associations significant at P<0.01 are reported because of multiple comparisons. Compared with centers with more than half their patients ≥65 years or older, those with younger patients were more likely to orally recommend that patients be evaluated for transplant (90% versus 71%; P=0.002). Compared with for-profit centers, nonprofit centers were more likely to provide education to share with prospective living donors (32% versus 12%; P=0.003). Finally, the following center characteristics were associated with greater likelihood of distributing transplant center phone numbers: urban versus rural centers (78% versus 51%; P<0.001), centers within shorter distances (below the median) from the nearest transplant center compared with longer distances (above median) (85% versus 49%; P<0.001), and centers with above median Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality SES index score compared with those with below median scores (84% versus 50%; P<0.001).

Variables Associated with Wait-listing among Dialysis Centers

After the univariately significant variables were entered into a multivariable negative binomial model, compared with dialysis centers whose educators used three or fewer educational practices, those that used four or five practices (IRR, 1.36; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.07 to 1.73) had significantly higher rates of transplant wait-listing. Additionally, wait-listing rates were higher among nonprofit dialysis centers (IRR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.37), dialysis centers closer to the nearest transplant center (IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.32), and dialysis centers with ≤50% black patients (IRR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.28 to 1.75) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with wait-listing among dialysis centers (n=170)

| Variable | Univariate IRR (95% CI) | Multivariable IRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of education practices | ||

| Low (≤3 practices) | Reference | Reference |

| Medium (4 or 5 practices) | 1.27 (0.97 to 1.67) | 1.36 (1.07 to 1.73)f |

| High (≥6 practices) | 1.17 (0.86 to 1.59) | 1.19 (0.91 to 1.55) |

| Number of years educator worked with dialysis patients | — | |

| >Mediana | 1.20 (0.95 to 1.51) | |

| ≤Median | Reference | |

| Educator’s transplant knowledge | — | |

| >Medianb | 1.29 (0.75 to 1.20) | |

| ≤Median | Reference | |

| Ownership status | ||

| Nonprofit | 1.20 (1.36 to 1.44) | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37)f |

| For-profit | Reference | Reference |

| Percentage black among total patients | ||

| >50% | Reference | Reference |

| ≤50% | 1.32 (1.12 to 1.56) | 1.50 (1.28 to 1.75)f |

| Percentage female among total patients | ||

| >50% | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.26) | — |

| ≤50% | Reference | |

| Percentage age ≥65 yr among total patients | — | |

| >50% | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.07) | |

| ≤50% | Reference | |

| Rural versus urban location | ||

| Rural | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.07) | — |

| Urban | Reference | |

| Distance from nearest transplant center | ||

| > Medianc | Reference | Reference |

| ≤ Median | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.24) | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.32)f |

| Total patients served | ||

| >Mediand | 1.12 (0.87 to 1.44) | — |

| ≤Median | Reference | |

| AHRQ SES index | — | |

| >Median scoree | 1.24 (0.97 to 1.57) | |

| ≤Median score | Reference |

Negative binomial regression was used to determine the association between dialysis center characteristics and wait-listing rates. Variables that were univariately significant at P<0.15 were entered into a multivariable model, then variables that were multivariable significant at P<0.05 were retained for the final model. Incident rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using negative binomial regression. Dashes denote variables removed from the multivariable model in the backward selection procedure. AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; SES, socioeconomic status; IRR, incident rate ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Median years of experience working with dialysis patients was 11.

Median transplant knowledge score was 6.

Median distance from dialysis centers to the nearest transplant center was 38 miles.

Median number of patients per center was 43 patients.

Median SES index score was 58 (out of 100).

p<0.05

Discussion

A recent consensus conference (20) identifying best practices for increasing LDKT rates formally recommended that outreach and education by community nephrologists, dialysis centers, and nonprofit organizations occur and be repeated regularly to ensure that all patients know about their DDKT and LDKT options. Research confirms that kidney patients who begin transplant evaluation having received more comprehensive education from community nephrologists or within dialysis centers are more likely to complete transplant evaluation successfully (5), get on the transplant waiting list (21), and receive LDKTs (7,22). In this study, reports to CMS using CMS Form-2728 and self-reports by educators about transplant education practices generally occurring in each dialysis center indicate that at least 77% of new dialysis patients were receiving some kind of education about transplant. However, when we examined what kind of educational practices were commonly occurring for these informed dialysis patients in 170 centers in the Midwest, we found high levels of variation and quality. At least 80% reported that they most commonly provided verbal recommendations to be evaluated for transplant and referrals to an outside transplant education program. Centers where educators reported doing minimal educational practices, three practices or fewer in total, had lower transplant wait-listing rates than centers where educators provided more resources and educational practices.

In light of our findings that educators themselves have poor knowledge of transplantation and have not established formal educational programs within their centers, the low frequencies of providing comprehensive educational practices is understandable. A recent study by Salter et al. found that educators reported educating their patients about transplant more often than their patients reported being educated themselves, which may indicate a difference in educators’ and patients’ definitions and perceptions of true transplant education (4). Although precise definitions of informed consent vary (23), a universal component, as established by the Belmont Report, includes an explanation of the risks and benefits of one’s medical treatment options (24). In this study, only 18% of educators reported having detailed discussions about the risks and benefits transplant with their patients. Further clarification of the policies about what dialysis centers must do to ensure compliance with CMS requirements regarding transplant education would help translate compliance to delivery of meaningful education. A clear definition of comprehensive and satisfactory patient education about the benefits and risks of this treatment option within dialysis centers is needed (20).

In addition, an interesting trend emerged where educators may be making decisions about what level of education about transplant to provide based on an assessment of its value for improving the health or quality of life of their general patient caseload. Specifically, this study found that educators working in centers with patients who were older, of lower SES, farther away from transplant centers, and in rural settings were less likely to recommend transplant as an option or distribute transplant center phone numbers. This finding may help explain the documented lower access to transplantation among rural kidney patients (25). Concerns that dialysis patients who are of low SES might be unable to pay for the costs of immunosuppressant drugs in the future may be preventing some educators from educating patients about this treatment option (26). Future research must continue to examine whether these trends persist in a national sample of dialysis centers. However, one promising strategy for improving transplant education in centers with low-SES patients and those in rural areas farther away from transplant centers may be to provide educators with training about transplant’s value for their patients; access to more patient-centered educational resources about transplantation; and resources, such as free transportation to a transplant center or more reimbursement for evaluation-related expenses to overcome patients’ financial burdens related to transplant (9,27,28).

Consistent with prior studies (10,29–31), we also found that patients in centers with greater proportions of black patients had significantly lower transplant wait-listing rates. It is known that patients identifying as racial minorities are less likely to receive transplant education (7,32); however, we found a significant race effect on wait-listing rates even when controlling for the number of educational practices occurring within the center. Black dialysis patients may experience more challenges related to SES (30,33), medical mistrust (34,35), and health literacy (36) that reduce their likelihood of becoming motivated to pursue transplant; this, in turn may explain why centers with high proportions of black patients have lower wait-listing rates. With this trend also apparent for Hispanic patients (37), our results suggest that future educational interventions to reduce the racial disparity in access to transplant should focus on dialysis centers with high proportions of patients who are ethnic/racial minorities. Further, transplant educational approaches may need to be culturally or individually tailored to better serve patients of different racial/ethnic groups who have different knowledge gaps, fears about DDKT or LDKT, or biases about transplant (38–40).

This study indicates that more transplant education can result in higher wait-listing rates. Educators who reported using four or five educational practices had significantly higher wait-listing rates than educators who used fewer practices. Previous studies have indicated that some educators may not have enough time in their schedules to educate patients about transplant (9). Multiple transplant education interventions help increase the transplant knowledge, informed transplant decision-making, and pursuit or receipt of DDKT or LDKTs among patients with ESRD (28,41–44). However, future research should continue to compare the effectiveness of different educational strategies to determine how much education is necessary, which educational strategies matter the most, and how to cost-effectively disseminate transplant education into the 6000 dialysis centers.

This study had many limitations. First, while educators in this study reported the educational practices that were specifically occurring within their centers, other educators could be providing education as well; moreover, not every patient reported to have been informed on CMS Form-2728 definitely received each of the educational strategies the educator reported using. Second, because few of the participants in this study were dialysis nephrologists, it is not clear whether low participation among these providers reflects their inability to attend the transplant education trainings where survey data were collected or whether it reflects a trend of less frequent participation in transplant education among dialysis nephrologists compared with their dialysis staff. Third, in the analysis of wait-listing rates preceding the educator trainings, the educational practices currently occurring within each center might not have been delivered as far back as 1.5 years. Future studies will need to replicate this study prospectively. Nonetheless, with the present dearth of evidence around the effectiveness of specific transplant education practices in dialysis centers, these findings contribute critical new knowledge about the specificity and variation of actual transplant education practices used in dialysis centers. Fourth, although we used several rich sources of data, not all variables potentially associated with our outcomes, such as the communication style and effectiveness of the educator, could be obtained. Finally, this study considered regional data within Midwest dialysis centers, and its results may not be generalizable to the national patterns of transplant education in dialysis centers. Future research must explore whether these patterns remain at a national level.

Multiple studies have shown that many dialysis patients have poor knowledge about transplants as a treatment option (7,45). This study provides preliminary evidence that variation in the quantity of educational practices occurring within dialysis centers is high and can affect the numbers of dialysis patients moving forward to be evaluated and listed for transplant. It also indicates that using more types of transplant educational practices with patients, instead of simply informing patients of their option for transplant, may assist with ultimate pursuit of transplant. Clear, national standards for transplant education occurring in dialysis centers in the United States may help ensure informed patient decision-making and increase wait-listing rates.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions and assistance of colleagues at Washington University School of Medicine who helped make this work possible. The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the United States government.

This research was funded by Health Resources and Services Administration grant R39-OT10582 and the University of California, Los Angeles, Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1-TR000124.

This work was presented in part at the American Transplant Congress in May 2013.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “The Other Half of Informed Consent: Transplant Education Practices in Dialysis Centers,” on pages 1507–1509.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : USRDS 2013 Annual Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Diseases, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Matas AJ, Ellison MD, Gill JS, Kausz AT: Preemptive kidney transplantation: the advantage and the advantaged. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1358–1364, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Conditions for Coverage for End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities; Final Rule In: Department of Health and Human Services (Ed.). Federal Register April 15, 2008. Available at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2008/04/15/08-1102/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-conditions-for-coverage-for-end-stage-renal-disease-facilities [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salter ML, Orandi B, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Meoni LA, Jaar BG, Sozio SM, Kao WH, Parekh RS, Segev DL: Patient- and provider-reported information about transplantation and subsequent waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2871–2877, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Johansen KL: Impact of race on predialysis discussions and kidney transplant preemptive wait-listing. Am J Nephrol 35: 305–311, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balhara KS, Kucirka LM, Jaar BG, Segev DL: Disparities in provision of transplant education by profit status of the dialysis center. Am J Transplant 12: 3104–3110, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J: Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 995–1002, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL: Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 12: 351–357, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman AD, Goalby C, Hyland SS, McCabe M,Dinkel KM: Transplant education practices and attitudes in dialysis centers: dialysis leadership weighs in. J Nephrol Ther 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280: 1148–1152, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patzer RE, Plantinga L, Krisher J, Pastan SO: Dialysis facility and network factors associated with low kidney transplantation rates among United States dialysis facilities. Am J Transplant 14: 1562–1572, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plantinga L, Pastan S, Kramer M, McClellan A, Krisher J, Patzer RE: Association of U.S. Dialysis facility neighborhood characteristics with facility-level kidney transplantation. Am J Nephrol 40: 164–173, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schold JD, Gregg JA, Harman JS, Hall AG, Patton PR, Meier-Kriesche HU: Barriers to evaluation and wait listing for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1760–1767, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heartland Kidney Network: 2011 Annual Report. Kansas City, MO, End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Network 12, Network Coordinating Council, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center and Arbor Research Collaborative for Health : Dialysis Facility Report, Ann Arbor, MI, Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Bureau of the Census: United States Census 2000, Washington, DC, United States Federal Government, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rural Health Research Center: Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCAs). 2012. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-data.php

- 18.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Creating and validating an index of socioeconomic status. In: Creation of New Race-Ethnicity Codes and SES Indicators for Medicare Beneficiaries, Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Creation of New Race-Ethnicity Codes and Socioeconomic Status (SES) Indicators for Medicare Beneficiaries. Final Report Ed. Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, Cohen DJ, Cooper M, Danovitch GM, Dew MA, Gordon EJ, Mandelbrot DA, McGuire S, Milton J, Moore DR, Morgievich M, Schold JD, Segev DL, Serur D, Steiner RW, Tan JC, Waterman AD, Zavala EY, Rodrigue JR: Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant 15: 914–922, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutner NG, Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Amaral S: Perspectives on the new kidney disease education benefit: early awareness, race and kidney transplant access in a USRDS study. Am J Transplant 12: 1017–1023, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cankaya E, Cetinkaya R, Keles M, Gulcan E, Uyanik A, Kisaoglu A, Ozogul B, Ozturk G, Aydinli B: Does a predialysis education program increase the number of pre-emptive renal transplantations? Transplant Proc 45: 887–889, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buccini LD, Caputi P, Iverson D, Jones C: Toward a construct definition of informed consent comprehension. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 4: 17–23, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services : The Belmont Report, Washington, D.C.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvili N, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR, Segev DL, Gentry SE, Tuttle-Newhall J, Lentine KL: The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2276–2288, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans RW, Applegate WH, Briscoe DM, Cohen DJ, Rorick CC, Murphy BT, Madsen JC: Cost-related immunosuppressive medication nonadherence among kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2323–2328, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neyhart CD: Education of patients pre and post-transplant: Improving outcomes by overcoming the barriers. Nephrol Nurs J 35: 409–410, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Pastan S, Amaral S, Gazmararian JA, Klein M, Kutner N, McClellan WM: Impact of a patient education program on disparities in kidney transplant evaluation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 648–655, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, David-Kasdan JA, Carlson D, Fuller J, Marsh D, Conti RM: Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med 343: 1537–1544, 2, 1537, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM: Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1333–1340, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Schrager JD, Pastan S, Amaral S, Gazmararian JA, Klein M, Kutner N, McClellan WM: The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the Southeastern United States. Am J Transplant 12: 358–368, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM: The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 341: 1661–1669, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waterman AD, Rodrigue JR, Purnell TS, Ladin K, Boulware LE: Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: Priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol 30: 90–98, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR: Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep 118: 358–365, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Jr, Shaker L: Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med 166: 896–901, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grubbs V, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Hsu CY: Health literacy and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 195–200, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, O’Hare AM, Chertow GM: Racial ethnic differences in rates and determinants of deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 743–751, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreuter MW, Sugg-Skinner C, Holt CL, Clark EM, Haire-Joshu D, Fu Q, Booker AC, Steger-May K, Bucholtz D: Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African-American women in urban public health centers. Prev Med 41: 53–62, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Redding CA: Tailored communications for smoking cessation: past successes and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev 25: 49–57, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waterman AD, Rodrigue JR: Transplant and organ donation education: what matters? Prog Transplant 19: 7–8, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkins F, Bozik K, Bennett K: The impact of patient education and psychosocial supports on return to normalcy 36 months post-kidney transplant. Clin Transplant 17[Suppl 9]: 78–80, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Melancon JK, Falcone B, Ephraim PL, Jaar BG, Gimenez L, Choi M, Senga M, Kolotos M, Lewis-Boyer L, Cook C, Light L, DePasquale N, Noletto T, Powe NR: Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 476–486, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urstad KH, Øyen O, Andersen MH, Moum T, Wahl AK: The effect of an educational intervention for renal recipients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Transplant 26: E246–E253, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waterman A, Hyland S, Goalby C, Robbins M, Dinkel K: Improving transplant education in the dialysis setting: The “Explore Transplant” initiative. Dial Transplant 39: 236–241, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, Barre P, Takano T, Soroka S, Mujais S, Rodd K, Mendelssohn D: Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int 74: 1178–1184, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]