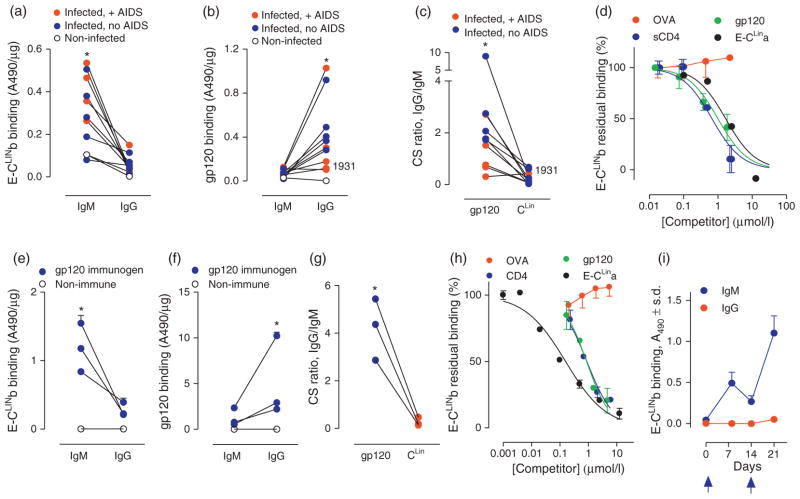

Fig. 1. CLIN-selective deficient IgG but not IgM synthesis in HIV-infected humans (panels a–d) and mice immunized with gp120 (panels e–i).

(a) E-CLINb binding by serum IgM and IgG (n = 10 HIV-infected humans; 5 without AIDS, 5 with AIDS). Connecting lines identify individual patients. IgG from all infected patients displayed lower E-CLINb binding than the IgM (*P range <0.0001–0.03 for individual infected patients; P <0.0001 for pooled values; P <0.02 for pooled ‘no AIDS’ values; P <0.01 for pooled ‘+ AIDS’ values). Binding activities of IgM and IgG from pooled serum of noninfected humans are included. The IgM binding activity in noninfected humans represents a specific CLIN recognition reaction [10]. (b) Full-length gp120 binding by the same IgM and IgG samples from the patients in panel a. As IgM binding was consistently low, several IgM data points are superimposed. gp120 was bound by IgG at superior levels compared to IgM from all infected patients except patient 1931 with AIDS (*P range <0.0001–0.02 for 9 individual infected patients; P <0.01 for pooled values without exclusion of patient 1931). (c) CS ratios for binding to full-length gp120 and CLIN antigens computed from panels a and b. The CLIN CS ratio was lower than the gp120 CS ratio for all infected patients, but patient 1931, indicating a CLIN-selective IgG deficiency (*P range <0.0001–0.007 for 9 individual infected patients; P <0.0001 for pooled values without exclusion of patient 1931). (d) Specific IgM–CLIN binding. Competition curves showing residual E-CLINb binding by IgM from infected patient 1932 in the presence of increasing concentration of sCD4, gp120, E-CLINa or control ovalbumin (OVA). Binding in diluent without a competitor was 0.53 ± 0.03 A490 units (100% value). (e) E-CLINb binding by serum IgM and IgG from mice immunized with gp120. Each closed symbol represents pooled IgM or IgG binding activity from an independent immunization study (study 1a, 2a, 3a in Table S2; n = 4–10 mice/immunization). Connecting lines identify individual immunization studies. IgM and IgG from pooled serum of 10 nonimmunized mice displayed negligible binding. IgG from gp120-immunized mice consistently displayed lower E-CLINb binding than the IgM (*P <0.004, 0.002 and 0.01 for studies 1a, 2a and 3a, respectively). Binding in all mouse antibody studies was tested in the presence of excess E-hapten 1 (100 μmol/l; panels e–i). (f) Full-length gp120 binding by the same IgM and IgG samples shown in panel a. IgG from the gp120-immunized mice consistently displayed greater gp120 binding than the IgM (*P <0.01, 0.002 and 0.01 for studies 1a, 2a and 3a, respectively). (g) CS ratios for binding to full-length gp120 and E-CLINb antigens computed from panels e and f. The CLIN CS ratio was consistently lower than the gp120 CS ratio (P <0.005, 0.002 and 0.02 for studies 1a, 2a and 3a, respectively). (h) Specific IgM–CLIN binding. Competition curves showing residual E-CLINb binding by IgM from a study 2a mouse immunized with gp120 in the presence of increasing concentrations of sCD4, gp120, E-CLINa or control OVA. Binding in diluent without a competitor was 0.86 ± 0.01 A490 units (100% value). (i) Memory CLIN-directed IgM response. The booster gp120 administration induced an anamnestic E-CLINb binding IgM response (1: 500 pooled serum from study 4 mice). Arrows, gp120 administrations.