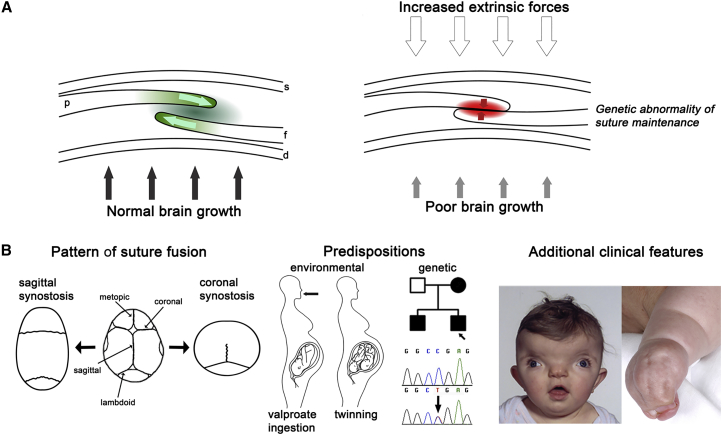

Figure 1.

Overview of Clinical Causes and Classification of Craniosynostosis

(A) Cross-section of coronal suture showing the developing parietal bone (p) overlying the frontal bone (f). Internally, the dura mater (d) separates the calvaria from the brain; skin (s) is external. Left, normal growth of the skull vault is regulated by a delicate balance of proliferation and differentiation occurring within the suture (green shading) co-ordinated with enlargement of the underlying brain (black arrows). Right, in craniosynostosis this balance has been disturbed by excessive external force on the skull, usually during pregnancy (unfilled arrows), inefficient transduction of stretch from the growing brain (gray arrows), or intrinsic abnormality of signaling within the suture itself (red shading).

(B) Approaches to clinical classification. Left: view of skull from above (front at top). Normal skull with major vault sutures identified is central. To either side, the examples show skull shapes resulting from sagittal synostosis (left) and bilateral coronal synostosis (right). Note, the metopic suture closes physiologically at the age of 3–9 months.12 Center: the clinical history can reveal possible environmental predispositions such as teratogen exposure (most commonly maternal treatment with the anticonvulsant sodium valproate13) or twinning (intrauterine constraint);14 affected relatives with craniosynostosis (filled symbols in pedigree) suggest a likely genetic cause, which can be confirmed by diagnostic genetic testing. Right: clinical examination can reveal facial dysmorphic features such as hypertelorism (wide spaced eyes) and grooved nasal tip, suggesting craniofrontonasal syndrome (left), or other physical features such as syndactyly characteristic of Apert syndrome (right). Clinical photographs reproduced, with permission, from Johnson and Wilkie9 and Twigg et al.15