Abstract

A new tandem cross enyne metathesis (CEYM)–intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction (IMDAR) has been carried out. It involves conjugated ketones, esters or amides bearing a remote olefin and aromatic alkynes as the starting materials. The overall process enables the preparation of a small family of linear bicyclic scaffolds in a very simple manner with moderate to good levels of diastereoselectivity. This methodology constitutes one of the few examples that employ olefins differently than ethylene in tandem CEYM–IMDAR protocols.

Keywords: bicyclic frameworks, cross enyne metathesis, Diels–Alder reaction, tandem reaction

Introduction

Among all metathetic processes, the enyne metathesis reaction has received significant attention as an attractive and frequently used synthetic tool in organic synthesis [1–7]. It is an atom economical process that combines alkene and alkyne moieties to generate conjugated 1,3-dienes under mild conditions. These 1,3-dienes are versatile building blocks suitable for further non-metathetic transformations, either in a step-wise or a tandem fashion. Thus, the enyne metathesis methodology has become a powerful tool for the generation of carbon–carbon bonds, expanding the utility of metathesis processes beyond olefinic substrates [8–9].

The inherent tandem nature of enyne metathesis is particularly appealing in its combination with the Diels–Alder reaction. This tandem protocol is well suited for addressing a broad range of complex molecules since multiple carbon–carbon bonds can be generated in a single operation, therefore increasing molecular complexity in a quite simple manner [10].

While examples of ring-closing enyne metathesis (RCEYM) reactions are widespread in the literature [11], the development of the intermolecular version, i.e., the cross enyne metathesis (CEYM), lagged behind probably due to difficulties in controlling the stereoselectivity in the newly formed double bond leading to the formation of mixtures of E and Z-isomers. These inherent selectivity problems are absent when the olefin counterpart is the ethylene unit, which explains why most of the reported examples that combine a CEYM reaction with a Diels–Alder cycloaddition in a tandem manner involve the use of ethylene as the olefin partner either by employing an internal source of it or by bubbling it into the reaction mixture. This strategy allowed for the synthesis of a wide variety of natural and non-natural products in the last decade [12–22].

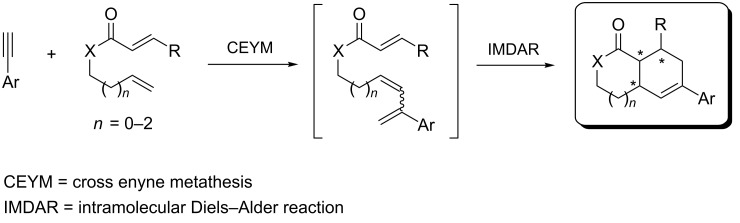

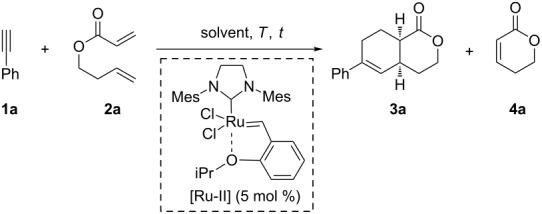

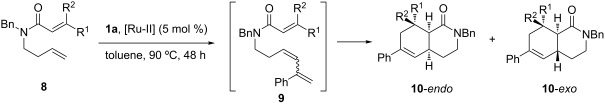

The use of olefins other than ethylene in CEYM-Diels–Alder tandem protocols is very scarce. The first example was reported in 2005 by combining Baylis–Hillman adducts with alkynes in the presence of second generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst [23]. After the initial formation of the trienic unit, an intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction (IMDAR) rendered highly functionalized bicyclic derivatives in a very efficient manner. More recently, a multicomponent CEYM–intermolecular hetero-Diels–Alder reaction involving alkynes, ethyl glyoxalate and ethyl vinyl ether was described for the preparation of 2,3-dihydropyrans [24–25]. Additionally, a tandem CEYM–IMDAR reaction in combination with a final aromatization step was employed for the synthesis of biaryl derivatives [26]. Herein, a new example of this tandem protocol CEYM–IMDAR with alkynes and α,ω-dienes as starting materials is reported, which will give access to a new family of linear bicyclic carbo- and heterocyclic scaffolds. We envisioned that the initial CEYM would occur in the electronically neutral olefin to generate the corresponding triene intermediate, which would evolve under the reaction conditions through the cycloaddition event to render the final products (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Tandem cross enyne metathesis–intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction.

Results and Discussion

The use of 1,5-, 1,6- and 1,7-dienes in cross metathesis-type transformations is not trivial since chemoselectivity issues can arise. It is well known that electronically deficient olefins should undergo metathesis in a slow rate based on the model developed by Grubbs and coworkers that classifies olefins and predicts their reactivity in CM reactions [27]. We anticipated that, according to these studies, in substrates bearing two different olefin units one being an α,β-unsaturated moiety, the tandem CM–IMDAR protocol would initiate on the electronically neutral olefin. Furthermore, those dienes could undergo an intramolecular cyclization (RCM) promoted by the ruthenium carbene that would compete with the desired intermolecular CM process.

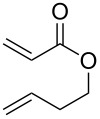

In order to prove our assumptions, phenylacetylene (1a) and conjugated ester 2a were employed as model substrates to study the tandem protocol. The results obtained in the optimization process are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Optimization of the tandem CEYM–IMDAR.

| ||||||

| entry | solvent | T (°C) | 1a:2a | t (h) | additive | % yield 3aa |

| 1 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 6 | – | 25 |

| 2 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 24 | – | 37 |

| 3 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 48 | – | 57 |

| 4 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 72 | – | 39 |

| 5 | toluene | 90 | 1:1 | 48 | – | 36 |

| 6 | toluene | 90 | 1:5 | 48 | – | 30 |

| 7 | toluene | 110 | 1:3 | 48 | – | 52 |

| 8 | toluene | 140 | 1:3 | 48 | – | 37 |

| 9 | DCM | 60 | 1:3 | 48 | – | 25 |

| 10 | C6H5CF3 | 90 | 1:3 | 48 | – | 60 |

| 11 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 48 | Ti(OiPr)4b | 38 |

| 12 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 48 | BF3·OEt2b | 15 |

| 13 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 48 | thioureac | 49 |

| 14 | toluene | 90 | 1:3 | 48 | BQb,d | 37 |

aIsolated yield after column chromatography. Variable amounts of 4a were observed in all cases, but never exceeded 15% (based on 2a). Some unreacted 2a was also detected in all cases; b5 mol %; c1 mol %; dbenzoquinone.

The first attempt to carry out the projected tandem protocol was performed by heating 1.0 equiv of phenylacetylene (1a) and 3.0 equiv of diolefinic ester 2a in toluene in the presence of second generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst [Ru-II]. After 6 hours at 90 °C, bicyclic lactone 3a was obtained in 25% yield (Table 1, entry 1), together with lactone 4a (15%, arising from the ring closing metathesis (RCM) of 2a), and unreacted 2a. The isolated yield of 3a was improved to 57% by increasing the reaction time to 48 hours (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). An extended reaction time (72 h) led to a drop in the final yield (Table 1, entry 4). In all cases variable amounts of 4a, which never exceeded 15%, and unreacted 2a were detected in the crude mixture. On the other hand, it is worth noting that although compound 4a can be considered as a good dienophile, its intermolecular Diels–Alder reaction with the triene intermediate formed after the initial CEYM was not observed. This fact, together with the successful formation of the desired bicycle 3a, indicates that the CEYM between 1a and 2a is faster than the RCM of 2a, and also that the intramolecular Diels–Alder process is more favoured once the triene unit is formed.

Different ratios of substrates 1a:2a did not improve the efficiency of the process (Table 1, entries 5 and 6). Likewise, higher temperatures afforded comparable yields of product 3a (Table 1, entries 7 and 8). When the reaction was performed in DCM only 25% of 3a were isolated, while the use of trifluorotoluene as solvent afforded the best yield (60%) of the tandem process (Table 1, entries 9 and 10).

The use of Lewis acids as co-catalysts was also tested although the efficiency of the process did not improve neither with Ti(OiPr)4 nor with BF3·OEt2 (Table 1, entries 11 and 12). Alternatively, thiourea derivatives have proven to be very effective hydrogen-bonding catalysts for Diels–Alder reactions [28]. However, in our case no influence was observed when the reaction was performed in the presence of diaryl thioureas (Table 1, entry 13). Finally, the use of benzoquinone (BQ) as an additive, which has been reported to suppress the formation of byproducts in enyne metathesis protocols [29], was also unsuccessful in the present case (Table 1, entry 14).

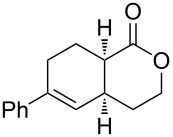

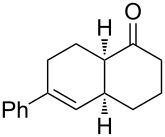

It is noteworthy that compound 3a was always obtained as a single diastereoisomer showing a cis fusion between the two cycles [30].

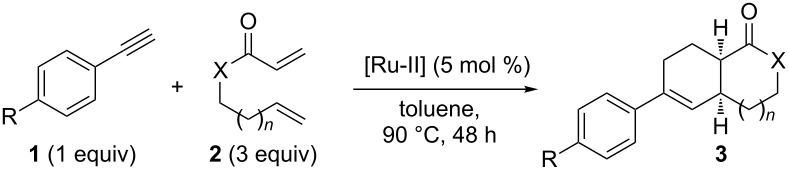

Next, the optimized conditions (heating at 90 °C for 48 h in the presence of Ru-II catalyst) were applied to other aromatic alkynes 1 and dienes 2, affording a new family of linear carbocycles and heterocycles 3 in moderate yields (Table 2).

Table 2.

Scope of the tandem CEYM-IMDAR protocol.

| |||

| entry | 1 (R) | 2 | 3 (yield)a |

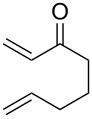

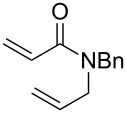

| 1 | 1a (H) |

2a |

3a (57%) |

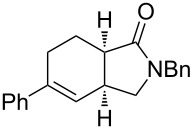

| 2 | 1a (H) |

2b |

3b (38%) |

| 3 | 1a (H) |

2c |

3c (62%) |

| 4 | 1b (F) |

2c |

3d (45%) |

| 5 | 1c (OMe) |

2c |

3e (35%) |

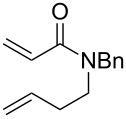

| 6 | 1a (H) |

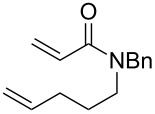

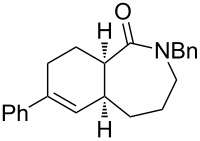

2d |

3f (50%) |

| 7 | 1a (H) |

2e |

3g (44%) |

aIsolated yields after column chromatography. All final products 3 were obtained as single diastereoisomers.

Bicyclic lactone 3a, ketone 3b and lactam 3c were obtained in moderate yields following the tandem CEYM-IMDAR protocol (Table 2, entries 1–3). Comparable yields were obtained with either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents in the starting alkyne 1 (Table 2, entries 4 and 5). In addition, 5- and 7-membered bicyclic lactams 3f and 3g were also synthesized in moderate yields (Table 2, entries 6 and 7). Again, all bicycles 3 were obtained as single diastereoisomers, assuming the same cis-stereochemistry as in compound 3a [30].

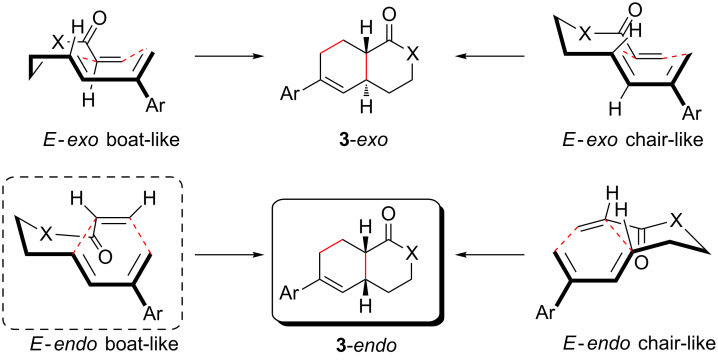

Although it was not possible to isolate the intermediate trienes formed after the initial CEYM under the reaction conditions, they should be formed as a mixture of E/Z diastereoisomers. We would expect that only the E-isomer possesses the adequate disposition to undergo the IMDAR, while the Z-isomer would not cyclize. However, since this Z-isomer was not detected after 48 h, it was assumed that this triene intermediate decomposes under the reaction conditions or, alternatively, it undergoes an RCM to render compounds 4 (Table 1) and only the final products arising from the E-isomer were observed. Moreover, the IMDAR of dienes and dienophiles linked by ester or amide tethers was theoretically studied [31]. These studies indicated that endo geometries are favoured over exo ones and also that boat-like conformations are preferred over chair-like ones. These studies accurately correlated with the experimental results observed in these types of cyclizations [32–34]. The preference of the boat-like transition state was ascribed to the co-planarity of the carbonyl group during the cycloaddition, being maximized in the E-endo boat-like transition state leading to the formation of the cis-cycloadduct 3-endo (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Stereochemical outcome of the IMDAR.

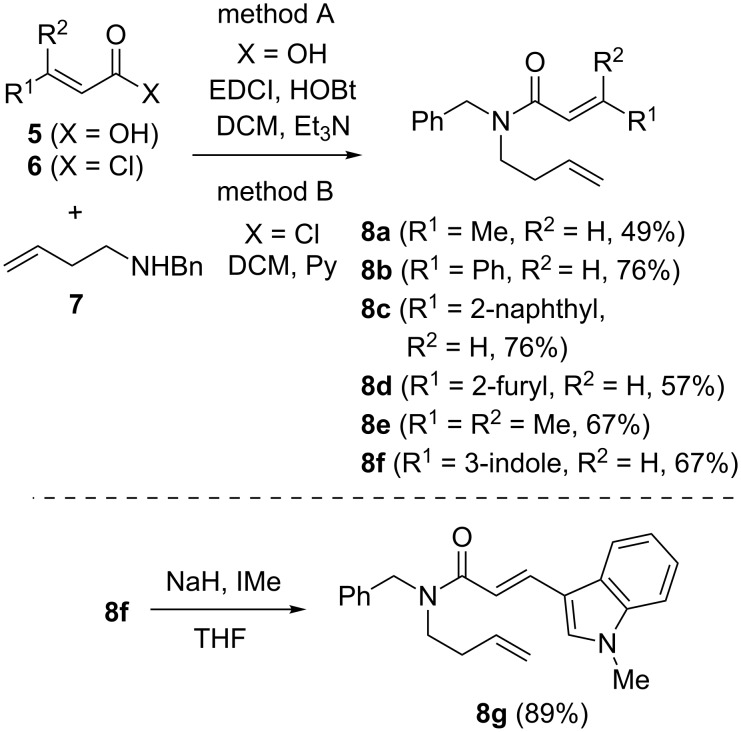

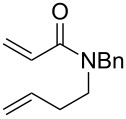

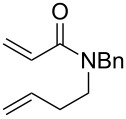

The tandem protocol was next extended to substituted dienes 8. These substrates were assembled by condensation of homoallyl benzylamine 7 with carboxylic acids 5 (method A) or acyl chlorides 6 (method B) under standard conditions (Scheme 3). Since the basic indole nitrogen in substrate 8f could interfere with the ruthenium catalyst, it was N-methylated to render compound 8g.

Scheme 3.

Preparation of starting materials 8.

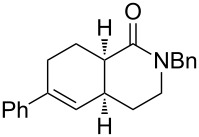

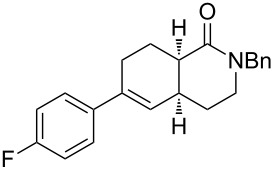

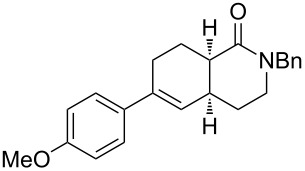

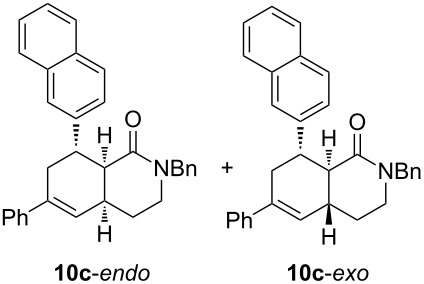

With substrates 8 in hand, they were subjected to the optimized conditions of the tandem CEYM–IMDAR protocol. The results of these tandem reactions are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Extending the scope of the tandem CEYM–IMDAR protocol to amides 8.

| ||||

| entry | 8 | 9 | 10 | % yield 10a (endo: exo)b |

| 1 | 8a | –c |  |

85 (93:7) |

| 2 | 8b |  |

|

78 (53:47) |

| 3 | 8c | –c |  |

47 (66:34) |

| 4 | 8d | –c |  |

68 (72:28) |

| 5 | 8e | –c |  |

25 (77:23) |

| 6 | 8g | –c |  |

33 (50:50) |

aIsolated yields after column chromatography; bdiasteroisomeric ratio determined by 1H NMR; cnot observed;

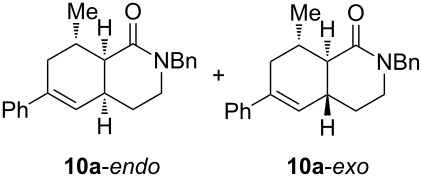

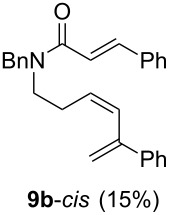

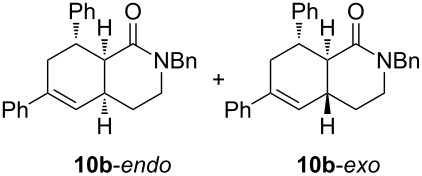

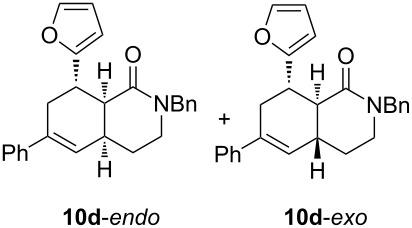

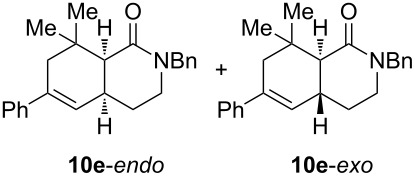

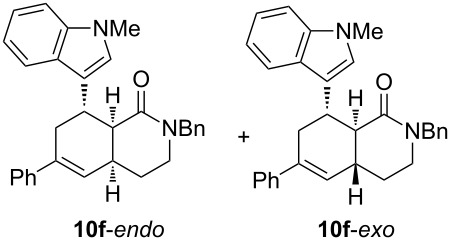

Diolefinic substrate 8a underwent the tandem sequence in excellent yield (85%) to afford the endo isomer 10a-endo as the major product together with a small amount of the exo isomer 10a-exo (Table 3, entry 1). On the other hand, compound 8b bearing a phenyl substituent at the α-olefinic carbon gave an almost equimolecular but separable mixture of bicycles 10b-endo and 10b-exo (78% overall yield). In this case, a small amount of triene intermediate 9b-cis (15% yield) was also isolated, which was in agreement with our previous assumption that the cis-triene does not undergo the IMDAR.

Diolefinic amides 8c and 8d bearing the 2-naphthyl and 2-furyl substituents, respectively, rendered the corresponding bicyclic products 10c and 10d in acceptable yields (47 and 68%) and moderate diastereoselectivity (Table 3, entries 3 and 4). The use of a trisubstituted olefin as the starting material (8e) caused a significant drop of the final yield, probably due to steric reasons (Table 3, entry 5). Finally, the indole-containing derivative 8g gave an equimolecular but separable mixture of adducts 10f-endo and 10f-exo in moderate yield (Table 3, entry 6).

It can be assumed that in these cases, the E-exo boat-like transition state is also in operation (see Scheme 2), which gives rise to the diastereoisomeric endo/exo mixtures.

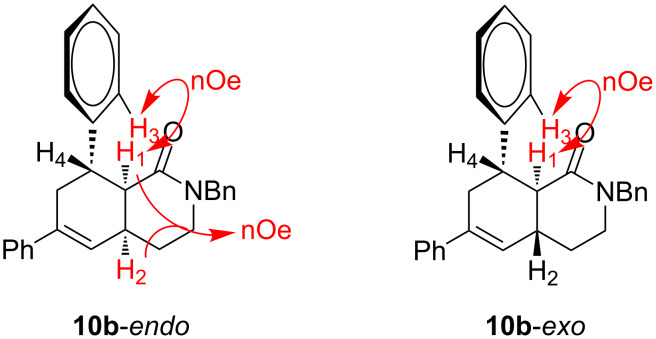

The relative stereochemistry of the final products 10 was determined on compounds 10b-endo and 10b-exo. After chromatographic separation, NOESY experiments indicated that 10b-endo shows two nOe correlations: one between H1 and H2 (which indicates the cis-fusion of the two cycles) and another one between H1 and the aromatic proton H3. These two nOe interactions, together with the absence of a correlation between H1 and H4 indicated that the phenyl ring and H1 display a cis relationship. Additionally, compound 10b-exo only showed an nOe correlation between H1 and H3 (Figure 1). For the rest of compounds 10, an analogous stereochemical outcome was assumed.

Figure 1.

Determination of the relative stereochemistry on compounds 10b.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a new tandem CEYM–IMDAR involving aromatic alkynes and dienes bearing two electronically different olefin moieties is described. Non-substituted substrates 2 are good partners in the tandem protocol affording linear bicyclic derivatives 3 as single diastereoisomers. The IMDAR takes place with complete endo selectivity, by means of an endo boat-like transition state. The use of substrates 8 with increased substitution at the β-olefinic carbon provides the formation of final products 10 as mixtures of endo/exo diastereoisomers, indicating that an exo boat-like transition state is also in operation in this case. It is noteworthy that this is one of the few examples of this tandem protocol that employs olefins other than ethylene.

Experimental

General procedure for the tandem protocol. A solution of Hoveyda–Grubbs 2nd generation (5 mol %), diene 2 or 8 (3.0 equiv) and alkyne 1 (0.5 mmol) in dry toluene 0.05 M was heated at 90 °C in a sealed tube. The reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature for 48 h. The solvents were then removed under reduced pressure and the crude mixture was purified by flash chromatography in n-hexanes/ethyl acetate.

(4aR*,8aS*)-6-Phenyl-3,4,4a,7,8,8a-hexahydro-1H-isochromen-1-one (3a). Following the general procedure described above, 3a was obtained in 57% yield as a brown oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 1.68–1.87 (m, 2H), 2.00–2.10 (m, 1H), 2.25–2.36 (m, 2H), 2.41–2.53 (m, 1H), 2.75–2.85 (m, 2H), 4.22 (dd, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 5.81–5.83 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.29 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75.5 MHz) δ 24.1, 24.7, 28.5, 32.5, 38.9, 67.3, 124.8, 125.1, 127.3, 128.3, 139.4, 141.2, 173.4; HRMS (ES): [M + 1]+ calcd for C15H17O2, 229.1223; found, 229.1233.

Supporting Information

Experimental and analytical data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (CTQ-2013-43310-P) and Generalitat Valenciana (GV/PrometeoII/2014/073) for their financial support. J. M., F. R. and A. S. thank the University of Valencia and the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad for a predoctoral fellowship.

This article is part of the Thematic Series "Progress in metathesis chemistry II".

Contributor Information

Carlos del Pozo, Email: carlos.pozo@uv.es.

Santos Fustero, Email: santos.fustero@uv.es.

References

- 1.Fischmeister C, Bruneau C. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2011;7:156. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolan S P, Clavier H. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:3305. doi: 10.1039/b912410c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Lee D. In: Handbook of Metathesis. 2nd ed. Grubbs R H, O'Leary D J, editors. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2015. p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diver S T, Clark J R. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. 2nd ed. Vol. 5. Elsevier; 2014. p. 1302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diver S T. Science of Synthesis. Vol. 46. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2009. Synthesis by Alkene Metathesis; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori M. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:121. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200600484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen E C, Lee D. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:509. doi: 10.1021/ar050024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotha S, Meshram M, Tiwari A. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2065. doi: 10.1039/b810094m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fustero S, Simón-Fuentes A, Barrio P, Haufe G. Chem Rev. 2015;115:871. doi: 10.1021/cr500182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grubbs R H. Handbook of Metathesis. 1–3. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag Gmbh and Co. KGaA; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Lee D. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:4269. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201100438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kueh J T B, Moodie L W K, Lukas N T, Larsen D S. Eur J Org Chem. 2015:1485. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201403482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fustero S, Bello P, Miró J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Haufe G, del Pozo C. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2013;9:2688. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fustero S, Bello P, Miró J, Simón A, del Pozo C. Chem – Eur J. 2012;18:10991. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotha S, Waghule G T. J Org Chem. 2012;77:6314. doi: 10.1021/jo300766f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotha S, Goyal D, Thota N, Srinivas V. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:1843. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201101744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danz M, Hilt G. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:303. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subrahmanyam A V, Palanichamy K, Kaliappan K P. Chem – Eur J. 2010;16:8545. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nandurdikar R S, Subrahmanyam A V, Kaliappan K P. Eur J Org Chem. 2010:2788. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201000001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotha S, Khedkar P. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:730. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200800924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotha S, Mandal K, Banerjee S, Mobin S M. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:1244. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200600970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaliappan K P, Subrahmanyam V. Org Lett. 2007;9:1121. doi: 10.1021/ol0701159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mix S, Blechert S. Org Lett. 2005;7:2015. doi: 10.1021/ol050508c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castagnolo D, Botta L, Botta M. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344:1285. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castagnolo D, Botta L, Botta M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1526. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.01.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotha S, Seema V. Synlett. 2011:2329. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1260315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatterjee A K, Choi T-L, Sanders D P, Grubbs R H. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11360. doi: 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark J R, French J M, Jecs E, Diver S T. Org Lett. 2012;14:4178. doi: 10.1021/ol301846q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittkopp A, Schreiner P R. Chem – Eur J. 2003;9:407. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito A, Yanai H, Taguchi T. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:12239. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2004.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tantillo D J, Houk K N, Jung M E. J Org Chem. 2001;66:1938. doi: 10.1021/jo001172h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim P, Nantz M H, Kurth M J, Olmstead M M. Org Lett. 2000;2:1831. doi: 10.1021/ol005886q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung M E, Huang A, Johnson T W. Org Lett. 2000;2:1835. doi: 10.1021/ol000104e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White J D, Demnitz F W J, Oda H, Hassler C, Snyder J P. Org Lett. 2000;2:3313. doi: 10.1021/ol000200f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental and analytical data.