Abstract

Music is considered as an universal language and has influences the human existence at various levels.In recent years music therapy has evolved as a challenge of research with a clinical approach involving science and art. Music therapy has been used for various therapeutic reasons like Alzheimer’s disease,Hypertension and mental disorders to name a few. We conducted a study to establish the effect of the classical ragam Anandhabhairavi on post operative pain relief. A randomized controlled study involving 60 patients who were to undergo surgery was conducted at PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research,Coimbatore.30 patients selected at random and were exposed to the ragam Anandhabhairavi which was played in their room pre operatively (from the day they got admitted for surgery) and 3 days post operatively. The control group did not listen to the music during their stay in the hospital. An observation chart was attached in which the requirement of analgesics by the patient was recorded. On completion of the study and on analysis,the ragam Anandhabhairavi had a significant effect in post operative pain management which was evidenced by the reduction in analgesic requirement by 50 % in those who listened to the ragam.A significant p value of <0.001 was obtained.

Keywords: Music therapy, Pain management, Post operative pain, Anandhabhairavi, Analgesic requirement

Introduction

Music is considered a universal language and has influenced the human existence at all levels. It is a medium for communication, which can be both pleasant and healing experience. It is believed that therapy using music improves the quality of a person’s life and can be aided in the physical, physiological, and emotional integration of the individual in the treatment of illness or disability.

The effects of music on humans have been well documented for thousands of years. There are several individual reactions to music that are dependent on individual preferences, moods, or emotions [1, 2]. It has been reported that music of different styles showed consistent cardiovascular and respiratory responses in most subjects, in whom responses were related to tempo and were associated with faster breathing [3, 4]. The responses were qualitatively similar in musicians and nonmusicians, and apparently were not influenced by musical preferences, although musicians did respond more.

Music expresses what cannot be spoken and what is impossible to remain silent about

—Victor Hugo (1802–1885) [5]

In recent years, music has been increasingly used as a therapeutic tool in the treatment of different diseases [6–8]. However, the physiological basis of music therapy is not well understood even in normal subjects [9]. The purpose of the present review is to summarize the different effects of music on health and the cardiovascular system.

Music, Health, and Medicine—A Topic for Everybody

It is well-known that music can evoke emotional responses that improve quality of life, but, by the same token, they can also induce stress and aggressiveness [10]. Music may enhance positive or calming emotions and has played an important role in the “making of health” throughout human history through its use in rituals and religious services. Music improves concentration but has different neurophysiological aspects, whose effectiveness is governed by individual preferences. The role of music correlates with music profiles, and continuous “mirroring” of music profiles appears to be present in all subjects, regardless of musical training, practice, or personal taste, even in the absence of accompanying emotions [11]. The ability of music to increase physical work activity has been documented for 2,800 years. In ancient Greece, the kithara (a harp-like instrument held on the lap) and flute music was played during the Olympic Games with the goal of improving sporting activities. It has been shown that this led to better athletic performances (improvement ~15 %). In addition, effect of music therapy increasingly used in different disciplines, from patients with neurological disease to intensive care and palliative medicine [12–14].

Brain and Heart—the Power of Music to Enhance Memory and Learning

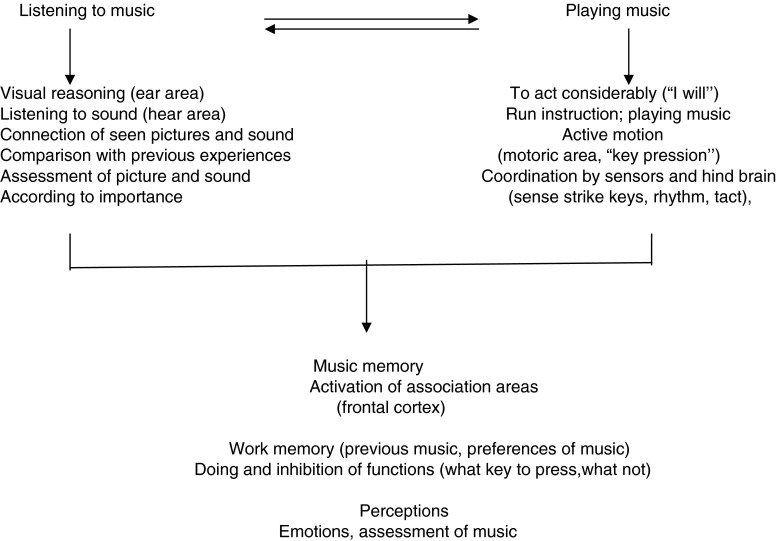

The human brain is divided into two hemispheres, and the right hemisphere has been traditionally identified as the seat of musical appreciation. However, no one has found a “musical center” there, or anywhere else. Studies of musical understanding amongst people who have damage to either hemisphere, as well as brain scans of people taken while listening to music, reveal that music perception emerges from the interplay of activity in both sides of the brain. Some brain circuits respond specifically to music; but, as you would expect, parts of these circuits participate in other forms of sound processing. For example, the region of the brain dedicated to perfect pitch is also involved in speech perception. Music and other sounds entering the ears travel to the auditory cortex, assemblages of cells just above both ears. The right side of the cortex is crucial for perceiving pitch as well as certain aspects of melody, harmony, timbre, and rhythm. The left side of the brain in most people excels at processing rapid changes in frequency and intensity, in both music and words. Both the left and right sides are necessary for complete perception of rhythm. The frontal cortex of the brain, where working memories are stored, also plays a role in rhythm and melody perception. Other areas of the brain deal with emotion and pleasure. The power of music to affect memory is quite intriguing. Mozart’s music and baroque music, with a pattern of 60 beats per minute, activate both the left and right brains. The simultaneous left and right brain action maximizes learning and retention of information. The information being studied activates the left brain, while the music activates the right brain. Also, activities which engage both sides of the brain at the same time, such as playing an instrument or singing, cause the brain to become more capable of processing information (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Brain association areas—localization of different functional areas in the left or right brain hemisphere

Fig. 2.

Processes and responses associated with listening to music, playing music, and musical memory

Review of Literature

Healing, relaxing music brings the fields of resonance around and within us back to order and sets into motion a pattern that attunes us to our natural healthy rhythm. Stress is at the cause of most human problems today. Relaxing and healing music helps the stressed out modern-day individual relieve stress.

The human body is like a musical instrument, expressing numerous frequencies and rhythms in a constantly changing spectrum of life. It responds and resonates in consonance with music, sounds, speech and thought from the environment, and undergoes changes of heart beat, breathing, blood chemistry and circulation of energy in various energy centers (Chakras) of the body.

—Pandit Roop Verma, a world renowned sitarist

Studies have suggested that music can have various benefits physically such as reducing muscle tension and chronic pain as well as psychologically helping recall past events, reinforcing reality and altering mood by relieving anxiety and depressions [15].

Studies in India

A government sponsored Raga Research Center, Claims that intense research proves that Raga Shankarabharanam aids to cure mental illness: Ananda Bhairavi has a positive effect on hypertension, Bilahari reduces stomach problems, and Bhairavi reduces back pain.

Dr. T. Mythily, a consultant cognitive neuropsychologist and a pioneer in music therapy, claims that diabetes is mainly due to stress and music is known to be a great stress buster for it.

Studies in other Countries

Some of the statistical studies by medical resonance music therapy approved by the government of Germany show that 58 % of the patients under the study who were listening to the prescribed music experienced relief from pain during minor surgery, as opposed to only 8 % in the control group. Another study showed a significant 78.6 % reduction of analgesics following gynecological surgery, which led to a considerable reduction in the quantities of the pain-killing medicines to be prescribed.

Good and his colleagues investigated the effect of relaxation, music, and the combination of relaxation and music on postoperative pain across between 2 days and two activities (ambulation and rest) and across ambulation each day [16]. This secondary analysis of a randomized-controlled trial was conducted from 1995 to 1997. Multivariate analysis indicated that although pain decreased by day 2, interventions were not different between days and activities. They were effective for pain across ambulation on each day, across ambulation and across rest over both days (all P < 0.001) and had similar effects by day and by activity.

Looscin investigated the effect of music (musical preferences of subjects) on the pain of selected postoperative patients during the first 48 h [17]. The subjects were 24 female gynecologic and/or obstetric patients who made the control and experimental sample, paired accordingly by age, type of surgery, educational background, and previous operative experience. The measurement of the experimental variable was done using an overt pain reaction rating scale (OPRRS) devised by the author. Analgesics received, arterial blood pressures, pulse rates, and respiratory rates were also used to test the hypothesis. Significant differences were found between the groups of postoperative patients in their musculoskeletal and verbal pain reactions during the first 58 h at 0.05 level.

Standley has consistently reviewed the literature relating to music therapy applications in medical settings and made a meta-analysis of the current findings from 55 studies utilizing 129 dependent variables [18, 19]. Standley concludes that the average therapeutic effect of music in medical treatment is almost one standard deviation greater than without music.

Prinsley recommends music therapy for geriatric care because it reduces the individual prescription of tranquilizing medication, reduces the use of hypnotics in the hospital ward, and helps overall rehabilitation [20].

Bonny has suggested a series of musical selections for tape recordings, which can be chosen for their sedative effects, according to other mood criteria, associative imagery, and relaxation potential; none of which have been empirically confirmed [21]. However Updike, in an observational study, confirms Bonny’s impression that there is a decreased systolic blood pressure and a beneficial mood change from anxiety to relaxed and calm mood when sedative music is played [22].

Bolwerk set out to relieve the state anxiety of patients in a myocardial infarction ward using recorded classical music [23]. Forty adults were randomly assigned into two equal groups: one group listened to relaxing music during the first 4 days of hospitalization, and the other received no music. There was a significant reduction in state anxiety in the treatment group.

In the supportive care program of pain service to the neurology department of Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, a music therapist is part of that supportive team along with a psychiatrist, nurse clinician, neuro-oncologist, chaplain, and social worker [24]. Music therapy is used to promote relaxation, to reduce anxiety, to supplement other pain control methods, and to enhance communication between the patient and the family [25, 26].

Aldridge in a single case study emphasizes the benefits of expression facilitated by playing music for the postoperative care of a woman after mastectomy [27].

Gustorff has successfully applied creative music therapy in coma patients who were otherwise unresponsive [28, 29]. Matching her singing with the breathing patterns of the patient, she has stimulated changes in consciousness which are both measurable on a coma rating scale and apparent to the eyes of the clinician.

Music and Cardiovascular Diseases

Recently, several studies have analyzed the effect of music during cardiac catheterization, prior to and after cardiac surgery and during rehabilitation. In addition, there are some reports that studied the effect of music in intensive care medicine, in geriatrics, and in patients with neurological diseases or depressive syndromes. It is essential to note that studies have shown that music has beneficial effects on different physiological parameters and will become an important option when treating these patients.

Effect of Music on the Cardiovascular System

It has been shown that the structure of a piece of music has a constant dynamic influence on cardiovascular and respiratory responses, which correlate with musical profiles.

It was pointed out that the cardiovascular (particularly skin vasomotion) and respiratory fluctuations mirrored the musical profile, thus highlighting its importance in relation to the therapeutic use of music. Specific musical phrases (frequently at a rhythm of 6 cycles/min in famous arias by Verdi) can synchronize inherent cardiovascular rhythms, thus modulating cardiovascular control. This occurred regardless of respiratory modulation, which suggests the possibility of direct entrainment of such rhythm which led to the speculation that some of the psychological and somatic effects at music could be mediated by modulation or entrainment of these rhythms [16]. Music as therapy is an option for all since it has been reported that musicians and nonmusicians alike showed similar qualitative responses (cardiovascular and respiratory system). This suggests that “active” playing of music is not essential to induce synchronization with music [1]. However, it was pointed out that musicians appeared to show higher cardiovascular and respiratory modulation induced by music. They also tended to respond more than nonmusicians to more “intellectual” music such as that of Bach or Mozart [1, 15]. If music induces similar physiological effects in musicians and nonmusicians, standard “music therapeutic” interventions would be possible. Therefore, it seems necessary to identify effects of music under different conditions [5, 6]. Is the music written by Bach or Mozart helpful for everybody? Is classical music better than heavy metal or techno? What music has beneficial effects in intensive care medicine and in patients with cardiovascular diseases? Are responses to rhythmic phrases different from the effect of silence?

Aim and Objectives

The above-mentioned studies show that music does have a role in the well-being of a patient in terms of reduction of anxiety, stress, and pain, control of blood pressure, and improvement of social well-being. Previous studies have shown that the raga Ananda Bhairavi in Carnatic music has a significant role in reduction of blood pressure.

The aim of our study is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the raga Ananda Bhairavi in postoperative pain relief management.

Objectives

To study the nonrequirement or the reduction in requirement of analgesics in patients subjected to the raga Ananda Bhairavi

To compare the requirement of analgesics with a group of patients not subjected to raga Ananda Bhairavi (control)

Materials and Methods

Study design—a randomized controlled study

Study site—P.S.G. Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore

Duration of the study—September 10, 2006, to November 10, 2006

Choice of subjects and control

Surgeries included in the study

Hernia surgeries

Appendicectomy

Thyroidectomy

Breast surgeries (excluding mastectomy)

Sixty patients who were to undergo a surgery were chosen to be part of the study. A written consent was obtained from each of them.

The control group comprising of 30 patients, chosen at random, did not experience listening to the raga Ananda Bhairavi. The study group comprising of the other 30 was exposed to the raga Ananda Bhairavi, which was played in their ward preoperatively (from the time they got admitted) and 3 days postoperatively—the recorded audio CD had 12 compositions on the raga Ananda Bhairavi by different composers both vocal and instrumental.

The patients were given a questionnaire, which had the following two parts:

to be filled preoperatively, before the patient started listening to raga Ananda Bhairavi

to be filled postoperatively, 3 days after listening to the music

Record of Analgesic Requirement

An observation chart was attached to the questionnaire in which the requirement of analgesics by the patient was recorded.

Statistical Analysis

A student’s t-test (SEDM-standard error of difference in means) was used to find out whether the difference in the analgesic requirement of the control and study groups was statistically significant. Statistical probability of P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

The age and sex distribution of the sample and the influence of prior exposure to Carnatic music among the study group was also determined from the information obtained from the questionnaire.

Observation and Results (Tables 1, 2 and 3)

Table 1.

Requirement of analgesics by the study and control patients

| S. No. | Doses of analgesic required | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Study | |

| 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 5 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 5 | 1 |

| 7 | 5 | 2 |

| 8 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 10 | 5 | 3 |

| 11 | 5 | 2 |

| 12 | 4 | 2 |

| 13 | 6 | 1 |

| 14 | 4 | 1 |

| 15 | 6 | 1 |

| 16 | 6 | 2 |

| 17 | 4 | 3 |

| 18 | 4 | 3 |

| 19 | 6 | 1 |

| 20 | 5 | 3 |

| 21 | 4 | 1 |

| 22 | 2 | 2 |

| 23 | 4 | 3 |

| 24 | 4 | 3 |

| 25 | 3 | 1 |

| 26 | 2 | 1 |

| 27 | 2 | 1 |

| 28 | 3 | 2 |

| 29 | 5 | 2 |

| 30 | 3 | 2 |

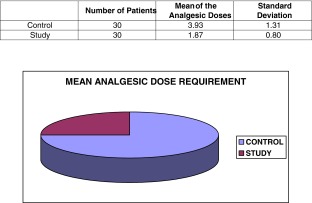

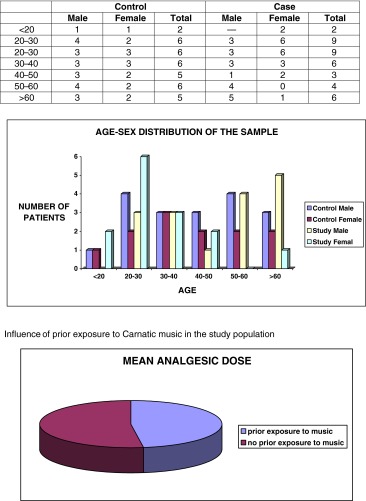

Table 2.

Mean analgesic dose requirement

Table 3.

The age and sex distribution of the sample

Interpretation

Difference in means of the requirement of analgesics of the study and control groups—null hypothesis was considered. The t value was calculated using SEDM and found to be 7.36. Comparing this with the table values, we find 7.36 ≫ 3.46 (DF = 58, at the level of P = 0.001). Therefore, null hypothesis is rejected. The difference in means between the two groups is statistically significant with P < 0.001.

Influence of the prior exposure to Carnatic music among the study population—the influence of previous exposure to Carnatic music was studied among the study population. A similar ‘t’ test was performed and found that the difference was not significant with P > 0.05.

Discussion

Music is a combination of frequency, beat, density, tone, rhythm, repetition, loudness, and lyrics. Different basic personalities tend to be attracted to certain styles of music. Music influences our emotions because it takes the place of and extends our languages. Research conducted over the past 10 years has demonstrated that persistent negative emotional experiences or an obsession and preoccupation with negative emotional states can increase one’s likelihood of acquiring the common cold, other viral infections, yeast infestations, hypersensitivities, heart attacks, high blood pressure, and other disease. For better personal health, we can then choose “healthful” music and learn to let ourselves benefit from it. The most benefit from music in terms of health is seen for classical and mediation music, whereas heavy metal or techno are ineffective or even dangerous. There are many composers that effectively improve quality of life and health, particularly Bach, Mozart, and Italian composers. Various studies have suggested that this music not only makes one happy, but also significantly affects the cardiovascular system and significantly influences heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood pressure. Music is effective under different conditions and can be utilized as an effective intervention in patients with cardiovascular disturbances, pain, depressive syndromes, and psychiatric diseases and in intensive care medicine. Therefore, music plays an important role in people’s lives and, by extension, an important role in medicine.

Music therapy is a well-established health service offered in many hospitals in other countries. In India it has emerged in the recent years, and is still a developing health service. Carnatic music is a known therapeutic in many disease states such as diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension. The raga Ananda Bhairavi has been proved to have a role in reduction of blood pressure. Still, it remains a minimally studied area. This study was carried out to provide a thrust to the Carnatic music therapy and provide evidence-based results that the raga Ananda Bhairavi also has a role in pain relief, which is clear from the reduction of analgesic requirement by 50 % in those who listened to raga Ananda Bhairavi.

Conclusion

The raga Ananda Bhairavi has an effect in postoperative pain management which is evidenced by the reduction in analgesic requirement by 50 % in those who listened to raga it postoperatively 3 days. A significant P value of <0.001 was obtained.

The prior exposure to Carnatic music among the study population has no effect on the reduction in the requirement of analgesics.

References

- 1.Panksepp J, Bernatzky G. Emotional sounds and the brain: the neuroaffective foundations of musical appreciation. Behav Process. 2002;60:133–155. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(02)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krout RE. Music therapy with imminently dying hospice patients and their families: facilitating release near the time of death. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:129–134. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mramor KM. Music therapy with persons who are indigent and terminally ill. J Palliat Care. 2001;17:182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norton A, Zipses L, Marchina S, et al. Melodic intonation therapy: shared insights on how it is done and why it might help. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1169:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernardi L, Porta C, Casucci G, et al. Dynamic interactions between musical, cardiovascular, and cerebral rhythms in humans. Circulation. 2009;30:3171–3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.806174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grewe O, Nagel F, Kopiez R, et al. How does music arouse “chills”? Investigating strong emotions, combining psychological, physiological, and psychacoustical methods. Ann Acad Sci. 2005;1060:446–449. doi: 10.1196/annals.1360.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yashie M, Kudo K, Murakoshi T, et al. Music performance anxiety in skilled pianists: effects of social-evaulative performance situation on subjective, autonomic, and electromyographic reactions. Exp Brain Res. 2009;199:177–126. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakahara H, Furuya S, Obata S, et al. Emotion-related changes in heart rate and its variability during performance and perception of music. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1169:359–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E, et al. Effect of music on depression levels and physiological responses in community-based older adults. Int J Health Nurs. 2009;18:285–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koelsch S. A neuroscientific perspective on music therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1169:374–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storm F. Die Heilkraft bestimmter Musiksite. In: Storm F, editor. Heilen mit Tönen. Stuttgart: Lüchow-edition; 2006. pp. 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Argstatter H, Haberbosch W, Bolay HV. Study of the effectiveness of musical stimulation during intracardiac catheterization. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95:14–22. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goertz W. Bach order jazz-vom Patienten oder vom Los ewählt? Zur Wirkung von Musik im Herkatheterlabor. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;86:802. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bringman H, Giesecke K, Thörne A, et al. Relaxing music as pre-medication before surgery: a randomized controlled trail. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:759–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavin M (1991) The lost chord: Reaching the person with dementia through the power of music Mt. Airy, MD: Eldersong. Gaynor, M. (1999). Sounds of Healing. NY: Broadway Books Lane, D. (1994). Music as Medicine. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- 16.Good M, Stanton-Hicks M, Grass JA, Anderson GC, Lai H-L, Roykulcharoen V, Adler PA. Relaxation and music to reduce post surgical pain. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(2):208–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loscin RG. The effect of music on pain of selected post operative patients. J Adv Nurs. 1981;6(1):19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1981.tb03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Standley J. Music as a therapeutic intervention in medical and dental settings. In: Wigram T, Saperston B, West R, editors. Art and science of music therapy. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Standley JM. Music research in medical/dental treatment: meta analysis and clinical applications. J Music Ther. 1986;23(2):56–122. doi: 10.1093/jmt/23.2.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prinsley D. Music therapy in geriatric care. Aust Nurs J. 1986;15(9):48–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonny H, McCarron N (1984) Music as an adjunct to anaesthesia in operative procedures. J Am Assoc Nurse Anesth 55–57

- 22.Updike P. Music therapy results for ICU patients. Dimens Crit Care Nurse. 1990;9(1):39–45. doi: 10.1097/00003465-199001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolwerk CA. Effects of relaxing music on state anxiety in myocardial infarction patients. Crit Care Nurse. 1990;13(2):63–72. doi: 10.1097/00002727-199009000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coyle N. A model of continuity of care for cancer patients with chronic pain. Med Clin North Am. 1987;71(2):259–270. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey LM. The effects of live music versus tape-recorded music on hospitalized cancer patients. Music Ther. 1983;3(1):17–28. doi: 10.1093/mt/3.1.17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey LM. The use of songs with cancer patients and their families. Music Ther. 1984;1(4):5–17. doi: 10.1093/mt/4.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aldridge G. “A walk through Paris”: the development of melodic expression in music therapy with a breast-cancer patient. Arts Psychother. 1996;23:207–223. doi: 10.1016/0197-4556(96)00024-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aldridge D, Gustorff D, Hannich H-J. Where am I? Music therapy applied to coma patients. J R Soc Med. 1990;83(6):345–346. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldridge D. Music therapy in dementia care. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]