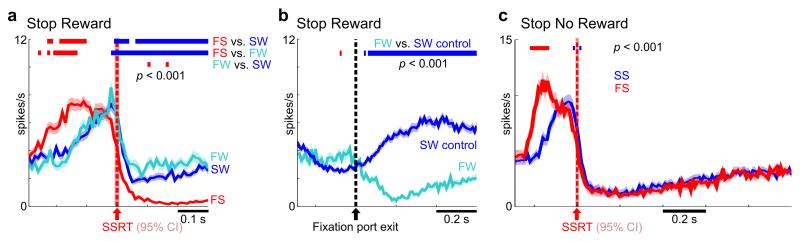

Figure 7. Post-SSRT BF activity tracked reward expectancy and behavioral performance.

(a) Population PSTHs (mean ± s.e.m.) of BF bursting neurons in the Stop Reward Task for the three trial types. Horizontal bars indicate significant (p<0.001) decreases (blue) or increases (red) in activity. Activity in failure-to-stop trials was significantly lower than the other two trial types after SSRT. Activity in failure-to-wait trials was significantly higher than successful wait trials during the waiting period after SSRT. Significant differences in activity before SSRT disappear when SSDs are properly matched (Fig. 5a). (b) Population PSTHs of BF bursting neurons in the Stop Reward Task for failure-to-wait and successful wait trials, aligned at fixation port exit of failure-to-wait trials (see Methods for details). Activity in failure-to-wait trials was significantly higher than latency-matched successful wait trials and peaked right before fixation port exit. After fixation port exit, activity in failure-to-wait trials immediately decreased relative to successful wait trials. (c) Population PSTHs of BF bursting neurons in the Stop No Reward Task for the two trial types. There was no significant difference in neuronal activity between failure-to-stop and successful stop trials after SSRT. Again, significant differences in activity before SSRT disappear when SSDs are properly matched (Fig. 5b). (n=161 neurons for Stop Reward Task, n=114 for Stop No Reward Task). The red shaded areas indicate the 95% CI of SSRT estimate (n=17, 20 sessions).