Abstract

This study examines the relationship between student substance use and school-level parental involvement as reported by administrators. Questionnaires were administered to school administrators and 111,652 students in 1,011 U.S. schools. Hierarchical logistic regression analyses conducted on 1998–2003 data from students and administrators indicate significantly lower prevalence of alcohol use among 8th graders in schools where administrators reported high parental involvement. Overall, administrators’ reports of high parental involvement were unrelated to prevalence of substance use among 10th graders, and were associated with higher prevalence of alcohol use among 12th-graders. Implications and limitations are discussed, along with suggestions for future research.

Substance use among American secondary school students continues to be a major social problem, generating many research efforts aimed at identifying individual-and contextual-level risk and protective factors (Hawkins & Catalano, 1990; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Jessor, 1993). While much of this research is at the individual level examining the role of family and peer characteristics on individual substance use behavior (e.g., Brook, Nomura, & Cohen, 1989), more recently there is an emphasis on examining the impact of school organizational characteristics on student problem behavior. Measures of school characteristics, including features of the school building such as upkeep (Kumar, O’Malley, & Johnston, 2008), age of the building (Hellman & Beaton, 1986), and school demographics—type (public/private), size, overall socioeconomic status, and ethnic composition of the school (Eitle & Eitle, 2004; O’Malley, Johnston, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Kumar, 2006)—have been examined in relation to problem behaviors such as substance use, truancy, delinquency, and violence. Some studies have found that certain more malleable school characteristics are associated with lower rates of student problem behaviors, such as orderly and disciplined school environments with a sense of school community (Gottfredson, Gottfredson, Payne, & Gottfredson, 2005); normative school values of caring, concern for others, and commitment to learning (Battistich, Schaps, Watson, Solomon, & Lewis, 2000); and disapproval of substance use behavior (Kumar, O’Malley, Johnston, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2002) and violence (Felner, Liska, South, & McNulty, 1994).

In this study we examine an important and malleable feature of the school context, one that has been the focus of a great deal of research at the individual level but not at the school level, namely, parental involvement. The underlying assumption is that the social and interpersonal climate in a school where a sizable percentage of parents are actively involved and physically present in school is likely to be very different compared to a school where such parental involvement is minimal. We hypothesized that significant school-level parental involvement—namely, volunteering at school activities and participation in parent–teacher conferences and organizations—would correspond to lower levels of substance use (marijuana, alcohol, and tobacco use among 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students.

Definition of Parental Involvement

Parental involvement is variously conceptualized (e.g., Barnard, 2004; McNeal, 1999; McWayne, Hampton, Fantuzzo, Cohen, & Sekino, 2004). Epstein and Salinas (2004) identify six kinds of parent involvement, including home involvement such as active engagement in children’s academic learning, at home and school-level involvement such as communicating with teachers and administrators, volunteering at school events, and participating in decision-making regarding school policies. Both kinds of parental involvement—individual and institutional—seem to be important in that they can have independent and synergistic effects on adolescents’ well-being. However, schools vary in both the form and frequency of these parent–school interactions.

Volunteering in school activities and participation in parent teacher conferences and organizations are the dimensions of parental involvement considered in this study. What sets this study apart from other studies in this area is that the construct, parental involvement, is examined at the institutional level and not at the individual level. For example, it is possible that in schools where many parents volunteer their time and effort to participate in school-sponsored activities or are active in parent teacher organizations, an environment of caring for all students is created. Thus, the academic and social environment within a school where school personnel report high levels of communication and interaction with parents is likely to be different from a school with low levels of communication and interaction. In this study we examine parental involvement as an aspect of the school environment based on data obtained from school administrators.

Parental Involvement and Adolescent Substance Use Behavior

Misuse of substances is known to increase during adolescence (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007). Also well established is the finding that substance use during high school years is associated with academic failure (Bachman, O’Malley, Schulenberg, Johnston, Freedman-Doan, & Messersmith, 2008; Cox, Zhang, Johnson, & Bender, 2007). A large body of research supports the claim that parental involvement is associated with improved academic attainment (Barnard, 2004; McWayne et al., 2004; Eccles & Harold, 1996; Epstein & Dauber, 1991; Hess & Holloway, 1984; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005; Sui-Chu & Willms, 1996), but less is known about the relationship between school-level parental involvement and adolescents’ substance use. Several school-based alcohol and drug prevention programs incorporate parental involvement as part of their treatment plan (Petrie, Bunn, & Bryne, 2007; Shepard & Carlson, 2003), but they do not promote parental involvement in other school-based activities that might encourage students to stay engaged in school.

Research based on Kumpfer and Turner’s (1990) social ecology model, an extension of the Hawkins and Weis (1985) social development model, suggests that positive and caring family and school environments are associated with lower substance use. Schools are being called upon to transform their social environment through parental collaboration and engagement in their child’s education and psychosocial well-being (Battistich et al., 2000; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Dryfoos, 1990; Garbarino, 1981; Haynes, 1996). Utilizing the ecological framework, Garbarino (1981) conceptualizes parental involvement as a school-level phenomenon, emphasizing that the strength and nature of the home–school relationship is variable from school to school and community to community. Thus it is likely that in addition to other demographic factors associated with the prevalence of substance use, differences in school environment determined by the percentage of parents actively involved in school related activities such as communicating with teachers, volunteering in school-based activities, and participating in parent-teacher organization may also be associated with the prevalence of substance use among secondary school students. In this study, we examine the association between the collective involvement of parents at the institutional level and the prevalence of substance use among students.

Moderating factor: Student grade level

Increased parental involvement is widely accepted as essential for school adjustment and engagement in elementary school (Epstein & Dauber, 1991; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005) and academic outcomes in secondary school (Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987; Hill & Taylor, 2004). In high school, for example, even though parents may not help directly with homework, parent involvement is associated with adolescents spending more time on completing their homework (Epstein & Sanders, 2006).

Effects of parental involvement on adolescents’ problem behaviors in the higher grades remain unclear (Eccles & Harold, 1996). Some researchers suggest that, considering adolescents’ increasing need for autonomy (Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992), it may be developmentally beneficial if parents decrease their involvement in school as adolescents move into higher grades (Green, Walker, Hoover-Dempsey, & Sandler, 2007). However, a steady increase in substance use as students move into higher grades parallels a steady decline in all types of parental involvement as students move from elementary through middle to high school (Crosnoe, 2001; Eccles & Harold, 1996; Green et al., 2007; Stevenson & Baker, 1987). It is possible, therefore, that increased parental participation in school activities and programs may be more beneficial in decreasing the prevalence of substance use among 10th- and 12th-grade students as compared to 8th-grade students.

Moderating factor: School socioeconomic status

Effects of parental involvement on student outcomes may vary as a function of socioeconomic status (SES) and level of parental education (Lee & Bowen, 2006; McNeal, 1999; Stevenson & Baker, 1987; Weiss et al., 2003). Several studies suggest that high-SES parents are more involved in their children’s education than low-SES parents (Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1987; Sui-Chu & Willms, 1996). Well-educated parents interact with teachers with more ease and feel more comfortable being involved in school activities (Garbarino, 1981; Lareau, 1987, 1996). The interactive effects of parental education and SES on adolescents’ outcomes are mixed. Lee and Bowen (2006) report that, while college-educated parents were significantly more involved in school, parental involvement in school had a beneficial effect on children’s achievement regardless of parental educational level. In contrast, McNeal (1999) reports that parental involvement in parent–teacher organizations had a more beneficial effect on achievement among high-SES European-American students than among minority low-SES students. Lareau (1987) and McNeal (1999) contend that the cultural capital possessed by high-SES parents enhances the positive effects of parental involvement on their children’s achievement. Similarly, it is likely that the positive effects of parental involvement in lowering substance use rates are likely magnified in high-SES schools, while the relative social disorganization of low-SES schools may result in collective parental involvement being less effective (Elliott, Wilson, Huizinga, Sampson, Elliot, & Rankin, 1996).

Summary of Hypotheses

We hypothesize that parental involvement at the institutional level in school-related activities will vary inversely with grade level. We further hypothesize that the prevalence of substance use (daily cigarette use, heavy drinking, marijuana use, and other illicit drug use) among students will be lower in schools where administrators report that parents are more involved in school-related activities and in their children’s education (controlling student and school demographic characteristics except school SES). Finally, we propose to examine whether the effect of school-level parental involvement on students’ substance use behavior is conditional on grade level and school SES, as indicated by average parental education.

Method

Sample and Survey Procedures

This study utilizes data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) project (Johnston et al., 2007), which annually surveys nationally representative samples of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students in public and private schools, beginning in 1975 for 12th graders and in 1991 for 8th and 10th graders. Data are collected using questionnaires administered in classrooms by locally based University of Michigan representatives. The optically scanned, paper and pencil questionnaires are self-completed by students during normal class periods.

Each school is asked to participate for two years. Beginning in 1998, administrators of schools that had just completed their second year of participation in MTF have been invited to complete a questionnaire as part of the Youth, Education, and Society (YES) study, which deals with schools’ policies, programs, and practices related to substance use and other health-related matters. The YES study also assesses school administrators’ perceptions of the level of parental involvement in school. The majority of respondents are school principals (62%), followed by guidance counselors (12%), assistant principals (10%), and department heads (9%). The present analyses use 1998–2003 data from students and school administrators. The sample includes 43,505 eighth-grade students from 371 schools, 34,089 tenth-grade students from 317 schools, and 34,508 twelfth-grade students from 323 schools.

Measures

Dependent variables

Indicators of substance use include: cigarette use, alcohol use, being drunk, and marijuana use in the past 30 days; consuming five or more drinks of alcohol in a row in the past two weeks; and marijuana use and use of an illicit substance other than marijuana in the past year. These measures were dichotomized—0 = “never,” 1 = “one or more times” —because the distributions for all substance use variables are very positively skewed.

Parental involvement measures

The school administrators’ questionnaire included four indicators of school-level parental involvement.1 Two—“How active is your school’s Parent/Teacher Association or Organization (or similar parent group)?” and “Overall, how involved would you say parents of the students at your school are in their children’s education?”—are measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Very.” Two questions requested administrators to estimate the percent of students in the relevant grade who have at least one parent who a) attends meetings or talks to teachers fairly regularly during the school year, and b) does some volunteering at the school (e.g., chaperone, hall monitor, committee member). To create a single index of parental involvement, each of these latter two measures was collapsed into a five-point scale (1 = low levels and 5 = high levels) so that they are on a commensurate scale to the first two indicators. The intercorrelations of these four 5-point indicators of parental involvement were moderately high, ranging from .41 to .59. Factor analysis of the four indicators yielded a single factor, so the four were combined (arithmetic average) into a single scale. The Cronbach alpha of the parental involvement scale (Mean = 3.03, SD = .99) was .82.

Control variables

The control variables include environmental and individual factors that research suggests are associated with substance use behavior among adolescents (Guo, Hawkins, Catalano, & Abbott, 2002; Newcomb & Felix-Ortiz, 1992). At the student level, the control variables include various self-reported demographic characteristics: gender, race/ethnicity, average level of parental education, and whether they lived in two-parent households (referred to as “broken home,” coded 1 for living with both parents, and 0 otherwise). At the school level, the control variables include type of school (public or private), school size (the number of students in the relevant grade: 8th, 10th, or 12th), and urbanicity (suburban, urban, or rural); all of these have been identified in earlier research as features of the school associated with problem behavior (Eitle & Eitle, 2004; O’Malley et al., 2006). In addition, an indicator of school average SES—average parental education—was obtained by aggregating parent education, based on the average of mother’s and father’s education level from the student data, to the school level.

Analysis Plan

We first examined the descriptive statistics for the four individual measures of parental involvement and the parental involvement scale and compared these by grade. Next, we examined the relationship between aggregated parental education and school administrators’ reports of parental involvement. Multiple logistic regression for dichotomous outcome variables using HLM 6.0 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004) was the primary analytic tool to test the hypotheses. The variables of interest for predicting the various measures of substance use were the parental involvement index, parental education, and the interaction of parental involvement and parental education at the school level, adjusting for student- and school-level demographic control variables. Hierarchical modeling was utilized because of the nested nature of the data with parental involvement conceptualized and measured as a characteristic of the school context and substance use (alcohol, marijuana and cigarette) measured at the student or individual level. Hierarchical modeling also allowed for including aggregated school-level parental education—a qualitatively different construct form the individual measure of parental education—while controlling for parental education at the individual level (Hox, 2002; Kreft & de Leeuw, 1998). These analyses were conducted separately for 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. The general equation representing the hierarchical regression model predicting the log-odds of substance use is presented below:

- Level 1 model

-

Level 2 modelCombining the level 1 and level 2 equations:

Results

Table 1 presents the prevalence rates for each of the seven different substance use measures separately for 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students. Prevalence rates for all substances, licit and illicit, were significantly greater for students in the higher grades as compared to the lower grades, as expected.

Table 1.

Prevalence of substance use (various measures), 1998–2003

| Substance-Using Behavior | 8th grade N = 43,505 |

10th grade N = 34,089 |

12th grade N = 34,508 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (Percent Using) | |||

| Cigarette use in the past 30 days | 13.8 | 22.7 | 29.9 |

| Alcohol use in the past 30 days | 21.1 | 38.9 | 50.4 |

| Heavy drinking | 13.0 | 24.5 | 30.0 |

| Being drunk in the past 30 days | 7.5 | 21.3 | 32.6 |

| Marijuana use in the past 30 days | 8.4 | 18.8 | 22.0 |

| Marijuana use in the past 12 months | 14.8 | 31.1 | 36.8 |

| Illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months | 9.7 | 16.2 | 19.7 |

Note: All overall Fs were significant at the p <.001 level, and post hoc comparisons show that 8th-grade means were significantly different from 10th and 12th grades, and 10th-grade means were significantly different from 12thgrade.

The means and standard deviations for the four school-level indicators of parental involvement and the parental involvement index are presented in Table 2. Table 2 shows that administrators report significantly higher levels of parental involvement in schools where we surveyed 8th-grade students than in schools where we surveyed 10th and 12th graders. Eighth-grade school administrators report that an average of 48.7% of students have at least one parent who attends meetings or talks with teachers fairly regularly; 10th-and 12th-grade administrators report about 42%. Eighth-grade school administrators report that an average of 22.5% of students had at least one parent who did some volunteering at school, compared to 19.5% for 10th-grade administrators and 16.4% for 12th grade. Compared to 10th- and 12th-grade administrators, 8th-grade administrators report that their schools’ parent–teacher associations or organizations were more active, and that parents were more involved in their children’s education. The differences were significant in one-way analyses of variance, and post hoc comparisons for each of the four indicators and the index of parental involvement revealed that, on average, school administrators for the 8th-grade sample of schools reported higher levels of parental involvement than did school administrators for the 10th and 12th grades.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviations for school administrators’ reports of parental involvement in schools, 1998–2003

| Scale Range | 8th grade N = 371 |

10th grade N = 317 |

12th grade N = 323 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Percent of parents attending parent–teacher meetings | 0–100 | 48.71 (29.54) | 41.78 (27.75) | 42.04 (26.83) |

| Percent of parents volunteering in school | 0–100 | 22.47 (23.41) | 19.54 (20.31) | 16.37 (17.37) |

| Active parent teacher organization | 1–5 | 3.21 (1.31) | 2.77 (1.29) | 2.72 (1.26) |

| Overall parental involvement in education | 1–5 | 3.35 (.95) | 3.18 (.99) | 3.10 (0.88) |

| Parental involvement index | 1–5 | 3.21 (1.00) | 2.96 (.99) | 2.88 (.95) |

Note: All overall Fs were significant at the p <.001 level, and post hoc comparisons show that 8th-grade means were significantly different from 10th and 12th grades.

In each of the three grades, the parental involvement index was significantly positively correlated with parental education level (Table 3). We conducted one-way analyses of variance to examine the effect of—aggregated parental education on school administrators’ reported parental involvement. Schools were categorized into three equal-sized groups based on aggregated parental education. The first group, categorized as “low parental education schools,” scored 3.64 or less on the six-point aggregated parental education scale. Schools with aggregated parental education values between 3.64 and 4.08 were identified as “medium parental education schools,” and schools with aggregated parental education greater than 4.08 were identified as “high parental education schools.” There were significant overall differences among the three groups in the activity level of parent–teacher organizations (p < .001), the percentage of parents attending parent–teacher meetings (p < .001), the percentage of parents volunteering in school (p < .001), and overall involvement of parents in their children’s education (p < .001). Post hoc tests indicated that schools characterized by low and medium levels of aggregated parental education reported significantly lower levels of parental involvement compared to schools characterized by high levels of aggregated parental education.

Table 3.

Product–moment correlation of parental involvement index with parental education (aggregated) and prevalence of substance use in school (aggregated)

| Student-Level Variables Aggregated to the School Level | Parental Involvement Index (school-level variable) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 8th grade N = 371 |

10th grade N = 317 |

12th grade N = 323 |

|

| Parental education | .58*** | .58*** | .54*** |

| Cigarette use in the past 30 days | −.20*** | −.12* | .02 |

| Alcohol use in the past 30 days | −.14** | .02 | .22*** |

| Heavy drinking | −.23*** | −.09 | .16** |

| Drunk in the past 30 days | −.18*** | .04 | .18*** |

| Marijuana use in the past 30 days | −.25*** | −.18** | .03 |

| Marijuana use in the past 12 months | −.26*** | −.17** | .08 |

| Illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months | −.10 | −.12* | .03 |

p <.05,

p <.01,

p <.001

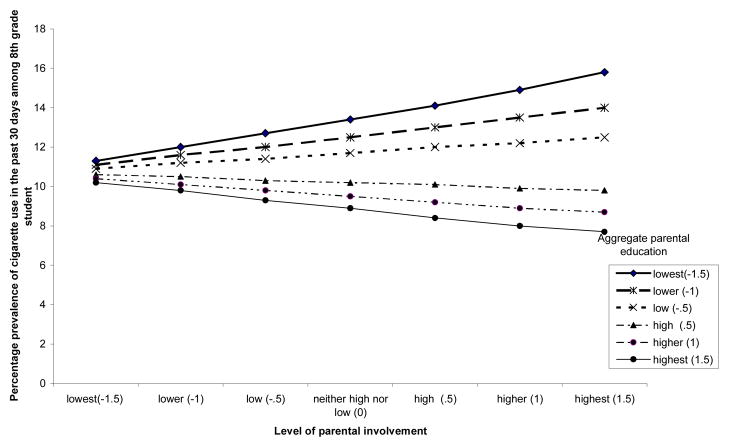

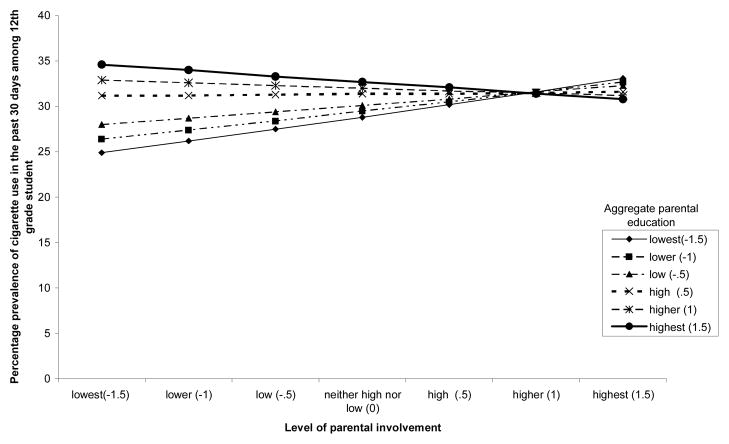

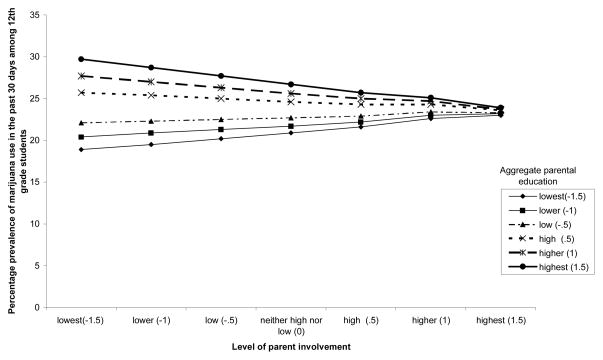

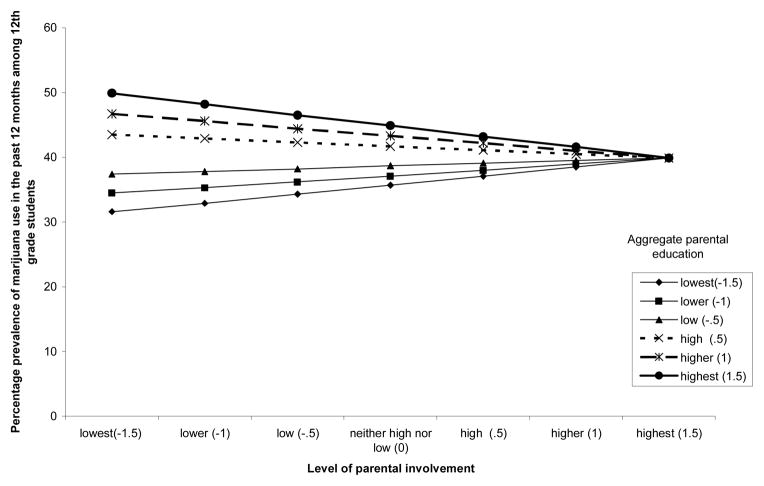

Results of Multilevel Logistic Regression Analysis

We used hierarchical logistic regressions to examine the association between level of parental involvement as reported by school administrators, aggregated parental education, and the interaction of these two school-level variables and the various dichotomous indicators of substance use, controlling for all of the student and school demographic characteristics described earlier. Table 4 presents the logistic regression coefficients of these three school-level variables of interest on the various measures of substance use. Four models predicting students’ substance use behavior are presented in Table 4 for each of the grades. In Model 1, we present the unadjusted regression coefficient for parental involvement (that is, parental involvement is the only predictor in the model). In Model 2, the regression coefficient for parental involvement adjusted for school demographic characteristics (school size, public vs. private, and urbanicity) and student demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, parental education, and broken home) is presented for each grade. Model 3 adds the second predictor variable of interest—aggregated parental education. Model 4 adds the interaction between parental involvement and parental education. For significant interactive effects, Figures 1 through 6 present the percentage probability of substance use based on levels of parental involvement and parental education (each at .5, 1.0, and 1.5 standard deviations above and below the mean).

Table 4.

School-level parental involvement, parental education, and the interaction between parent involvement and education as predictors of the log-odds of students’ substance use

| Indices of Substance Use | Between-School Model Regression Coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 8th grade | |||||||

| Cigarette use in the past 30 days | −.169*** | −.060 | .019 | −.301** | .011 | −.153** | −.078* |

| Alcohol use in the past 30 days | −.087** | −.058* | −.028 | −.116 | −.031 | −.054 | −.045 |

| Heavy drinking | −.172*** | −.103*** | −.032 | −.274*** | −.035 | −.145*** | −.036 |

| Drunk in the past 30 days | −.142*** | −.090* | −.055 | −.134 | −.058 | −.065 | −.069 |

| Marijuana use in the past 30 days | −.197*** | −.041 | −.011 | −.109 | −.013 | −.056 | −.025 |

| Marijuana use in the past 12 months | −.187*** | −.058~ | −.028 | −.109 | −.029 | −.057 | −.016 |

| Illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months | −.080** | −.053 | −.014 | −.150* | −.016 | −.076~ | −.058* |

| 10th grade | |||||||

| Cigarette use in the past 30 days | −.058 | .028 | −.031 | .225** | −.027 | .256** | −.064 |

| Alcohol use in the past 30 days | .027 | .054~ | .007 | .174** | .007 | .172** | .005 |

| Heavy drinking | −.031 | .013 | −.022 | .132* | −.023 | .130* | .004 |

| Drunk in the past 30 days | .047 | .066~ | −.004 | .259*** | −.004 | .258*** | .002 |

| Marijuana use in the past 30 days | −.077* | .005 | −.071 | .287*** | −.073 | .275*** | .029 |

| Marijuana use in the past 12 months | −.067* | .001 | −.063 | .230*** | −.062 | .232*** | −.006 |

| Illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months | −.042 | .020 | −.005 | .097 | .001 | .115 | −.042 |

| 12th grade | |||||||

| Cigarette use in the past 30 days | .023 | .028 | .028 | .081 | .040 | .111 | −.063* |

| Alcohol use in the past 30 days | .132*** | .085* | .005 | .340*** | .010 | −.045 | −.022 |

| Heavy drinking | .106*** | .075 | .017 | .253*** | .029 | .274*** | −.052~ |

| Drunk in the past 30 days | .149*** | .114* | .022 | .313*** | .037 | .337*** | −.053 |

| Marijuana use in the past 30 days | .030 | .011 | −.022 | .171* | −.008 | .196*** | −.061* |

| Marijuana use in the past 12 months | .054 | .034 | −.010 | .201** | .008 | .236*** | −.085** |

| Illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months | .036 | .037 | .036 | .034 | .050 | .065 | −.067** |

p <.05,

p <.01,

p <.001

Note:

1 = Parental Involvement, 2 = Parental Education, and 3 = Interaction Between Parental Involvement and Parental Education.

Model 1 includes predictor variable parental involvement unadjusted to student and school demographic characteristics.

Model 2 includes predictor variable parental involvement adjusted to student and school demographic characteristics.

Model 3 includes predictor variables parental involvement and aggregated parental education.

Model 4 includes predictor variables parental involvement, aggregated parental education, and the interaction between parental involvement and aggregated parental education.

Regression coefficients in Models 2 through 4 are adjusted for school-level demographic characteristics—school size, type of school (public or private), and urbanicity (urban, suburban, or rural)—and student-level demographic characteristics—ethnicity (White, African-American, Hispanic, or Other), gender, parental education, broken home.

Figure 1.

Interaction between school-level parental involvement and aggregated parental education on the prevalence of cigarette use in the past 30 days among 8th-grade students.

Figure 6.

Interaction between school-level parental involvement and aggregated parental education on the prevalence of illicit drug use in the past 12 months among 12th-grade students.

Parental involvement predicting 8th-grade substance use

As shown in Table 4, parental involvement—unadjusted for school and student demographic characteristics (Model 1)—was significantly negatively predictive of all substance use indicators for 8th-grade students. The coefficients in Model 2 for all three indices of alcohol use—alcohol use in the past 30 days (γ = −.058, p < .043), heavy drinking in the past two weeks (γ = −.103, p < .002), and drunk in the past 30 days (γ = −.090, p < .001)—continued to be significant at 8th grade, even when adjusted for all student- and school-level controls except aggregated parental education; coefficients for other substance use measures became nonsignificant. When aggregated parental education was included in the equation (Model 3), parental involvement was no longer significantly predictive of alcohol use, and continued to be nonsignificant for the other substance use indicators. Aggregated parental education, however, was significantly negatively predictive of cigarette use in the past 30 days, heavy drinking, and illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months. In Model 4, which added the interaction between parental involvement and parental education, the main effect of parental involvement continued to be nonsignificant, and the main effect of parental education on 8th-grade students’ cigarette use and illicit drug use other than marijuana continued to be significant. There was also a significant negative effect of the interaction between parental education and involvement on these two indices of substance use behavior γ= −.08, p < .05 for cigarette use in the past 30 days; γ = −.06, p < .05 for illicit drug use in the past 12 months). Figure 1 presents the differences in overall prevalence of cigarettes among 8th-grade students in schools that range from lowest to highest along the two dimensions—parental involvement and aggregate parental education. As shown in Figure 1, the slope relating parental involvement to substance use is positive in schools with low parental education, but negative in schools with high parental education. Thus, for example, for schools with the highest aggregate parental education, schools with the lowest levels of parental involvement have 2.5% higher prevalence of cigarette use than schools with the highest levels of parental involvement. On the other hand, for schools with the lowest aggregate parental education, the prevalence of cigarette use is 4.5% higher in schools with the highest parental involvement compared to schools with the lowest levels of parental involvement. This suggests that, relative to schools with low aggregate parental education, 8th-grade students in schools with high aggregate parental education benefit from parental involvement in school-related activities. A similar conclusion can be drawn from Figure 2, which shows the pattern for use of an illicit drug other than marijuana.

Figure 2.

Interaction between school-level parental involvement and aggregated parental education on the prevalence of illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past 12 months among 8th-grade students.

Parental involvement predicting 10th- and 12th-grade substance use

In contrast to the unadjusted effect of parental involvement in 8th grade, parental involvement had little association with 10th-grade students’ substance use. There was a small though significant negative coefficient for parental involvement on the two indicators of marijuana use (Table 4, 10th grade), but none of the coefficients was significant when adjusted for school and student demographic characteristics. Aggregated parental education, however, was significantly and positively predictive of all indicators of alcohol and marijuana use among 10th-grade students (Table 4, Model 3 for 10th grade). There were no significant interactive effects of parental involvement and parental education on 10th-grade students’ substance use behavior.

Among 12th graders, parental involvement was significantly and positively associated with use of alcohol in the past 30 days (γ = .085, p < .005), heavy drinking in the past two weeks (γ = .075, p < .05), and getting drunk in the past 30 days (γ = .114, p < .05) (Table 4 for 12th grade). That is, relative to schools where administrators reported little parental involvement, in schools where administrators reported high levels of parental involvement, 12th-grade students were more likely to report using alcohol in the past 30 days, engaging in heavy drinking, and getting drunk in the past 30 days. However, when aggregated parental education was accounted for, parental involvement was no longer significantly predictive of 12th-grade students’ use of alcohol (Table 4, Model 3 for 12th grade). Thus, the hypothesized beneficial effect of parental involvement on students’ substance use behavior was not supported for 10th and 12th grades; but neither was the opposite relationship supported once aggregate parental education was taken into account.

Interestingly, and similar to results obtained for 8th graders, there was a significant negative interactive effect of parental involvement and parental education on 12th graders’ use of cigarettes in the past 30 days (γ= −.06, p < .05), marijuana use in the past 30 days (γ= −.06, p < .05), marijuana use in the past 12 months (γ = −.09, p < .01), and illicit drug use in the past year (γ= −.07, p < .01). These results are presented in Table 4, Model 4. Figures 3 through 6 present levels of overall prevalence of cigarette use, marijuana use in the past 30 days, marijuana use in the past 12 months, and illicit drug use in the past year among 12th-grade students ranging from lowest to highest in aggregate parental education and parental involvement. These figures present the predicted interactive effects of parental involvement and parental education (each at .5, 1.0, and 1.5 standard deviations above and below the mean) on the overall prevalence of substance use among 12th-grade students, controlling for school and student demographic characteristics. There was a 3.8%, 5.8%, 10%, and 2.5% drop in the prevalence of cigarette use, marijuana use in the past 30 days, marijuana use in the past 12 months, and illicit drug use in the past year, respectively, among 12th-grade students in the highest aggregate parental education schools with the highest levels of parental involvement. Parallel to findings for 8th graders, for the 12th-grade students, the prevalence of cigarette use, marijuana use in the past 30 days, marijuana use in the past 12 months, and illicit drug use in the past year increased by 8.2%, 4.1%, 8.3%, and 6.9%, respectively, in the lowest aggregate parental education schools with the highest levels of parental involvement. This again suggests that increased parental involvement in schools with higher aggregate levels of parental education substantially reduces 12th graders’ use of these substances, while increased parental involvement in schools with low aggregate levels of parental education is associated with higher levels of use.

Figure 3.

Interaction between school-level parental involvement and aggregated parental education on the prevalence of cigarette use in the past 30 days among 12th-grade students.

Discussion

In this study, parental involvement is conceptualized as a feature of the school social context. The focus is on the transformation of the school social environment as a consequence of the active engagement and involvement of parents. This construct is different from parents’ involvement in their child’s education and development at the individual level, which is the more common measure of parental involvement used in this field of research. This institutional-level measure of parental involvement is also distinct and different from data based on aggregating students’ reports of parental involvement to the school level; while the latter is based on students’ collective perceptions of their parents’ involvement in their education, the former is measured directly at the school level from the perspective of the school administrator.

Hill and Taylor (2004) emphasize the importance of studying parental involvement from diverse perspectives—school staff, parents, and children—because reports of parental involvement from these different sources are only moderately correlated, and each is related to student outcomes such as achievement. Most research in this field focuses on parents’ viewpoints, making this study’s examination of school administrators’ perceptions unique.

Consistent with earlier research (Eccles & Harold, 1996), reported levels of parental involvement are higher in 8th grade than in 10th and 12th grades. Our findings—that educated (and likely high-SES) parents tend to be more directly involved in their own children’s education, interact more often with school personnel, and participate more frequently in school-related activities—parallel findings in qualitative interviews with parents (Lareau, 1987, 1996) and survey data from adolescents (Desimone, 1999; McNeal, 1999) linking parental involvement in school with parental income.

The relationship between parental involvement in school-related activities and 8th and 12th graders’ use of cigarettes, marijuana, and illicit drugs varied as a function of overall level of parental education. Students in schools where most parents were college-educated benefited from increased levels of overall parental involvement. However, as the results indicate, this was not the case for students in schools where the overall level of parental education was low. Increased involvement in this case was linked to higher levels of cigarette, marijuana, and illicit drug use. Thus, even at comparable levels of involvement, schools with a less-educated parent body do not reap the advantages of high parental involvement. This is consistent with research reports based on individual-level data (McNeal, 1999).

The reasons for parental involvement may provide some explanation. That is, in interpreting these findings, we need to take into consideration the nature of parental involvement and whether it is proactive or reactive. In schools with high levels of parental education and involvement, parents may initiate the involvement. Research done at the student level affirms this explanation (Lareau, 1996). On the other hand, in schools where the parent body is less educated, parental involvement could be attributed to teachers and principals initiating the contact in an attempt to deal with student academic and behavioral problems. This explanation is consistent with research indicating that schools in impoverished communities are less likely to promote parental school involvement (Epstein & Dauber, 1991; Hill & Taylor, 2004) except to report behavioral problems (Kumar, Gheen, & Kaplan, 2002).

While we do not have data in the current study to examine reasons for involvement, comparisons among the various indices of involvement between schools with different levels of parental education are interesting. The percentage of parents meeting teachers was not very different among schools with overall high, middle, and low levels of parental education. However, in terms of volunteering and participating in other school activities, the differences were more marked, suggesting that interactions may be more proactive when parents are more educated and more reactive in schools with less educated parents. While beyond the scope of this paper, future research should explore the nature and reasons for involvement.

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

This study adds significantly to the literature on school-level parental involvement. First, the findings reported here are based on six years of data from 111,652 students in 1,011 schools across the nation. Second, this study is unique in that it focuses on school-level parental involvement and its effect on the student body as a whole. Third, the measure of overall parent involvement—the key variable in this study—has high reliability. Fourth, unlike much of the research on parental involvement, which focuses on elementary schools, this study examines the role of parental involvement in middle and high schools. Finally, instead of focusing on the effect of parental involvement on student achievement, this study examines the effect of parental involvement on adolescent substance use behavior. While substance use prevention programs often incorporate parent involvement, few (if any) studies have examined the effect of overall parental involvement in school-related activities on student substance use behavior.

A few words of caution are in order. In this study, the parental involvement measure was taken from the reports of school administrators. Therefore, there is only a single source of data from every school. Also, the measure of school-level parental involvement included only certain types of parent–school activities; many other forms of involvement, such as interactions with other parents or discussing a problem with the school principal, are not included. However, attending parent–teacher conferences and being active in parent–teacher organizations—the measures used in the present analyses—are good indicators of general parental involvement. Further, this study measures levels of involvement, but not the reasons behind involvement. It is essential to examine reasons for parental involvement in high- and low-SES schools. This, we believe, will shed more light on the interactive effects of parental education and school involvement on student substance use behavior.

Figure 4.

Interaction between school-level parental involvement and aggregated parental education on the prevalence of marijuana use in the past 30 days among 12th-grade students.

Figure 5.

Interaction between school-level parental involvement and aggregated parental education on the prevalence of marijuana use in the past 12 months among 12th-grade students.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (#032769), funding the Youth, Education, and Society study; and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (#DA01411), sponsoring the Monitoring the Future study. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsors.

Footnotes

All references to parental involvement refer to parental involvement at the school level unless otherwise indicated.

Contributor Information

Revathy Kumar, Email: revathy.kumar@utoledo.edu, Associate Professor, University of Toledo, and Adjunct Assistant Research Scientist, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, GH5000G, Mail Stop 921, 2810 W. Bancroft Street, Toledo, Ohio, 43606-3390, Phone# 419-530-2481, Fax # 419-530-8447.

Patrick M O’Malley, Email: pomalley@umich.edu, Research Professor, Survey Research Center, Institute for, Social Research, University of Michigan, 2320 ISR, 48109-1248.

Lloyd D. Johnston, Email: lloydj@umich.edu, Distinguished Senior Research Scientist, Institute for Social Research and Research, Professor, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2320 ISR, 48109-1248.

References

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith EE. The education–drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates/Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard WM. Parent involvement in elementary school and educational attainment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Battistich V, Schaps E, Watson M, Solomon D, Lewis C. Effect of the child development project on students’ drug use and other problem behaviors. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;21:75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Nomura C, Cohen P. A network of influences on adolescent drug involvement: Neighborhood, school, peer, and family. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1989;118:419–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RG, Zhang L, Johnson WD, Bender DR. Academic performance and substance use: Findings from a state survey of public high school students. The Journal of School Health. 2007;77:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Academic orientation and parental involvement in education during high school. Sociology of Education. 2001;74:210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone L. Linking parent involvement with student achievement: Do race and income matter? The Journal of Educational Research. 1999;93:11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryfoos JG. Adolescents at risk: Prevalence and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Harold RD. Family involvement in children’s and adolescents’ schooling. In: Booth A, Dunn JF, editors. Family-school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Eitle DJ, Eitle TM. School and country characteristics as predictors of school rates of drug, alcohol, and tobacco offenses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:408–421. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D, Sampson RJ, Elliot A, Rankin B. Effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33:389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL, Dauber SL. School programs and teacher practices of parent involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. Elementary School Journal. 1991;91:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL, Salinas KC. Partnering with families and communities. Educational Leadership. 2004;61:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL, Sanders MG. Prospects for change: Preparing educators for school, family, and community partnership. Peabody Journal of Education. 2006;81:81–120. [Google Scholar]

- Felner RB, Liska AE, South SJ, McNulty ML. The subculture of violence and delinquency: Individual vs. school context effects. Social Forces. 1994;73:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. Successful schools and competent students. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Green CL, Walker JMT, Hoover-Dempsey KV, Sandler HM. Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of parental involvement. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;99:532–544. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE, Davis-Kean PE, Eccles JS. Parents, peers, and problem behavior: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of relationship perceptions and characteristics on the development of adolescent problem behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:401–413. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson GD, Gottfredson DC, Payne AA, Gottfredson NC. School climate predictors of school disorder: Results from a national study of delinquency prevention in schools. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2005;42:412–444. [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hawkins D, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. A developmental analysis of sociodemographic, family and peer effects on adolescent illicit drug initiation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:838–845. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Broadening the vision of education: Schools as health promoting environments. Journal of School Health. 1990;60:178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1990.tb05433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance use prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes NM. Creating safe and caring school communities: Comer school development program schools. Journal of Negro Education. 1996;65:308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Hellman DA, Beaton S. The patterns of violence in urban public schools: The influence of school and community. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1986;23:102–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hess RD, Holloway SD. Family and school as educational institutions. In: Parke RD, editor. Review of child development research: Vol. 7. The family. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1984. pp. 179–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Taylor LC. Parental school involvement and children’s academic achievement: Pragmatics and issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover-Dempsey KV, Bassler OC, Brissie JS. Parent involvement: Contributions of teacher efficacy, school socioeconomic status, and other school characteristics. American Educational Research Journal. 1987;24:417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Successful adolescent development among youth in high-risk settings. American Psychologist. 1993;48:117–126. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006: Vol. I. Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 06–5883) Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft IG, de Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. London: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Gheen MH, Kaplan A. Goal structures in the learning environment and students’ disaffection from learning and schooling. In: Midgley C, editor. Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2002. pp. 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Association between physical environment of secondary schools and student problem behavior: A national study, 2000–2003. Environment and Behavior. 2008;40:455–486. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Effect of school-level norms on student substance use. Prevention Science. 2002;3:105–124. doi: 10.1023/a:1015431300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Turner CW. The social ecology model of adolescent substance abuse: Implications for prevention. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1990;25:435–463. doi: 10.3109/10826089009105124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. Social class differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital. Sociology of Education. 1987;60:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. Assessing parent involvement in schooling: A critical analysis. In: Booth A, Dunn JF, editors. Family-school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Bowen NK. Parent involvement, cultural capital, and the achievement gap among elementary school children. American Educational Research Journal. 2006;43:193–218. [Google Scholar]

- McNeal RB. Parental involvement as social capital: Differential effectiveness on science achievement, truancy, and dropping out. Social Forces. 1999;78:117–144. [Google Scholar]

- McWayne C, Hampton V, Fantuzzo J, Cohen HL, Sekino Y. A multivariate examination of parent involvement and the social and academic competencies of urban kindergarten children. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Felix-Ortiz M. Multiple protective and risk factors for drug use and abuse: Cross-sectional and prospective findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:280–296. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Kumar R. How substance use differs among American secondary schools. Prevention Science. 2006;7:409–420. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie J, Bunn F, Bryne G. Parenting programmes for preventing tobacco, alcohol, or drug misuse in children <18: A systematic review. Health Education Research. 2007;22:177–191. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong Y, Congdon R. HLM6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard J, Carlson JS. An empirical evaluation of school-based prevention programs that involve parents. Psychology in the Schools. 2003;40:641–656. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Chen R. Latent growth curve analysis of parent influences on drinking progression in early adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR. Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75:417–453. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development. 1992;63:1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson DL, Baker DP. The family-school relation and the child’s school performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1348–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui-Chu EH, Willms JD. Effects of parental involvement on eighth-grade achievement. Sociological Quarterly. 1996;69:126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HB, Mayer E, Kreider H, Vaughan M, Dearing E, Hencke R, Pinto K. Making it work: Low-income working mothers’ involvement in their children’s education. American Educational Research Journal. 2003;40:879–901. [Google Scholar]