Abstract

Background and objective

Tele monitoring (TM) of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has gained much interest, but studies have produced conflicting results. Our aim was to investigate the effect of TM with the option of video consultations on exacerbations and hospital admissions in patients with severe COPD.

Materials and methods

Patients with severe COPD at high risk of exacerbations were eligible for the study. Of 560 eligible patients identified, 279 (50%) declined to participate. The remaining patients were equally randomized to either TM (n=141) or usual care (n=140) for the 6-month study period. TM comprised recording of symptoms, saturation, spirometry, and weekly video consultations. Algorithms generated alerts if readings breached thresholds. Both groups received standard care. The primary outcome was number of hospital admissions for exacerbation of COPD during the study period.

Results

Most of the enrolled patients had severe COPD (forced expiratory volume in 1 second <50%pred in 86% and ≥hospital admission for COPD in the year prior to enrollment in 45%, respectively, of the patients). No difference in drop-out rate and mortality was found between the groups. With regard to the primary outcome, no significant difference was found in hospital admissions for COPD between the groups (P=0.74), and likewise, no difference was found in time to first admission or all-cause hospital admissions. Compared with the control group, TM group patients had more moderate exacerbations (ie, treated with antibiotics/corticosteroid, but not requiring hospital admission; P<0.001), whereas the control group had more visits to outpatient clinics (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Our study of patients with severe COPD showed that TM including video consultations as add-on to standard care did not reduce hospital admissions for exacerbated COPD, but TM may be an alternative to visits at respiratory outpatient clinics. Further studies are needed to establish the optimal role of TM in the management of severe COPD.

Keywords: COPD, tele health care, video consultations, exacerbations, admissions

Introduction

Exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of hospitalization and premature death. The rate of re-admission is approximately 50% within the first 12 months.1 To monitor, optimize treatment, and prevent exacerbation in COPD, the GOLD strategy document recommends regular follow-up for patients suffering from COPD.2 The Danish Health Authorities recommend that patients with severe and very severe COPD are followed up in the outpatient clinic twice yearly and seen for unscheduled visits as needed, whereas patients with mild-to-moderate COPD are expected to be managed, including regular follow-ups, by their general practitioner.3

Tele monitoring (TM) has gained enormous interest because it is seen not only as a way of providing prompt medical intervention in the early phase of deterioration in the patient’s condition and by that prevent hospital admissions but also as a way of reducing costs and time spent with transportation.4

In recent years, TM for patients with COPD has been evaluated in various designs and setups. A few studies have evaluated the effect of TM immediately after discharge from a hospital admission for COPD5,6 and some have combined TM with education, self-management, and/or rehabilitation,7–9 whereas only a few studies have included video conferences.6–8 In keeping with this, review articles have, not surprisingly, found it difficult to draw valid conclusions and have, therefore, recommended further research, also because the number of studies in this area is still very limited.10,11 The most positive results have, so far, been seen in studies comprising a large number of patients with COPD on long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT).12–14

A large British randomized study of 3,230 patients with diabetes, heart failure, or COPD revealed that TM was associated with a reduction in mortality, number of hospital admissions, and bed days by 4% in absolute terms.15 Unfortunately, the findings for each of the three disease groups are not provided in the published article.15

Recently, Pinnock et al published their findings from a large randomized study with patients with COPD recruited through general practice and reported that TM had no effect on hospital admissions or quality of life,8 and in keeping with this, Hamad et al16 failed to establish the value of TM in the early detection of COPD exacerbations. However, although previous studies indicate that TM may not be a cost-effective intervention,17,18 it has been reported that TM has a positive effect of health-related quality of life and anxiety.18 As TM involves substantial health-care costs and commitment, there is a need for well-designed longer-term studies with appropriate follow-up prior to its more widespread application.19

The aim of the present randomized study was to investigate the effectiveness of TM with the option of video consultations on number of hospital admissions for COPD in patients with severe and very severe COPD recruited from respiratory outpatient clinics.

Materials and methods

Participants

In a randomized controlled trial, we recruited patients from four hospitals with specialized pulmonary wards in Copenhagen (Hvidovre Hospital, Amager Hospital, Herlev Hospital, and Bispebjerg Hospital). The target population was patients with stable severe and very severe COPD at high risk of exacerbations and hospital admissions. Patients were eligible for the study, if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: 1) COPD defined according to the GOLD criteria2 (post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity <0.7), 2) post-bronchodilator FEV1 <60% of predicted value, 3) hospital admission due to COPD exacerbation within the previous 36 months and/or treated with LTOT for at least 3 months, 4) regular scheduled visits to the respiratory outpatient clinics, 5) COPD judged by the study staff as the main cause of disability, and 6) residents in one of the six municipalities in the Copenhagen area and in the catchment area of one of the four recruiting hospitals. The exclusion criteria were the following: 1) an exacerbation of COPD within the 3 weeks prior to enrollment requiring a change in medical treatment, 2) not willing to give informed consent for participating in the study, 3) unable to use a tablet computer, 4) planned vacation or other stay outside the catchment area for 2 weeks or more during the study period, 5) unable to participate due to language barrier or cognitive disorders, and 6) not possible to establish a working telephone line. Patients were withdrawn from the study, if they no longer wished to participate, or if they moved out of the hospitals catchment areas. In case of hospital admission, patients continued in the study immediately after discharge from the hospital

Patient selection and randomization

Between November 2013 and April 2014, we identified 560 patients who met the clinical inclusion and not the exclusion criteria. Of the identified patients, 279 (49.8%) patients declined to participate. The remaining 281 patients gave informed consent to participate in the trial and were randomized to either TM or usual care (control group) with a 1:1 allocation using randomized blocks of four (via numbered envelopes) for 6 months. Patients recruited and randomized to either TM or usual care at each of the hospitals were divided into three groups: Group 1: ≥hospital admission for COPD in the previous year; Group 2: ≥hospital admission for COPD in the past 3 years, but not within the year prior to enrollment; and Group 3: LTOT regardless of the number of admissions for COPD in previous years. Block randomization was used to ensure that equal numbers of patients from the three groups were allocated to TM and usual care.

Standard management of COPD

All patients enrolled in the trial were managed according to national and international guidelines, including outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with COPD with FEV1 <50%pred and Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea score ≥320 and supported discharge to selected in-hospital patients to reduce the risk of early readmission.21

Control group

Patients on LTOT were managed either by respiratory nurses at home or in the outpatient clinic depending on the patient’s mobility. All other patients were seen for scheduled visits at the outpatient clinics once or twice a year and for unscheduled visits as required. Patients were informed that they could contact the staff at the outpatient clinic weekdays between 9 am and 3 pm, if they had acute respiratory problems.

Tele monitoring

The TM equipment comprised a tablet computer with a web camera, a microphone, and measurement equipment (spirometer, pulse oximeter, and bathroom scale). Besides, patients reported changes in dyspnea, sputum color, volume, and purulence. The observations were transferred to a call center at each participant’s local hospital and automatically categorized and prioritized (ie, green–yellow–red-coded). The call centers were open weekdays between 9 am and 3 pm and were staffed by a specially trained respiratory nurse. The nurse could confer the patients with a specialist in respiratory medicine at the hospital if values were alarming (a single measurement with red code or two consecutive measurements with yellow code); the patient was contacted by the respiratory nurse.

Measurements without video consultation were taken three times a week for the first 4 weeks and afterward once weekly. Video consultation with spirometry was performed once a week during the first 4 weeks of the study period and then once monthly. Patients were free to perform additional measurements at any time or phone the call center during opening hours, if they considered it necessary. Depending on the situation, an unscheduled video consultation could be arranged if necessary. The measurements were recorded in a secured database to which the patient’s general practitioner and the municipal’s social and health workers had access.

Patients randomized to the TM group were not seen at regular scheduled visits at the outpatient clinics, but unscheduled visits were arranged if the TM consultation was considered inadequate by the health care professional.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of hospital admissions for COPD in the 6-month study period.

Secondary effect parameters were number of all-cause hospital admissions, time to first hospital admission, time to first hospital admission caused by exacerbation in COPD, number of visits to emergency rooms, number of visits to the outpatient clinic (respiratory departments and nonrespiratory departments, respectively), number of exacerbations in COPD requiring treatment with systemic steroid and/or antibiotics but not admission to hospital (according to the patient and patient’s medical record, including prescriptions), length of hospital admissions (days), and all-cause mortality.

The Danish National Registry of Patients and the Danish National Registry of Deaths provided information on all hospital admissions, visits to emergency rooms, and vital status during the 6-month study period (tracked by each individual’s unique personal number from the Danish Central Person Register).

The study is approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-4-2013-052).

Sample size calculations

We estimated that 125 participants in each arm would allow us to detect a difference in the primary outcome variable, that is, number of hospital admissions for COPD in the 6-month study period, of 40% with a 90% power, using a significance level of 5%.

Measurements

The self-reported MRC dyspnea score that rates breathlessness on a scale from 1 (no dyspnea) to 5 (breathless while washing and dressing or too breathless to leave the house) was used for assessing breathlessness.20

We used Charlson Comorbidity Index scores to assess level and severity of comorbidity in the study cohort.22 The Charlson Comorbidity Index score is calculated as the sum of points (on a scale from 1 to 6) assigned to each of 19 diseases.22 Information on comorbid diseases was obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with the statistical package SPSS version 19.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics). The χ2, two sample t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used, as appropriate, for comparisons between groups. A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank statistics was applied to estimate a model for time to first event of interest, for example, hospitalization due to exacerbation in COPD.

Subgroup analyses

For the outcomes of interest, subgroup analyses were performed based on sex, current smoking, LTOT, and hospital admission for COPD exacerbation in the year prior to enrollment, as these factors may possibly affect the impact of the intervention.23,24

Results

Baseline characteristics

The majority of patients enrolled in the study had severe COPD, with 207 patients (85.7%) having an FEV1 <50%pred, 148 patients (52.7%) with MRC score >3, 126 patients (44.9%) having at least one hospital admission for COPD in the year prior to enrollment, and 75 patients (26.7%) on LTOT (Table 1). More females were allocated to TM, whereas more never smokers were allocated to the control group. Comparing other baseline characteristics between the two treatment groups revealed no significant differences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the patients (n=281) enrolled in the tele health care study divided according to the group assignment

| Tele monitoring, N=141 | Controls, N=140 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females, N (%) | 86 (61%) | 63 (45%) | 0.007 |

| Age, years | 69.8 (9.0) | 69.4 (10.1) | 0.75 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.9 (6.3) | 26.9 (7.0) | 0.013 |

| FEV1 %pred | 34.9 (13.3) | 33.8 (12.0)a | 0.48 |

| MRC dyspnea score, mean (range) | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.7 (1–5) | 0.09 |

| Current smokers, N (%) | 35 (24.8%) | 47 (33.6%) | 0.10 |

| Pack years, mean (range) (N=133/116)b | 42.9 (0–210) | 41.0 (0–110) | 0.72 |

| Long-term oxygen therapy, N (%) | 37 (26.2%) | 38 (27.1%) | 0.86 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.70 (1.49) | 1.96 (1.51) | 0.13 |

| Living alone, % | 57.9% | 52.2% | NS |

| Hospital admissions for COPD exacerbation in the year prior to enrollment, mean (range) | 1.41 (0–7) | 1.22 (0–23) | 0.61 |

| Medication for COPD, N (%) | |||

| Oral prednisolonec | 10 (7.1%) | 14 (10.0%) | 0.68 |

| Roflumilast | 8 (5.7%) | 5 (3.6%) | 0.39 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 129 (91.5%) | 128 (91.4%) | 0.57 |

| Long-acting antimuscarinic agents | 131 (92.9%) | 120 (85.7%) | 0.99 |

| Long-acting β2-agonists | 134 (95.0%) | 136 (97.1%) | 0.54 |

Notes: Values are mean (and standard deviation) unless otherwise specified. All P-values are comparisons between the TM and control group.

Data missing for one patient;

data missing for patients 8 and 24, respectively.

maintenance therapy.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MRC, Medical Research Council; TM, tele monitoring; NS, not significant.

Study completion and withdrawals

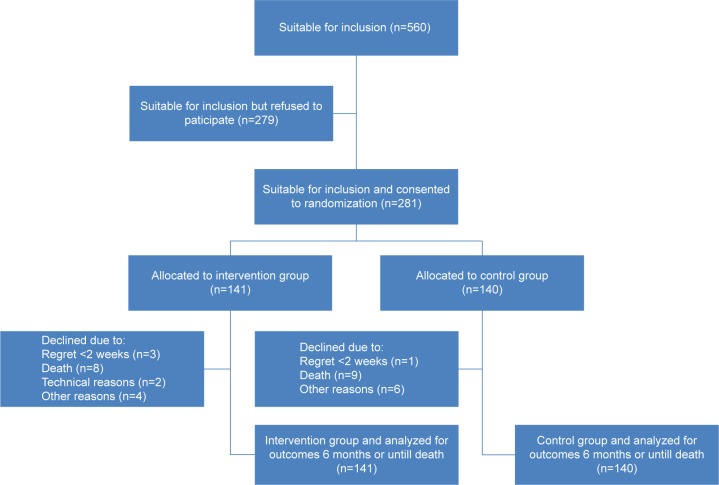

Four patients (three in the TM group) withdrew their consent within the first 2 weeks of the study period. Seventeen patients died during the study period, and another 12 patients dropped out for various reasons (Figure 1). No significant differences in drop-out rates (P=0.79) or mortality were found between the groups (P=0.87).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients with COPD identified as eligible for inclusion into the study investigating the effect of add-on tele health care, including video consultations, to standard care on hospital admissions for COPD.

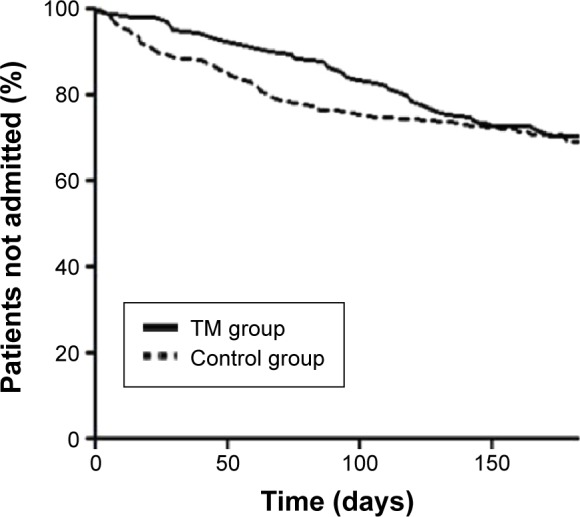

Hospital admissions for COPD

Analyzing the data with regard to the primary outcome did not reveal any significant difference in number of hospital admissions for COPD in the two groups, that is, TM vs control group (Table 2), and likewise, no significant difference was found in the proportion of patients experiencing an acute exacerbation of COPD in the two groups (Figure 2) or time to first hospitalization for COPD.

Table 2.

Frequency and characteristics of acute exacerbations, hospital admissions, and visits to emergency rooms and outpatient clinics for tele monitored patients and controls

| Tele monitoring, N=141 | Controls, N=140 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital admission for COPD exacerbation, mean (range) | 0.55 (0–5) | 0.54 (0.4) | 0.74 |

| All cause hospital admissions, mean (range) | 1.19 (0–12) | 1.31 (0–9) | 0.28 |

| At least one hospitalization (any cause), % | 46.8% | 51.4% | 0.44 |

| Length of stay, all-cause hospital admissions (days), mean (range) | 5.35 (0–71) | 5.29 (0–53) | 0.38 |

| At least one COPD exacerbation requiring hospital admission, % | 29.1% | 31.4% | 0.67 |

| Length of stay, COPD hospital admissions (days), mean (range) | 1.76 (0–52) | 2.02 (0–31) | 0.51 |

| Exacerbation of COPD not requiring hospital admission,a mean (range) | 1.21 (0–17) | 0.73 (0–8) | 0.001 |

| At least one exacerbation of COPD not requiring hospitalizationa | 58.2% | 37.1% | <0.001 |

| Visits to the emergency room, mean (range) | 0.11 (0–3) | 0.16 (0–2) | 0.12 |

| Visits to the respiratory outpatient clinic, mean (range) | 0.26 (0–3) | 0.99 (0–7) | <0.001 |

| Visits to nonrespiratory outpatient clinics, mean (range) | 1.34 (0–12) | 1.41 (0–10) | 0.43 |

Note:

An exacerbation was defined as a worsening of COPD symptoms requiring treatment with a rescue course of systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics.

Figure 2.

Hospital admission for COPD during the 6-month study period for patients randomized to tele health care + standard care (TM group, n=141) vs standard care (control group, n=140).

Abbreviation: TM, tele monitoring.

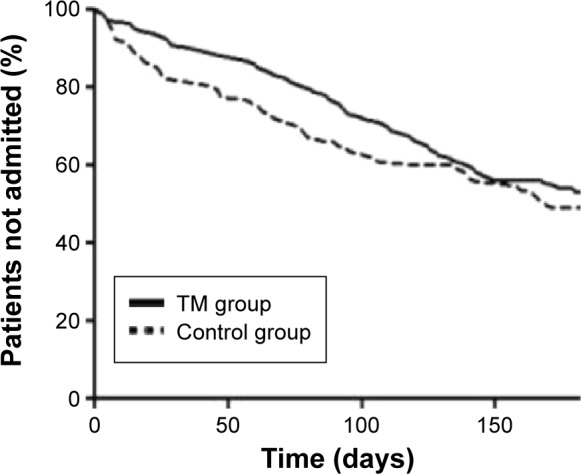

All-cause hospital admissions

Comparing the two groups revealed no significant difference in the total number of hospital admissions (Figure 3), number of patients having any admission to hospital, time to first hospitalization, or visits to the emergency room during the study period (Table 2).

Figure 3.

All-cause hospital admission during the 6-month study period for patients randomized to tele health care + standard care (TM group, n=141) vs standard care (control group, n=140).

Abbreviation: TM, tele monitoring.

Exacerbations of COPD not requiring hospital admission

The mean number of exacerbations not requiring hospitalization but treated with a course of oral corticosteroid and/or antibiotics was significantly higher for the patients in the TM group compared with the control group (P<0.001), whereas the control group had more visits to outpatient clinics (Table 2).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses stratified by sex, current smoking, LTOT, or hospital admission for COPD exacerbation in the year prior to randomization revealed no statistical significant differences the two groups.

Characteristics at the end of the study period

At the end of the study period, significantly more patients in the TM groups were nonsmokers (76.6% vs 58.1%, P=0.002), whereas the proportion of patients having participated in a pulmonary rehabilitation program in the study period only reached borderline significance (38.0% vs 27.0%, P=0.068).

Communication with patients assigned to telemedicine

Each patient was scheduled for seven video consultations during the study period, and 100 (82.6%) patients participated in at least six consultations. Data on unscheduled communication with the health care professionals during the study period was missing for three of 124 patients who completed the study. A total of 12 patients had unscheduled video consultations (more than one in only one patient). Phone or email was used for communication in 91 (75.2%) of the patients (mean 3.3 contacts per patient).

Discussion

The present randomized clinical trial revealed that TM with close contact between the patient and the health care providers at the hospital and the possibility of monitoring for early signs of COPD exacerbations leads to an increase in number of exacerbations treated outside the hospital setting, whereas TM had no significant impact on hospitalizations or mortality.

Have we included the right patients?

Similar to other studies, a significant number of eligible patients refused to participate in our study.14,25 However, we did manage to include the planned number of patients with the a priori expected number of exacerbations in COPD leading to hospital admission during the 6-month study period.

Vitacca et al have previously shown that TM was effective in preventing hospital admissions in severe and frail chronic respiratory failure patients requiring home oxygen therapy and/or mechanical ventilation.14 In addition, a tendency toward reduced hospitalization rate has been reported from two small studies comprising a high proportion of patients on LTOT.12,13 Although close to 30% of the patients included in the present study were on LTOT, we were unable to demonstrate an effect of TM on hospital admissions in this subgroup of patients.

Did we have all important components in our intervention?

In addition to early identification of exacerbations, and by that facilitating early treatment and prevention of hospital admissions, the aim of TM is to support patient empowerment and to optimize the management of COPD, also to encourage and help patients to quit smoking and do daily physical exercising.

Although not a predefined outcome of interest, we found that significantly more patients in the TM group were nonsmokers and a tendency toward more patients having participated in pulmonary rehabilitation compared with controls at the end of the study period.

TM combined with pulmonary rehabilitation has been associated with a reduction in hospital admissions.7,26 However, as the positive effect of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD is well established, we believe that participation in such a program should be offered to all patients with more severe COPD, and referral or not for pulmonary rehabilitation was therefore not part of the intervention in the present trial. Furthermore, education in disease self-management in addition to treatment action plans was not part of the intervention, as we believe that studies addressing this intervention have produced too conflicting results, and, therefore, that a clinical trial addressing this aspect of COPD management may seem more appropriate.26–28

General practitioners involvement in TM for COPD

To include patients with high risk of hospitalization, we recruited patients from our outpatient clinics, and general practitioners were not a part of the TM intervention. In contrast, two British studies have recruited patients from general practitioners.8,15 The Whole System Demonstration included 3,154 patients, where 1,525 had COPD and the remaining patients had either diabetes or chronic heart failure. After 1 year, the admission rate was significantly lower in the TM group compared with controls (1.17 vs 0.96). Unfortunately, analyses are not given for the subgroup of patients with COPD, and besides, the positive effect of TM was almost entirely caused by an abrupt increase in hospitalization among the controls.15

The Scottish study by Pinnock et al enrolled 256 patients with COPD with characteristics closely resembling our patients, also with regard to hospital admissions during the study period.8 Similar to our study, Pinnock et al were unable to demonstrate any positive effect of TM on hospitalizations. In contrast to the Scottish study,8 video consultations were planned regularly in our study to improve the clinical assessment and, also, to make the patient comfortable with the equipment so it could be used if the patient experienced a worsening of their disease. However, the preferred communication for the patients in our study was either phone or email and not video consultations. As stated previously by Pinnock et al,8 the positive effect of TM seen in previous trials could thus be due to enhancement of the underpinning clinical service rather than the TM.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include that we have included a large number of patients with a sufficient number of admissions to see a clinically relevant effect of an intervention, and that no patients were lost to follow-up.

The limitations of our study are the fact that our call centers were only operating Monday to Friday in the daytime, and that we do not have data on the enrolled patients’ number of visits to their GP during the study period.

Conclusion

We found that TM in addition to usual care in outpatient clinics did not reduce hospital admissions, but TM may be an alternative to visits at the respiratory outpatient clinic. More studies are needed to establish the optimal follow-up strategy of patients with COPD including the role of TM.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the NETKOL group (Pia Andersen, Lisbeth Østergaard, Christine Lilliedahl, Torben Lage Frandsen, Jo-Ann Ramsrud Jensen, Lene Nissen, Marie-Louise Pagh Søndberg, Tanja S. Hansen, and Zofia Mikolaczyk) for data sampling and enthusiastic collaboration throughout the study period and also Jan Sørensen for help with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interests in relation to the present article.

References

- 1.Eriksen N, Vestbo J. Management and survival of patients admitted with an exacerbation of COPD: comparison of two Danish patient cohorts. Clinl Respir J. 2010;4(4):208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2009.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundhedskoordinationsudvalget . Forløbsprogram for KOL i Region Hovedstaden. Copenhagen: Capital Region of Denmark; 2009. In Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wootton R. Twenty years of telemedicine in chronic disease management – an evidence synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(4):211–220. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schou L, Ostergaard B, Rydahl-Hansen S, et al. A randomised trial of telemedicine-based treatment versus conventional hospitalisation in patients with severe COPD and exacerbation – effect on self-reported outcome. J Telemed Telecare. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1357633X13483255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorknaes AD, Madsen H, Hallas J, Jest P, Hansen-Nord M. Nurse tele-consultations with discharged COPD patients reduce early readmissions – an interventional study. Clin Respir J. 2011;5(1):26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2010.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinesen B, Haesum LK, Soerensen N, et al. Using preventive home monitoring to reduce hospital admission rates and reduce costs: a case study of telehealth among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(4):221–225. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.110704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6070. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koff PB, Jones RH, Cashman JM, Voelkel NF, Vandivier RW. Proactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1031–1038. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00063108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL, Pagliari C, Car J, Sheikh A. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):Cd007718. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007718.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz J, Brooks D, Marques A. Home telemonitoring in COPD: a systematic review of methodologies and patients’ adherence. Int J Med Inf. 2014;83(4):249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jodar-Sanchez F, Ortega F, Parra C, et al. Implementation of a telehealth programme for patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with long-term oxygen therapy. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(1):11–17. doi: 10.1177/1357633X12473909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiolo C, Mohamed EI, Fiorani CM, De Lorenzo A. Home telemonitoring for patients with severe respiratory illness: the Italian experience. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(2):67–71. doi: 10.1258/135763303321327902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitacca M, Bianchi L, Guerra A, et al. Tele-assistance in chronic respiratory failure patients: a randomised clinical trial. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(2):411–418. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00005608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamad GA, Crooks M, Morice AH. The value of telehealth in the early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a prospective observational study. Health Informatics J. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1460458214564434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoddart A, van der Pol M, Pinnock H, et al. Telemonitoring for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cost and cost-utility analysis of a randomised controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1357633X14566574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell JE, McClean S, FitzGibbon F, Tate S. A randomised clinical trial of the effectiveness of home-based health care with telemonitoring in patients with COPD. J Telemed Telecare. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1357633X14566575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein RS, O’Hoski S. Telemedicine in COPD: time to pause. Chest. 2014;145(5):945–949. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, Wood CH. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. British medical journal. 1959;2(5147):257–266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5147.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.British Thoracic Society Guideline Development Group Intermediate care – Hospital-at-Home in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: British Thoracic Society guideline. Thorax. 2007;62(3):200–210. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husebo GR, Bakke PS, Aanerud M, et al. Predictors of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – results from the Bergen COPD cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pare G, Sicotte C, St-Jules D, Gauthier R. Cost-minimization analysis of a telehomecare program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12(2):114–121. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(5):585–591. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE, et al. Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):890–896. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1579OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):673–683. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]