Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to use health administrative and environmental data to quantify the effects of ambient air pollution on health service use among those with chronic diseases. We hypothesised that health service use would be higher among those with more exposure to air pollution as measured by the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI).

Setting

Health administrative data was used to quantify health service use at the primary (physician office visits) and secondary (emergency department visits, hospitalisations) level of care in Ontario, Canada.

Participants

We included individuals who resided in Ontario, Canada, from 2003 to 2010, who were ever diagnosed with one of 11 major chronic diseases.

Outcome measures

Rate ratios (RR) from Poisson regression models were used to estimate the short-term impact of incremental unit increases in AQHI, nitrogen dioxide (NO2; 10 ppb), fine particulate matter (PM2.5; 10 µg/m3) and ozone (O3; 10 ppb) on health services use among individuals with each disease. We adjusted for age, sex, day of the week, temperature, season, year, socioeconomic status and region of residence.

Results

Increases in outpatient visits ranged from 1% to 5% for every unit increase in the 10-point AQHI scale, corresponding to an increase of about 15 000 outpatient visits on a day with poor versus good air quality. The greatest increases in outpatient visits were for individuals with non-lung cancers (AQHI:RR=1.05; NO2:RR=1.14; p<0.0001) and COPD (AQHI:RR=1.05; NO2:RR=1.12; p<0.0001) and in hospitalisations, for individuals with diabetes (AQHI:RR=1.04; NO2:RR=1.07; p<0.0001) and COPD (AQHI:RR=1.03; NO2:RR=1.09; p<1.001). The impact remained 2 days after peak AQHI levels.

Conclusions

Among individuals with chronic diseases, health service use increased with higher levels of exposure to air pollution, as measured by the AQHI. Future research would do well to measure the utility of targeted air quality advisories based on the AQHI to reduce associated health service use.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of a large population-based data set and inclusion of multiple major chronic diseases and conditions over an 8-year period.

Exposure measurements were captured by multiple monitoring stations on an hourly basis, providing a thorough data set of air quality and pollutants.

Use of fixed exposure monitoring sites to infer exposures of individuals across relatively large geographic areas (Local Health Integration Networks) may lead to potential misclassification of exposure.

Lack of individual level data may have overestimated or ‘double counted’ health service use among individuals with more than one chronic disease or when individuals were admitted to hospital through the emergency department and were counted as both the emergency department and hospital admission encounters.

We have not analysed other pollutants, such as carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide, which may be important morbidity factors in certain regions.

Introduction

Air pollution poses measurable adverse health effects across populations and thus, is increasingly identified as a significant public health issue. The Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) is a composite measure of air quality (nitrogen dioxide (NO2), fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone (O3)), specifically developed to measure the impact of air pollution on human health.1–3 Previous research has used population-based data to examine the short-term impact of air pollution on asthma-related morbidity and has shown an association between increased daily maximum AQHI and increased asthma health services use on the same day and on the following 2 days.1

The impact of air pollution on health service use is relatively well defined for pulmonary and cardiovascular disease; however, the acute effects in individuals with other chronic conditions are less well known. Recent studies have suggested that other chronic diseases may also be aggravated by air pollution, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease (including heart attack and stroke), cancer and diabetes.4–12 The objective of this study was to use the AQHI to quantify the impact of exposures to poor air quality on short-term morbidity measured by health service use for individuals with 11 major chronic diseases. Quantifying effects of ambient air pollution on health service use in vulnerable populations with chronic diseases will assist in informing public policy on air quality standards.

Methods

Study population

We used health administrative data from Ontario, Canada—a province with a diverse multicultural population of approximately 13 million in 2010 and universal health system access for all residents. We included individuals aged 0–99 years if they had ever been diagnosed with any of these 11 chronic diseases: asthma, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, angina, acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, lung cancer and non-lung cancers. We used previously validated algorithms with International Classification of Disease codes to identify these diseases and conditions (see online supplementary material, S1).

Exposure measures: air quality

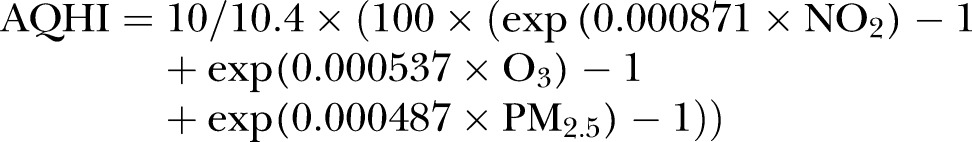

The Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change provided hourly AQHI and air pollutant measures (NO2, PM2.5, O3) from 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2010; these air quality measurements were collected by 42 fixed-site air quality monitors located across 33 cities in 14 Local Health Integration Networks in Ontario, administered by the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. These monitors made continuous measurements of common air pollutants near real time. Online supplementary material, S2 provides details about quality control conducted by the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. The AQHI is calculated using the following formula:

|

Units are parts per billion (ppb) for NO2 and O3, and micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3) for PM2.5.13 The AQHI presents a simple scale ranging from 1 to 10+ where 1 represents good air quality and a low health risk, and 10 represents poor air quality and a high-health risk (see online supplementary material, S2).We calculated daily 1 h maximum values of AQHI, NO2, PM2.5 and O3 for each Local Health Integration Network. One-hour maximum values were used, as it has been suggested in the literature that these provide the most significant results when predicting short-term health effects, compared to mean and median values.14

Outcome measures: health services use

We used total daily all-cause health service use to measure acute health morbidities for individuals with chronic diseases. We obtained these data from four health administrative databases housed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences: the Ontario Health Insurance Plan Database contains information on fee-for-service billings for physician services rendered; the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System contains data for emergency department visits; the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database records the primary and secondary diagnoses for all hospitalisations; the Ontario Registered Persons Database includes information on sex, birth date and region of residence. We calculated all-cause rates of health service use per 1000 disease-specific populations.

Definition of covariates

We adjusted for potential confounding variables in our multivariable analysis. These variables included age group (10-year age groups), sex, region of residence, socioeconomic status, day of the week, temperature, season and year of data (2003–2010). We examined individuals aged 20+ years in all analyses; however, we also included individuals aged 0–19 years in the analysis of asthma and diabetes, excluded those aged under 30 years in the analysis of COPD and excluded those aged under 40 years in the analysis of congestive heart failure (see details in online supplementary materials, S1). We categorised region of residence according to Local Health Integration Network. We inferred socioeconomic status from neighbourhood income quintiles, based on census data. We categorised seasons as follows: spring (March to May), summer (June to August), fall (September to November) and winter (December to February). There was less than 0.5% missing data in demographic variables and 10% in income quintiles; missing categories were excluded from the regression analyses. Missing daily temperatures (less than 1%) were substituted by the mean temperature of the respective month.

Statistical analysis

We calculated yearly distributions of the daily maximum values of the AQHI and pollutants, as well as prevalence and health service use for the chronic diseases from 2003 to 2010. We used Poisson regressions to examine the associations between air quality and health service use; we examined immediate effects with a time lag of 0, 1 and 2 days. The unit of analysis for health service use was the number of outpatient claims or emergency department or hospital admissions on day 0. We included offset terms for the disease-specific populations and adjusted for confounders. We used rate ratios (RR) with p values to calculate the risk of short-term disease-specific health service use associated with acute exposure to poor air quality.15 We checked for overdispersion and violations of Poisson assumptions by plotting residuals versus mean exposure level.15 We used Pearson’s χ2 test to assess model goodness-of-fit. To calculate the expected increase in health service use on days with an AQHI of 3, 6 and 10 (chosen based on AQHI health advisory category cut-points for low risk, medium risk and high risk, respectively), we multiplied the disease-specific daily average health service use rates from the Poisson models by the average disease prevalence. We used SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) to perform the analyses.16

Results

Air quality trend

The distributions of the mean daily maximum AQHI, NO2, PM2.5 and O3 by year and season are shown in online supplementary material, table S3. For 2003–2010, average measures±SDs were AQHI: 3.45±1.19, NO2: 24.39±12.41 ppb, PM2.5: 13.93±9.53 µg/m3 and O3: 39.57±14.15 ppb, with a general improvement in all air quality metrics over time. Air quality and pollutant values varied seasonally: AQHI was highest in the spring (3.79±1.09) and lowest in the fall (3.02±1.13); NO2 was highest in winter (27.98±12.58 ppb) and lowest in summer (19.71±10.14 ppb); PM2.5 and O3 were highest in summer (PM2.5: 18.06±11.31 µg/m3; O3: 48.63±15.53 ppb) and lowest in winter (PM2.5: 11.12±6.77 µg/m3; O3: 30.76±7.12 ppb). Air quality and air pollutant values also differed by geographic region, with Ontario's smallest and most populous Local Health Integration Network having the highest average AQHI (4.05±1.27) and NO2 (33.18±12.18 ppb), while Ontario's largest and least populous Local Health Integration Network had the lowest average AQHI (2.87±0.92), PM2.5 (10.57±7.04 µg/m3) and O3 (35.98±9.85 ppb).

Distributions of chronic diseases and morbidities

Table 1 shows the distributions of the chronic diseases and associated all-cause health service use per 1000 disease population. Hypertension (24.9%) and asthma (13.3%) had the highest disease prevalence. Individuals with lung cancer had the highest emergency department visits and hospitalisation rates (209.6 and 330.6 per 1000, respectively), while individuals with diabetes had the highest outpatient visit rate (2805.9 per 1000). Chronic disease prevalence rates from 2003 to 2010 are presented in online supplementary material, figure S5.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of chronic diseases and health services use, Ontario, averaged over 2003–2010

| Number ever |

Health services use* |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed† |

Outpatient visits |

ED visits |

Hospital admissions |

|||||

| Disease categories | N | Rate‡ | N | Rate* | N | Rate* | N | Rate* |

| Hypertension | 2 395 192 | 24.9 | 3 625 230 | 1513.5 | 38 146 | 15.9 | 21 089 | 8.8 |

| Asthma | 1 690 973 | 13.3 | 842 305 | 498.1 | 62 599 | 37.0 | 6 713 | 4.0 |

| Non-lung cancers | 1 096 599 | 11.4 | 1 985 132 | 1810.3 | 27 245 | 24.8 | 73 834 | 67.3 |

| Angina | 946 575 | 9.8 | 475 448 | 502.3 | 17 855 | 18.9 | 11 181 | 11.8 |

| Diabetes | 915 458 | 7.2 | 2 568 707 | 2805.9 | 147 385 | 161.0 | 17 461 | 19.1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 615 540 | 7.8 | 495 663 | 805.2 | 36 868 | 59.9 | 21 334 | 34.7 |

| Stroke | 450 315 | 4.7 | 665 649 | 1478.2 | 16 214 | 36.0 | 12 658 | 28.1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 212 790 | 3.5 | 444 022 | 2086.7 | 28 561 | 134.2 | 19 017 | 89.4 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 204 800 | 2.1 | 304 261 | 1485.7 | 5 253 | 25.7 | 26 930 | 131.5 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 147 939 | 1.5 | 95 695 | 646.9 | 6 678 | 45.1 | 21 089 | 142.6 |

| Lung cancer | 16 711 | 0.2 | 2 121 | 126.9 | 3 503 | 209.6 | 5 525 | 330.6 |

*All-cause health services utilisation rate per 1000 disease-specific prevalent population.

†Asthma and diabetes included all ages; COPD ages 30+ years, chronic heart failure ages 40+ years, all others 20+ years.

‡Rate per 100 population.

ED, emergency department.

Associations of air quality measures and disease morbidities

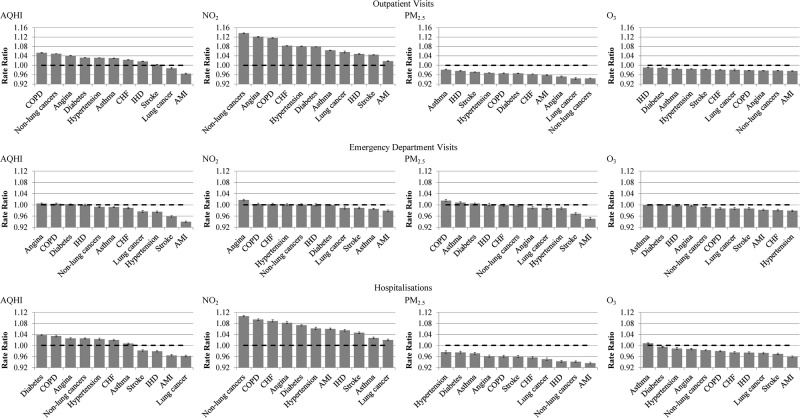

Table 2 and figure 1 show the results of the disease-specific multivariable Poisson regressions that modelled the association between AQHI, air pollutants and health service use on day 0 of exposure (see day 1 and 2 of exposure in online supplementary material, table S4a and S4b). The risk of individual pollutant was adjusted for the presence of other pollutants. None of the regression models violated model assumptions. Overall, the increase in the rate of outpatient visits for each unit increase in the same-day AQHI and each unit (10-ppb) increase in daily maximum NO2 (adjusted for PM2.5 and O3) varied from 1% to 14%. Those with non-lung cancers (AQHI:RR=1.05; NO2:RR=1.14) or COPD (AQHI:RR=1.05; NO2:RR=1.12) had the greatest increase in same-day outpatient visits. Increase in rate of same-day hospitalisation was highest among those with diabetes (AQHI RR=1.04; NO2:RR=1.07) and COPD (AQHI RR=1.03; NO2:RR=1.09). The increase in rate of same-day emergency department visits was relatively small. The impact on health service use remained 1 and 2 days after the measured peak AQHI and NO2.

Table 2.

Risk of health services use (claim or admission) by AQHI and pollutants on day 0 of exposure; each pollutant is adjusted for the other two pollutants

| Disease categories (In alphabetical order) | Outpatient visits |

ED visits |

Hospitalisations |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate ratio* | L95% | U95% | p Value | Rate ratio* | L95% | U95% | p Value | Rate ratio* | L95% | U95% | p Value | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| Angina | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | <0.0001 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | <0.0001 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.09 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.0179 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Asthma | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.07 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | <0.0001 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.7534 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | <0.0001 |

| Non-lung cancers | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | <0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.14 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.5871 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.11 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.3745 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.0261 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.7619 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.06 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.0007 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.04 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.0338 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.10 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.0013 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.3093 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.08 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.5334 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.2714 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.07 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.8059 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.8365 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.06 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.6955 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.3718 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Lung cancer | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.06 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | ||||||||||||

| AQHI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| NO2 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.05 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.05 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

*The Risk Ratios were obtained from Poisson Regressions and these correspond to increase/decrease in risk of the respective health services use per unit increase in AQHI or per 10-unit increase in the air pollutants. All Risk Ratios were adjusted for age groups, sex, seasons, temperature, day of week, years, Local Health Integration Network and income quintiles.

L95%, lower bound of 95% CI; U95%, upper bound of 95% CI.

AQHI, Air Quality Health Index; ED, emergency department; NO2 nitrogen dioxide; PM2.5 fine particulate matter; O3, ozone.

Figure 1.

Risk* of health services use by pollutants on day 0 of exposure: AQHI, NO2, PM2.5 and O3. * The Rate Ratios were obtained from Poisson Regressions and these correspond to increase/decrease in risk of the respective health services use per unit increase in AQHI and per 10-unit increase in each of NO2, PM2.5 and O3. All Rate Ratios were adjusted for age groups, sex, day of the week, temperature, seasons, years, Local Health Integration Network and income quintiles. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Table 3 shows a translation of the population data into predicted daily rates and daily expected all-cause health service use among populations with each of the chronic conditions on days with a maximum AQHI of 6 (medium health risk) or 10 (high), as compared to days with a maximum AQHI of 3 (low health risk). Given that the increase in the rate of emergency department visits was small (see table 2), we focused on the per cent change in outpatient visits and hospital admissions. The highest per cent changes in outpatient visits on a day with a maximum AQHI of 10 were predicted in COPD, non-lung cancers and angina (43.9%, 39.6% and 32.4%, respectively). The highest per cent changes in hospitalisations were predicted in diabetes, COPD and angina (29.7%, 26.7% and 19.4%, respectively). The greatest increase in expected counts of outpatient visits and hospitalisations on a day with a maximum AQHI of 10 was predicted in hypertension (3862 more expected outpatient visits) and non-lung cancers (49 more expected hospitalisations), respectively. Overall, the increase in air pollution-attributable outpatient visits comparing moderate and high-risk air quality days to low-risk days amounted to a total of 6052, and 15 301 visits per day, respectively.

Table 3.

Predicted daily health services use based on AQHI and pollutant levels

| AQHI=3 |

AQHI=6 |

AQHI=10 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Low-health risk) |

(Moderate-health risk) |

(High-health risk) |

||||||

| Predicted daily rate* | Expected number of visits† |

Predicted daily rate* | Expected number of visits† |

Per cent change‡ | Predicted daily rate* | Expected number of visits† |

Per cent change‡ | |

| Outpatient visits (sorted by highest to lowest expected no. of visits) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 5.83 | 15 834 | 6.41 | 17 387 | 9.8 | 7.26 | 19 697 | 24.4 |

| Diabetes | 10.72 | 12 236 | 11.79 | 13 450 | 9.9 | 13.37 | 15 258 | 24.7 |

| Non-lung cancers | 5.53 | 7 437 | 6.38 | 8 581 | 15.4 | 7.72 | 10 384 | 39.6 |

| Asthma | 1.80 | 3 366 | 1.97 | 3 681 | 9.3 | 2.21 | 4 146 | 23.2 |

| Stroke | 5.21 | 2 648 | 5.24 | 2 666 | 0.7 | 5.29 | 2 691 | 1.6 |

| COPD | 2.41 | 1 660 | 2.82 | 1 940 | 16.9 | 3.47 | 2 388 | 43.9 |

| Angina | 1.51 | 1 544 | 1.70 | 1 741 | 12.8 | 2.00 | 2 045 | 32.4 |

| Congestive heart failure | 6.19 | 1 412 | 6.63 | 1 512 | 7.1 | 7.26 | 1 657 | 17.4 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5.18 | 1 138 | 5.43 | 1 193 | 4.9 | 5.79 | 1 271 | 11.8 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.88 | 307 | 1.69 | 276 | −10.3 | 1.46 | 238 | −22.4 |

| Lung Cancer | 0.46 | 9 | 0.45 | 8 | −3.8 | 0.42 | 8 | −8.5 |

| Hospitalisations (sorted by highest to lowest expected number of visits) | ||||||||

| Non-lung cancers | 0.19 | 250 | 0.20 | 270 | 7.9 | 0.22 | 299 | 19.3 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 0.44 | 97 | 0.42 | 91 | −6.1 | 0.38 | 84 | −13.6 |

| Diabetes | 0.06 | 73 | 0.07 | 82 | 11.8 | 0.08 | 95 | 29.7 |

| COPD | 0.09 | 64 | 0.10 | 71 | 10.7 | 0.12 | 81 | 26.7 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0.40 | 65 | 0.36 | 59 | −10.3 | 0.31 | 51 | −22.4 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.24 | 54 | 0.25 | 58 | 6.1 | 0.27 | 63 | 14.8 |

| Stroke | 0.09 | 47 | 0.09 | 44 | −5.3 | 0.08 | 41 | −11.8 |

| Angina | 0.03 | 32 | 0.03 | 34 | 7.9 | 0.04 | 38 | 19.4 |

| Asthma | 0.01 | 21 | 0.01 | 22 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 22 | 4.8 |

| Lung Cancer | 1.03 | 20 | 0.92 | 17 | −11.0 | 0.79 | 15 | −23.7 |

| Hypertension | 0.00 | 7 | 0.00 | 8 | 7.2 | 0.00 | 9 | 17.5 |

*Predicted daily average rates per 1000 population were obtained from the adjusted Poisson regression models.

†Expected counts were calculated by multiplying the predicted rates to the average disease prevalence (we used the Ontario disease-specific prevalence population presented in table 1).

‡Per cent change is calculated as compared to when AQHI=3.

AQHI, Air Quality Health Index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

To date, in magnitude and breadth, this is one of the largest time series analyses examining the impact of air quality on health. We examined the effects of health service use across an entire health system and we analysed all major chronic diseases over 8 years. Strategically, this study focused on the AQHI, an important national translational tool that distils the complexity of air quality science and health risk into a simple visual linear scale for individuals with chronic disease, healthcare providers and public health and environmental policymakers. This study demonstrated a consistent and quantifiable health risk based on the AQHI that may inform public health and environmental policy.

The WHO describes a pyramid of air pollution-attributable health impacts that includes subclinical effects, symptoms, health services utilisation and mortality,17 18 and the US Environmental Protection Agency has also concluded that PM2.5, O3 and NO2 are causal or likely causal factors for numerous cardiac and pulmonary health outcomes.10–12 Plausible mechanistic pathways have been described, including enhanced coagulation/thrombosis, a propensity for arrhythmias, acute arterial vasoconstriction, systemic inflammatory responses and the chronic promotion of atherosclerosis.19 Our findings strengthen and extend an understanding of the acute impact of air pollution on chronic diseases for which there is limited published evidence, in particular for diabetes, hypertension and malignancy.

Hypertension remains the worldwide leading risk factor for mortality. A number of studies have reported associations between air pollutants and hypertension, as well as between air pollutants and diabetes incidence and prevalence;20–24 however, few have demonstrated its impact on health-related morbidity. Szyszkowicz25 used a large administrative database in Canada, and measured the association between ambient air pollution and hypertension presentations to emergency department visits during a 10-year period. They reported significantly elevated risks of emergency department visits (4–6%) up to 3–6 days after peaked exposures to PM10, PM2.5, NO2 and SO2. Similarly, our study showed an 8% increase in same-day physician visits per 10 ppb increase in same-day peak NO2, the fifth highest ratio observed after non-lung cancers, angina, COPD and congestive heart failure. This finding may indicate that modest elevations in air pollutants worsen blood pressure control, consequently leading to higher outpatient health service use or alternatively, that hypertension is a sensitive surrogate marker for multiple comorbidities.

Despite a compelling body of literature confirming the health risk of various air pollutants on individuals with chronic disease, these risks are underappreciated by patients and seldom acted on by clinicians.26 The complexities of communicating air quality, its associated health risks, and actionable risk-reduction messages may be contributing to low physician and patient uptake. Our study extends prior research by evaluating a new method of reporting and advising clinicians and patients about air quality and its risks: the AQHI. The AQHI was designed to create a more direct link between air quality and health, and to present the index in a format that could easily communicate risk reduction to the general population.27 Using a format similar to the ultraviolet ray index that the general public is familiar with, the AQHI ‘translates’ air quality on a scale of 1–10 and attaches specific risk-reduction health messages. Hong Kong, with the number of air pollution-related deaths ranked eighth highest out of 193 countries in the world,28 has recently adopted AQHI for real-time monitoring and reporting. In December 2013, AQHI was commissioned by the Hong Kong government and a free smartphone AQHI application was made available from iTunes.29 Similar scalable communication strategies are being executed in Canada. The effectiveness of these strategies remains to be determined.

This study has several strengths, namely the use of a large population-based data set and inclusion of multiple major chronic diseases and conditions over an 8-year period. To date, very few published studies are of comparable magnitude. The use of large sample sizes allowed Poisson regression models to be fully adjusted for multiple potential confounders. Furthermore, exposure measurements were captured by multiple monitoring stations on an hourly basis, providing a thorough data set of air quality and pollutants. Our study also calculated the predicted daily rate and expected volume of health services use. These rates can be used by others to generate their respective expected health service use counts based on their local disease-specific prevalence population.

A few limitations are worth noting. First, the use of fixed exposure monitoring sites to infer exposures of individuals across relatively large geographic areas (Local Health Integration Networks) may lead to potential misclassification of exposure—namely, the Berkson error. However, it has been shown that with exposure measured on a numerical scale, it leads to minimal bias in regression.30 Our study used large population data; the CIs remained narrow and the loss of power was minimal. Second, the lack of individual level data may have overestimated or ‘double counted’ health service use among individuals with more than one chronic disease or when individuals were admitted to hospital through the emergency department and were counted as both the emergency department and hospital admission encounters. The low proportionate rate of hospitalisation in this study was small, suggesting that this impact was minimal. Finally, in our analysis of the AQHI, we have not analysed other pollutants, such as carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide, which may be important morbidity factors in certain regions.

Future directions would do well to explore the role that comorbidities play in the relationship between exposure to air pollution and health service use. Further, it would be interesting to study the effects of air pollution on health service use among those who are revisiting the healthcare system for a disease or condition that they already have, compared to those who are being diagnosed for a new disease or condition.

Conclusion

This study suggests that air pollution exposure should be considered a risk factor for acute health morbidities among people with certain common chronic diseases. Timely AQHI air quality advisories with integrated risk reduction messages may lead to reduced morbidity associated with acute exposures to air pollution in individuals living with chronic diseases; the AQHI may also be useful in guiding public health and environmental health policy by accurately and consistently quantifying the health impacts of air pollution.

Footnotes

Contributors: TT initiated, designed the study, conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. LF prepared all tables and graphs. JS prepared data sets and descriptive statistics. JS, ASG, SD, CL and RF commented on drafts. All authors have seen and approved the final version.

Funding: Funding for this project was made available through the Best in Science Programme, provided by Ontario's Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. This study was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences had no role in study design, analysis, interpretation of data or writing of the report. The opinions, results and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences or the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change is intended or should be inferred.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.To T, Shen S, Atenafu EG et al. . The air quality health index and asthma morbidity: a population-based study. Environ Health Perspect 2013;121:46–52. 10.1289/ehp.121-a46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Air Quality Health Index. Secondary Air Quality Health Index 2012. http://www.ec.gc.ca/cas-aqhi/default.asp?lang=En&n=CB0ADB16–1

- 3.Environics Research Group Ltd. Development of a health-based air quality index for Canada—public opinion research 2004–05. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann B, Luttmann-Gibson H, Cohen A et al. . Opposing effects of particle pollution, ozone, and ambient temperature on arterial blood pressure. Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:241–6. 10.1289/ehp.1103647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko FW, Hui DS. Air Pollution and COPD. Respirology 2012;17:395–401. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavigne E, Villeneuve PJ, Cakmak S. Air pollution and emergency department visits for asthma in Windsor, Canada. Can J Public Health 2012;103:4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wellenius GA, Burger MR, Coull BA et al. . Ambient air pollution and the risk of acute ischemic stroke. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:229–34. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linares C, Diaz J. Short-term effect of PM2.5 on daily hospital admissions in Madrid (2003–2005). Int J Environ Health Res 2010;20:129–40. 10.1080/09603120903456810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vencloviene J, Grazuleviciene R, Barbaskiene R et al. . Short-term nitrogen dioxide exposure and geomagnetic activity interaction: contribution to emergency hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Int J Environ Health Res 2011;21:149–60. 10.1080/09603123.2010.515671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US EPA. Integrated Science Assessment for Oxides of Nitrogen—Health Criteria (Final Report). Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US EPA. Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter (Final Report). Washington DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US EPA. Integrated Science Assessment of Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants (Final Report). Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stieb DM, Burnett RT, Smith-Doiron M et al. . A new multipollutant, no-threshold air quality health index based on short-term associations observed in daily time-series analyses. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2008;58:435–50. 10.3155/1047-3289.58.3.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moshammer H, Hutter HP, Kundi M. Which metric of ambient ozone to predict daily mortality? Atmos Environ 2013;65:171–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frome EL. The analysis of rates using Poisson regression methods. Biometrics 1983;39:665–74. 10.2307/2531094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 9, 2006.

- 17.Prüss-Üstün A, Corvalán C. . Preventing disease through healthy environments. Towards an estimate of the environmental burden of disease. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Centre for Environment and Health. Quantification of the Health Effects of Exposure to Air Pollution, Report of a WHO Working Group. Bilthoven, the Netherlands: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook R, Franklin B, Cascio W et al. . Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2004;109:2655–71. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson D, Parker J. Air pollution exposure and self-reported cardiovascular disease. Environ Res 2009;109:582–9. 10.1016/j.envres.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearson J, Bachireddy C, Shyamprasad S et al. . Association between fine particulate matter and diabetes prevalence in the US. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2196–201. 10.2337/dc10-0698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer U, Herder C, Sugiri D et al. . Traffic-related air pollution and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the SALIA cohort study. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1273–9. 10.1289/ehp.0901689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puett RC, Hart JE, Schwartz J et al. . Are particulate matter exposures associated with risk of type 2 diabetes? Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:384–9. 10.1289/ehp.1002344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coogan PF, White LF, Jerrett M et al. . Air pollution and incidence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in black women living in Los Angeles. Circulation 2012;125:767–72. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.052753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szyszkowicz M, Rowe BH, Brook RD. Even low levels of ambient air pollutants are associated with increased emergency department visits for hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:360–6. 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowka MR, Bard RL, Rubenfire M et al. . Patient awareness of the risks for heart disease posed by air pollution. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2011;53:379–84. 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Copes R. Review of air quality index and air quality health index. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario), 2013:219. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clean Air Network. Hong Kong ranked 8th highest in the world for mortalities due to air pollution. Secondary Hong Kong ranked 8th highest in the world for mortalities due to air pollution 2012. http://www.hongkongcan.org/eng/2012/02/press-release-hong-kong-ranked-8th-highest-in-the-world-for-mortalities-due-to-air-pollution/

- 29.Government of Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department. Air Quality Health Index. Secondary Air Quality Health Index 2013. http://www.aqhi.gov.hk/en/what-is-aqhi/faqs.html

- 30.Armstrong BG. Methodology series: effect of measurement error on epidemiological studies of environmental and occupational exposures. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:651–6. 10.1136/oem.55.10.651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]