Abstract

Diabetes impacts tens of millions of people in the United States of America and 9 % of the worldwide population. Given the public health implications and economic burden of diabetes, the needs of people with diabetes must be addressed through strategic and effective advocacy efforts. Diabetes advocacy aims to increase public awareness about diabetes, raise funds for research and care, influence policy impacting people with diabetes, and promote optimal individual outcomes. We present a framework for diabetes advocacy activities by individuals and at the community, national, and international levels and identify challenges and gaps in current diabetes advocacy. Various groups have organized successful diabetes advocacy campaigns toward these goals, and lessons for further advancing diabetes advocacy can be learned from other health-related populations. Finally, we discuss the role of healthcare providers and mental/behavioral health professionals in advocacy efforts that can benefit their patients and the broader population of people with diabetes.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes, Advocacy, Policy

Introduction

Advocacy is often driven by the scope and public impact of an issue, in combination with a need for additional supports or resources currently unavailable. In the case of chronic health conditions, drivers include the number of people affected; disease distribution in a community, nation, or across the globe; individual and societal costs (financial, physical, and emotional); and unmet prevention and treatment needs. It has long been recognized that diabetes meets these criteria for being a public health threat in need of advocacy [1, 2].

Nearly two million people are diagnosed with diabetes in America annually [1]. Approximately 29 million Americans (over 9 % of the population and over 25 % of those over age 65) have diabetes; the vast majority have type 2 diabetes, and about 1.25 million have type 1 diabetes [3]. Worldwide the prevalence across diabetes types was estimated to be 9 % among people aged 18 and older in 2014 [4].

Diabetes is extremely expensive, both individually and societally, making treatment adherence and achievement of optimal outcomes impossible for many, especially in developing countries [5–7]. Global health expenditures on diabetes were estimated to be at least $612 billion in 2014 [8]. The US burden of diabetes-related healthcare expenditures in 2012 was estimated at $245 billion, representing a 41 % increase since 2007 and comprising 20 % of all US healthcare costs [8]. Annual US healthcare costs for a person with diabetes are estimated to be 2.3 times greater than those of people without diabetes, around $13,700/person [9].

The individual and family demands of diabetes management are great as well. Living with and managing diabetes is complex and demanding. Self-management regimens are intense: the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines for care include a combination of frequent blood glucose monitoring, oral medications, insulin calculation and administration, and careful attention to nutrition and physical activity, depending on diabetes type and individual needs. Healthcare providers (HCPs) work with individuals with diabetes to tailor treatment recommendations, maximize the benefits of adhering to the self-management regimen, minimize risk of complications, and treat complications that do arise despite those efforts [10].

In addition to the epidemic number of people affected, economic costs, and individual and healthcare system efforts needed to manage diabetes, diabetes advocacy is also driven by an imperative to reduce rampant stigma and inequality. Many people find having diabetes embarrassing, have a diminished sense of normalcy, and feel judged by a public bias that diabetes is the fault of the individual, often leading to isolation and withdrawal, low self-esteem, and nonadherence to treatment recommendations [11, 12, 13•, 14]. Additionally, there are vast disparities in health outcomes and access to high-quality care across socio-economic, geographic, and racial groups [5, 15]. Advocacy is needed to build awareness and education about diabetes worldwide in order to reduce stigma, increase access to resources, and ultimately improve the lives of people with diabetes.

The goals of this paper are to describe the landscape of diabetes advocacy activities and their impact on key outcomes, present case examples of successful diabetes advocacy campaigns, identify gaps in diabetes advocacy, and serve as a call to action to coordinate advocacy efforts, conduct rigorous advocacy research, and enhance professional advocacy engagement.

Diabetes Advocacy Framework

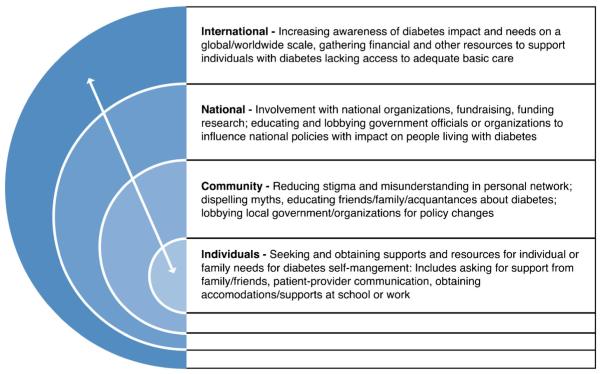

We present a framework of various domains of diabetes advocacy, representing previous and current advocacy efforts that can guide future activities and research. We define the target outcomes of diabetes advocacy as increased awareness and education about all types of diabetes, securing funding to advance diabetes research and care, policy changes benefitting people with diabetes, and improved individual diabetes outcomes, including personal empowerment and optimal health status.

As depicted in Fig. 1, the Diabetes Advocacy Framework represents activities to achieve these outcomes across four levels: (1) individual actions to meet personal and family needs, (2) community efforts to educate one’s personal network or call for change in one’s local area, (3) national activities to increase awareness, raise funds, and influence federal policy, and (4) international actions to achieve these goals on a global scale and provide assistance to resource-poor nations. Advocacy skills training programs [16, 17] and resources [18•] can help individuals become involved in advocacy (Table 1). In the following section, we describe activities at each level of the Diabetes Advocacy Framework.

Fig. 1.

Diabetes advocacy across four levels

Table 1.

Diabetes advocacy resources and toolkits

| Organization | Location | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| International Diabetes Federation |

http://www.idf.org/advocacy-toolkit | Guidelines and checklist for international advocacy |

| Summary of United Nations priorities | ||

| Sample materials (letters, press releases) | ||

| American Diabetes Association |

http://www.diabetes.org/advocacy/ | Guidelines and checklists for community and national advocacy |

| Links to contact elected officials | ||

| Advocacy skills training resources | ||

| Sample materials (speeches, media) | ||

| American Association of Diabetes Educators |

http://www.diabeteseducator.org/PolicyAdvocacy/ | Guidelines for community and national advocacy |

| Summary of state and federal legislation priorities |

||

| Links to contact elected officials | ||

| Educational materials about key advocacy issues |

||

| JDRF | http://advocacy.jdrf.org/ | Educational materials about key advocacy issues |

| Links to contact elected officials | ||

| Links to petitions and social media | ||

| Diabetes Advocates | http://diabetesadvocates.org/ | Advocacy skills training resources |

| http://diabeteshandsfoundation.org | Links to social media | |

| Summary of federal legislation priorities | ||

| Educational materials about key advocacy issues |

Individual Level

Advocacy on the individual level involves individuals, families, and HCPs taking action to obtain support and resources for the needs of specific people with diabetes. This includes individuals/families engaging in self-advocacy, such as seeking assistance from family, friends, or coworkers, requesting accommodations from school systems or employers, and communicating care-related needs and preferences to HCPs and insurers. HCPs may also advocate on behalf of their patients (e.g., to substantiate medical necessity of a service to a payer, to request a patient’s employer/school provide appropriate accommodations).

Individual advocacy strengthens education and awareness, and data from other conditions suggest that benefits may also include greater personal empowerment (i.e., sense of efficacy to effect change, participation in healthcare decisions) [19–21]. Fostering diabetes self-advocacy skills (e.g., effective patient–provider communication, navigating the healthcare and payer systems) is acknowledged as critically important [22, 23], and some behavioral interventions teach individuals self-advocacy strategies [24, 25]. For example, novel “Photovoice” programs approach health advocacy through art by encouraging participants to express their experiences, advocate for their needs, and communicate with viewers through photography [21, 26]. In sum, the individual level represents discrete skills and actions taken to meet the unique needs of specific people and families living with diabetes; advocating for the needs of larger groups occur in the next level: community.

Community Level

The goal of community-level advocacy is to improve the situations of individuals in the local community who face common challenges or barriers. Activities include efforts to reduce stigma and misconceptions about diabetes through personal actions such as dispelling myths and educating one’s personal network about diabetes. This level also involves lobbying local government officials and organizations for changes in policies that affect people with diabetes. Local healthcare organizations/centers and chapters of national organizations (e.g., JDRF, American Diabetes Association [ADA]) often lead community advocacy activities including local fundraising efforts, awareness campaigns, and supportive programming for patients/families such as educational events and diabetes screenings/health fairs. One creative approach to community-level advocacy is the development of college courses for aspiring healthcare professionals to gain in-depth education and simulation experiences related to diabetes [27], which will help prepare future providers to meet the needs of patients with diabetes. In sum, the community level is comprised of individual or group actions taken to meet the common needs of a community of people and families living with diabetes; advocating for policy changes that affect even larger populations of people with diabetes occur in the next level: national.

National Level

National advocacy aims to influence policies and resources impacting the nationwide population of individuals with diabetes. Activities include individuals and groups of various sizes participating in diabetes organizations, fundraising for research, and educating and lobbying government officials or organizations around national policies. Efforts at this level often directly influence state and local policies through governmental/organizational hierarchies. National organizations such as the ADA have a history of successful advocacy resulting in federal laws to fight discrimination and protect individuals’ rights at work and school [28–30, 31••]. For example, ADA’s Safe at School program has made it permissible for students to safely conduct diabetes management tasks during the school day in public school systems across the country [32, 33]. At the national level, successes are attributed to individual actions and cooperative efforts among multiple national organizations. For example, in partnership with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the ADA helped to create the National Diabetes Education Program [28], a feat that could not have occurred without collaboration on the national scale. The 2015 ADA Standards of Medical Care include, for the first time, a section on diabetes advocacy [3], highlighting its importance to standard diabetes management. In sum, the national level includes individual and organizational actions that aim to influence federal policies affecting people and families living with diabetes across the country; beyond national borders, advocacy efforts impacting people across the globe occur in the next level: international.

International Level

Like other non-communicable diseases, diabetes has historically been marginalized on the global health agenda due in large part to often being perceived as the result of individual choices, with little recognition of the social and genetic determinants [34]. International advocacy emphasizes increasing awareness about diabetes impact and needs on a global scale and gathering financial and other resources to support individuals with diabetes across national borders who lack access to adequate care [35].

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) is an umbrella organization of over 230 national diabetes associations in 170 countries and territories across the globe that leads international diabetes advocacy [36]. The aims of the IDF are to influence policy, increase public awareness, encourage health improvement, promote the exchange of high-quality information about diabetes, and provide education for people with diabetes and their HCPs. IDF’s international advocacy activities include the 2006 United Nations Resolution on Diabetes (United Nations Resolution 61/225) which encourages all UN member states “to develop national policies for the prevention, treatment, and care of diabetes in line with the sustainable development of their health-care system” [37, 38]. The 2011 IDF Diabetes Road Map Programme called for world leaders to invest in and coordinate efforts to combat diabetes through four central messages: “Diabetes is a major global threat to human security and prosperity; The global failure to invest in diabetes has led to the current crisis; The news is bad but we have solutions; Diabetes affects everyone and requires a collective response” [39]. These campaigns have forced the world to take seriously a disease that previously had not been well understood or resourced. In addition to promoting global awareness, other aspects of how the IDF functions can inform effective advocacy at national, local, and individual levels. For example, embedded within the IDF’s diabetes awareness slogans are important educational messages: for example, “Diabetes is Preventable” offers education about changing diet and physical activity. In addition, the IDF often focuses advocacy for specific subgroups (e.g., women with gestational diabetes, youth with type 1 diabetes) in order to deliver targeted education and resources. In sum, international advocacy aims to bring diabetes information into global awareness and to improve the lives of individuals and communities living with diabetes in all parts of the world.

Across Levels

Health advocacy has been conceptualized as a series of activities that cross multiple levels [40, 41•], and our framework also acknowledges the potential for dynamic transactions between levels. For example, an individual who asks a coworker for assistance with a diabetes management task at work may educate the coworker about diabetes, which can result in immediate individual benefits. Rippling effects among the coworker’s friends and family can impact communities and beyond by reducing diabetes myths and potentially inspiring someone to participate in an awareness walk, lobby their representative for a diabetes-related policy change, or donate to the IDF. Likewise, school-related advocacy efforts by national diabetes organizations can provide public resources that equip parents to obtain needed supports for diabetes management at school [42, 43] and have the potential to change state and federal policies related to school staff training requirements for diabetes management [44]. Individually, parents often must ensure the policy is applied in their child’s case. In the following section, we present case studies of successful diabetes advocacy activities that cross individual, community, national, and international levels.

Case Studies in Diabetes Advocacy Across Levels

Patient Hackers Heard at the FDA and Beyond: the Nightscout Project

Despite rapidly advancing diabetes care, many unmet needs remain for individuals who must deal with the practicalities of daily management, such as fear of hypoglycemia, anxiety associated with leaving children with diabetes unattended, and the demands of frequent blood glucose monitoring and complex insulin adjustments throughout the day and overnight. A grassroots group of patients and parents called Nightscout (or “CGM in the Cloud”) developed a crowd-sourced open-source software platform that allows real-time access to glucose data from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems via the web [45]. By giving individuals and families access to their glucose data through any web-connected device, this technology offers information and peace of mind. In 2014, Nightscout gained momentum in the diabetes community and founded a Facebook group; within 1 year, their members numbered over 11,000 [46]. The group has been bolstered by #WeAreNotWaiting, a social media advocacy campaign encouraging patients and providers to take device and software development into their own hands. Nightscout has gained attention from national media, including features in the Wall Street Journal [47] and Microsoft [48], and an informational meeting with the FDA [49]. Ultimately, individual and community advocacy through Nightscout has advanced dialogue about the need for more connected devices and a faster-moving environment for development of technologies people with diabetes can use in their daily lives. Indeed, in early 2015, the FDA approved remote-monitoring technology from Dexcom, a CGM manufacturer, faster than expected and down-classified the secondary display of CGM data, such that applications that display these data will no longer be subject to FDA premarket review [50]. Nightscout exemplifies how advocacy emerging from a small group of individuals can capture the attention of the local and national diabetes community, engage national organizations, and impact regulatory policy.

From the Mouths of Babes: JDRF Children’s Congress

The NIH Special Diabetes Program is a US Congressional program that allocates research specifically dedicated to type 1 diabetes beyond the standard congressional appropriations to each NIH institute. It has historically been an annual program, with no guarantee of renewal each year. Advocacy efforts, including the JDRF Children’s Congress, aim to secure its renewal [16, 51]. Every other year, they invite applications from children with diabetes to become delegates, and over 150 children from all 50 states and Washington, DC meet with elected congressional officials. Since it began in 1999, there have been eight biennial Children’s Congresses, with over 1000 children serving as delegates. In 2011, the Children’s Congress helped secure a promise from the FDA for artificial pancreas technologies guidance. In 2012, 85 % of all members of Congress met with Children’s Congress Delegates. So far, the Special Diabetes Program has been renewed each time it has come before Congress [51]. This program is an example of individuals becoming involved in the national level of advocacy.

Bridging the Information Divide: the PLAID Journal

There has long been a divide between the access that people with diabetes and their care providers have to information about new developments and research, due in large part to the antiquated paternalistic notion of Physician Knows Best and logistical barriers including access to medical and scientific journals. With the proliferation of Open Access journals since the late 1980s, there is broader and quicker public access to scientific information. Although the gap persists, advocacy efforts have helped to shrink the divide between people with diabetes and the scientific community. For example, in 2014, Martin Wood, diabetes advocate and Director of the Medical Library at Florida State University, founded the People Living with And Inspired by Diabetes (PLAID) Journal. PLAID represents a forum for collaboration among people with diabetes, providers, and diabetes researchers. The mission of this Open Access journal housed electronically in a major university medical library is to encourage and facilitate dialogue and collaboration in research relevant to the lives of people with diabetes [52]. This is an example of an individual advocating for and obtaining support from a diabetes community to build a platform that will have national and international contributors and readers. Ultimately, PLAID will assist in further narrowing the communication divide and providing benefits to individuals and communities of people with diabetes. This represents advocacy spanning all four levels in our framework.

Access to Insulin for Children with Diabetes Across the World: IDF’s Life for a Child Program

Access to education, insulin, and necessary diabetes care supplies remains sparse in developing countries. Globally, inadequate access to insulin remains the most common cause of death in children with diabetes [53], and the estimated life expectancy of a newly diagnosed child with diabetes is under 1 year in some areas [54]. Given low awareness and financial support, the IDF partnered with several diabetes advocacy groups to establish the “Life for a Child” program to provide insulin and care to children with diabetes in developing countries [55]. The program currently helps over 15,000 youth with diabetes in 48 countries. To increase community engagement and awareness of the program, Partnering for Diabetes Change created the “Spare a Rose Save a Child” campaign, encouraging individuals to buy one less rose at Valentine’s Day and donate the saved money to Life for a Child. In its first year, Spare a Rose raised over $3000 in 1 week and generated significant discussion on social media [56]. In each of the subsequent 2 years, the campaign raised over $25,000 from hundreds of individual donations, providing a year of life to 400–500 children per year. This represents an over eight-fold increase in donations from the first year. The astounding growth of the Spare a Rose program illustrates the impact of advocacy across levels, from community mobilization to individual donations, with international impact.

Raising a Voice for More Accurate Meters and Strips

Blood glucose meters and strips are the basic tools used by people with all types of diabetes to guide lifestyle and treatment decisions based on current blood glucose. Inaccuracies in these tools can lead to errors in blood glucose management, incorrect dosing of insulin and medication, and ultimately increased risk of complications or hypoglycemia. In a Diabetes Technology Society Meeting in May 2013, FDA representatives, industry leaders, and HCPs all acknowledged that some available blood glucose meters did not meet the accuracy standards for which they were originally approved [57]. In response, the diabetes online community created the “Strip Safely” campaign to raise awareness of the dangers of device inaccuracies and the need for greater attention to accuracy [58]. Using social media, individual advocates spread awareness and rallied hundreds of people to provide feedback to the FDA through public docket comments on drafted blood glucose monitoring standards. The effort resulted in 556 comments on the public docket (approximately 400 from people with diabetes), the first-ever live FDA–patient online chat on diabetes and glucose monitoring devices [59, 60], and an in-person FDA–patient meeting on the unmet needs in diabetes. The FDA publicly thanked the diabetes community for mobilizing input from people with diabetes on regulatory standards and encouraged future work together [61]. This program brought individual advocacy into community mobilization to facilitate powerful conversation on national regulatory policy impacting people with different diabetes types.

Challenges and Gaps in Diabetes Advocacy

Despite the successes illustrated by these case studies and other important diabetes advocacy campaigns, challenges and gaps in advocacy remain. Appropriate resources for care and research are still lacking, public misunderstanding about the seriousness of diabetes is common, and stigma around prevention and management of the disease abounds. An ADA study found that focus group participants viewed diabetes as only moderately severe compared to cancer and heart disease, which were perceived as very serious [62]. These beliefs persist despite the grave complications of diabetes, including hypoglycemia, amputations, blindness, and kidney failure. Another barrier is diabetes stigma, where the disease is perceived as due to a failure of personal responsibility. The associated “shame and blame” arise from beliefs that diabetes is only caused by laziness or overeating and not understanding the sociocultural or genetic factors of developing the disease [14]. Other challenges also stand in the way of widespread, coordinated attention: the relatively small population with type 1 diabetes acts as a disincentive for industry investment and research [63], and people with type 2 diabetes have less organized advocacy, fewer resources, and lower public visibility due to stigma and self-blame.

In the face of these barriers, what can we learn from other successful disease advocates? A report on HIV/AIDS advocacy outlines five priorities for advocates: gaining attention, being prepared with knowledge and solutions, creating community, enforcing accountability, and inspiring leadership [64]. The diabetes community has assets in the form of knowledge, passionate community, and smart leadership. However, public attention and accountability are key elements which are needed but lacking in the drive to stimulate coordinated action. In recent years, public acts of patient mobilization and protests sparked mainstream interest in their respective conditions. For example, political demonstrations by the HIV/AIDS group ACT UP [64] and breast cancer advocates [65] have led the FDA, major pharmaceutical companies, and researchers to engage patients to consult on clinical trial design, to increase access to new therapies, and to enhance accountability from all stakeholders for improving outcomes [64–67].

Call to Action

Research Priorities

While we do not propose to set a specific scientific agenda for diabetes advocacy, we provide several suggestions as advocates move forward in their work, based in part on other well-documented proposals for communities and advocacy [68, 69]. A research agenda for diabetes advocacy is intended to strengthen and support the roles of advocates and champions of diabetes. One of the primary goals is to increase the rigor associated with understanding the impact of advocacy by (1) identifying distinct metrics appropriate for each level of advocacy (i.e., metrics for community advocacy should be different than national advocacy) and (2) broadening target outcome measures beyond only financial ones. The measuring sticks currently used to determine whether advocacy efforts are making progress largely focus on funding and resources, and these do not capture the richness or progression of these efforts. While some metrics may show up in strategic plans, they may be aspirational and on larger scales. We encourage small achievable metrics that are linearly linked—in other words, identify each step toward a loftier goal of the advocacy effort and select an appropriate measure to determine if each step has been achieved. For example, our earlier example about NightScout may include incremental outcomes that are smaller and easier to achieve (e.g., increase visits to website to read about NightScout, increase in uptake of system components). In addition, they may be interested in linking to outcomes that are more distal and indirectly linked, but equally important (e.g., users’ quality of life or objective health outcomes). It may also be beneficial to employ quality improvement strategies [70] to systematically conduct and evaluate small-scale cycles of trial and error. It is well documented in education, business, and health arenas that reinforcement of the process (versus the outcome) promotes better outcomes. Focusing on these small steps and metrics sets the stage for greater rigor around advocacy outcomes.

Developing infrastructure is a critical consideration when attempting to infuse rigor into the evaluation of diabetes advocacy outcomes. Many advocacy organizations, which are often non-profits, operate on small budgets and rely on volunteers to accomplish mission-aligned goals. Seeking pro bono partnerships with experienced investigators in conducting clinical research will help to ensure that an infrastructure exists for evaluating the impact of advocacy. Research scientists can bolster the range of outcomes considered (e.g., measuring quality of life changes for participants and organizations) and can calculate and compare the cost-effectiveness of programming via community organizations versus medical institutions. This type of collaboration among communities and stakeholders is essential to strengthen the rigorous evaluation of advocacy [68].

Healthcare Providers as Advocates

The most traditional provider advocacy role is on behalf of an individual patient, although a wide range of professional advocacy activities have evolved. On the individual level, a patient may need a letter written or form completed to support medical necessity of a service or supply to ensure equal rights at school or at work (e.g., 504 Plans, paperwork for Family Medical Leave Act protection), or they may need help with critical decision making. Providing for these needs is a form of advocating for an individual patient’s rights and needs [71, 72, 73••]. Beyond the individual level, broader efforts can affect groups of patients and potentially large subsets of the diabetes population. In routine care provision, HCPs can encourage patients and their families to participate in advocacy efforts, such as letter writing to elected officials or fundraising for diabetes organizations. They can also post literature on local, national, and international advocacy opportunities in clinic space or refer patients to advocacy organizations’ websites.

HCPs can also serve more formally through volunteer activities or as members of organizational boards or committees. With their expertise, HCPs are well positioned to provide community education, from local events such as health fairs or talks at a community center or school classroom to larger scales such as newspaper, radio, website, or podcast appearances. HCPs can also leverage their expertise to participate in legislative efforts, such as by meeting with or writing letters to elected officials about diabetes-related issues [73••, 74]. HCPs often serve on national and international organization committees to create policy statements that carry weight in government policy decision-making [32].

Given mounting evidence of the mental/behavioral health comorbidities of diabetes and their implications for poor health outcomes [75], mental/behavioral health providers also have an important role to play in advocating for widespread access to appropriate services. Along with other professional stakeholders, mental/behavioral health professionals and their HCP colleagues are ideally poised to advocate individually and on a larger scale for integration of mental/behavioral services into routine diabetes care, annual mental/behavioral health screenings, parity in insurance reimbursement for mental/behavioral health services, and funding for research to assess the cost-effectiveness and efficacy of new healthcare delivery models that emphasize and promote mental/behavioral health [76].

Conclusions

Diabetes represents a massive threat to public health that has considerable physical, financial, and emotional impacts on the lives of millions of people across the globe. While advances in diabetes treatments are growing rapidly, people living with all forms of diabetes continue to face daunting challenges. Resources for many are difficult to access, and individuals and families often must fight uphill battles to obtain their necessary treatments and supplies. Unfortunately, diabetes remains on the fringe of policy makers’ agendas.

The Diabetes Advocacy Framework posits that successful advocacy results from dynamic interactions across levels, from individuals and communities impacting national and international systems to policies and actions that ultimately benefit patients living with diabetes. Only through coordination and collaboration can efforts cohere into a collective movement. Issues remain in improving public education about diabetes and increasing coordination between isolated groups, and successes in other health conditions tell us that these are solvable problems and can be addressed by focusing on education and accountability.

At a recent annual advocacy skills training workshop led by the Diabetes Advocates organization, prominent HIV/AIDS activist Michael Manganiello announced to the crowd of diabetes advocates, “You guys have energy and you’re moving towards something. I wouldn’t call what you have a movement, yet” [67]. We agree: there is still work left to do. The advocacy success stories we highlight exemplify that a single individual or a small group can make a remarkable impact that influences the lives of people with diabetes across the globe.

Whether advocating for individuals or groups large or small, there are numerous ways individuals, HCPs, and the scientific community can advance advocacy to support people living with diabetes. Our individual patients and the communities in which we and they live, on every scale, can benefit from our efforts. Please heed this call to action, consider how you can get involved, and advocate for people with diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The work of Marisa E. Hilliard, Ph.D., and Barbara J. Anderson, Ph.D., on this paper was supported by the NIH (K12 DK 097696, PI: B. Anderson) and in part by The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. Dr. Anderson is also supported by JDRF and NIH (R01 DK 095273). Korey K. Hood, Ph.D., is supported by grants from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and NIH (R01 DK 901470, DP3 DK 104059). Sean Oser, M.D., is supported by the NIH (DP3 DK 104054).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest Marisa E. Hilliard, Sean M. Oser, Kelly Close, Nancy Liu, Korey K. Hood, and Barbara J. Anderson declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Marisa E. Hilliard, Email: marisa.hilliard@bcm.edu.

Sean M. Oser, Email: soser@hmc.psu.edu.

Kelly L. Close, Email: Kelly.close@diaTribe.org.

Nancy F. Liu, Email: nancy.liu@diaTribe.org.

Korey K. Hood, Email: kkhood@stanford.edu.

Barbara J. Anderson, Email: bja@bcm.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Kaplan RM, Vinicor F, Smith L, Norman J. If diabetes is a public health problem, why not treat it as one? A population-based approach to chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21:159–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02908297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright A. The public health approach to diabetes. Am J Nurs. 2007;107:39–42. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000277827.82300.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Statistics report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valenzuela JM, Seid M, Waitzfelder B, Mayer-Davis EJ, on behalf of the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group Prevalence of and disparities in barriers to care experienced by youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1369–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randall L, Begovic J, Hudson M, Umpierrez G. Recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis in inner-city minority patients: behavioral, socioeconomic, and psychosocial factors. Diabet Care. 2011;34:1891–1896. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith-Spangler CM, Bhattacharya J, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Diabetes, its treatment, and catastrophic medical spending in 35 developing countries. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:319–26. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Diabetes Federation . IDF diabetes atlas update poster. 6th International Diabetes Federation; Brussels: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–46. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association Children and adolescents. Sec. 11. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;39(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillson R. Embarrassing diabetes. Pract Diabet. 2014;31:313–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vishwanath A. Negative public perceptions of juvenile diabetics: applying attribution theory to understand the public’s stigmatizing views. Health Commun. 2014;29:516–26. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.777685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Wolf A, Liu N. The numbers of shame and blame: how stigma affects patients and diabetes management. Diatribe. 2014 Accessed from http://diatribe.org/issues/67/learning-curve on March 16 2015. This is an important study demonstrating the substantial stigma experienced by people with all types of diabetes, highlighting the critical need for advocacy. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browne JL, Ventura A, Mosely K, Speight J. ‘I call it the blame and shame disease’: a qualitative study about perceptions of social stigma surround type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, Anton B. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors—an endocrine society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:e1579–e1639. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turvey J. Kids count in Congress. MLO-Online 2005. Accessed from http://www.mlo-online.com/articles/200508/0805washreport.pdf 17 Mar 2015. [PubMed]

- 17.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Burris A. Community-based participatory approach: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Publ Health. 2010;100:2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Izumi BT, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Sand SL. The one-pager: a practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Commun Health Partnersh. 2010;4:141–147. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0114. This is a useful and practical guide to use research for effective advocacy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallerstein N. Health Evidence Network Report. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2006. What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiltshire J, Cronin K, Sarto GE, Brown R. Self-advocacy during the medical encounter: use of health information and racial/ethnic differences. Med Care. 2006;44:100–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196975.52557.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madrigal DS, Salvatore A, Casillas G, Casillas C, Vera I, Eskenazi B, et al. Health in my community: conducting and evaluating PhotoVoice as a tool to promote environmental health and leadership among Latino/a youth. Prog Commun Health Partnersh. 2014;8:317–29. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monaghan M, Hilliard ME, Sweenie R, Riekert K. Transition readiness in adolescents and emerging adults with diabetes: the role of patient–provider communication. Curr Diabet Rep. 2013;13:900–8. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0420-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, Wood D. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ-transition readiness assessment questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;36:160–171. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmas W, Findley SE, Mejia M, Carrasquillo O. Results of the Northern Manhattan community outreach project: a randomized trial studying a community health worker intervention to improve diabetes care in Hispanic adults. Diabet Care. 2014;37:963–969. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant C, Pan J. A comparison of five transition programmes for youth with chronic illness in Canada. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:815–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Necheles JW, Chung EQ, Hawes-Dawson J, Schuster MA. The teen photovoice project: a pilot study to promote health through advocacy. Prog Commun Health Partnersh. 2007;1:221–229. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood FG, Payne-Foster P, Kelly R, Lewis DM. Learning and living diabetes: development of a college diabetes seminar course. Diabet Spectrum. 2011;24:42–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene MA. Diabetes legal advocacy comes of age. Diabet Spectrum. 2006;19:171–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin JW. Employment rights of people with diabetes: changing technology and changing law. J Diabet Sci Technol. 2013;7:345–9. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graff MR. AADE legislative advocacy: perspectives on prevention. Diabet Educ. 1997;23:241. doi: 10.1177/014572179702300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Diabetes Association. Diabetes advocacy. Sec 14 In standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S86–7. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S017. This is the first time the American Diabetes Association has recognized the importance of advocacy in its Standards of Medical Care, highlighting the growing recognition of advocacy as an integral component of living with diabetes and reflecting the many achievements of national and international organizations to promote advocacy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siminerio JM, Dimmick B, Jackson CC, Deeb LC. The crucial role of health care providers in advocating for students with diabetes. Clin Diabet. 2012;30:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood JM. Protecting the rights of school children with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:339–44. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Author N. Towards the policy reforms we need to tackle NCDs—an interview with Badara Samb. Diabet Voice. 2011;56:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pramod S. Non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) and diabetes: advocacy for support services in resource-poor nations. Endocr Abstr. 2012;29:P519. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colaguiri R, Short R, Buckley A. The status of national diabetes programmes: a global survey of IDF member associations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United Nations Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 20 December 2006. Accessed from http://daccess-ods.un.org/TMP/9047121.4056015.html 31 Mar 2015.

- 38.Siegel K, Venkat Narayan KM. The unite for diabetes campaign: overcoming constraints to find a global policy solution. Glob Health. 2008;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mbanya JC. Calling the world to action on diabetes. Diabet Voice. 2011;56:15–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Zimmerman MA, Checkoway BN. Empowerment as a multi-level construct: perceived control at the individual, organizational, and community levels. Health Educ Res. 1995;10:309–27. [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Galer-Unti RA, Tappe MK, Lachenmayr S. Advocacy 101: getting started in health education advocacy. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:280–8. doi: 10.1177/1524839903257697. This resource provides practical strategies for health advocacy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siminerio LM, AlbaneseO’Neill A, Chiang JL, Hathaway K, Jackson CC, Weissberg-Benchell J, Wright JL, Yatvin AL, Deeb LC. Care of young children with diabetes in the child care setting: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. 2014;37:2834–2842. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Diabetes Education Program Helping the student with diabetes succeed: a guide for school personnel. 2010 Accessed from http://www.ndep.nih.gov/media/NDEP61_SchoolGuide_4c_508.pdf 16 Mar 2015.

- 44.California Supreme Court Ruling Supports Access to Insulin for California Students. Accessed from http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/parents-and-kids/diabetes-care-at-school/access-to-insulin-for-california-students-deprived.html 16 Mar 2015.

- 45.Nightscout. 2015 Accessed from http://www.nightscout.info/16 Mar 2015.

- 46.CGM in the Cloud Facebook group Accessed from https://www.facebook.com/groups/cgminthecloud/16 Mar 2015.

- 47.Linebaugh K. Citizen hackers tinker with medical devices. Wall Street J. 2014 Accessed from http://www.wsj.com/articles/citizen-hackers-concoct-upgrades-for-medical-devices-1411762843 31 Mar 2015.

- 48.Riordan A. Open source and the cloud: changing the lives of people with type 1 diabetes. Microsoft News 2014. Accessed from http://news.microsoft.com/features/open-source-and-the-cloud-changing-the-lives-of-people-with-type-1-diabetes/31 Mar 2015.

- 49.Leibrand S. How and why we are working with the FDA. 2014 Accessed from http://diyps.org/2014/10/12/how-and-why-we-are-working-with-the-fda-background-and-a-brief-summary-of-the-recent-meeting-with-the-fda-about-the-nightscout-project/31 Mar 2015.

- 50.US Food and Drug Administration FDA approval of Dexcom Share. 2015 Accessed from http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm431385.htm 31 Mar 2015.

- 51.JDRF Children’s Congress. Accessed from http://cc.jdrf.org/about-jdrf-childrens-congress/26 Mar 2015.

- 52.PLAID Accessed from http://theplaidjournal.com/index.php/CoM/index 26 Mar 2015.

- 53.Gale EAM. Dying of diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368:1626–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beran D, Yudkin JS, de Courten M. Access to care for patients with insulin-requiring diabetes in developing countries: case studies of Mozambique and Zambia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2136–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.IDF Life for a child. Accessed from http://www.idf.org/lifeforachild/the-programme 31 Mar 2015.

- 56.P4DC Spare a rose. Accessed from http://www.p4dc.com/spare-a-rose/faq/31 Mar 2015.

- 57.Kern R. Blood glucose meter accuracy problems acknowledged by FDA, industry, and clinicians. The Gray Sheet. 2013 Accessed from https://www.pharmamedtechbi.com/publications/the-gray-sheet/%2039/21/blood-glucose-meter-accuracy-problems-acknowledged-by-fda-industry-and-clinicians 15 May 2015.

- 58.Strip Safely About the StripSafely collaboration. Accessed from http://www.stripsafely.com/49-2/15 May 2015.

- 59.Strip Safely. 556, Thanks—congratulations DOC! Accessed from http://www.stripsafely.com/556-thanks-congratulations-doc/15 May 2015.

- 60.diaTribe FDA hosts the first live patient chat on diabetes and glucose monitoring devices; how you can influence FDA guidelines. Accessed from http://diatribe.org/issues/63/new-now-next/4 15 May 2015.

- 61.FDA FDA–patient dialogue on the unmet needs in diabetes. Accessed from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForPatients/Illness/Diabetes/UCM427478.pdf 15 May 2015.

- 62.Parker-Pope T. Diabetes: underrated, insidious and deadly. New York Times 2008. Accessed from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/01/health/01well.html 31 Mar 2015.

- 63.Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Drug Discovery, Development and Translation Transforming clinical research in the united state: challenges and opportunities: workshop summary. 2010 Accessed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK50888/31 March 2015. [PubMed]

- 64.Manganiello M, Anderson M. Back to basics: HIV/AIDS advocacy as a model for catalyzing change. Accessed from http://hcmstrategists.com/wp-content/themes/hcmstrategists/docs/Back2Basics_HIV_AIDSAdvocacy.pdf 31 Mar 2015.

- 65.Bazell R. HER-2: the making of herceptin, a revolutionary treatment for breast cancer. Random House. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Collyar D. How have patient advocates in the United State benefited cancer research? Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:73–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manganiello M. What has been accomplished by other patients (and how) MasterLab; Orlando: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson JA, Edwards AL. Evidence and advocacy: are all things considered? Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174:1856–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trickett EJ, Beehler S, Deutsch C, Trimble JE. Advancing the science of community-level interventions. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1410–1419. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Varkey P, Reller MK, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:735–9. doi: 10.4065/82.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arent S. The role of diabetes healthcare professionals in diabetes discrimination issues at work and school. Diabet Educ. 2002;28:1021–7. doi: 10.1177/014572170202800616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwartz L. Is there an advocate in the house? The role of health care professionals in patient advocacy. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:37–40. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73••.Lorber D, Gavlak G. Stopping diabetes through advocacy: the role of health care professionals. Clin Diabet. 2012;30:179–82. This important paper provides concrete examples of how healthcare professionals can and should become advocates for their patients and for the greater diabetes community. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saxe JS. Promoting healthy lifestyles and decreasing childhood obesity: increasing physician effectiveness through advocacy. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:546–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312:1–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ducat L, Rubenstein A, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. A review of the mental health issues of diabetes conference. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:333–8. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]